Abstract

Im**ement jet heat transfer was studied using liquid and gas fluids to determine better cooling fluid. The materials used were rectangular steel plates of 230 mm by 120 mm by 12 mm, single jet diameters of 10–40 mm with im**ement gaps of 115–155 mm. A computational fluid dynamics software application ANSYS 2020R1 was employed for simulation, and lumped thermal mass analysis was used for experimental modeling. The experimental results showed an increase in heat transfer coefficient with increased pipe diameters and with a corresponding increase in im**ement gaps and flow rate. This revealed 265.4–383.9 W/m2 K and 85.3–109 W/m2 K at diameter 10 mm and 336.5–365 W/m2 K and 109.0–137.5 W/m2 K at diameter 40 mm for both water and air, respectively. Numerical simulation revealed heat flux of 22518–38.94 W/m2 and 7570.2–4.25 W/m2 and 6742.8–27.1 W/m2 and 4155.6–6.1 W/m at diameters 10 mm and 40 mm, respectively. This confirmed that water remains a better cooling fluid with a 6.2% difference at the diameter of 10 mm and a 0.1% difference at the diameter of 40 mm. An acceptable error margin of 4 to 18% upon the comparison of empirical analysis with numerical simulation is obtained. The above suggests a better cooling rate for the microstructure of the steel using water against air.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The jet im**ement cooling process is a heat removal process that enables the removal of heat from a hot surface faster. Over the years, with the continual enhancement of steel material functions, the growing demand for cost cutting by reducing the use of alloying elements, and streamlining processes: the thermomechanical control process (TMCP), has become increasingly important [1, 2]. At one point of the designer’s desired need, steel materials are subject to either of the following: bending and at the other to twisting, rotations, etc. Attending operations under these conditions requires certain specific properties to be able to successfully withstand the various conditions the designers subject them to [3]. Heat treatment, heating, and soaking at cooling temperature cycles steel are reduced, help before now to handle as much as possible, yet in recent times could not do more [4, 5]. Opined that by restructuring its microstructure and physical structure with proper monitoring and controlling of its temperature during heating and cooling processes. Its usage with the evolving engineering and technology advancement is due to the designer’s quest for newer applications, which causes the manipulation of steel’s mechanical and metallurgical properties to the designer’s desired design application. Therefore, there is a need for improving steel properties, which demand cost reduction in alloying elements, modeling, and streamlining processes, hence need for a better process [1]. In particular, the hot-rolling process, which is a well-known manufacturing method of steel strips, requires great management since it has a crucial influence on the properties of the final product [2].

Meanwhile, the modes of cooling by quenching process using different fluids opened it up for improvement. The era of controlled cooling opens up, an important part of thermomechanical controlled process (TMCP) technology, which significantly influences the microstructure and mechanical property of hot-rolled steel plates [6, 7]. As one of the important elements of this technology, the technique that allows the precise control of the fluid quenching temperature can be cited along with the metallurgical and controlled rolling techniques [1]. Therefore, jet im**ement cooling, a type of accelerated controlled cooling, is a process used to achieve high heat removal yield from a heated material using the desired coolant for easy cooling. Steel production having desired mechanical and metallurgical properties requires accurate temperature control during the cooling process as noted by [8]. This work looks for a solution to the Leidenfrost phenomenon in water from another fluid.

Steel as an engineering material

Agreeing to the Society of Automobile Engineers and the American Institute of Steel, iron and steel are alloys of iron and carbon that normally have less than 1.0wt% of carbon [9]. It may contain other alloying elements at different compositions and/or heat treatment [10,11,12]. In this present work, we recognized three main grades of steel: low, medium, and high carbon steel with carbon content ranges of 0.015–0.30%wt for low carbon steel, 0.031–0.58%wt for medium carbon steel, and 0.6–2%wt for high carbon steel [13].

