Abstract

Background

Malaria caused by Plasmodium species is a prominent public health concern worldwide, and the infection of a malarial parasite is transmitted to humans through the saliva of female Anopheles mosquitoes. Plasmodium invasion is a rapid and complex process. A critical step in the blood-stage infection of malarial parasites is the adhesion of merozoites to red blood cells (RBCs), which involves interactions between parasite ligands and receptors. The present study aimed to investigate a previously uncharacterized protein, PbMAP1 (encoded by PBANKA_1425900), which facilitates Plasmodium berghei ANKA (PbANKA) merozoite attachment and invasion via the heparan sulfate receptor.

Methods

PbMAP1 protein expression was investigated at the asexual blood stage, and its specific binding activity to both heparan sulfate and RBCs was analyzed using western blotting, immunofluorescence, and flow cytometry. Furthermore, a PbMAP1-knockout parasitic strain was established using the double-crossover method to investigate its pathogenicity in mice.

Results

The PbMAP1 protein, primarily localized to the P. berghei membrane at the merozoite stage, is involved in binding to heparan sulfate-like receptor on RBC surface of during merozoite invasion. Furthermore, mice immunized with the PbMAP1 protein or passively immunized with sera from PbMAP1-immunized mice exhibited increased immunity against lethal challenge. The PbMAP1-knockout parasite exhibited reduced pathogenicity.

Conclusions

PbMAP1 is involved in the binding of P. berghei to heparan sulfate-like receptors on RBC surface during merozoite invasion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria remains one of the world’s most important fatal diseases, with at least 241 million malaria cases and 627,000 malaria deaths recorded worldwide each year [1]. The growth and replication of Plasmodium parasites in red blood cells (RBCs) and the rupture of infected RBCs (iRBCs) are responsible for most symptoms of malaria [2]. Therefore, the blood stage of the parasites is the primary target for intervention. The process of erythrocyte invasion by the merozoites involves four continuous steps: attachment of a merozoite to the erythrocyte surface, followed by apical reorientation, tight junction formation, and final invasion [3]. As the adhesion of a merozoite to the RBC surface is essential to complete invasion, it is logical to believe that molecules presented on the merozoite surface play a critical role in this process. To date, several merozoite surface proteins as well as rhoptry- and microneme-derived proteins have been shown to play roles in the invasion process [4]. However, many proteins are associated with erythrocyte invasion, the functions of which remain to be explored further.

Heparan sulfate (HS), a non-branched polysaccharide of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), which are widely distributed on the surface of vertebrate cells, is utilized by Apicomplexan parasites to invade host cells [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. The adhesion of Toxoplasma gondii surface antigens and secreted proteins to host cells via heparin/HS has been reported. Specifically, T. gondii invasion-related proteins, such as surface protein 1 (SAG1), rhoptry protein 2 (ROP2), ROP4, and dense granule antigen 2 (GRA2), bind heparin [12]. HS is an essential receptor for Plasmodium falciparum that recognizes erythrocytes prior to invasion. HS also functions as a receptor for P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1), a parasite virulent factor associated with rosette formation that can adhere to normal erythrocytes [13, 14]. In addition, P. falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 (PfMSP-1), reticulocyte-binding homolog (PfRH5), and erythrocyte-binding protein (PfEBA-140) have been reported to bind to HS on the surface of RBCs and are disrupted by heparin [11, 15, 16]. Additionally, HS inhibits the invasion of erythrocytes by Plasmodium berghei [1: Table S1.

Confirmation of PbMAP1 expression in gene-edited parasites with southern blotting

Southern blotting of PbMAP1 and ΔPbMAP1 parasites was performed using the DIG High Prime DNA Labelling and Detection Starter Kit (Roche) according to the product manual. Briefly, genomic DNA was digested by Hind III for 1 h at 37 °C and separated on a 0.8% agarose gel for southern blotting onto a Hybond N+ nylon transfer membrane (Millipore). The target gDNA bands were hybridized with a digoxigenin-labeled DNA probe complementary to PbMAP1 and detected using an anti-digoxigenin AP-conjugated antibody. The primers used for probe amplification are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Infectivity tests of mice with wild-type P. berghei and gene-edited strains

