Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-engineered T cells (CAR-T cells) have yielded unprecedented efficacy in B cell malignancies, most remarkably in anti-CD19 CAR-T cells for B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) with up to a 90% complete remission rate. However, tumor antigen escape has emerged as a main challenge for the long-term disease control of this promising immunotherapy in B cell malignancies. In addition, this success has encountered significant hurdles in translation to solid tumors, and the safety of the on-target/off-tumor recognition of normal tissues is one of the main reasons. In this mini-review, we characterize some of the mechanisms for antigen loss relapse and new strategies to address this issue. In addition, we discuss some novel CAR designs that are being considered to enhance the safety of CAR-T cell therapy in solid tumors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

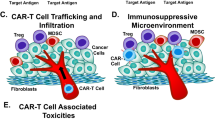

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) is a modular fusion protein comprising extracellular target binding domain usually derived from the single-chain variable fragment (scFv) of antibody, spacer domain, transmembrane domain, and intracellular signaling domain containing CD3z linked with zero or one or two costimulatory molecules such as CD28, CD137, and CD134 [1–3]. T cells engineered to express CAR by gene transfer technology are capable of specifically recognizing their target antigen through the scFv binding domain, resulting in T cell activation in a major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-independent manner [4]. In the past several years, clinical trials from several institutions to evaluate CAR-modified T cell (CAR-T cell) therapy for B cell malignancies including B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (B-NHL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) have demonstrated promising outcomes by targeting CD19 [5–13], CD20 [14], or CD30 [15], where mostly compelling success has been achieved in CD19-specific CAR-T cells for B-ALL with similar high complete remission (CR) rates of 70~94% [5–8, 12]. This significant efficacy not only leads to an impending paradigm shift in the treatment of B cell malignancies but also results in a strong push toward expanding the uses of CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors. However, the preliminary outcomes of clinical trials testing epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [16], mesothelin (MSLN) [17, 18], variant III of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFRvIII) [19], human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) [20, 21], carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) [22], and prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) [23] in solid tumors are less encouraging. Moreover, rapid death caused by the off-tumor cross-reaction of CAR-T cells has been reported [20], highlighting the important priority of enhancing CAR-T cell therapy safety. Overall, there remain several powerful challenges to the broad application of CAR-T cell therapy in the future: (1) antigen loss relapse, an emerging threat to CAR-T cell therapy, mainly observed in anti-CD19 CAR-T cells for B-ALL; (2) on-target/off-tumor toxicity resulting from the recognition of healthy tissues by CAR-T cells which can cause severe and even life-threatening toxicities, especially in the setting of solid tumors; (3) there is less efficacy in solid tumors, mainly due to the hostile tumor microenvironment; (4) difficulty of industrialization because of the personalized autologous T cell manufacturing and widely “distributed” approach. How to surmount these hurdles presents a principal direction of CAR-T cell therapy development, and a variety of strategies are now being investigated (Fig. 1). Here, we mainly focus on the new CAR design to address tumor antigen escape relapse and to enhance the safety of CAR-T cells in solid tumors.

Future directions in CAR-T cell therapy. Overcoming antigen loss relapse and enhancing efficacy and safety present a principal direction of CAR-T cell therapy optimization. “Off-the-shelf” CAR-T, a biologic that is pre-prepared in advance from one or more healthy unrelated donors, validated, and cryopreserved and then can be shipped to patients worldwide, is deemed to be the ultimate product formulation. CAR chimeric antigen receptor, CAR-T cell chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cell, B-ALL B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, B-NHL B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, CLL chronic lymphocytic leukemia, HL Hodgkin’s lymphoma, MM multiple myeloma, EGFR epidermal growth factor receptor, MSLN mesothelin, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor-2, EGFRvIII variant III of the epidermal growth factor receptor, PSMA prostate-specific membrane antigen, CEA carcinoembryonic antigen

