Abstract

Background

Despite the widespread use of antenatal care (ANC), its effectiveness in low-resource settings remains unclear. In this study, self-reported health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was used as an alternative to other maternal health measures previously used to measure the effectiveness of antenatal care.

The main objective of this study was to determine whether adequate antenatal care utilization is positively associated with women’s HRQoL. Furthermore, the associations between the HRQoL during the first year (1–13 months) after delivery and socio-economic and demographic factors were explored in Rwanda.

Methods

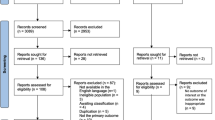

In 2014, we performed a cross-sectional population-based survey involving 922 women who gave birth 1–13 months prior to the data collection. The study population was randomly selected from two provinces in Rwanda, and a structured questionnaire was used.

HRQoL was measured using the EQ-5D-3L and a visual analogue scale (VAS). The average HRQoL scores were computed by demographic and socio-economic characteristics. The effect of adequate antenatal care utilization on HRQoL was tested by performing two multivariable linear regression models with the EQ-5D and EQ-VAS scores as the outcomes and ANC utilization and socio-economic and demographic variables as the predictors.

Results

Adequate ANC utilization affected women’s HRQoL when the outcome was measured using the EQ-VAS. Social support and living in a wealthy household were associated with a better HRQoL using both the EQ-VAS and EQ-5D. Cohabitating, and single/unmarried women exhibited significantly lower HRQoL scores than did married women in the EQ-VAS model, and women living in urban areas exhibited lower HRQoL scores than women living in rural areas in the ED-5D model. The effect of education on HRQoL was statistically significant using the EQ-VAS but was inconsistent across the educational categories. The women’s age and the age of their last child were not associated with their HRQoL.

Conclusions

ANC attendance of at least four visits should be further promoted and used in low-income settings. Strategies to improve families’ socio-economic conditions and promote social networks among women, particularly women at the reproductive age, are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Maternal mortality remains a principal measure of maternal health despite the widespread recognition that the maternal death rate is only a single indicator of ill maternal health [1, 2]. Recent studies have quantified problems, such as mental distress, genital infections, breast problems [3, 4], physical complaints, pain, sleep problems [4], urinary incontinence, and anemia [5], occurring during the postpartum period. However, the available data do not fully describe maternal health according to the definition of health as “physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” [6]. Women’s health-related quality of life (HRQoL) during the postpartum period is affected by their living conditions [7,8,9,10,11,12], reproductive history [7, 13, 14], and exposure to and use of reproductive health and antenatal care services [5, 15]. Maternal complications can have long-lasting consequences that impact the lives of women and their families for a long period [16].

The umbrella term antenatal care describes medical and social practices performed during pregnancy [17]. Despite the widespread use of antenatal care, its effectiveness in low-resource settings remains unclear [18, 19]. According to various observational studies, antenatal care has positive effects, such as lower maternal and perinatal mortality and better pregnancy outcomes [20]. Evidence of the effectiveness of antenatal care is necessary for decision-makers to establish adequate policies and strategies and allocate proper resources for their implementation. The self-reported HRQoL is an appropriate outcome measure in evaluations of maternal health interventions because this measure is often used in health economic evaluations [21] and can capture health events that are rarely fatal [22].

In this study, we used data obtained from a cross-sectional population-based survey in Rwanda to investigate women’s HRQoL during the first year after delivery. Our main objective was to determine whether adequate antenatal care utilization, which is a binary variable defined according to the number of visits and timing of the first visit, is positively associated with women’s HRQoL. Furthermore, we explored the association between HRQoL and socio-economic and demographic factors. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first investigation of women’s self-reported HRQoL after delivery in Rwanda. Our study contributes to the literature regarding the burden of maternal morbidity and, ultimately, to governmental health and social policies designed to improve women’s well-being.

Methods

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional population-based survey involved women who gave birth between 1 and 13 months prior to the data collection.

The study population was randomly selected from all districts in Kigali City and the Northern Province. Kigali City has three districts, and the Northern Province has five districts. Kigali City has a population of 1,135,428, and most residents live in areas with urban characteristics (i.e., housing, economic activities, and access to infrastructures), while the Northern Province has 1,729,927 inhabitants living mainly in rural areas [23]. The total population in the selected provinces represents 27.2% of the country’s total population [23]. Kigali City and the Northern Province were chosen not only because of logistical reasons but also because these areas are considered to reflect the situation in other provinces based on various surveys conducted in Rwanda showing no major regional differences in the reproductive health indicators [24].