For comparison the infectivity of wild-type P. berghei and gene-edited strains, 90 female BALB/c mice were randomly divided into nine groups of 10 mice each and were intraperitoneally administered with specific doses (1 × 103, 1 × 104, or 1 × 106) of P. berghei wild-type (WT), ΔPbMAP1 (knockout strain), or ReΔPbMAP1 (the gene re-complement strain) strains. Parasitemia was assessed daily by counting cells in Giemsa-stained smears from a droplet of tail blood. Animals were monitored daily for survival.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

The parasites were harvested from the blood of BALB/c mice infected with WT or ΔPbMAP1 strains. Total RNA was extracted [23] from the parasite pellets using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), dissolved in RNase-free pure water, and quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Nanodrop 2000/2000c). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from random primer mixes using PrimeScript RT Enzyme Mix I (Takara), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Specific primers (Additional file 1: Table S1) were designed to detect the mRNA transcription of certain genes after PbMAP1 knockout. The cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 5 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. The housekee** gene actin (PBANKA_1459300) was used to normalize the transcriptional level of each gene.

Serum cytokine analyses

Levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, MCP-1, CCL4, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-12p70 in mouse sera were determined using the Cytometric Bead Array Mouse Inflammation kit (BD Biosciences). Samples were assayed according to the standard protocol (BD Biosciences) and examined using the FACSAria III flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) driven by the FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences).

Results

The sequence of PbMAP1 is conserved across Plasmodium species

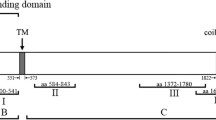

The gene coding for PbMAP1 is located on chromosome 14 and encodes a protein of 1303 amino acids, which is predicted to contain a signal peptide at the N-terminus (Fig. 1A). The amino acid sequence of PbMAP1 is relatively conserved across Plasmodium species, with > 70% identity among P. yoelii, P. chabaudi, and P. vinckei orthologs, > 40% identity across species infecting humans (including the zoonotic P. knowlesi), and > 43% identity with species infecting apes (Fig. 1B, 1C).

Sequence analysis of PbMAP1. A PbMAP1 is 1303-amino acid long and predicted to contain a signal peptide. B Identity in amino acid sequence between PbMAP1 and orthologous sequences from other Plasmodium species. C Alignment of amino acid sequence of PbMAP1 with orthologs of Plasmodium species (sequence identities are listed in the Methods section). The putative heparin binding motifs in the sequences are highlighted in the red box

PbMAP1 specifically binds heparin

To demonstrate the properties of PbMAP1 binding to heparin, the recombinant protein GST-PbMAP1 was purified. GST-PbMAP1 could bind to heparin-Sepharose but not to Sepharose, whereas GST could not bind to heparin (Fig. 2A). The competitive inhibition assay revealed that with an increase in heparin concentration, the binding amount of GST-PbMAP1 to heparin decreased gradually (Fig. 2B); however, no significant change in the binding of GST-PbMAP1 to heparin was noted with increase in CSA concentration (Fig. 2C).

GST-PbMAP1 specifically bound to heparin. A Heparin-binding activity was detected using western blotting with anti-GST antibody. GST-PbMAP1 could bind heparin-Sepharose but not Sepharose. GST could not bind heparin-Sepharose. B Competitive inhibition was detected using western blotting with an anti-GST antibody. As the heparin concentration increased, GST-PbMAP1 binding with heparin-Sepharose gradually decreased. C As the CSA concentration increased, no significant changes in GST-PbMAP1 binding with heparin-Sepharose were noted

Recombinant PbMAP1 could specifically bind to mouse RBCs

GST-PbMAP1 and GST were incubated with RBCs and analyzed using IFA, western blotting, and flow cytometry. IFA showed that the RBCs incubated with GST-PbMAP1 exhibited specific green fluorescence on the surface, whereas the RBCs incubated with GST alone showed no fluorescence (Fig. 3A). Western blotting showed that specific target bands were detected for RBCs incubated with GST-PbMAP1, while no bands were detected for RBCs incubated with GST alone (Fig. 3B). The binding of GST-PbMAP1 to RBCs was analyzed using flow cytometry, and the results confirmed that PbMAP1 could bind to RBCs (Fig. 3C). Therefore, PbMAP1 could bind to the surface of RBCs.