Hydrodynamics of jet im**ement

Jet from the ROT cooling stage first exits the circular nozzle and im**es over the dry heated plate surface (free-surface jet), followed next by arrays that collide with the leftover fluid on the surface (plunging jet). These two types are mostly treated as free-surface jets in comparison with the submerged jet. Accordingly, [14] showed some types of single jet im**ement cooling. This work uses a free-surface jet im**ement cooling profile as shown in Fig. 1 below.

Schematic of free-surface jet and liquid velocity profile parallel to surface circular jets [15]

The flow of the liquid in im**ement process can be divided arbitrarily into two zones, the im**ement zone characterized by a sharp increase in the streamwise velocity and a parallel flow zone with a more gradual change of streamwise. Figure 1 depicts the streamwise velocity (ui). In hydrodynamics, the streamwise at the stagnation point increase to the jet streamwise velocity Vji. The hydrodynamics of circular jets differ from others in the parallel flow region. This is because the water velocity in the parallel flow zone of circular jets decreases, whereas the water velocity for the planar jet does not decrease [16].

Computational fluid dynamics

Numerical solution based on computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is the analysis of systems involving fluid flow, heat transfer, and associated phenomena such as chemical reactions using computer-based simulation; this technique is very powerful and spans a wide range of industrial and nonindustrial application areas [17]. CFD is an effective and powerful tool to numerically simulate fluid flow and heat transfer. The conventional methods which are the most popular in CFD are the finite element method (FEM), finite volume method (FVM), finite difference method (FDM), and spectral methods. These methods solve nonlinear Navier-Stokes equations which are governing equations for CFD describing popular conservation of mass, momentum, and energy equations [18]. The baseline results from CFD analysis are compared with experimental analysis, using ANSYS FLUENT and many other fluid flow software as studied by [2, 9, 19].

Many numerical models have been studied like SST k-w model while v2f turbulence model for turbulence analysis because of its minimal error at the stagnation point and wall regions. Numerically, revealing that the ratio of the nozzle diameter to cylinder diameter affects Reynolds number value also showed that the RNG k-e model is better in predicting heat transfer characteristics. We found also that inlet turbulent intensity and eddy viscosity ratio are vital for the accurate prediction of realistic results using various RANS turbulence models; all these models are for fluid flow characteristics onto the hot surface as studied by [20,21,22,23]. Nur et al. [24] studied hybrid nanofluid using single jet im**ement cooling, and they showed that its heat transfer performance is highest and reduces the greatest amount of heat from the surface to the fluid. The models reviewed above are for the fluid and heated surface interaction. This work presents the knowledge in the behavior of the hot steel plate heat dissipation only. This has been uncertain in the literature for the single jet im**ement cooling process. In the literature, it has been empirical analysis with minimal or no validation. Hence, this work assessed the behavior of controlled cooling of a hot-rolled steel plate using liquid and gas single jet im**ement cooling by the transient thermal model of ANSYS fluent 2020R1.

Methods

The schematic of the modified run-out table system set-up plant is used and hoses the combined liquid and gas lines in the same headers. The location of these parts is shown on the schematic diagram in Fig. 2.

Schematics of the modified ROT set-up plant: 1, water tank; 2, electric pump; 3, heater; 4, thermocouple wires; 5, the workpiece and its carrier; 6, thermocouple control panel, workpiece bed; 7, bottom im**ement nozzle; 8, motorized screw conveyor; 9, furnace; 10, electric motor; 11, flow valve/air attachment nozzle; 12, flow meter; 13, ladder; 14, furnace support; 15, PVC pipes; 16, pressure gauge, 17

Experimental procedure

Based on im**ement diameters, D = 10 mm and 40 mm with corresponding varying im**ement gaps H, of 115 and 155 mm at two different controlled cooling temperatures of 150 °C and 110 °C, respectively. The experiments carried out were with a modified test rig, in Fig. 2. The assessment and numerical simulations were done using lumped thermal mass analysis, used to generate various values of heat transfer coefficient (h), and ANSYS was employed for simulation and 3-D modeling of the transient thermal model of the steel plate — 230 mm length by 120 mm width by 12 mm thickness, for temperature time and heat flux. The following test parameters based on Fig. 2 were used as experimental indicators: flow rate, nozzle velocity, constant im**ement diameters, varying im**ement gaps, surface temperatures, and controlled temperatures, cooling time, and rate.

