Abstract

To mimic the Escherichia coli T7 protein expression system, we developed a facile T7 promoter-based protein expression system in an industrial microorganism Bacillus subtilis. This system has two parts: a new B. subtilis strain SCK22 and a plasmid pHT7. To construct strain SCK22, the T7 RNA polymerase gene was inserted into the chromosome, and several genes, such as two major protease genes, a spore generation-related gene, and a fermentation foam generation-related gene, were knocked out to facilitate good expression in high-density cell fermentation. The gene of a target protein can be subcloned into plasmid pHT7, where the gene of the target protein was under tight control of the T7 promoter with a ribosome binding site (RBS) sequence of B. subtilis (i.e., AAGGAGG). A few recombinant proteins (i.e., green fluorescent protein, α-glucan phosphorylase, inositol monophosphatase, phosphoglucomutase, and 4-α-glucanotransferase) were expressed with approximately 25–40% expression levels relative to the cellular total proteins estimated by SDS-PAGE by using B. subtilis SCK22/pHT7-derived plasmid. A fed-batch high-cell density fermentation was conducted in a 5-L fermenter, producing up to 4.78 g/L inositol monophosphatase. This expression system has a few advantageous features, such as, wide applicability for recombinant proteins, high protein expression level, easy genetic operation, high transformation efficiency, good genetic stability, and suitability for high-cell density fermentation.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The bacteriophage T7-protomer protein expression system is the most widely used technique of the production of recombinant proteins because of its simple genetic operation, high expression levels, and tightly regulated expression of targeted genes (Terpe 2006; Ting et al. 2020). It was first developed in the Gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli (Rosenberg et al. 1987). The T7–E. coli expression system consists of two important parts: (1) an expression plasmid containing a gene of interest under the control of the T7 promoter and (2) a T7 expression host, such as E. coli DE3, which has a chromosomal copy of the T7 RNA polymerase gene with the control of a lacUV5 promoter. The isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-induced T7 expression can be regulated by co-expressing the lac repressor from the plasmid and by co-expressing the T7 lysozyme, a natural inhibitor of T7 RNA polymerase (Moffatt and Studier 1987). Later, this system has been adapted to other organisms, such as Bacillus subtilis (Conrad et al. 1996), Bacillus megaterium (Gamer et al. 2009), Lactococcus lactis (Wells et al. 1993), Pseudomonas (Davison et al. 1989), Ralstonia eutropha (Barnard et al. 2004), Rhodobacter capsulatus (Drepper et al. 2005), Streptomyces lividans (Lussier et al. 2010), Shewanella oneidensis (Yi and Ng 2021), and so on.

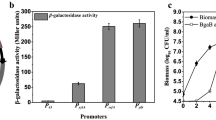

The Gram-positive bacterium B. subtilis is Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) microorganism due to its lack of pathogenicity and absence of endotoxins as well as its safe use as food and feed probiotics. It is one of the most important industrial hosts for the production of numerous proteins, especially homologous enzymes, such as α-amylase (Chen et al. 2015), protease (Dong et al. 2017; Wenzel et al. 2011), xylanase (Helianti et al. 2016; Rashid and Sohail 2021), lipase (Lu et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2020), β-glucanase (Niu et al. 2018), and so on (Schallmey et al. 2004; Terpe 2006). Also, a few heterogeneous enzymes have been over-expressed by B. subtilis by using different promoters (Harwood et al. 2002). For example, the natural strictly regulated xylose-inducible promoter PxylA in B. subtilis has been demonstrated to achieve modest expression levels (Bhavsar et al. 2001; Kim et al. 1996). Similarly, several natural inducible promoters of B. subtilis have been investigated, such as Pglv (Yang et al. 2006; Yue et al. 2017), PspaS (Bongers et al. 2005), Pgcv (Phan and Schumann 2007), and so on (Table 1). Furthermore, the heterologous Pspac promoter has been developed by fusing the 5ʹ-sequence of a promoter from the B. subtilis phage SPO1 and the 3ʹ-sequences of the E. coli lac promoter including its operator region and this promoter was inducible by a factor of 50 in terms of 1–10 mM IPTG (Yansura and Henner 1984). The Pgrac promoter and its derived mutants based on the strong promoter of the groESL operon harboring the lac operator enabled the overexpression of beta-galactosidase to achieve up to 53% of the total cellular protein (Phan et al. 2012, 2006; Tran et al. 2020). However, most of them did not have as high expression efficiencies as those of the T7–E. coli system (i.e., ~ 15–50%) and/or suffered from low transformation efficiency or time-consuming genetic operations. Therefore, it is needed to develop a facile heterologous protein expression system in B. subtilis.