How to overcome antigen loss relapse in hematological malignancies

Antigen escape rendering CAR-T cells ineffective against tumor cells is an emerging threat to CAR-T cell therapy, which has been mainly seen in the clinical trials involving CD19 in hematological malignancies. It appears to be most common in B-ALL and has been observed in approximately 14% of pediatric and adult responders across institutions (Table 1) [5, 24–26]. It has also been documented in CLL [27, 28] and primary mediastinal large B cell lymphoma (PMLBCL) [29]. Indeed, it has also been noted in patients who received blinatumomab [30], a first-in-class bispecific T engager (BiTE) antibody against CD19/CD3 [31, 32], which has also shown promising efficacy in B cell malignancies [33–35], implying that this specific escape may result from the selective pressure of CD19-directed T cell immunotherapy [36]. Moreover, tumor editing resulting from the selective pressure exerted by CAR-T cell therapy also can be seen when beyond CD19; we observed that a patient with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) experienced selected proliferation of leukemic cells with low saturation of CD33 expression under the persistent stress of CD33-directed CAR-T cells [37]. Actually, antigen escape has also been reported in the experimental study of solid tumor, where targeting HER2 in a glioblastoma cell line results in the emergence of HER2-null tumor cells that maintain the expression of non-targeted, tumor-associated antigens [38]. These findings suggest that treatment of patients with specifically targeted therapies such as CAR-T cell therapy always carry the risk of tumor editing, highlighting that development of approaches to preventing and treating antigen loss escapes would therefore represent a vertical advance in the field.

Given the extensive trials to date involving CD19, we have gained a much better understanding regarding possible mechanism of these phenomena. Although all these antigen escape relapses are characterized by the loss of detectable CD19 on the surface of tumor cells, multiple mechanisms are involved. One mechanism is that CD19 is still present but cannot be detected and recognized by anti-CD19 CAR-T cells as its cell surface fragment containing cognate epitope is absent because of deleterious mutation and alternative splicing. Sotillo and colleagues showed a CD19 isoform that skipped exon 2 (Δex2) characterized by the loss of the cognate CD19 epitope necessary for anti-CD19 CAR-T cells is strongly enriched compared to prior anti-CD19 CAR-T cell treatment in some patients with B-ALL who relapse after anti-CD19 CAR-T cell infusion. They estimated that this type of antigen escape relapse would occur in 10 to 20% of pediatric B-ALL treated with CD19-directed immunotherapy. Moreover, they found that this truncated isoform was more stable than full-length CD19 and partly rescued defects in cell proliferation and pre-B cell receptor (pre-BCR) signaling associated with CD19 loss [39]. Similar to that observed in B-ALL, a biopsy of renal lesion from a patient with persistent renal involvement by PMLBCL 2 months after anti-CD19 CAR-T cell infusion indicated that activated anti-CD19 CAR-T cells could infiltrate the tumor; however, the PMLBCL clone is absent on surface CD19 but shows positive cytoplasmic expression [29]. These findings imply that it may make sense to simultaneously evaluate the cytoplasmic and membranous expression of CD19 by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry. Moreover, leukemic lineage switch provides new insights into mechanisms of immune escape from targeted immunotherapy [40]. Gardner et al. reported on 2 of 7 patients with B-ALL harboring rearrangement of the mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) gene and achieving molecular CR after anti-CD19 CAR-T cell infusion develo** AML that was clonally related to their B-ALL within 1 month after anti-CD19 CAR-T cell infusion [41]. Both aforementioned phenomena can be recapitulated in a syngeneic murine model where mice bearing E2a:PBX1 leukemia are treated with murine anti-CD19 CAR-T cells [42]. Intriguingly, researchers demonstrated that earlier relapses maintained pre-B phenotype with isolated CD19 loss, whereas later relapses involved multiple phenotypic changes, including the loss of additional B cell markers. Moreover, B cell-associated transcripts and an increase in the expression of myeloid or T cell genes consistent with lineage switching were also confirmed in later relapses by unsupervised clustering of RNA sequencing, implying that lineage switching results from reprogramming rather than depletion of CD19 alone. Outgrowth of preexisting rare CD19-negative malignant cells as a consequence of immunoediting also can lead to B-ALL cells escape anti-CD19 CAR-T cells killing, which is described by Ruella et al. in research focusing on dual CD19 and CD123 CAR-T cells [43]. They showed the existence of rare CD19-negative CD123-positive cells at baseline in the samples from patients with B-ALL. These cells emerged after anti-CD19 CAR-T cell administration, which accounts for the CD19-negative relapse as CD19-CD123+ blasts carried the disease-associated genetic aberration and can lead to the reconstitution of the original B-ALL phenotype when those cells are injected into NOD/SCID/gamma (NSG)-chain-deficient mice. On this basis, researchers developed a dual CAR-expressing construct that combined CD19- and CD123-mediated T cell activation and proved that this dual antigen receptor can treat and prevent CD19-loss relapses in a clinically relevant preclinical model of CD19-negative leukemia escape. Similar phenomena have also been shown in CLL, in which CD19-negative escape variants were selected due to the treatment pressure exerted by anti-CD19 CAR-T cells, which also resulted in the transformation from CLL to plasmablastic lymphoma [28].