The air jet im**ement experiment was done using the same rig that has an air attachment nozzle at the flow valve close to the headers, with an air compressor machine producing and supplying the air. Table 1 shows the properties of the sampled im**ement fluids — liquid and gas (water and air).

Medium carbon steel plates with known varying chemical compositions and mechanical properties were obtained from the Ajaokuta Nigerian Steel Company with a steel grade of 0.56%C, the ultimate tensile strength of 957.1 Mpa, and Brinell hardness of 252.98 having an impact strength of 34.11 J.

Data analysis

This model of the im**ement process is centered on the demonstration of transient-state heat conduction-convection across the sampled workpiece thickness of 12 mm, length of 230 mm, and width of 120 mm dimensions (Fig. 3).

Integration from t = 0 to T = Ts:

where α becomes the following:

The gradient is Eq. 4 given as in Eq. 5, as follows:

where h is heat transfer coefficient W/m2 k

\(for\ steel, density\kern0.5em \rho =\frac{7900 hg}{m^3},\kern0.5em specific\ heat\ Cp=\frac{500J}{kgk}, sampled\ thickness\ w=0.012m\), and ∝ is a gradient from Eq. (5)

Thereafter, a spread Excel sheet was used to estimate h Eq. (6), where h =∝ρwc, for ∝ being the slope based on lumped numerical experimental temperature-time plots. These values of convective heat transfer coefficient h were calculated.

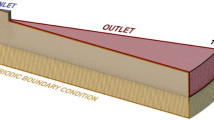

Numerical simulation model

The simulation model is as shown in Fig. 4a which represents the hot steel plate 230 × 120 × 12 mm dimensions. The inlet nozzle diameters are 10 and 40 mm, while the im**ement gaps are 115 and 155 mm. The mesh structure used in the study is in Fig. 4b. This study demonstrated a simple three-dimensional geometry simulation. The type of fluids used in the simulation is liquid and gas coolant with ANSYS transient thermal model for simulation.

Grid independence

To determine the ideal number of grids used and the impact of the number of elements on heat transfer and the final temperature of the target surface, the mesh was analyzed. A coarse mesh with 552 number of elements and 0.02 m cell size employed in this study. Figure 5 shows the result of the grid independence test; additionally, patch conforming method and inflation method are applied to the geometry to ensure the flow of fluid near the target surface is well defined.

Boundary conditions

The boundary condition for the inlet velocity is determined based on the calculated Reynolds number. The inlet temperature and the surface temperature of the plate are set at 323 and in the range of 683 to 723 k for diameters of 10 mm and 40 mm, respectively. The temperature is set according to the working temperature of a microchip cooling system, which utilizes the fluid jet im**ement cooling method of Nur et al. [24].

The final subcooled temperature was predetermined by the design in the range of 150 to 110 °C, and the heat transfer coefficient was calculated using LTMA and was inputted to ANSYS; thus, the wall heat flux was determined by the post-processing stage.

The Reynolds number used as the input parameter is in the range of 5000 to 250,000. The pressure treatment adopted the first-order upwind scheme for the turbulence numeric and the adventive scheme. While for the viscous model, a standard k-epsilon model was selected. The simulation was defined as converged at an RMS value lower than 1.0E−4. The results of the simulation are calculated throughout the computational domain during the simulation process.

Results and discussion

Experimental temperature-time evaluation

For controlled cooled temperature of 150 °C, diameter D = 10 mm. Results are presented in Tables 2 and 3, used for generating Fig. 6 and Tables 4 and 5 for Fig. 7 at D = 40 mm and controlled cooling temperature of 110 °C that corresponds to W-JIC and A-JIC, respectively.

From all the graphs above, irrespective of the controlled cooled temperatures, the initial surface temperatures of hot-rolled steel plates showed the highest cooling time at a gap of 115 mm and lowest at a gap of 155 mm in each of the constant im**ement diameters. This agrees with Onah, and Farial [25, 26] showing the same linear decrease.