GST-PbMAP1 binds to mouse RBCs. A Indirect immunofluorescence assay using an anti-GST antibody as the primary antibody and Alexa Fluor 488 Goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) as the secondary antibody shows the binding of GST-PbMAP1 to RBCs. GST was used as the control. Scale bar, 5 μm. B Western blotting using an anti-GST antibody shows the binding of GST-PbMAP1 to RBCs. C Cell flow cytometry analysis of erythrocyte binding by the GST-PbMAP1 with GST as a control. A clear shift is observed with GST-PbMAP1-bound erythrocytes. D The fluorescence intensity of erythrocytes bound with GST- PbMAP1 compared to that with GST and blank controls

PbMAP1 localization on merozoites

To investigate the localization of PbMAP1 in merozoites, western blotting, IFA, and immunoelectron microscopy were performed using PbMAP1-specific antibodies. Western blotting confirmed PbMAP1 expression in merozoites. Next, we analyzed the expression and localization of PbMAP1 using IFA. Fluorescence was observed on the surface on free merozoites and that in the schizonts. Immunoelectron microscopy further verified that PbMAP1 was mainly located on the plasma membrane (Fig. 4A–C).

PbMAP1 is expressed in merozoites. A Western blotting of native PbMAP1 expressed in Plasmodium berghei merozoite detected using PbMAP1-specific antibodies. B Indirect immunofluorescence of PbMAP1. Free merozoites and parasite at ring-, trophozoite-, and schizont stages were fixed, and PbMAP1 expression was detected with anti-PbMAP1 IgG (green). Parasite nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). C Immune electron microscopy images of PbMAP1. The gold particles were localized to the merozoite membrane. Scale bar, 500 nm

Immunization with PbMAP1-specific peptides protects against infection

In this assay, we aimed to determine whether PbMAP1-specific antibodies protected the host from parasitic infections in vivo. BALB/c mice (N = 10 per group) were immunized four times with specific peptides. The mice with high antibody titers were injected with 1 × 106 iRBCs, and their survival time and parasitemia were measured. The mice immunized with specific peptides showed significantly longer survival (Fig. 5A, B). Furthermore, hyperimmune serum was collected and intravenously injected into BALB/c mice, followed by the injection of 1 × 106 iRBCs. The survival of the mice injected with anti-PbMAP1 serum was significantly longer than that of the control mice. Therefore, PbMAP1 antibodies could inhibit the invasion of parasites and produce immune-protective effects (Fig. 5C, D).

PbMAP1-specific antibodies generated protective immunity against Plasmodium berghei ANKA. A, B BALB/c mice without any immunization (control) exhibited 1.70-fold higher parasitemia than PbMAP1 peptide-immunized mice on day 11 post-infection; the error bars indicate SD. Mice immunized with PbMAP1 peptides survived 6 days longer than control mice. C, D Mice injected with serum from a normal infected mouse exhibited 1.86-fold higher parasitemia than those injected with anti-PbMAP1 sera on day 11 post-infection. Compared with the normal mouse serum group, the anti-PbMAP1 serum group survived for 6 days longer; the error bars indicate SD

Establishment of a PbMAP1-knockout (ΔPbMAP1) strain

We examined whether PbMAP1 is a key factor for binding to the surface of RBCs by knocking out the PbMAP1 gene from the parasite (Fig. 6A). The knockout strain (ΔPbMAP1) was cloned and verified using PCR with specific primers (Fig. 6B). Moreover, western blotting confirmed virtually complete deletion of PbMAP1 (Fig. 6C), and no signal was detectable in southern blotting in the ΔPbMAP1 strain (Fig. 6D).