Novel strategies to offset tumor antigen loss relapse are mainly geared toward generating T cells capable of recognizing multiple antigens, in which dual-targeted CAR-T cells have been actively investigated in preclinical research and have two main patterns: modifying individual T cells with two distinct CAR molecules with two different binding domains (known as dual-signaling CAR) [38, 43] or with one CAR molecule containing two different binding domains in tandem (termed TanCAR) [44–46]. The prerequisite of the dual-targeted CAR, either dual-signaling CAR or TanCAR, is that either antigen input can trigger robust anti-tumor activity, which ensures that there is always another antigen input that can work well and control antigen loss relapse in the setting of one antigen escape. The concept is simple but is still a challenge in the context of limited choices of clinically validated antigens and the constraint of suitable epitope selection in the setting of TanCAR [47]. Besides CD19, other pan-B cell markers such as CD20 [14] and CD22 [36] can be proposed as a target for dual-targeted CAR in B cell malignancies as these antigen-directed CARs have been tested in humans and presented encouraging outcomes in early clinical trials. Moreover, CD123 (also called IL-3 receptor α chain) is also an ideal option for the target selection of dual-targeted CAR [43, 48]. It is worth noting that enhanced anti-tumor activity was demonstrated by dual-signaling CAR or TanCAR compared to the unispecific CAR or pooling unispecific CAR when both antigens are expressed on the tumor cell surface [43, 45], highlighting the safety concern. This design potentially increases the risk of CRS and on-target/off-tumor recognition resulting from more significant CAR-T cell expansion in vivo and cytokine release. In addition, whether the enhanced immune pressure directly caused by the enhanced anti-tumor activity can lead to loss of both antigens simultaneously because of tumor adaptation is another concern; hence, targeting two antigens may not be enough, and more studies are needed to determine the optimal antigen combination for each cancer. Other tactics to achieve dual recognition are pooling unispecific CAR-T cells; however, coadministering two CAR-T cell populations may result in the disproportionate expansion of one CAR-T cell suggested by the observation that anti-CD19 CAR-T cells have a significant growth advantage over CD20-specific CAR-T cells when in a coculture system, leading to a net decline in CD20-specific CAR-T cell count despite the presence of CD20 antigen [44]. Furthermore, sequentially infusing two groups of CAR-T cells [49] is also an alternative to avoid antigen escape and could circumvent the disproportionate expansion as seen in pooling CAR-T cells. However, it still is a combination of two groups of CAR-T cells as pooling CAR-T cells, resulting in a relatively long clinical time frame. Taken together, we would prefer dual-targeted CAR-T cells, but much additional work is needed to test and optimize this strategy before it can be translated into humans. Right now, our group are testing CD19/CD20 and CD19/CD22 dual-targeted CARs for B cell malignancies in experimental studies. Moreover, based on the lessons learned from the patient who received anti-CD33 CAR-T cells [37], a CD33/CD123 dual-targeted CAR for AML has already been included in our development pipeline.

On the other hand, selective targeting of cancer stem cells (CSCs) rather than tumor cells for CAR-T cell therapy may lead to better cancer treatment [50]. The reason for that is CSCs retain extensive self-renewal and tumorigenic potential, determining a tumor’s behavior, including proliferation and progression [51]. CD133 is an attractive therapeutic target for CAR-T cell therapy when targeting CSCs [52]. We first tested a CD133-directed CAR characterized by a shorted promoter in an effort to minimize the risk of on-target/off-tumor recognition in humans. A patient with cholangiocarcinoma, who progressed after anti-EGFR CAR-T cell therapy, in turn had another partial response with severe but can be managed epidermal/endothelial toxicities may due to the cross-reaction with CD133 expressed on normal epithelium and vascular endothelium after treated with CD133-directed CAR. These findings provide the proof-of-concept evidence that anti-CD133 CAR confers effective anti-tumor immunity which may contribute to the long-term disease control, but the on-target/off-tumor toxicity warrants further evaluation.