Evaluated heat transfer coefficients (h) from LTMA

The results of the experiment for temperature time were then further analyzed by lumped thermal mass analysis which showed a linear decrease from various surface temperatures to various cooling times of the form y = − ∝ x + a for R2 = b, where ∝ is the slope used for estimation of various convective heat transfer coefficient h from Eq. (5).

Ln (theta) for diameter D = 10 mm controlled at temperature of 150 °C is presented in Tables 6, for W-JIC and A-JIC used to generate Fig. 8, while Table 7 for W-JIC and A-JIC at diameter 40 mm is for Fig. 9 at different im**ement gaps of 115 and 155 mm, respectively.

However, in all the controlled temperatures, the values of the slope of lumped thermal mass analysis∝, in ln(theta) temperature against time for determining convective heat transfer coefficient (h), indicated a linear increase in im**ement diameter D and a corresponding increase in im**ement gap H. This is suggestive that the various values of convective heat transfer coefficient (h) as obtained would be more at higher diameter D and higher im**ement gap H, for proficient steel cooling, as studied by [27,28,29].

Heat transfer coefficient h from LTMA

Results of heat transfer coefficient (h) for D = 10 mm are presented in Table 8.

At constant diameter D = 10 mm, the convective heat transfer coefficient “h” showed an increase with increasing im**ement gaps. Water has the highest values at both diameters and gaps. Flow rate decreased with increasing im**ement gaps. The water decreased from 1.625 × 10−3 m3/s to 4.9 × 10−4 m3/s, and air decreased from 3.67 × 10−3 m3/s to 4.43 × 10−4 m3/s. This inferred that the lower the im**ement gap H, the higher the flow rate Q.

For constant diameter D = 40 mm, convective heat transfer coefficient “h” maintained the same pattern, with water still having the highest.

This infers that at any given constant pipe diameter (D), flow rate (Q) decreases with a corresponding increase in im**ement gap (H), resulting in increased convective heat transfer coefficient (h). This will give a proficient higher heat extraction rate on hot-rolled steel plates cooling in the steel mill industry and achieve designer desired microstructures of steel, as also studied by [27,28,29].

Study of numerical simulation results

Figures 10 and 11 describe the CFD temperature-time controlled cooling model — region 1, is blue and totally cooled layer; region 2, is yellow, the middle layer, and partially cooled; and region 3, is red bottomed layer, gradually cooled, but still hotter than the two layers, Also, it indicates the temperature-time plot of the model, at each of the regions. The steeper curve region 1 showed where the convective heat transfer coefficient h was applied and slowly goes down to region 2 and to region 3, where heat flow was perfectly insulated that retained some hotness in the steel plate. Figures 12 and 13 represent the CFD-controlled heat flux model, where the top region showed the highest heat flux down to the bottom the lowest. Again, it also showed a plot of the heat flux against time. The rate of heat flux dissipation was 2.2 × 10−6 W/m2/s and 1.74 × 10−7 W/m2/s maximum for W-JIC and A-JIC, respectively.

Figures 14 and 15 describe the CFD temperature-time controlled cooling model, showing the same pattern as D = 10 mm, and CFD temperature-time plot, at each of the regions, having the same shape as the plot of D = 10 mm. Figures 16 and 17 represent the controlled heat flux model. It showed the same pattern of cooling as above, as well as showing a plot of the heat flux against time. The rate of heat flux dissipation was 1.10 × 10−7W/m2/s and 1.33 × 10−7W/m2/s maximum for W-JIC and A-JIC, respectively, which suggested water as a better im**ement fluid as opined by [8, 26]. This dissipation of heat flux showed that water removes heat per unit area per second better than air in both diameters.

Table 9 showed the heat fluxes at D = 10 mm and 40 mm, highest at the top where the convective heat transfer coefficient value is more. Heat flux showed a 66.4% difference for D = 10 mm and 75.2 for D = 40 mm for W-JIC and A-JIC, respectively. Furthermore, heat fluxes decreased linearly from top to bottom, showing an increase in convective heat transfer coefficient with corresponding increasing im**ement gap H.