Construction of a PbMAP1-knockout strain (ΔPbMAP1). A Scheme of the transfection plasmid used to target and knock out PbMAP1 in the PbANKA strain using the double-crossover method. B PCR validation of PbMAP1 deletion. PCR products from 5'-UTR, 3′-UTR, and PbMAP1 showed that PbMAP1 was replaced by DHFR. C Western blotting of PbMAP1 expression in WT and ΔPbMAP1. Protein bands with expected molecular weights are shown. No PbMAP1 protein was detected in the knockout strain. GAPDH was used as the control. D Southern blotting using a DNA probe from the PbMAP1 gene in WT and ΔPbMAP1. The gene encoding PbMAP1 was completely deleted in the knockout strain

Construction of the PbMAP1 gene re-complement (ReΔPbMAP1) strain

To demonstrate that the phenotype defect was due to the deletion of the gene coding for PbMAP1, we re-introduced the PbMAP1 gene without intron at the endogenous PbMAP1 locus in the ΔPbMAP1 parasite (Fig. 7A). The gene complemented parasite (ReΔPbMAP1) was cloned and verified using PCR with specific primers (Fig. 7B). Western blotting and IFA also confirmed PbMAP1 expression in the ReΔPbMAP1 strain (Fig. 7C, D).

Construction of the PbMAP1-complemented strain (ReΔPbMAP1). A Scheme of the transfection plasmid used to target and re-introduce PbMAP1 gene in ΔPbMAP1 using the CRISPR/Cas9 method. B PCR validation of PbMAP1 reintroduction. PCR products from 5′-UTR, 3′-UTR, and PbMAP1 showed that PbMAP1 was re-introduced. C Western blotting of PbMAP1 expression in ΔPbMAP1 and ReΔPbMAP1. No protein band with expected molecular weight was detected in the ΔPbMAP1 strain, but in the ReΔPbMAP1 strain; GAPDH was used as the control. D IFA using rat anti-PbMAP1 IgG to detect PbMAP1 expression. PbMAP1 was detected in WT and ReΔPbMAP1 but not in the ΔPbMAP1 strain

Deletion of PbMAP1 led to virulence deficiency

To investigate the correlation of the PbMAP1 with parasite infectivity, we infected mice with WT PbMAP1, ΔPbMAP1, or ReΔPbMAP1 at 1 × 106 parasites per mouse. Tail blood was analyzed daily post-infection using Giemsa-stained smears, which revealed that the degree of parasitemia in mice infected with the ΔPbMAP1 parasites was lower than that in mice infected with WT parasites. Moreover, the survival time of these mice was monitored. Mice infected with ΔPbMAP1 parasites died 4–10 days later than those infected with WT. All mice died of severe anemia (Fig. 8A, B). A similar phenomenon was noted in mice infected with WT, ΔPbMAP1, or ReΔPbMAP1 when infected with 1 × 103 or 1 × 104 parasites per mouse (Fig. 8C–F).

PbMAP1 deletion reduced the infectivity of PbMAP1. A and B Parasitemia and survival curves of BALB/c mice after intraperitoneal infection with 1 × 106 WT, ΔPbMAP1, or ReΔPbMAP1 parasites. C and D Parasitemia and survival curves of BALB/c mice after intraperitoneal infection with 1 × 104 WT, ΔPbMAP1, or ReΔPbMAP1 parasites. E and F Parasitemia in and survival curves of BALB/c mice after intraperitoneal infection with 1 × 103 WT, ΔPbMAP1, or ReΔPbMAP1 parasites.

Interestingly, as the parasites continued to divide and proliferate, their virulence appeared to recover. To confirm that the phenomenon of virulence recovery was the result of PbMAP1 knockout, qRT-PCR was performed on specific genes in the WT and ΔPbMAP1 parasites (Fig. 9A). Compared with WT, PbMAP1-knockout strains showed significantly upregulated transcript levels of MAEBL gene coding for the merozoite adhesive erythrocytic binding protein (MAEBL), and significantly downregulated transcript levels of 10 other genes, suggesting a complementary association between PbMAP1 and MAEBL. Western blotting showed that the expression level of the MAEBL protein in ΔPbMAP1 strains was higher than that in WT strains (Fig. 9B, C).