Several efforts have been conducted to adapt the T7-promoter expression system into B. subtilis. The earliest attempt was conducted by Conrad et al. (Conrad et al. 1996). They designed an expression system composed of the T7 RNA polymerase under the control of xylose-inducible promoter PxylA and the gene of interest under the control of the T7 promoter. In it, the T7 polymerase gene was inserted in the amyE site of the chromosome, and the genes of interest (i.e., α-amylase, β-1,4-glucosidase, and β-galactosidase) were inserted into the respective plasmids. However, the heterologous enzymes were expressed only when an antibiotic rifampicin was added to inhibit the host's inherent RNA polymerase. Recently, Sun and his coworkers further improved the T7 promoter system in an undomesticated B. subtilis strain ATCC6051a (Ji et al. 2021). The T7 RNA polymerase gene under the control of the PxylA promoter was inserted in the aprE site chromosome for two purposes: to introduce the T7 RNA polymerase expression cassette and to break the native protease gene of the host. The expression frame of the target gene, which contains all the expression elements (i.e., T7 promoter, ribosome binding site sequence (RBS), the gene of interest, terminator) is highly similar to the pET21a vector, except that E. coli RBS (i.e., AAGGA) was replaced with the B. subtilis RBS sequence (i.e., AAGGAGG), and the whole expression frame was located in E. coli–B. subtilis shuttle vector pMK4 (Ji et al. 2021). To address the low transformation efficiency of B. subtilis, they inserted the comK gene responsible for the competence master regulator under the control of the xylose promoter in the nprE site of the chromosome (Zhang and Zhang 2011). They expressed approximately 1.0 g/L α-L-arabinofuranosidase in the LB media supplemented with 10 g/L xylose, which worked as both the inducer and carbon source. However, this system had two weaknesses, such as the genetic instability because the comK gene was ON in the presence of xylose because promoter PxylA controlled its expression, and the inducer was consumed continuously by the host. Another strategy to address genetic instability was the insertion of both the T7 RNA polymerase gene and the gene of interest into the chromosome (Castillo-Hair et al. 2019; Chen et al. 2010). IPTG-inducible promoters (e.g., Pspac or Phy-spank) were used to regulate the expression of T7 RNA polymerase and integrated the genes of interest into the adjacent or distant site in the chromosome (Castillo-Hair et al. 2019; Chen et al. 2010). However, genetic modification of the chromosome was time-consuming and suffered from low biotransformation efficiency.

To develop a better T7-promoter expression system for B. subtilis, we need address several issues, such as easy biotransformation of the host, facile preparation of the expression plasmid, and a good expression host whose major proteases were knocked out. In this study, we developed a new B. subtilis host that featured (1) an inducible comK gene (Zhang and Zhang 2011); (2) the knock-out of some inherent protease genes, such as aprE and nprE (Kawamura and Doi 1984); (3) the insertion of the constitutive expression of the T7 RNA polymerase in the chromosome, and (4) the knock-out of the sporulation gene spoIIAC (Higgins and Dworkin 2012) and surfactin synthase gene srfAC (Peypoux et al. 1999) related to fermentation foam generation. The targeted gene was placed in an episomal plasmid pHT01 under the control of a hybrid promoter T7-lac and its ribosome binding site sequence was derived from B. subtilis. For any new targeted protein, the users can easily prepare the plasmid by one-step genetic operation (i.e., restriction enzyme-free and sequence-independent), prolonged overlap extension polymerase chain reaction (POE-PCR) (You et al. 2012) and easily transform the host with high transformation efficiencies. We tested heterologous expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP), α-glucan phosphorylase (αGP), inositol monophosphatase (IMP), phosphoglucomutase (PGM), and 4-α-glucanotransferase (4GT) proteins in B. subtilis, and demonstrated its applicability in high-density fermentation.

Materials and methods

Materials

All chemicals used were of analytical grade or higher quality and purchased from Sinopharm (Bei**g, China), Aladdin (Shanghai, China), and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless specified. Taq DNA Polymerase was purchased from BioMed (Bei**g, China), PrimeSTAR MAX DNA Polymerase and Premixed Protein Marker (Low) were purchased from Takara (Dalian, China). Plasmid extraction and PCR purification kit were purchased from Tiangen Biotech (Bei**g, China).

Strains, plasmids, and cultivation conditions

Strains and plasmids used are listed in Table 2. Plasmids were constructed using the Simple Cloning technology (You et al. 2012). The primers (Table 3 and Additional file 1: Table S1) used for PCR were synthesized by GENEWIZ (Bei**g, China). B. subtilis SCK6 which was derived from B. subtilis 1A751 contains a genetic cassette expressing the comK gene in its genome (Zhang and Zhang 2011). An E. coli–B. subtilis shuttle vector pHT01 (Nguyen et al. 2007) was used to clone and express the desired recombinant protein. The strains were cultured in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium containing 0.5% yeast extract, 1% tryptone, and 1% NaCl at 37 °C. When necessary, the medium was supplemented with 5 mg/L chloramphenicol or 0.3 mg/L erythromycin.