Participant selection

The sample size was calculated based on the estimated prevalence of hypertension as a pregnancy complication (p = 10%) [25], a precision rate of 5%, and projected non-response rates of 10 and 5% to account for the design effect.

Three-stage sampling was conducted to identify the households to include in the study. First, in eight districts (three in Kigali City and five in Northern Province), 48 primary sampling units, i.e., villages, which represent the lowest administrative unit in Rwanda, were randomly selected from a total of 3918 villages in the two provinces, corresponding to 1.2% of the total number of villages [26]. Twenty percent of the villages were selected from urban areas, and 80% of the villages were selected from rural areas to reflect the rural-urban proportions in Rwanda. Second, the number of households selected in each village was decided according to the proportion to the total number of households in each village. In each village in Rwanda, community health workers maintain records of women expecting to deliver and women with newborns and infants less than 1 year of age. Third, these records were used to randomly select the households to be visited, and the list was reduced to only include households with a woman who fulfilled the main inclusion criterion, i.e., delivery within 1 to 13 months before the survey.

If a village did not have the desired number of households fulfilling the inclusion criterion, the remaining households were selected from a neighboring village. In total, 922 women were selected and invited to participate. All women agreed to participate.

Data collection procedure

A questionnaire comprising socio-economic and demographic factors, health conditions, and the use of maternal health services was developed in English and translated into Kinyarwanda by a professional translator with experience in translating medical and public health questionnaires in Rwanda.

The data collection was performed by the University of Rwanda, School of Public Health between July and August of 2014. In addition to four PhD students who were responsible for leading the fieldwork and their five supervisors, 12 female data collectors were hired. The data collectors had previous training in nursing or a related subject (minimum of 6 years of post-primary school) and experience in population-based data collection. The data collectors received a 4-day training, including 1 day of piloting in one village (not included in the sampled area). Data entry was performed by four experienced data clerks trained on using an SPSS data-entry template (SPSS version 22.0) [27] and supervised by a data manager.

Measures

Dependent variable

The dependent variable is the HRQoL, which was measured according to the EQ-5D praxis. The following two methods [28] were used:

(1) The EQ-5D-3L descriptive system (designated EQ-5D) comprises the following five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression. The respondents selected among three options (i.e., no problems, some problems, severe problems) in response to each dimension. Each response provides a combination (e.g., 1, 1, 2, 1, and 2) that has a corresponding value, often called a score [28]. Given the lack of an official version of the EQ-5D-3L in any language spoken in Rwanda, we translated the English version of the EQ-5D-3L into Kinyarwanda and obtained retrospective permission to use the translated questionnaire from EuroQol. To calculate the EQ-5D scores, we used the weights used in a population study conducted in the UK [29].

(2) Using the visual analogue scale (designated EQ-VAS), the women were asked to express how good or poor their health was on the day of the interview by indicating a point on a scale from 0 to 100. A score of 100 represented the best imaginable health state, while a score of 0 represented the worst imaginable health state.

Independent variables

The main independent variable was adequacy of antenatal care utilization, which is a binary indicator of whether a woman had received antenatal care according to Rwandan guidelines. This variable was constructed using Kessner’s index [30] as a prototype and adapted to the Rwandan antenatal care guidelines. The Rwandan antenatal care policy was developed based on the 2002 WHO guidelines, which suggested four focused antenatal visits for normal pregnancies [31]. However, most Rwandan couples do not adhere to this recommendation. For example, in 2014/15, only 45% of women completed four visits, and the average month of initiation of the first antenatal visit was the fifth month of gestation [24]. The following two categories of this variable were constructed:

-

(1)

The women were categorized as having adequate antenatal care (ANC) utilization if they had completed at least four ANC visits and the first visit occurred during the first trimester.

-

(2)

The women who did not meet the abovementioned criterion were categorized as having inadequate ANC utilization.

The women’s socio-economic and demographic characteristics were divided into the following groups: residence was divided into two groups (i.e., rural and urban) according to the location of the village; age was divided into groups in 5-year intervals; educational level was divided into four groups (i.e., some primary school, completed primary school, lower secondary or vocational education, and upper secondary or higher education); and marital status was divided into four groups (i.e., married, cohabitating, separated/divorced/widowed, and unmarried/single).