Transcription analysis of invasion-related genes in the ΔPbMAP1 parasites with qRT-PCR. A Transcription of MAEBL was significantly upregulated in ΔPbMAP1 strains compared to that in the wild-type strain. B and C Expression of MAEBL protein in ΔPbMAP1 strains was positively correlated with transcription levels. Experiments were repeated three times. Error bars represent SD

Infection with ΔPbMAP1 induced stronger IFN-γ and TNF-α responses in infected mice

To explore the impact of the PbMAP1 on the outcome of blood-stage infection, we infected mice with either WT- or ΔPbMAP1-infected RBCs at 1 × 104 parasites per mouse and characterized the early immune response in WT- or ΔPbMAP1-infected mice. We collected sera on days 3, 5, 7, 10, and 15 after infection and assayed the samples for expression of various cytokines and chemokines (Fig. 10A). The serum levels of IFN-γ were higher in ΔPbMAP1-infected mice than the peak levels in the WT-infected mice, and peak levels were recorded on day 7 after infection (Fig. 10B). Similarly, on day 7 after infection, the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 were higher in ΔPbMAP1-infected mice (Fig. 10C–E). Conversely, on day 7 after infection, the levels of MCP-1 and CCL4 were higher in WT-infected mice than in ΔPbMAP1-infected mice (Fig. 10F, G). Over the infection time, the levels of CCL4 became equivalent in the two groups and continued to increase until day 10 after infection. Similarly, IL-12p70 levels increased with the progression of infection, although no significant differences were noted between the two groups (Fig. 10H).

ΔPbMAP1 infection induced stronger IFN-γ and TNF-α responses in infected mice. A BALB/c mice were infected with either ΔPbMAP1 or WT using 1 × 104 iRBCs per mouse intraperitoneally. Parasitemia was monitored during the course of infection. Each circle represents an individual mouse. Analyses were performed with five animals per group. B–H Sera collected from infected mice at different time points. Time-dependent changes in serum levels of various cytokines and chemokines as quantified using a bead array (BD). Each circle refers to the response of a mouse, and lines indicate mean values. Statistically significant differences are shown with asterisks (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001)

Discussion

The invasion of Plasmodium into RBCs is a rapid and complex process that involves RBC adhesion, apical reorientation, mobile junction complex, and parasitophorous vacuole membrane (PVM) formation and modification in a series of dynamic steps [24,25,26]. The key proteins associated with RBC parasite invasion include various proteins located on the merozoite surface, in micronemes, rhoptries, and dense granules [27,28,29]. When a merozoite invades RBCs, the parasite’s surface proteins bind to RBC surface receptors, increasing calcium concentration in the cytoplasm of the parasite; this in turn stimulates the secretion of microneme proteins, such as TRAP, which plays an important role in the gliding motility and invasion, leading to a series of invasion steps [30,31,32,33,34]. Therefore, adhesion is the first step for Plasmodium to invade RBCs, and proteins located on the surface of merozoites play pivotal roles in the process of invasion. However, specific surface proteins that bind to RBCs have not been fully characterized, and these proteins may be important virulence factors in the process of infection.

Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) are long linear carbohydrate chains that are attached to the core proteins to form proteoglycans. HS is a GAG and comprises alternating glucosamine and uronic acid residues in the repeated disaccharide unit (-4GlcAβ1-4GlcNAcα1-) [6, 14, 35]. HS is localized to the cell surface and in the extracellular matrix of many tissues, and it is implicated in multiple aspects of the Plasmodium life cycle [36, 37]. As such, HS is the major receptor for Plasmodium invading RBCs [38,39,40,41].

Early studies reported that peptides that can bind to heparin contain one or more consistent heparin-binding motifs, namely [-X-B-B-X-B-X-] or [- X-B-B-B-X-X-B-X-], where B is the basic residue of basic amino acids, such as lysine, arginine, and histidine, and X is a hydrophilic amino acid residue [42]. Previous studies on P. falciparum indicated that the binding of PfEMP1 to HS receptor on RBCs relies on the presence of multiple heparin-binding motifs in the DBLα region [39]. In the present study, we identified a novel protein, PbMAP1, which contains heparin-binding motifs, indicating that PbMAP1 can potentially bind HS-like receptor. Therefore, the binding of PbMAP1 to the RBCs surface receptor was investigated.