Experimental and CFD numerical simulation temperature-time profile validation

Experimental and simulated data of both diameters are presented in Table 10 at convective heat transfer coefficient of h for water and h for air.

Table 10 showed the controlled temperature of 150 °C and 110 °C and initial temperature T = 450 °C and 410 °C for varied time t(s) for both experimental data and the ANSYS CFD simulation data plotted in Fig. 18 for both diameters. An acceptable error margin is of 4.5–6.6%. Confirming the affirmation, that water is a better fluid as specified by Md Lokman and Onah [25, 30].

Experimental uncertainties concomitant

The concomitant uncertainties in this work are the vital influences or limitations that are very expedient in the attainment of the set goal in this work, which is very grim to regulate. Thus, the plus or minus estimation uncertainties are ways of checkmating the errors in the measurement of these influences. These influences are underscored in Table 11.

Uncertainties for random measurement

Random uncertainties with absolute temperature values are as follows: for D = 10 mm, H = 115 mm at 150 °C, and for water T = (450 + 440 + 430 + 420 + 410)/5 = 430 °C. Meanwhile, the spread of temperature measurement ΔT is 0.9 °C; thus, T = 430 ± 0.9 °C. Conversely, pressure random uncertainties were determined as follows: for D = 10 mm, H = 115 mm at 150 °C is (2.5 × 105 + 2.5 × 105 +2.5 × 105 + 2.5 × 105 + 2.5 × 105)/5 = 2.5 × 105 N/m2, and equally the spread of pressure measurement ΔP is 0.1 × 105 N/m2; thus, P = 2.5 × 105 ± 0.1 × 105 N/m2.

Uncertainties for random measurement

The water flow meter used has a specification of an accuracy: ± 1% of reading uncertainty tolerance; in addition, the water pump used has a current of 2.5 amp and a capacity of 0.5 hp. The pressure gauge calibrated was in the range of 0 to 10 bars with a measurement uncertainty tolerance of ± 0.1. In the testing and installation of the thermocouple, it recorded 97 °C with an error of ± 0.26 °C. The volumetric measuring cylinder calibrated was in the range of 50 to 500 mm3 with ± 0.1 mm3 uncertainty error. Similarly, the stopwatch calibrated was in the range of 0 to 60 s and at the top end with an accuracy uncertainty of ± 0.1.

Uncertainties for reduction measurement

For temperature, the uncertainty is for D = 10 mm, H = 115 mm at150 °C for water, and T = 430 °C, since the uncertainty in measure ΔT is 0.9 °C; thus, T = 430 ± 0.9 °C, and then, reduction temperature uncertainty is (0.9/430) × 100 = 21%. In the pressure reduction uncertainty, D = 10 mm, H = 115 mm at150 °C, and P = (2.5 × 105 N/m2). The associated uncertainty measurement ΔP is 0.1 × 105 N/m2; thus, P = (2.5 × 105 ± 0.1 × 105 N/m2), and then, reduction pressure uncertainty is (0.1 × 105/2.5 × 105) × 100 = 40%.

Conclusions

This study involved a comparative study of jet im**ement fluids. Empirical results using lumped thermal mass analysis revealed convective heat transfer of 265–365 W/m2 K and 85–138 W/m2 K for W-JIC and A-JIC, respectively at diameters of 10 mm and 40 mm. CFD numerical simulation revealed maximum heat fluxes of 22518 W/m2 and 6742.8 W/m2 for water and 7570.2 W/m2 and 4155.6 W/m2 for air at 10 mm and 40 mm, respectively. This confirmed water as the best im**ement cooling fluid with a 6.2% difference at a diameter of 10 mm and a 0.1% difference at a diameter of 40 mm. validation of empirical results with numerical simulation results showed an acceptable error margin of 4 to 18% for diameters 10 mm and 40 mm, respectively. Certainly, with Kandilkar [31] study, this further confirms results in the literature that water will give a proficient higher heat extraction rate on hot-rolled steel plates in the steel mill industry.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included in the article.