A household wealth index was constructed by performing principal component analysis and using information regarding housing characteristics (i.e., materials used to construct walls, source of water, type of cooking fuel, and connection to electricity) and ownership of durable assets (i.e., mattress, iron, TV, mobile phone, and computer). The household scores were standardized based on a normal distribution with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one [32]. The households were ranked according to these scores and divided into the following five equal groups: lowest, second, middle, fourth, and highest wealth quintiles.

The social support variable was constructed from seven questions regarding the respondents’ access to four main types of social support, i.e., emotional, tangible, or instrumental, informational and appraisal support, which are often referenced in the medical literature [33, 34]. The responses were dichotomized, given the values 0 (never) or 1 (sometimes, often or always) and summed for all respondents. Thus, the respondents were assigned social support values ranging between zero and seven. Finally, the values were grouped into the following two categories: poor social support (access to 0–4 types of social support) and good social support (access to 5–7 types of social support).

Statistical analysis

The average EQ-5D scores and 95% confidence intervals were calculated in relation to all independent variables. First, a bivariate analysis was performed using independent t-tests and one-way analyses of variance to identify the significant differences in the mean HRQoL values among different groups of independent variables at a 0.05 significance level. Second, two multivariable linear regression models were constructed using the EQ-5D scores and EQ-VAS scores as the outcomes and the adequacy of ANC utilization and socio-economic and demographic variables as the predictors. All predictors included in the bivariate analysis were considered in the initial model, except for the variable “Number of children” because this variable had a high proportion of missing values (31.4%), which led to biased model results. A backward stepwise procedure was performed at a p value of 0.05 to identify the variables that remained significant in the final model. The co-linearity among the covariates was assessed by performing a variance inflation factor (VIF). None of the covariates presented a VIF value above the maximum acceptable value of 10. The data analysis was performed using STATA 13 [35]. Following Pullenayegum et al. [40]. Thus, the effectiveness of antenatal care in low-income countries depends on how well this service is provided [41] and the availability of other services, such as obstetric care [42].

Regarding the second objective of this study, according to our results, having good social support positively affects women’s HRQoL during the first postpartum year. Our findings are consistent with those of several other studies investigating social support as a predictor of the HRQoL during the postpartum period [7, 10, 13, 43]. Possible explanations include that poor social support is a general predictor of postpartum depression [44], stressful events, panic disorders, psychological distress [45], and a poor mental health status [46]. Furthermore, of the five EQ-5D domains, anxiety or depression had the highest proportion of women reporting moderate or severe problems. Social support after giving birth is particularly important in the Rwandan culture. Considering the numerous practices by family and friends that comfort women during the postpartum period, new mothers find it challenging to cope with the situation with inadequate social support.

Household wealth was another socio-economic determinant of women’s HRQoL during the postpartum period. Thus, our results add to the vast literature on health inequalities in different contexts. Several previous studies investigating women’s HRQoL during the postpartum period have demonstrated the influence of household wealth or income [7, 8, 11] or other closely related indicators, such as employment and standard of living [47]. In the model using the EQ-VAS as the outcome, marital status was also significantly associated with HRQoL. In this study, higher educational levels were not associated with better HRQoL. This finding is surprising given that other studies have found good education to be a key predictor of HRQoL [7, 11]. The lack of association between the educational level and HRQoL may be partially attributable to the community health program in Rwanda, which has reduced inequalities in the use of services [48]. Other studies have reported findings similar to ours regarding marital status [8, 37]. However, notably, marital status is not the same among women in different societies [49]. In the Rwandan context, being a single woman is often associated with stigma and has been associated with poor utilization of maternal health services such as antenatal care [50].

In this study, rural women had better HRQoL than did urban women. No consensus exists in the literature regarding the rural-urban differences in HRQoL. Several scholars have argued that rural populations are less likely to be educated and have limited access to infrastructures; therefore, these populations are likely to have lower HRQoL [51]. Other scholars argue that life in urban areas is more stressful, translating to a higher prevalence of anxiety, depression, or other mental health problems [9, 52]. This hypothesis may be supported by our findings because anxiety or depression was the dimension with the widest gap between the rural and urban women as follows: on average, 85% of the women living in rural areas reported not having any anxiety or depression problems, compared with 70% of the women living in urban areas.