At the same time, some attention should be paid to the endogenous immune system, albeit it cannot be effective against tumor cells because of a lack of sufficient tumor-specific T cells as well as suppression by the tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment. By increasing cytokine production (e.g., IL-12) or the addition of immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., anti-PD-1/PD-L1/CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies), existing endogenous anti-tumor immune cells can be rescued and may even induce epitope spreading [53]. Epitope spreading is a process in which antigenic epitopes distinct from and non-cross-reactive with an inducing epitope become additional targets of an ongoing immune response [54], which provides the rationale for recruitment of endogenous immune cells to recognize and eradicate a new relapsed tumor clone. However, this hypothesis needs to be further verified in upcoming clinical trials. The most thorough reconstitution of the immune system is allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT), in which a patient’s own hematopoiesis is ablated through high-dose chemotherapy or radiation. Regenerated normal hematopoiesis including a new immune system can potentially recognize and destroy either type of tumor antigen escape relapse clone [36]. Significantly, allo-SCT is performed at several institutions for patients with B-ALL achieving CR after CAR-T cell therapy, and it demonstrated reduced relapse rate [25]. However, the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) group showed that among the 36 patients in CR following CAR-T cell infusion, 6-month overall survival (OS) did not differ significantly between patients who underwent allo-SCT (70%) and those who did not (64%) [55]. We suggest pursuit of consolidative allo-SCT for patients with B-ALL who achieve CR after CAR-T cell therapy regardless of the persistence of CAR-T cells in vivo, especially for patients who are thought to be at higher risk of relapse.

How to enhance safety of CAR-T cells in solid tumors

Severe treatment-related toxicities mainly due to the on-target/off-tumor recognition are another obstacle for CAR-T cell therapy beyond hematological malignancies [20]. How to abrogate the toxicity is crucial for this emerging technology and has become a research hotspot. Strategies for enhancing the safety of CAR-T cell therapy in solid tumors fall into several categories (Table 2).

Enhancing selectivity of CAR

Selecting safer antigen

CAR can only attack cells expressing targeted antigen; hence, the most direct and effective means to surmount off-tumor toxicities while not compromising efficacy is by targeting truly tumor-specific antigen expressed only on the tumor cells. However, the vast majority of CAR targets have been tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) that are overexpressed on tumor cells but also shared by normal “bystander” cells. Thus far, the only truly tumor-specific antigen for CAR is EGFRvIII, which is strictly confined to human cancer (most frequently observed in glioblastoma) [56]. An early outcome of EGFRvIII-specific CAR in 9 patients with EGFRvIII-positive glioblastoma demonstrated that the infusion was well-tolerated without off-tumor toxicities [19].

Of note, Posey et al. demonstrated that aberrantly glycosylated antigen-Tn-MUC1 can also be proposed as an ideal target for CAR-T cell therapy as selective recognition of Tn- and STn-positive malignant tumors has been achieved by T cells expressing 5E5 CAR, a newly designed CAR containing scFv derived from antibody 5E5 specific for Tn and STn glycoepitopes [57]. Moreover, robust cytotoxicity of 5E5 CAR-T cells in murine models of cancers as diverse as leukemia and pancreatic cancer also have been observed. Although much remains to be learned, these findings provide the proof-of-concept evidence that aberrantly glycosylated antigens can be proposed as a safer alternative than TAA for CAR-T cell therapy.

If we turn our attention from membrane surface molecules to the intracellular and/or secreted molecules, target selection becomes rich in diversity. Cancer/testis antigens (e.g., NY-ESO-1 and MAGE-A3) or differentiation antigens (e.g., gp100 and MART1) represent the most attractive targets for immunotherapy since these antigens are expressed only by tumor cells and spermatogenic cells from the testis or in a lineage-restricted manner [58]. However, antigens recognized by natural T cell receptor (TCR) through peptides/MHC engagement are invisible to conventional CAR as it can only recognize the membrane surface antigen. One intriguing strategy for expanding the antigenic repertoire to those antigens is using TCR-like antibody, an antibody directed to peptide-MHC (pMHC) complexes that can mimic the fine specificity of tumor recognition by TCR while having higher affinity than that of TCR [59]. T cells engineered to express the CAR comprising scFv derived from TCR-like antibody such as PR1/human leukocyte antigen (HLA-A2) or PR1/HLA-A2 alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)/HLA-A*02:01, gp100/HLA-A2 have been tested in vitro and in vivo [92]. This rapid onset of action resulted in the fast (within 24 h) and permanent abrogation of GVHD, albeit there remained a small number of residual iCasp9-modified T cells. Currently, several clinical trials evaluating iCasp9-modified CAR-T cells are enrolling patients (NCT02274584 and NCT02414269); however, these residual cell populations and the possibility of iCasp9 dimerization independent of dimerizing agent potentially limit the widespread use of this strategy [93]. This selective depletion can also be mediated by the clinically approved therapeutic antibody when the transduced cells are engineered to express the antibody targeted cell surface antigen such as truncated EGFR (tEGFR) [94], a human EGFR polypeptide retaining the intact cetuximab binding site in extracellular domain III. Moreover, tEGFR can serve as a cell surface marker for the identification of the infused CAR-T cells in vivo and has been used in clinical trials [5, 9]. Nonetheless, whether this cell ablation through antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity can rapidly start in the event that severe toxicity occurs in humans remains undetermined and needs to be verified in forthcoming clinical trials.