Construction of the B. subtilis SCK22 strain

Figure 1 shows the design of the T7 expression system in B. subtilis. To construct a seamless knock-out system, the upp gene was knocked out as a negative selection marker gene. The upp gene encodes uracil phosphoribosyltransferase (UPRTase), which can catalyze pyrimidine analog 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) to 5-fluoro-dUMP, which is a strong inhibitor of thymidylate synthetase and leads to cell death. Deletion of upp endows the mutant strain with resistance to 5-FU (Dong and Zhang 2014).

Schematic representation of the industrial host SCK22 harboring plasmid pHT7. After xylose induction, under the control of xylose-inducible promoter, comK gene was expressed and then super receptive cells were formed. Endogenous protein genes and fermentation-related genes were knocked out on the genome to make it suitable for high-density fermentation. The P43 promoter enabled the constitutive expression of T7 RNA polymerase, and the expression plasmid encoded the target gene, where the T7 promoter was under the control of the lac operon

The knock-out of a gene in the chromosome was conducted by double-crossover homologous recombination (Shi et al. 2013). In brief, the upstream homology arm of the target gene including the direct repeat DR region, the upp gene, the antibiotic gene, and the downstream homology arm of the target gene including the DR region were sequentially connected to form large-size DNA multimers by prolonged overlap extension PCR and then were transferred into B. subtilis. Primer sequences used for PCR are in the supplementary materials (Additional file 1: Table S1).The first-round double- crossover homologous recombination occurred with the upp gene and antibiotic gene integrated into the chromosome through resistance plate screening. The correct transformants verified by PCR were cultured in the resistance-free medium, and the second-round homologous recombination occurred between the two DR regions. Thus, the target transformants, where the upp gene, resistance gene and the target gene were all deleted, could be obtained by using 5-FU plate screening.

For strains SCK8, SCK9 and SCK10, the upp, spoIIAC and srfAC genes were knocked out by using this seamless knock-out system, respectively. The pSS plasmid backbone, upstream homology arm of the target gene, upp gene fragment, chloramphenicol resistance gene fragment, and downstream homology arm gene of the target gene were sequentially connected to obtain an integration plasmid by prolonged overlap extension PCR (Morimoto et al. 2008; Shi et al. 2013). Subsequently, the plasmid was transferred into B. subtilis and the target transformants were obtained by two rounds of homologous recombination (Shi et al. 2013).

SCK22 was constructed based on the mutant strain SCK10. The integration vector pDG1730 was used as it contained a spectinomycin resistance gene sandwiched between amyE-front and amyE-back (Guerout-Fleury et al. 1996). The pDG1730 plasmid backbone, upp gene fragment, the upstream homology arm DR region and a DNA cassette encoding the T7 RNA polymerase with the P43 promoter were sequentially connected to obtain a new plasmid pDG1730-T7RNAP by using Simple Cloning (You et al. 2012). Then, the constructed integrated plasmid pDG1730-T7RNAP was transformed into B. subtilis SCK10 to obtain SCK22.

Construction of the pHT7-based expression vectors

The DNA fragment containing a T7-lac promoter, T7 terminator, and the B. subtilis RBS sequence (i.e., AAGGAGG) (Fig. 2A) was chemically synthesized. This sequence was subcloned into plasmid pHT01, yielding plasmid pHT7. The gfp gene derived from Aequorea victoria was selected as the gene of interest and inserted after the RBS sequence of the pHT7 plasmid (Fig. 2A and B). The insertion DNA fragment encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) was amplified by PCR with a pair of primers P1 and P2 (Table 3). The linear vector backbone was amplified from plasmid pHT7 with a pair of primers P3 and P4. The two PCR products were assembled by POE‐PCR. The POE‐PCR product was directly transformed into B. subtilis SCK22, yielding plasmid pHT7-GFP. The plasmid pHT7-GFP was used as the protein expression vector to verify and optimize the newly constructed T7 expression system. The other four enzyme expression plasmids (i.e., α-glucan phosphorylase (αGP) from the thermophilic bacterium Thermococcus kodakarensis, inositol monophosphatase (IMP) from Thermotoga maritima, phosphoglucomutase (PGM) from T. kodakarensis, and 4-α-glucanotransferase (4GT) from Thermococcus litoralis) were constructed in the same way (Fig. 2C). The gene sequences of these four enzymes were described elsewhere (You et al. 2017; Zhou et al. 2016).