Regarding the number of children, although this variable was excluded from the regression analysis, according to the bivariate analysis, women with six or more children had a significantly lower HRQoL than women with fewer children using the EQ-5D. Akýn et al. [7] also established a negative association between the number of children and women’s HRQoL during 12 months postpartum. For women in settings such as Rwanda, where many individuals are rural farmers who must perform farming activities along with caring for their families, partner support is limited, and having many children may be particularly stressful.

The association of the maternal age and age of the baby with HRQoL has been previously reported [7, 14, 53] but was not supported in this study.

Methodological limitations

A major strength of our study is that we present data on women’s HRQoL collected through a population-based survey. In low-income countries, such as Rwanda, most existing evidence on postpartum morbidity is health facility based; however, very few women with postpartum health problems seek health care [3, 54].

A limitation shared by this study and other studies in the literature is that the quality and content of the antenatal care service were not explored. ANC quality is potentially a determinant of postpartum HRQoL, and thus, there is a risk of omitted variable bias. Including the ANC quality in the analysis may have also enabled a better disentanglement of the role of adequate timing and number of visits. In the case of poor quality or when the content does not meet the required standard, ANC would unlikely have much impact on HRQoL. This limitation has been noted in other studies that assessed the effectiveness of antenatal care [18].

The difference between the two outcome measures (i.e., EQ-5D and EQ-VAS) is important. In our data, more variation was observed in the HRQoL using the EQ-VAS compared to that using the EQ-5D. The social support and wealth results were similar using both methods, but using the EQ-5D, the magnitude of the estimates was small, and the model only explained a small proportion of the overall variation. Lastly the cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow for inferences regarding causal-effect relationships.

Conclusions

Based on the findings in this study, the adequacy of antenatal care utilization, which is defined as at least four ANC visits and the first visit occurring during the first trimester, is associated with women’s HRQoL during the first postpartum year. Furthermore, having good social support and living in a wealthy household are associated with higher HRQoL. These results support the current call for decision-makers to consider the role of social determinants in maternal health and well-being. Ministries with health as one of their responsibilities should work more closely with other sectors, such as those in charge of economic development and social protection. Strategies that favor the creation and reinforcement of social networks among women of reproductive age should be promoted. For example, group antenatal care could be tested in Rwanda because it has been shown to have positive effects on women’s satisfaction and in creating social support networks [55].

Finally, the quality of antenatal care in Rwanda should be assessed by not only evaluating practice based on the Rwandan antenatal guidelines but also benchmarking the guidelines based on the most recent evidence of effective interventions that should be included in antenatal practice.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- EQ-5D:

-

European Quality of Life - 5 Dimensions

- EQ-5D-3L:

-

European Quality of Life - 5 Dimensions - 3 Levels

- EQ-VAS:

-

European Quality of Life - Visual Analogue Scale

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

References

Koblinsky M, Chowdhury ME, Moran A, Ronsmans C. Maternal morbidity and disability and their consequences: neglected agenda in maternal health. J Health Popul Nutr. 2012;30(2):124–30.

Firoz T, Chou D, von Dadelszen P, Agrawal P, Vanderkruik R, Tuncalp O, Magee LA, van Den Broek N, Say L. Measuring maternal health: focus on maternal morbidity. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(10):794–6.

Assarag B, Dubourg D, Maaroufi A, Dujardin B, De Brouwere V. Maternal postpartum morbidity in Marrakech: what women feel what doctors diagnose? BMC pregnancy childbirth. 2013;13:225.

Ferdous J, Ahmed A, Dasgupta SK, Jahan M, Huda FA, Ronsmans C, Koblinsky M, Chowdhury ME. Occurrence and determinants of postpartum maternal morbidities and disabilities among women in Matlab, Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2012;30(2):143–58.

Huang K, Tao F, Liu L, Wu X. Does delivery mode affect women's postpartum quality of life in rural China? J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(11–12):1534–43.

Grad FP. The preamble of the constitution of the World Health Organization. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80(12):981–4.

Akyn B, Ege E, Kocodlu D, Demiroren N, Yylmaz S. Quality of life and related factors in women, aged 15-49 in the 12-month post-partum period in Turkey. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2009;35(1):86–93.

Zugravu C-A, Rada C. Quality of life determinants for Romanian mothers in urban communities. Int J Collab Res Intern Med Pub Health. 2012;4(12):1884–92.

Zagozdzon P, Kolarzyk E, Marcinkowski JT. Quality of life and rural place of residence in Polish women—population based study. Annals agri environmental med AAEM. 2011;18(2):429–32.