Conclusions

CAR-T cells are the best-in-class example of genetic engineering of T cells, bringing us spectacular opportunities and hopefully entering the mainstream of cancer therapy for B cell malignancies in the next 1–2 years. But tumor antigen escape relapse resulting from selective immune pressure of CAR-T cells highlights the shortcomings of this novel modality. Moreover, a similar surprise has not been elicited in the application of solid tumors with less efficacy and on-target/off-tumor toxicity, suggesting that enhancing the efficacy and safety of CAR-T cells should be considered as a starting point for the novel CAR design. Encouragingly, the proof-of-concept designs mentioned above to address these issues have been tested in experimental studies, providing preliminary evidence of feasibility and paving the road to further optimization. Of these designs, targeting more than one tumor antigen (i.e., dual-targeted CAR) should take the front seat due to it is not only beneficial to reducing or preventing the risk of antigen escape relapse either in hematological malignancies or solid tumors but also may alleviate the impact of antigenic heterogeneity on therapeutic effect in solid tumors. However, the prerequisite of the dual-targeted CAR for successfully offsetting antigen escape relapse is that it can effectively kill targets expressing either antigen, similarly to a monospecific CAR. This places a significant restriction on the implement in solid tumors as dual-targeted CAR potentially enhances the risk of on-target/off-tumor recognition compared to the unispecific CAR. In fact, as discussed above, the concept of using more than one target for CAR-T cell therapy in solid tumors mainly focuses on enhancing the specificity of CAR through the design of combinatorial antigen targeting, by which T cell only can be fully activated when the two target antigens are present at the same time. Above all, dual-targeted CAR is an optimal approach for overcoming antigen escape relapse with manageable on-target/off-tumor toxicity-B cell aplasia in B cell malignancies; however, it is still challenging to implement in solid tumors because it is difficult to balance the therapeutic effect and on-target/off-tumor toxicity. Combination tuning the sensitivity of CAR by scFv affinity with suicide gene may be a powerful strategy for broadening the application of dual-targeted CAR beyond hematological malignancies. However, the eventual effects of these novel designs still need to be determined in forthcoming clinical trials.

Abbreviations

- AFP:

-

Alpha-fetoprotein

- allo-SCT:

-

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation

- AML:

-

Acute myeloid leukemia

- B-ALL:

-

B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- BiTE:

-

Bispecific T engager

- B-NHL:

-

B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- CAR:

-

Chimeric antigen receptor

- CAR-T cells:

-

Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells

- CCR:

-

Chimeric costimulatory receptor

- CEA:

-

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- CLL:

-

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- CR:

-

Complete remission

- CSCs:

-

Cancer stem cells

- DLI:

-

Donor lymphocyte infusion

- EGFR:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- EGFRvIII:

-

Variant III of the epidermal growth factor receptor

- FITC:

-

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- GFP:

-

Green fluorescent protein

- GVHD:

-

Graft-versus-host disease

- GVT:

-

Graft versus tumor

- HER2:

-

Human epidermal growth factor receptor-2

- HL:

-

Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- HLA:

-

Human leukocyte antigen

- iCasp9:

-

Inducible caspase-9

- MHC:

-

Major histocompatibility complex

- MLL:

-

Mixed lineage leukemia

- MSKCC:

-

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

- MSLN:

-

Mesothelin

- NSG:

-

NOD/SCID/gamma-chain-deficient

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- pMHC:

-

Peptide-MHC

- PMLBCL:

-

Primary mediastinal large B cell lymphoma

- PNE:

-

Peptide neo-epitope

- pre-BCR:

-

Pre-B cell receptor

- Pro-antibody:

-

Protease-activated antibody

- PSCA:

-

Prostate stem cell antigen

- PSMA:

-

Prostate-specific membrane antigen

- scFv:

-

Single-chain variable fragment

- SynNotch:

-

Synthetic Notch receptors

- TAA:

-

Tumor associate antigen

- TCR:

-

T cell receptor

- tEGFR:

-

Truncated EGFR

- Upenn:

-

University of Pennsylvania

References

Eshhar Z. The T-body approach: redirecting T cells with antibody specificity. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;181:329–42.

Curran KJ, Pegram HJ, Brentjens RJ. Chimeric antigen receptors for T cell immunotherapy: current understanding and future directions. J Gene Med. 2012;14(6):405–15.

Dai H, Wang Y, Lu X, Han W. Chimeric antigen receptors modified T-cells for cancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(7):djv439.