Abbreviations

- A-JIC:

-

Air jet im**ement cooling

- ANSYS:

-

Analytical system

- A:

-

Area (m2)

- CFD:

-

Computational fluid dynamics

- Cp:

-

Specific heat capacity (J/kg k)

- D:

-

Diameter (mm)

- ESUT:

-

Enugu State University of Science and Technology

- h:

-

Heat transfer coefficient (w/m2 k)

- H:

-

Im**ement gap (mm)

- FEM:

-

Finite element method

- FVM:

-

Finite volume method

- FDM:

-

Finite difference method

- LTMA:

-

Lumped thermal mass analysis

- M:

-

Mass (kg)

- MME:

-

Metallurgical and material engineering

- PVC:

-

Polyvinyl chloride

- P:

-

Pressure (N/m2)

- Q:

-

Flow rate (m3/s)

- ROT:

-

Run-out table

- RMS:

-

Root mean square

- T:

-

Initial temperature (°C)

- Tsub :

-

Subcooled temperature (°C)

- T∞:

-

Infinite temperature (°C)

- TMCP:

-

Thermomechanical cooling process

- t:

-

Time (s)

- ui :

-

Streamwise velocity (m/s)

- vij :

-

Streamwise jet velocity (m/s)

- W-JIC:

-

Water jet im**ement cooling

- w:

-

Thickness (m)

- ΔT:

-

Change in temperature (°C)

- ΔP:

-

Change in pressure (N/m2)

- Ρ:

-

Density (kg/m3)

References

Kazuaki K, Osamu N, Yoichi H (2016) Water Quenching CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) Simulation with Cylinderical Im**ing Jets. In: NIPPON Stell and SUMITOMO Metal Technical Report. Tiabah University of Saudi Arabia, Scholl of Post Graduate studies, Osaka

Alqash SI (2015) Numerical Simulations of Hydrodynamics of multiple water jet im**ing over a horizontal moving plate. In: Numerical Simulations of Hydrodynamics of multiple water jet im**ing over a horizontal moving plate. University of British Columbia, Vancouver; p 125.

Anthonio AG, da Silveira JHD (2014) Accelerated Cooling of Steel Plates: The Time has Come. J ASTM Int 5:8–15

Purna (2013) Model Based Numerical State Feedback Control of Jet Im**ement Cooling of a Steel Plate by Pole Placement Technique. Int J Comput Eng Res 03(8):2205–3005

Yongjun Z (2015) The Cooling of a Hot Steel Plate by Im**ing Water Jet. Wollongong university, Australia

**ed Jets. ISIJ Int 5(8):1-7

Ade (2011) Effect of Heat Treatment on the Mechanical Engineering Essay. In: 1st International Conference on Experiments/process/system Modelling/Simulation/Optimization Intelligence. Tiabah University of Saudi Arabia, Scholl of Post Graduate studies, London

Molana (2013) Investigation of Heat Processes Onvolved in Liquid Im**ement Jets: A Review. Braz J Chem Eng 03(30):413–435

Webb, Ma (2015) Single-Phase Liquid Jet Im**ement Heat Transfer. J Acad Press Im**ement Heat Transfer 26(126):105–115

Moukalled F, Managani LA (2016) Finite Volume Method in Computational Fluid Dynamics, Advanced Introduction with OpenFOAM and Matlab. Springer International, Switzerland

Ujam AJ, Onah T, Chime TO (2012) Effect of heat flow rate Q on convective heat transfer H, of fluid jet im**ement cooling on hot plate. Int J Industr Eng A Technol 2(2):16–30

Ujam AJ, Onah T (2013) Effect of Jet Reynold’s Number on Nusselt Number for Convective Im**ement Air Cooling on a Hot Plate. J Energy Technol Policy 3:10

Ujam A, Ojobor SN, Onah TO (2012) Effect of coolant mass flow rate G on coefficient of convective heat transfer, H on a hot plate. WEEJS Int J Arts Combined Sci 3:1

Incorpera (2015) Advances in Heat Transfer. Academic press, Massachusetts

Rahman SM, Simanto MdH (2016) Effect of heat treatment on low carbon steel: An experimental Investigation; International Conference on materials and amnufacturing Engineering, Applied mechanics and materials 860(7). https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.860.7.