Key DNA sequence before and after the gene of interest (A), plasmid map of pHT7-GFP (B) and scheme of plasmid multimerization (C). Plasmid pHT7-GFP contains the T7 promoter-terminator cassette including a lacO lactose operator and a SD sequence, the replication origin ori in E. coli, the replication origin repA in B. subtilis, the lac repressor gene, chloramphenicol-resistance gene and ampicillin-resistance gene

Transformation of the B. subtilis SCK22 strains

The transformation of B. subtilis SCK22 was performed as described elsewhere (Zhang and Zhang 2011) with minor modifications. The B. subtilis SCKC22 strain was spread on solid LB medium containing 0.3 mg/L erythromycin and then cultured overnight in 37 °C. Single colonies were picked from the plate and then inoculated in 3 mL of the LB liquid medium containing 0.3 mg/L erythromycin at 37 °C. The cell cultures were incubated in a 250 rpm shaker for 4 h. The cultures were then transferred to 50 mL of the LB medium and grew at 37 °C until the absorbency at 600 nm was approximately 0.6–0.8. Xylose (final concentration of 10 g/L) was added and cultured for 2 h. The resulting cell cultures were ready to be transformed as super-competent cells or divided into aliquots and stocked at − 80 °C with 10% (v/v) glycerol for future use (thawed for direct transformation). Then 1 μL of POE-PCR product was mixed with 100 μL of the super-competent cells, and then was incubated in a rotary shaking incubator at 200 rpm for 1.5 h at 37 °C. Spread the transformed competent cells on solid LB plate with the appropriate antibiotic and incubate the plate at 37 °C for 8–12 h to select transformants.

Heterologous protein expression

The SCK22 strains containing plasmids pHT7-GFP, pHT7-αGP, pHT7-IMP, pHT7-PGM or pHT7-4GT were cultured in small culture tubes overnight and then inoculated into 1-L shake flasks containing 200 mL of the LB liquid medium at 37 °C. The inoculum size was adjusted to allow the cell culture to have an absorbency of about 0.05 at 600 nm. When A600 was reached 0.8–1.0, IPTG was added, followed by 4 h of cell cultivation. After fermentation, the broth was centrifuged. The cell pellets were washed with the saline water once. The cell pellets were re-suspended in 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.0) containing 100 mM NaCl. After ultra-sonication and centrifugation, the supernatants containing all soluble proteins including the target protein were analyzed by SDS-PAGE according to the standard procedure. The gels were stained by Coomassie brilliant blue R250 staining.

Fluorescence measurement and quantification of GFP

Cell cultures of SCK22/pHT7-GFP were centrifuged at 12,000×g for 5 min to obtain bacterial cells and supernatants. After the bacterial cells were washed with the saline water once, they were re-suspended in the 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.0) containing 100 mM NaCl prior to disruption by ultra-sonication on an ice bath. The fluorescence intensities of the supernatants of cell lysates and fermentation broth represented the intracellular and extracellular GFP concentrations, respectively. The expression level of GFP protein was calculated according to the measured fluorescence intensity and fluorescence curve (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Cell growth was monitored by measuring its absorbance at 600 nm.

Fed-batch fermentation

The fermentation was carried out in a 5-L fermenter (T&J Bio-engineering Co., Shanghai, China). The fermentation medium consisted of the following components (per liter): 10 g of yeast extract, 0.2 g histidine, 20 g glycerol, 5.12 g Na2HPO4·12H2O, 3.0 g KH2PO4, 0.5 g NaCl, 0.5 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.011 g CaCl2, 1.0 g NH4Cl, 0.2 mL of 1% (w/v) vitamin B1, and 0.1 mL of the trace elements solution. The stock solution of trace elements contained the following (per liter) in 3 M HCl: 80 g FeSO4·7H2O, 10 g AlCl3·6H2O, 2.0 g ZnSO4·7HO, 1.0 g CuCl2·2H2O, 2.0 g NaMoO4·2H2O, 10 g MnSO4·H2O, 4.0 g CoCl2, and 0.5 g H3BO4. Appropriate antibiotics and defoamer were added if necessary.

The cryopreserved strains were inoculated into 50 mL of the LB medium containing 1% glucose and then cultured at 37 °C for 12 h with vigorous shaking. Then the entire cell cultures were transferred into the fermenter. Dissolved oxygen (DO) was monitored using a DO sensor and was maintained above 20% saturation by controlling both the aeration rate (2–18 L/min) and the agitation rate (200–1000 rpm). Foaming was controlled by the addition of the Sigma anti-foaming agent. After about 8 h cultivation, the DO shown a suddenly increased, indicating the complete consumption of carbon source. The feeding solution (i.e., 50% (g/g) glycerol, 5% (g/g) yeast extract, and 0.5% (g/g) histidine) was added slowly. The addition rate of the feeding solution was adjusted to be approximately 6–10 g/L/h according the growth rates of bacteria. The fermentation was performed at pH 6.8 and 37 °C, whereas the pH was adjusted with 25% (v/v) ammonia. The samples were collected at the indicated time intervals.

Protein analysis by SDS-PAGE

Cell culture samples were harvested and centrifuged at 12,000×g for 5 min. The pellets were re-suspended in 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.0) containing 100 mM NaCl. After ultra-sonication in an ice bath, cell debris were removed by centrifugation at 12,000×g for 5 min. After adding the SDS-PAGE loading buffer, the cell lysates and the supernatants of the cell lysates were incubated in a boiling water bath for 10 min and equal amounts of proteins were loaded into 12% SDS-PAGE gels. The Premixed Protein Marker (Low covering the 14.3 to 97.2 kDa range) (Takara Bio Inc., China) was used as a molecular mass marker. Following electrophoresis, proteins were visualized by Coomassie Brilliant Blue R250. The SDS-PAGE results were imaged and analyzed by Bio-Rad Gel Doc™ XR + Imaging System.