Eshhar Z, Waks T, Gross G, Schindler DG. Specific activation and targeting of cytotoxic lymphocytes through chimeric single chains consisting of antibody-binding domains and the gamma or zeta subunits of the immunoglobulin and T-cell receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(2):720–4.

Turtle CJ, Hanafi LA, Berger C, Gooley TA, Cherian S, Hudecek M, Sommermeyer D, Melville K, Pender B, Budiarto TM, et al. CD19 CAR-T cells of defined CD4+:CD8+ composition in adult B cell ALL patients. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(6):2123–38.

Lee DW, Kochenderfer JN, Stetler-Stevenson M, Cui YK, Delbrook C, Feldman SA, Fry TJ, Orentas R, Sabatino M, Shah NN, et al. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet (London, England). 2015;385(9967):517–28.

Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, Aplenc R, Barrett DM, Bunin NJ, Chew A, Gonzalez VE, Zheng Z, Lacey SF, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(16):1507–17.

Davila ML, Riviere I, Wang X, Bartido S, Park J, Curran K, Chung SS, Stefanski J, Borquez-Ojeda O, Olszewska M, et al. Efficacy and toxicity management of 19-28z CAR T cell therapy in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(224):224ra225.

Turtle CJ, Hanafi LA, Berger C, Hudecek M, Pender B, Robinson E, Hawkins R, Chaney C, Cherian S, Chen X, et al. Immunotherapy of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with a defined ratio of CD8+ and CD4+ CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(355):355ra116.

Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, Kassim SH, Somerville RP, Carpenter RO, Stetler-Stevenson M, Yang JC, Phan GQ, Hughes MS, Sherry RM, et al. Chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and indolent B-cell malignancies can be effectively treated with autologous T cells expressing an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(6):540–9.

Kalos M, Levine BL, Porter DL, Katz S, Grupp SA, Bagg A, June CH. T cells with chimeric antigen receptors have potent antitumor effects and can establish memory in patients with advanced leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(95):95ra73.

Grupp SA, Maude SL, Shaw PA, Aplenc R, Barrett DM, Callahan C, Lacey SF, Levine BL, Melenhorst JJ, Motley L, et al. Durable remissions in children with relapsed/refractory ALL treated with T cells engineered with a CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor (CTL019). Blood. 2015;126(23):681.

Cai B, Guo M, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Yang J, Guo Y, Dai H, Yu C, Sun Q, Qiao J, et al. Co-infusion of haplo-identical CD19-chimeric antigen receptor T cells and stem cells achieved full donor engraftment in refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9(1):131.

Zhang W-y, Wang Y, Guo Y-l, Dai H, Yang Q-m, Zhang Y-j, Zhang Y, Chen M-x, Wang C-m, Feng K-c, et al. Treatment of CD20-directed chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: an early phase IIa trial report. Signal Transduction TargetTher. 2016;1:16002.

Wang CM, Wu ZQ, Wang Y, Guo YL, Dai HR, Wang XH, Li X, Zhang YJ, Zhang WY, Chen MX, et al. Autologous T Cells expressing CD30 chimeric antigen receptors for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: an open-label phase I trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2016. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1365.

Feng K, Guo Y, Dai H, Wang Y, Li X, Jia H, Han W. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for the immunotherapy of patients with EGFR-expressing advanced relapsed/refractory non-small cell lung cancer. Sci China Life Sci. 2016;59(5):468–79.

Beatty GL, Haas AR, Maus MV, Torigian DA, Soulen MC, Plesa G, Chew A, Zhao Y, Levine BL, Albelda SM, et al. Mesothelin-specific chimeric antigen receptor mRNA-engineered T cells induce anti-tumor activity in solid malignancies. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2(2):112–20.

Maus MV, Haas AR, Beatty GL, Albelda SM, Levine BL, Liu X, Zhao Y, Kalos M, June CH. T cells expressing chimeric antigen receptors can cause anaphylaxis in humans. Cancer Immunol Res. 2013;1(1):26–31.

O’Rourke DM, Nasrallah M, Morrissette JJ, Melenhorst JJ, Lacey SF, Mansfield K, Martinez-Lage M, Desai AS, Brem S, Maloney E, et al. Pilot study of T cells redirected to EGFRvIII with a chimeric antigen receptor in patients with EGFRvIII+ glioblastoma. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2016;34(15_suppl):2067.

Morgan RA, Yang JC, Kitano M, Dudley ME, Laurencot CM, Rosenberg SA. Case report of a serious adverse event following the administration of T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor recognizing ERBB2. Mol Ther. 2010;18(4):843–51.