Specifically, our IFA and electron microscopy demonstrated that PbMAP1 is expressed on the surface of P. berghei. As a surface protein, PbMAP1 may be involved in the interaction between the parasite and RBC surface receptors. Based on three-dimensional (3D) structural modeling of PbMAP1 and its heparin-binding motifs, we expressed and purified the recombinant protein GST-PbMAP1 in Escherichia coli and used the GST protein as the negative control for functional verification. Heparin-binding and competitive inhibition experiments showed that GST-PbMAP1 could bind to heparin in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2). IFA, western blotting, and flow cytometry further indicated that the PbMAP1 protein could bind to the surface of RBCs (Fig. 3). Therefore, PbMAP1 may be involved in binding to HS-like receptor on the RBC surface.

Furthermore, PbMAP1 was knocked out to assess its function. We found that the pathogenicity of the ΔPbMAP1 strain in mice was attenuated compared to that of the WT strain (Fig. 8). The use of PbMAP1-knockout strain further demonstrated the role of the PbMAP1 protein in the binding to RBCs. In addition, we observed that mice immunized with PbMAP1-specific peptides achieved immune protection (Fig. 5). Therefore, PbMAP1 may play important roles in the binding and invasion of P. berghei to RBCs. Interestingly, we found that with the continuous replication of the parasites, the infectivity of the ΔPbMAP1 parasite seemed recovered. Therefore, we speculated that some ways of compensation may occur. We collected WT and ΔPbMAP1 strains and searched for genes with significant differences in transcript levels after PbMAP1 knockout using qRT-PCR. The transcript level of MAEBL was surprisingly found significantly upregulated, but the transcript levels of 10 other merozoite genes were significantly downregulated. These results confirmed that PbMAP1 knockout affected MAEBL expression (Fig. 8).

To assess the potential mechanism through which injection with the ΔPbMAP1 strain can confer immune protection in mice, we examined changes in cytokine levels after immunizing with the ΔPbMAP1 strains. Levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10, which are important for the activation of protective immunity, were significantly increased at the early stage of ΔPbMAP1 infection. Therefore, PbMAP1 expression is likely beneficial to the parasite by preventing protective immune responses in the host.

Conclusion

The present study showed that the surface protein PbMAP1 is involved in the binding of P. berghei to the HS receptor on RBC surface. The absence of PbMAP1 is presumably deleterious to the parasite, as it evokes a specific immune response in the host. Our findings revealed the interaction between PbMAP1, a novel P. berghei surface protein, and HS-like receptor during invasion. Simultaneously, these findings can be useful approaches for deep characterization of P. falciparum proteins in human malaria.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional file.

Abbreviations

- RBCs:

-

Red blood cells

- PbANKA:

-

Plasmodium berghei ANKA

- HS:

-

Heparan sulfate

- GAGs:

-

Glycosaminoglycans

- MSP:

-

Merozoite surface protein

- EBL:

-

Erythrocyte binding antigens

- MAEBL:

-

Merozoite adhesive erythrocytic binding protein

- IP:

-

Intraperitoneal

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffer saline

- SDS-PAGE:

-

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- HS:

-

Heparan sulfate

- CSA:

-

Chondroitin sulfate A

- RPMI:

-

Roswell Park Memorial Institute

- DAPI:

-

2′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- IV:

-

Intravenous

- WT:

-

Wildtype

- IFN-γ:

-

Interferon gamma

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- MCP-1:

-

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- CCL4:

-

Macrophage inflammatory protein-1β

References

World Health Organization: World malaria report 2021. https://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2021/report/en/

Miller LH, Baruch DI, Marsh K, Doumbo OK. The pathogenic basis of malaria. Nature. 2002;415:673–9.

Gaur D, Mayer DCG, Miller LH. Parasite ligand–host receptor interactions during invasion of erythrocytes by Plasmodium merozoites. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:1413–29.