Webster J, Nicholas C, Velacott C, Cridland N, Fawcett L. Quality of life and depression following childbirth: impact of social support. Midwifery. 2011;27(5):745–9.

Ahluwalia IB, Holtzman D, Mack KA, Mokdad A. Health-related quality of life among women of reproductive age: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 1998-2001. J women's health (2002). 2003;12(1):5–9.

Saravi FK, Navidian A, Rigi SN, Montazeri A. Comparing health-related quality of life of employed women and housewives: a cross sectional study from Southeast Iran. BMC Womens Health. 2012;12:41.

Coyle SB. Health-related quality of life of mothers: a review of the research. Health care women int. 2009;30(6):484–506.

Torkan B, Parsay S, Lamyian M, Kazemnejad A, Montazeri A. Postnatal quality of life in women after normal vaginal delivery and caesarean section. BMC pregnancy childbirth. 2009;9:4.

Bahrami N, Simbar M, Bahrami S. The effect of prenatal education on mother’s quality of life during the first year postpartum Iranian women—a randomized controlled trial. Intern J Fertility Sterility. 2013;7(3):169–74.

Hardee K, Gay J, Blanc AK. Maternal morbidity: neglected dimension of safe motherhood in the develo** world. Global pub health. 2012;7(6):603–17.

McDonagh M. Is antenatal care effective in reducing maternal morbidity and mortality? Health Policy Plan. 1996;11(1):1–15.

Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M. Assessing the role and effectiveness of prenatal care: history, challenges, and directions for future research. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(4):306–16.

Carroli G, Rooney C, Villar J. How effective is antenatal care in preventing maternal mortality and serious morbidity? An overview of the evidence. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15(Suppl 1):1–42.

Dowswell T, Carroli G, Duley L, Gates S, Gulmezoglu AM, Khan-Neelofur D, Piaggio GG. Alternative versus standard packages of antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy. Cochrane database syst rev. 2010;10:CD000934.

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes, 3rd edition. Oxford: Oxford university press; 2015.

Thacker SB, Stroup DF, Carande-Kulis V, Marks JS, Roy K, Gerberding JL. Measuring the public’s health. Public Health Rep. 2006;121(1):14–22.

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning of Rwanda: Rwanda fourth population and housing census 2012. Thematic report—population size, structure and distribution.; 2014.

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) [Rwanda], Ministry of Health (MOH) [Rwanda], and ICF International. 2015. Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2014-15. Rockville, Maryland, USA: NISR, MOH, and ICF International. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR316/FR316.pdf.

Fokom-Domgue J, Noubiap JJ. Diagnosis of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: a poorly assessed but increasingly important issue. J Clin Hypertens. 2015;17(1):70–3.

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda - NISR, Ministry of Health - MOH/Rwanda, ICF International: Rwanda demographic and health survey 2010.; 2012.

Corp I. IBM SPSS statistics for Mac OSX, version 22.0. NY: IBM Corp Armonk; 2013.

Cheung K, Oemar M, Oppe M, Rabin R. EQ-5D user guide: basic information on how to use EQ-5D. Rotterdam: EuroQol Group; 2009.

Kind P, Hardman G, Macran S: UK population norms for EQ-5D. University of York Centre for Health Economics. Discussion paper 172; 1999.

Beeckman K, Louckx F, Masuy-Stroobant G, Downe S, Putman K. The development and application of a new tool to assess the adequacy of the content and timing of antenatal care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:213.

World Health Organization: WHO antenatal care randomized trial manual for the implementation of the new model. 2002.

Gwatkin DR, Rustein S, Johnson K, Suliman E, Wagstaff A, Amouzou A. Socio-economic differences in health, nutrition, and population within develo** countries: an overview. Country reports on HNP and poverty. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/962091468332070548/. Accessed 23 Dec 2017.

Cooke BD, Rossmann MM, McCubbin HI, Patterson JM. Examining the definition and assessment of social support: a resource for individuals and families. Fam Relat. 1988;37(2):211–6.

Wang HH, Wu SZ, Liu YY. Association between social support and health outcomes: a meta-analysis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2003;19(7):345–51.

StataCorp L. Stata: release 13-statistical software. TX: College Station; 2013.

Pullenayegum EM, Tarride JE, **e F, Goeree R, Gerstein HC, O'Reilly D. Analysis of health utility data when some subjects attain the upper bound of 1: are Tobit and CLAD models appropriate? Value Health. 2010;13(4):487–94.