Ahmed N, Brawley VS, Hegde M, Robertson C, Ghazi A, Gerken C, Liu E, Dakhova O, Ashoori A, Corder A, et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)—specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for the immunotherapy of HER2-positive sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(15):1688–96.

Katz SC, Burga RA, McCormack E, Wang LJ, Mooring W, Point GR, Khare PD, Thorn M, Ma Q, Stainken BF, et al. Phase I hepatic immunotherapy for metastases study of intra-arterial chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cell therapy for CEA+ liver metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(14):3149–59.

Slovin SF, Wang X, Borquez-Ojeda O, Stefanski J, Olszewska M, Taylor C, Bartido S, Scher HI, Sadelain M, Riviere I. Targeting castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) with autologous PSMA-directed CAR+ T cells. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2012;30(15_suppl):TPS4700.

Maude SL, Teachey DT, Rheingold SR, Shaw PA, Aplenc R, Barrett DM, Barker CS, Callahan C, Frey NV, Nazimuddin F, et al. Sustained remissions with CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cells in children with relapsed/refractory ALL. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2016;34(15_suppl):3011.

Lee DW, Stetler-Stevenson M, Yuan CM, Fry TJ, Shah NN, Delbrook C, Yates B, Zhang H, Zhang L, Kochenderfer JN, et al. Safety and response of incorporating CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy in typical salvage regimens for children and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2015;126(23):684.

Park JH, Riviere I, Wang X, Bernal Y, Purdon T, Halton E, Curran KJ, Sauter CS, Sadelain M, Brentjens RJ. Efficacy and safety of CD19-targeted 19-28z CAR modified T cells in adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-ALL. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(15_suppl):7010.

Pegram HJ, Smith EL, Rafiq S, Brentjens RJ. CAR therapy for hematological cancers: can success seen in the treatment of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia be applied to other hematological malignancies? Immunotherapy. 2015;7(5):545–61.

Evans AG, Rothberg PG, Burack WR, Huntington SF, Porter DL, Friedberg JW, Liesveld JL. Evolution to plasmablastic lymphoma evades CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Br J Haematol. 2015. doi:10.1111/bjh.13562.

Yu H, Sotillo E, Harrington C, Wertheim G, Paessler M, Maude SL, Rheingold SR, Grupp SA, Thomas-Tikhonenko A, Pillai V. Repeated loss of target surface antigen after immunotherapy in primary mediastinal large B cell lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2017;92(1):E11–3.

Yannakou CK, Came N, Bajel AR, Juneja S. CD19 negative relapse in B-ALL treated with blinatumomab therapy: avoiding the trap. Blood. 2015;126:4983.

Fan G, Wang Z, Hao M, Li J. Bispecific antibodies and their applications. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:130.

Kohnke T, Krupka C, Tischer J, Knosel T, Subklewe M. Increase of PD-L1 expressing B-precursor ALL cells in a patient resistant to the CD19/CD3-bispecific T cell engager antibody blinatumomab. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:111.

Fan D, Li W, Yang Y, Zhang X, Zhang Q, Yan Y, Yang M, Wang J, **ong D. Redirection of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes via an anti-CD3 × anti-CD19 bi-specific antibody combined with cytosine arabinoside and the efficient lysis of patient-derived B-ALL cells. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:108.

Linder K, Gandhiraj D, Hanmantgad M, Seiter K, Liu D. Complete remission after single agent blinatumomab in a patient with pre-B acute lymphoid leukemia relapsed and refractory to three prior regimens: hyperCVAD, high dose cytarabine mitoxantrone and CLAG. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2015;5:20.

Wu J, Fu J, Zhang M, Liu D. Blinatumomab: a bispecific T cell engager (BiTE) antibody against CD19/CD3 for refractory acute lymphoid leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:104.

Ruella M, Maus MV. Catch me if you can: leukemia escape after CD19-directed T cell immunotherapies. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2016;14:357–62.

Wang QS, Wang Y, Lv HY, Han QW, Fan H, Guo B, Wang LL, Han WD. Treatment of CD33-directed chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in one patient with relapsed and refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Mol Ther. 2015;23(1):184–91.

Hegde M, Corder A, Chow KK, Mukherjee M, Ashoori A, Kew Y, Zhang YJ, Baskin DS, Merchant FA, Brawley VS, et al. Combinational targeting offsets antigen escape and enhances effector functions of adoptively transferred T cells in glioblastoma. Mol Ther. 2013;21(11):2087–101.