Other assays

The concentrations of the proteins were determined by the Bradford with bovine serum albumin as the reference. All data were averaged from three independent samples.

Results

Construction of the T7 expression system in B. subtilis

Figure 1 shows the design of the Bacillus T7 expression system. Similar to the E. coli T7 system, it had two parts: a plasmid encoding the gene of interest which was under control of the T7 promoter, and a Bacillus host whose chromosome had a T7 RNA polymerase gene under the control of a constitutive P43 promoter. First, because B. subtilis has much lower transformation efficiency than E. coli and it was time-consuming to prepare competent cells, the DNA cassette containing the comK gene under the control of the inducible PxylA promoter was inserted into its chromosome, wherein the ComK of B. subtilis was the master regulator for competence development (Mironczuk et al. 2008; Zhang and Zhang 2011). The induced super-competent cells of B. subtilis exhibited transformation efficiencies of ~ 107 transformants per μg of multimeric plasmid DNA (Zhang and Zhang 2011). Second, similar to the ompT- and ion-deficient E. coli BL21, two Bacillus protease genes (i.e., aprE and nprE) were knocked out from the chromosome so that the host was suitable for the expression of recombinant protein. Third, to avoid sporulation during its fermentation, the spoIIAC gene (RNA polymerase sigma-F factor) was knocked out (Zhang et al. 2016). Fourth, the surfactin synthase gene srfAC (surfactin synthase subunit 3) was also knocked out because its expression could form broth foam, impairing high-density fermentation (Zhang et al. 2016). Last, the T7 RNA polymerase gene with its P43 promoter was inserted into the amyE gene of the chromosome, yielding the T7 expression host B. subtilis SCK22.

Expression plasmid pHT7 (Fig. 2) was constructed to contain a T7-lac hybrid promoter, B. subtilis RBS sequence (i.e., AAGGAGG), the gene of interest (e.g., green fluorescent protein, gfp) and the T7 terminator, based on pHT01 plasmid. The partial DNA sequence of plasmid pHT7 before and after the gene of interest is presented in Fig. 2A. In the absence of the inducer IPTG, a repressor protein (LacI) that repressed T7-lac promoter transcription prevented the target gene from being synthesized. When IPTG was added, it would bind to LacI and release the tetrameric repressor from the lac operator, thereby allowing the transcription of the T7-lac operon followed by the synthesis of a large amount of the targeted protein.

Flask fermentation and optimization

The strain SCK22 harboring plasmid pHT7-GFP was cultured in 1-L flasks, wherein the amount of green fluorescent proteins could be quantitated by measuring the fluorescence intensity of GFP. The profile of the fermentation of strain SCK22/pHT7-GFP is shown in Fig. 3A. The absorbency of cells at A600 rose to 4.1 at the 7th hour and then declined slowly. When the A600 was about 1.0, 0.5 mM IPTG was added. GFP was synthesized after IPTG addition and its concentration kept increasing to 0.16 g/L. After 4-h induction, nearly all GFP was intracellular and the GFP content relative to its total cellular protein was approximately 21%. Because some fraction of cells began to lyse after reaching the highest cell density, approximately a third GFP was released to the broth at the end of fermentation. SDS-PAGE analysis also shows the increased GFP expression over time (Fig. 3B). The intracellular GFP content gradually increased to 19.6% after IPTG addition until it reached the maximum after 4 h.

We also tested the optimal IPTG concentration from 0 to 2.0 mM (Fig. 4). The maximum intracellular GFP concentration (0.146 g/L) was obtained when IPTG was 1.0 mM. The GFP content was 22.4% relative to the total cellular protein.

Synthesis of four other heterologous proteins

We tested the applicability of this expression to four other proteins. They were αGP from T. kodakarensis, IMP from T. maritima, PGM from T. kodakarensis, and 4GT from T. litoralis. These thermophilic enzymes were used to synthesize inositol from starch in vitro (You et al. 2017; Zhou et al. 2016). Their expression was initiated by adding 1.0 mM IPTG when A600 reached approximately 0.8–1.0. SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5) shows that the expression levels of αGP, IMP, PGM, and 4GT were 31.7%, 26.3%, 24.3%, and 40.3%, respectively. There were no inclusion bodies found for all cases (Fig. 5), which was confirmed by the measuring the difference of protein concentrations in the cell lysate and its supernatants. These results suggested that this Bacillus T7 expression system can be used to express numerous heterologous proteins efficiently.