M. John (2011) https://www.efunda.com/materilas/material_home/materilas.cfm

Jeffery A (2011) Advanced Engineering Mathematics. Academic press, Massachusetts

Verteeg et al (2017) An Introduction to Computational Fluid Dynamics: The Finite Element Method. Pearson Education Publishing, Edinburgh

Autulkumar K, Singh D (2019) Comparison of Various RANS models for im**ing Round Jet Cooling from a cylinder. ASME J Heat Transfer 141(6):064503

Khurmi, Sedha (2012) Theory of Metal on Carbon Steels and Mechanical Properties of Medium Carbon Steel

Gilles GG, Vladan PA (2019) Modeling of Transient Bottom Jet Im**ement Boiling. Elesevier Int J Heat Mass Transfer 136:1160–1170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2019.03.060.

Onah TO, Ekwueme BN, Odukwe A, Nduka NB, Orga AC, Egwuagu MO, Chukwu**du S, Diyoke C, Nwankwo AM, Asogwa CT, Aka CC, Enebeh K, Asadu C (2022) Improved design and comparative evaluation of controlled water jet im**ement cooling system for hot roll steel plates. Elseiver Int J Thermofluids 15:100172

Md Lokman, H. A., “Literature Review of Accelerated CFD Simulation Methods towards Online Application,” The 7th International Conference on Applied Energy , Elsevier Energy Procedia, 75, pp. 3307-3314, 2015.

Dushyant S, Premachandran B, Sangeeta K (2013) Numerical Simulation of the Jet Im**ement Cooling of a Circular Cylinder. Taylor and Francis Numerical Heat Transfer J Comput Method 64:2

Joseph I, Dushyant S, Saurabh K (2019) Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Heat Transfer Charateristics of Jet Im**ement on a Flat Plate. Springer J Heat Mass Transfer 56:531–546

Kandlikar SABA (2007) Evaluation of Jet Im**ement Spray and Microchannel Chip Cooling Options for High Heat Flux Removal. Heat Transfer Eng 28(11):911–923

Nur SM, Hanaf WA, Ghopa W, Zulkifli R, Abdullah S, Harun Z, Mansor MRA (2022) Numerical simulation on the effectiveness of hybrid nanofluid in jet. In: TMREES22-Fr, EURACA, 09 to 11 May 2022, Metz-Grand Est, France. Metz-Grand Est

Cemil Y, Nedim S, Yao SC, Hasan Riza GA (2011) Experimental Measurement and Computational Modeling for the Spray Cooling of a Steel Plate Near the Leidenfrost Temperature. J Thermal Sci Technol 31:27–36

Pallavi CC, Ashish NS (2017) Experimental and CFD Analysis of Jet Im**ement Cooling on Copper Circular Plate. World J Eng Res Technol III(5):256–267

Callister, Phase Transformation of Microstrutural Formation from Austenite, 2012.

Farial (2012) Flow Visualization and heat transfer characteristic of liquid jet im**ement. Int J Comput Method Eng Mech 13(4):239–253

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AN wrote up the manuscript. TO and AN conducted the laboratory experiments. BN supervised the laboratory experiment and structured, edited, read, and approved the final manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

AN is currently a lecturer, at the Department of Mechanical Engineering Caritas, Enugu. TO is a lecturer, Department of Mechanical and Production Engineering, Enugu State University of Science and Technology, Enugu state. BN is currently a Professor of Mechanical Engineering, at Michael Okpara University of Agriculture Umudike, Abia state.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nwankwo, A.M., Onah, T.O. & Nwankwojike, B.N. Assessment of liquid and gas im**ement cooling fluids with numerical solution for better steel austempering. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 69, 88 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s44147-022-00139-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s44147-022-00139-8