Gilson PR, Nebl T, Vukcevic D, Moritz RL, Sargeant T, Speed TP, et al. Identification and stoichiometry of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored membrane proteins of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1286–99.

Kobayashi K, Kato K, Sugi T, Yamane D, Shimojima M, Tohya Y, et al. Application of retrovirus-mediated expression cloning for receptor screening of a parasite. Anal Biochem. 2009;389:80–2.

Zimmermann R, Werner C, Sterling J. Exploring structure–property relationships of GAGs to tailor ECM-mimicking hydrogels. Polymers (Basel). 2018;10:1376.

Rasti N, Wahlgren M, Chen Q. Molecular aspects of malaria pathogenesis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;41:9–26.

Lima M, Rudd T, Yates E. New applications of heparin and other glycosaminoglycans. Molecules. 2017;22:749.

Vogt AM, Pettersson F, Moll K, Jonsson C, Normark J, Ribacke U, et al. Release of sequestered malaria parasites upon injection of a glycosaminoglycan. PloS Pathog. 2006;2:e100.

Carruthers VB, Håkansson S, Giddings OK, Sibley LD. Toxoplasma gondii uses sulfated proteoglycans for substrate and host cell attachment. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4005–11.

Boyle MJ, Richards JS, Gilson PR, Chai W, Beeson JG. Interactions with heparin-like molecules during erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. Blood. 2010;115:4559–68.

Azzouz N, Kamena F, Laurino P, Kikkeri R, Mercier C, Cesbron-Delauw M, et al. Toxoplasma gondii secretory proteins bind to sulfated heparin structures. Glycobiology. 2013;23:106–20.

Chen Q, Barragan A, Fernandez V, Sundström A, Schlichtherle M, Sahlén A, et al. Identification of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane proteins 1 (PfEMP1) as the rosetting ligand of the malaria parasite P. falciparum. J Exp Med. 1998;187:15–23.

Vogt AM, Barragan A, Chen Q, Kironde F, Spillmann D, Wahlgren M. Heparan sulfate on endothelial cells mediates the binding of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes via the DBL1alpha domain of PfEMP1. Blood. 2003;101:2405–11.

Kobayashi K, Kato K, Sugi T, Takemae H, Pandey K, Gong H, et al. Plasmodium falciparum BAEBL binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycans on the human erythrocyte surface. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:1716–25.

Baum J, Chen L, Healer J, Lopaticki S, Boyle M, Triglia T, et al. Reticulocyte-binding protein homologue 5 – an essential adhesin involved in invasion of human erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39:371–80.

**ao L, Yang C, Patterson PS, Udhayakumar V, Lal AA. Sulfated polyanions inhibit invasion of erythrocytes by plasmodial merozoites and cytoadherence of endothelial cells to parasitized erythrocytes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1373–8.

Sanni LA, Fonseca LF, Langhorne J. Mouse models for erythrocytic-stage malaria. Methods Mol Med. 2002;72:57–76.

Aurrecoechea C, Brestelli J, Brunk BP, Dommer J, Fischer S, Gajria B, et al. PlasmoDB: a functional genomic database for malaria parasites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D539-43.

Zhang D, Jiang N, Chen Q. ROP9, MIC3, and SAG2 are heparin-binding proteins in Toxoplasma gondii and involved in host cell attachment and invasion. Acta Trop. 2019;192:22–9.

Goel VK, Li X, Chen H, Liu S-C, Chishti AH, Oh SS. Band3 is a host receptor binding merozoite surface protein 1 during the Plasmodium falciparum invasion of erythrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5164–9.

Janse CJ, Ramesar J, Waters AP. High-efficiency transfection and drug selection of genetically transformed blood stages of the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:346–56.

Kyes S, Pinches R, Newbold C. A simple RNA analysis method shows var and rif multigene family expression patterns in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;105:311–5.

Gilson PR, Crabb BS. Morphology and kinetics of the three distinct phases of red blood cell invasion by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39:91–6.

Aikawa M, Miller LH, Johnson J, Rabbege J. Erythrocyte entry by malarial parasites. A moving junction between erythrocyte and parasite. J Cell Biol. 1978;77:72–82.