Fed-batch high-cell-density fermentation

To investigate whether the newly constructed T7 expression system is suitable for high-density fermentation, B. subtilis SCK22/pHT7-IMP was tested in fed-batch fermentation. As shown in Fig. 6, after 8 h fermentation, the feeding solution was added. With the feed addition, the cell concentration continued to increase (A600 up to 129.6). When 1.0 mM IPTG was added at 10 h, the IMP was synthesized. After 30 h fermentation, the intracellular IMP expression level reached a peak, accounting for 27.2% of the total intracellular protein, and the IMP titer was 4.78 g/L. Afterwards, the intracellular expression level of IMP declined due to cell lysis. SDS-PAGE analysis was also conducted to obtain of the relative percentage of intracellular IMP to the total cellular protein (Additional file 1: Figure S2). These results showed that this Bacillus T7 expression system was also suitable for high-density fermentation.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a simple Bacillus T7 protein expression system. This system contained a B. subtilis SCK22 host recombinant strain and a plasmid pHT7. The host was deficient in two major protease genes (i.e., aprE and nprE), a sporulation gene and (spoIIAC), and a surfactin synthase genes srfAC. Two genes were inserted its chromosome: the xylose-inducible comK gene for high transformation and the constitutive T7 RNA polymerase gene. With an available B. subtilis SCK22, it was easy and fast to construct the expression plasmid by using POE-PCR and transform into the host with high transformation efficiency. Five heterologous proteins were expressed efficiently in this system. As compared to other Bacillus T7-derived expression systems (Castillo-Hair et al. 2019; Chen et al. 2010; Conrad et al. 1996; Ji et al. 2021), this system featured its wide applicability, easy genetic operation, high expression capacity in both flask and fed-batch fermentation, and tightly controlled synthesis of the target protein.

It was notable that this Bacillus T7 expression synthesis could be superior to the E. coli counterpart for some proteins. It found out that at least a half of recombinant 4GT synthesized was inclusion bodies when it was expressed in E. coli (Additional file 1: Figure S3) although its expression conditions were intensively optimized, for example, decreased protein synthesis temperature, various IPTG concentration, codon optimization, co-expression of multiple chaperones (Duan et al. 2019). In contrast, there was not a significant amount of inclusion body observed when it was expressed in Bacillus. The reasons behind the better protein synthesis and folding in the Bacillus T7 expression could be under further investigation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, to develop a better T7-promoter expression system for B. subtilis, the strain SCK22 with high transformation efficiency and suitable for high-density fermentation was constructed by double-crossover homologous recombination, and the plasmids were constructed easily by simple cloning. The intracellular expression level of heterologous proteins reached the highest level of 25% ~ 40% at 4 h after 1.0 mM IPTG induction. The yield of IMP reached 4.78 g/L in high-density fermentation. In summary, the Bacillus T7 expression system has the advantages of simple genetic operation, stable expression of heterologous proteins, wide applicability, and suitable for high-density fermentation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting this article are included in the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- RBS:

-

Ribosome binding site

- SDS:

-

Sodium dodecyl sulfate

- PAGE:

-

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- IPTG:

-

Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside

- GRAS:

-

Generally recognized as safe

- POE-PCR:

-

Prolonged overlap extension polymerase chain reaction

- GFP:

-

Green fluorescent protein

- αGP:

-

α-Glucan phosphorylase

- IMP:

-

Inositol monophosphatase

- PGM:

-

Phosphoglucomutase

- 4GT:

-

4-α-Glucanotransferase

- LB:

-

Luria–Bertani

- UPRTase:

-

Uracil phosphoribosyltransferase

- 5-FU:

-

5-Fluorouracil

- DO:

-

Dissolved oxygen

References

Barnard GC, Henderson GE, Srinivasan S, Gerngross TU (2004) High level recombinant protein expression in Ralstonia eutropha using T7 RNA polymerase based amplification. Protein Expr Purif 38:264–271

Bhavsar AP, Zhao X, Brown ED (2001) Development and characterization of a xylose-dependent system for expression of cloned genes in Bacillus subtilis: conditional complementation of a teichoic acid mutant. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:403–410

Bongers RS, Veening JW, Van Wieringen M, Kuipers OP, Kleerebezem M (2005) Development and characterization of a subtilin-regulated expression system in Bacillus subtilis: strict control of gene expression by addition of subtilin. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:8818–8824

Castillo-Hair SM, Fujita M, Igoshin OA, Tabor JJ (2019) An engineered B. subtilis inducible promoter system with over 10000-fold dynamic range. ACS Synth Biol 8:1673–1678

Chen J, Fu G, Gai Y, Zheng P, Zhang D, Wen J (2015) Combinatorial Sec pathway analysis for improved heterologous protein secretion in Bacillus subtilis: identification of bottlenecks by systematic gene overexpression. Microb Cell Fact 14:92

Chen PT, Shaw JF, Chao YP, David Ho TH, Yu SM (2010) Construction of chromosomally located T7 expression system for production of heterologous secreted proteins in Bacillus subtilis. J Agric Food Chem 58:5392–5399