Parker L, Catunda HLO, Castro RCMB, Ribeiro SG, Ahn H, MFd O, Almeida PC, CGP C, AKB P, PdS A. Maternal predictors for quality of life during the postpartum in Brazilian mothers. Health. 2015;7:371–80.

Tayebi T, Zahrani ST, Mohammadpour R. Relationship between adequacy of prenatal care utilization index and pregnancy outcomes. Iranian journal of nursing and midwifery research. 2013;18(5):360–6.

Conway KS, Kutinova A. Maternal health: does prenatal care make a difference? Health Econ. 2006;15(5):461–88.

Zanconato G, Msolomba R, Guarenti L, Franchi M. Antenatal care in develo** countries: the need for a tailored model. Seminars in fetal & neonatal medicine. 2006;11(1):15–20.

Oyerinde K. Can antenatal care result in significant maternal mortality reduction in develo** countries. Journal of Community Medicine and Health Education. 2013;3(2):2–3.

Acharya S. How effective is antenatal care to promote maternal and neonatal health? Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1995;50:S35–42.

Hung CH, Chung HH. The effects of postpartum stress and social support on postpartum women’s health status. J Adv Nurs. 2001;36(5):676–84.

Morikawa M, Okada T, Ando M, Aleksic B, Kunimoto S, Nakamura Y, Kubota C, Uno Y, Tamaji A, Hayakawa N, et al. Relationship between social support during pregnancy and postpartum depressive state: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10520.

Maulik PK, Eaton WW, Bradshaw CP. The effect of social networks and social support on common mental disorders following specific life events. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122(2):118–28.

Da Costa D, Dritsa M, Rippen N, Lowensteyn I, Khalife S. Health-related quality of life in postpartum depressed women. Archives women’s mental health. 2006;9(2):95–102.

Hammoudeh W, Mataria A, Wick L, Giacaman R. In search of health: quality of life among postpartum Palestinian women. Exp rev pharmacoeconomics outcomes res. 2009;9(2):123–32.

Condo J, Mugeni C, Naughton B, Hall K, Tuazon MA, Omwega A, Nwaigwe F, Drobac P, Hyder Z, Ngabo F, et al. Rwanda’s evolving community health worker system: a qualitative assessment of client and provider perspectives. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12:71.

Han KT, Park EC, Kim JH, Kim SJ, Park S. Is marital status associated with quality of life? Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:109.

Rurangirwa AA, Mogren I, Nyirazinyoye L, Ntaganira J, Krantz G. Determinants of poor utilization of antenatal care services among recently delivered women in Rwanda; a population based study. BMC pregnancy childbirth. 2017;17(1):142.

Naseem K, Khurshid S, Khan SF, Moeen A, Farooq MU, Sheikh S, Bajwa S, Tariq N, Yawar A. Health related quality of life in pregnant women: a comparison between urban and rural populations. J Pakistan Med Assoc. 2011;61(3):308–12.

Esmaeilzadeh S, Agajani Delavar M, Aghajani Delavar MH. Assess quality of life among Iranian married women residing in rural places. Global J Health Sci. 2013;5(4):182–8.

Emmanuel EN, Sun J. Health related quality of life across the perinatal period among Australian women. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(11–12):1611–9.

Lagro M, Liche A, Mumba T, Ntebeka R, van Roosmalen J. Postpartum health among rural Zambian women. Afr J Reprod Health. 2003;7(3):41–8.

Homer CS, Ryan C, Leap N, Foureur M, Teate A, Catling-Paull CJ. Group versus conventional antenatal care for women. Cochrane database syst rev. 2012;11:CD007622.

Funding

This study is part of the Maternal Health Research Program (MaTHeR) undertaken by the University of Rwanda in collaboration with Gothenburg University and Umeå University with funding from the Swedish International Development Agency. The funder played no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or the writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. RH and JPSS collected the data in the field. RH analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LL and AMPB contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol and questionnaire were approved by the University of Rwanda, College of Medicine and Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (Ref: 010/UR/CMHS/SPH/2014). The participants were informed of their voluntary participation and right to withdraw at any stage of the study. A written informed consent form was signed by all participants before their participation in the study or by their legal guardians for participants below 18 years of age.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hitimana, R., Lindholm, L., Krantz, G. et al. Health-related quality of life determinants among Rwandan women after delivery: does antenatal care utilization matter? A cross-sectional study. J Health Popul Nutr 37, 12 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-018-0142-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-018-0142-4