Cowman AF, Crabb BS. Invasion of red blood cells by malaria parasites. Cell. 2006;124:755–66.

Sam-Yellowe TY. Rhoptry organelles of the apicomplexa: their role in host cell invasion and intracellular survival. Parasitol Today. 1996;12:308–16.

Cowman AF, Tonkin CJ, Tham WH, Duraisingh MT. The molecular basis of erythrocyte invasion by malaria parasites. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22:232–45.

Zhao X, Chang Z, Tu Z, Yu S, Wei X, Zhou J, et al. PfRON3 is an erythrocyte-binding protein and a potential blood-stage vaccine candidate antigen. Malar J. 2014;13:490.

Sultan AA, Thathy V, Frevert U, Robson KJH, Crisanti A, Nussenzweig V, et al. TRAP is necessary for gliding motility and infectivity of plasmodium sporozoites. Cell. 1997;90:511–22.

Bargieri DY, Thiberge S, Tay CL, Carey AF, Rantz A, Hischen F, et al. Plasmodium merozoite TRAP family protein is essential for vacuole membrane disruption and gamete egress from erythrocytes. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:618–30.

Buscaglia CA, Coppens I, Hol WGJ, Nussenzweig V. Sites of interaction between aldolase and thrombospondin-related anonymous protein in plasmodium. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:4947–57.

Lovett JL, Sibley LD. Intracellular calcium stores in Toxoplasma gondii govern invasion of host cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3009–16.

Billker O, Lourido S, Sibley LD. Calcium-dependent signaling and kinases in apicomplexan parasites. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:612–22.

Dennissen MABA, Jenniskens GJ, Pieffers M, Versteeg EMM, Petitou M, Veerkamp JH, et al. Large, tissue-regulated domain diversity of heparan sulfates demonstrated by phage display antibodies. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10982–6.

McQuaid F, Rowe JA. Rosetting revisited: a critical look at the evidence for host erythrocyte receptors in Plasmodium falciparum rosetting. Parasitology. 2020;147:1–11.

Adams Y, Kuhnrae P, Higgins MK, Ghumra A, Rowe JA. Rosetting Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes bind to human brain microvascular endothelial cells in vitro, demonstrating a dual adhesion phenotype mediated by distinct P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 domains. Infect Immun. 2014;82:949–59.

Zhang Y, Jiang N, Lu H, Hou N, Piao X, Cai P, et al. Proteomic analysis of Plasmodium falciparum schizonts reveals heparin-binding merozoite proteins. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:2185–93.

Barragan A, Fernandez V, Chen Q, von Euler A, Wahlgren M, Spillmann D. The Duffy-binding-like domain 1 of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) is a heparan sulfate ligand that requires 12 mers for binding. Blood. 2000;95:3594–9.

Kobayashi K, Kato K. Evaluating the use of heparin for synchronization of in vitro culture of Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitol Int. 2016;65:549–51.

Weiss GE, Gilson PR, Taechalertpaisarn T, Tham WH, de Jong NWM, Harvey KL, et al. Revealing the sequence and resulting cellular morphology of receptor–ligand interactions during Plasmodium falciparum invasion of erythrocytes. PLOS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004670.

Cardin AD, Weintraub HJ. Molecular modeling of protein–glycosaminoglycan interactions. Arterioscler Dallas Tex. 1989;9:21–32.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Nature and Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82030060) and CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (grant no. 2019-I2M-5-042).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JG performed most experiments, analyzed that data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. NJ mentored all experimental work. YZ assisted with the parasite proliferation and bioinformatics analysis. RC assisted with the immunological analysis. YF assisted with the immunofluorescence experiments. XS assisted with the cell adhesion experiments. QC conceived the study, analyzed the data, and finalized the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal protocols and procedures were performed according to the regulations of the Animal Ethics Committee of the Shenyang Agricultural University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Primer sequences referred to in this study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, J., Jiang, N., Zhang, Y. et al. A heparin-binding protein of Plasmodium berghei is associated with merozoite invasion of erythrocytes. Parasites Vectors 16, 277 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-023-05896-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-023-05896-w