Conrad B, Savchenko RS, Breves R, Hofemeister J (1996) A T7 promoter-specific, inducible protein expression system for Bacillus subtilis. Mol Gen Genet 250:230–236

Davison J, Chevalier N, Brunel F (1989) Bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase-controlled specific gene expression in Pseudomonas. Gene 83:371–375

Dong H, Zhang D (2014) Current development in genetic engineering strategies of Bacillus species. Microb Cell Fact 13:63

Dong YZ, Chang WS, Chen PT (2017) Characterization and overexpression of a novel keratinase from Bacillus polyfermenticus B4 in recombinant Bacillus subtilis. Bioresour Bioprocess 4:47

Drepper T, Arvani S, Rosenau F, Wilhelm S, Jaeger KE (2005) High-level transcription of large gene regions: a novel T(7) RNA-polymerase-based system for expression of functional hydrogenases in the phototrophic bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus. Biochem Soc Trans 33:56–58

Duan X, Zhang X, Shen Z, Su E, Zhao L, Pei J (2019) Efficient production of aggregation prone 4-alpha-glucanotransferase by combined use of molecular chaperones and chemical chaperones in Escherichia coli. J Biotechnol 292:68–75

Gamer M, Frode D, Biedendieck R, Stammen S, Jahn D (2009) A T7 RNA polymerase-dependent gene expression system for Bacillus megaterium. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 82:1195–1203

Guerout-Fleury AM, Frandsen N, Stragier P (1996) Plasmids for ectopic integration in Bacillus subtilis. Gene 180:57–61

Harwood CR, Wipat A, Prágai Z (2002) Functional analysis of the Bacillus subtilis genome. Method Microbiol 33:337–367

Helianti I, Ulfah M, Nurhayati N, Suhendar D, Finalissari AK, Wardani AK (2016) Production of xylanase by recombinant Bacillus subtilis DB104 cultivated in agroindustrial waste medium. HAYATI J Biosci 23:125–131

Higgins D, Dworkin J (2012) Recent progress in Bacillus subtilis sporulation. FEMS Microbiol Rev 36:131–148

Ji MH, Li SJ, Chen A, Liu YH, **e YK, Duan HY, Shi JP, Sun JS (2021) A wheat bran inducible expression system for the efficient production of alpha-L-arabinofuranosidase in Bacillus subtilis. Enzyme Microb Technol 144:109726

Kawamura F, Doi RH (1984) Construction of a Bacillus subtilis double mutant deficient in extracellular alkaline and neutral proteases. J Bacteriol 160:442–444

Kim L, Mogk A, Schumann W (1996) A xylose-inducible Bacillus subtilis integration vector and its application. Gene 181:71–76

Lu YP, Lin Q, Wang J, Wu YF, Bao WYDL, Lv FX, Lu ZX (2010) Overexpression and characterization in Bacillus subtilis of a positionally nonspecific lipase from Proteus vulgaris. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 37:919–925

Lussier FX, Denis F, Shareck F (2010) Adaptation of the highly productive T7 expression system to Streptomyces lividans. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:967–970

Mironczuk AM, Kovacs AT, Kuipers OP (2008) Induction of natural competence in Bacillus cereus ATCC14579. Microb Biotechnol 1:226–235

Moffatt BA, Studier FW (1987) T7 lysozyme inhibits transcription by T7 RNA polymerase. Cell 49:221–227

Morimoto T, Kadoya R, Endo K, Tohata M, Sawada K, Liu S, Ozawa T, Kodama T, Kakeshita H, Kageyama Y, Manabe K, Kanaya S, Ara K, Ozaki K, Ogasawara N (2008) Enhanced recombinant protein productivity by genome reduction in Bacillus subtilis. DNA Res 15:73–81

Nguyen HD, Phan TT, Schumann W (2007) Expression vectors for the rapid purification of recombinant proteins in Bacillus subtilis. Curr Microbiol 55:89–93

Niu CT, Liu CF, Li YX, Zheng FY, Wang JJ, Li Q (2018) Production of a thermostable 1,3–1,4-beta-glucanase mutant in Bacillus subtilis WB600 at a high fermentation capacity and its potential application in the brewing industry. Int J Biol Macromol 107:28–34

Peypoux F, Bonmatin JM, Wallach J (1999) Recent trends in the biochemistry of surfactin. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 51:553–563

Phan TT, Nguyen HD, Schumann W (2012) Development of a strong intracellular expression system for Bacillus subtilis by optimizing promoter elements. J Biotechnol 157:167–172

Phan TT, Nguyen HD, Schumann W (2006) Novel plasmid-based expression vectors for intra- and extracellular production of recombinant proteins in Bacillus subtilis. Protein Expr Purif 46:189–195

Phan TT, Schumann W (2007) Development of a glycine-inducible expression system for Bacillus subtilis. J Biotechnol 128:486–499

Rashid R, Sohail M (2021) Xylanolytic Bacillus species for xylooligosaccharides production: a critical review. Bioresour Bioprocess 8:16

Rosenberg AH, Lade BN, Chui DS, Lin SW, Dunn JJ, Studier FW (1987) Vectors for selective expression of cloned DNAs by T7 RNA polymerase. Gene 56:125–135

Schallmey M, Singh A, Ward OP (2004) Developments in the use of Bacillus species for industrial production. Can J Microbiol 50:1–17

Shi T, Wang GL, Wang ZW, Fu J, Chen T, Zhao XM (2013) Establishment of a markerless mutation delivery system in Bacillus subtilis stimulated by a double-strand break in the chromosome. PLoS ONE 8:e81370

Terpe K (2006) Overview of bacterial expression systems for heterologous protein production: from molecular and biochemical fundamentals to commercial systems. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 72:211–222

Ting WW, Tan SI, Ng IS (2020) Development of chromosome-based T7 RNA polymerase and orthogonal T7 promoter circuit in Escherichia coli W3110 as a cell factory. Bioresour Bioprocess 7:54

Tran DTM, Phan TTP, Doan TTN, Tran TL, Schumann W, Nguyen HD (2020) Integrative expression vectors with Pgrac promoters for inducer-free overproduction of recombinant proteins in Bacillus subtilis. Biotechnol Rep 28:e00540

Wells JM, Wilson PW, Norton PM, Le Page RW (1993) A model system for the investigation of heterologous protein secretion pathways in Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol 59:3954–3959

Wenzel M, Muller A, Siemann-Herzberg M, Altenbuchner J (2011) Self-inducible Bacillus subtilis expression system for reliable and inexpensive protein production by high-cell-density fermentation. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:6419–6425

Wu FY, Ma JY, Cha YP, Lu DL, Li ZW, Zhuo M, Luo XC, Li S, Zhu MJ (2020) Using inexpensive substrate to achieve high-level lipase A secretion by Bacillus subtilis through signal peptide and promoter screening. Process Biochem 99:202–210

Yang MM, Zhang WW, Zhang XF, Cen PL (2006) Construction and characterization of a novel maltose inducible expression vector in Bacillus subtilis. Biotechnol Lett 28:1713–1718

Yansura DG, Henner DJ (1984) Use of the Escherichia-coli lac repressor and operator to control gene-expression in Bacillus subtilis. PNAS 81:439–443

Yi YC, Ng IS (2021) Redirection of metabolic flux in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 by CRISPRi and modular design for 5-aminolevulinic acid production. Bioresour Bioprocess 8:13

You C, Shi T, Li YJ, Han PP, Zhou XG, Zhang Y-HP (2017) An in vitro synthetic biology platform for the industrial biomanufacturing of myo-inositol from starch. Biotechnol Bioeng 114:1855–1864

You C, Zhang XZ, Zhang Y-HP (2012) Simple cloning via direct transformation of PCR product (DNA Multimer) to Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:1593–1595

Yue J, Fu G, Zhang DW, Wen JP (2017) A new maltose-inducible high-performance heterologous expression system in Bacillus subtilis. Biotechnol Lett 39:1237–1244

Zhang K, Duan X, Wu J (2016) Multigene disruption in undomesticated Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6051a using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Sci Rep 6:27943

Zhang XZ, Zhang Y-HP (2011) Simple, fast and high-efficiency transformation system for directed evolution of cellulase in Bacillus subtilis. Microb Biotechnol 4:98–105

Zhou W, You C, Ma H, Ma Y, Zhang Y-HP (2016) One-pot biosynthesis of high-concentration alpha-glucose 1-phosphate from starch by sequential addition of three hyperthermophilic enzymes. J Agric Food Chem 64:1777–1783

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Tian** Synthetic Biotechnology Innovation Capacity Improvement Project (TSBICIP-KJGG-003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JY, YJL, YQB, TZ and WJ designed experiments, performed experiments, and analyzed data; YHZ, TS and ZJW conceived the idea and supervised the research. JY, YJL and YHZ wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All of the authors have read and approved to submit it to Bioresources and Bioprocessing.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file1:

Figure S1. The standard curve of GFP protein concentration and its fluorescence intensity. Figure S2. SDS-PAGE analysis of IMP of B. subtilis SCK22/pHT7-IMP in a 5-L fermenter over time. Lanes: M, protein markers; T, the cell lysate; S, the supernatant of the cell lysate. Figure S3. SDS-PAGE analysis of expression of 4-α-glucanotransferase (4GT) from Thermococcus litoralis in E.coli BL21(DE3). Lanes: M, protein markers; T, the cell lysate; S, the supernatant of the cell lysate. Table S1. Primers for gene knockout.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, J., Li, Y., Bai, Y. et al. A facile and robust T7-promoter-based high-expression of heterologous proteins in Bacillus subtilis. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 9, 56 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-022-00540-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-022-00540-4