Sotillo E, Barrett DM, Black KL, Bagashev A, Oldridge D, Wu G, Sussman R, Lanauze C, Ruella M, Gazzara MR, et al. Convergence of acquired mutations and alternative splicing of CD19 enables resistance to CART-19 immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(12):1282–95.

Perna F, Sadelain M. Myeloid leukemia switch as immune escape from CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) therapy. Transl Cancer Res. 2016;5(S2):S221–5.

Gardner R, Wu D, Cherian S, Fang M, Hanafi LA, Finney O, Smithers H, Jensen MC, Riddell SR, Maloney DG, et al. Acquisition of a CD19 negative myeloid phenotype allows immune escape of MLL-rearranged B-ALL from CD19 CAR-T cell therapy. Blood. 2016;127(20):2406–10.

Jacoby E, Nguyen SM, Fountaine TJ, Welp K, Gryder B, Qin H, Yang Y, Chien CD, Seif AE, Lei H, et al. CD19 CAR immune pressure induces B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia lineage switch exposing inherent leukaemic plasticity. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12320.

Ruella M, Barrett DM, Kenderian SS, Shestova O, Hofmann TJ, Perazzelli J, Klichinsky M, Aikawa V, Nazimuddin F, Kozlowski M, et al. Dual CD19 and CD123 targeting prevents antigen-loss relapses after CD19-directed immunotherapies. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(10):3814–26.

Zah E, Lin MY, Silva-Benedict A, Jensen MC, Chen YY. T cells expressing CD19/CD20 bi-specific chimeric antigen receptors prevent antigen escape by malignant B cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0231.

Hegde M, Mukherjee M, Grada Z, Pignata A, Landi D, Navai SA, Wakefield A, Fousek K, Bielamowicz K, Chow KK, et al. Tandem CAR T cells targeting HER2 and IL13Ralpha2 mitigate tumor antigen escape. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(8):3036–52.

Grada Z, Hegde M, Byrd T, Shaffer DR, Ghazi A, Brawley VS, Corder A, Schonfeld K, Koch J, Dotti G, et al. TanCAR: a novel bispecific chimeric antigen receptor for cancer immunotherapy. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2013;2:e105.

Sadelain M. Tales of antigen evasion from CAR therapy. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4(6):473.

Fan D, Li Z, Zhang X, Yang Y, Yuan X, Zhang X, Yang M, Zhang Y, **ong D. AntiCD3Fv fused to human interleukin-3 deletion variant redirected T cells against human acute myeloid leukemic stem cells. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:18.

Feng KC, Guo YL, Liu Y, Dai HR, Wang Y, Lv HY, Huang JH, Yang QM, Han WD. Cocktail treatment with EGFR-specific and CD133-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in a patient with advanced cholangiocarcinoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):4.

Ning N, Pan Q, Zheng F, Teitz-Tennenbaum S, Egenti M, Yet J, Li M, Ginestier C, Wicha MS, Moyer JS, et al. Cancer stem cell vaccination confers significant antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2012;72(7):1853–64.

Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414(6859):105–11.

Hermann PC, Bhaskar S, Cioffi M, Heeschen C. Cancer stem cells in solid tumors. Semin Cancer Biol. 2010;20(2):77–84.

Jackson HJ, Brentjens RJ. Overcoming antigen escape with CAR T-cell therapy. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(12):1238–40.

Ribas A, Timmerman JM, Butterfield LH, Economou JS. Determinant spreading and tumor responses after peptide-based cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2003;24(2):58–61.

Park JH, Riviere I, Wang X, Bernal Y, Purdon T, Halton E, Wang Y, Curran KJ, Sauter CS, Sadelain M, et al. Implications of minimal residual disease negative complete remission (MRD-CR) and allogeneic stem cell transplant on safety and clinical outcome of CD19-targeted 19-28z CAR modified T cells in adult patients with relapsed, refractory B-cell ALL. Blood. 2015;126(23):682.

Li G, Wong AJ. EGF receptor variant III as a target antigen for tumor immunotherapy. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7(7):977–85.

Posey Jr AD, Schwab RD, Boesteanu AC, Steentoft C, Mandel U, Engels B, Stone JD, Madsen TD, Schreiber K, Haines KM, et al. Engineered CAR T cells targeting the cancer-associated Tn-glycoform of the membrane mucin MUC1 control adenocarcinoma. Immunity. 2016;44(6):1444–54.

Noy R, Eppel M, Haus-Cohen M, Klechevsky E, Mekler O, Michaeli Y, Denkberg G, Reiter Y. T-cell receptor-like antibodies: novel reagents for clinical cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2005;5(3):523–36.

Dahan R, Reiter Y. T-cell-receptor-like antibodies—generation, function and applications. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2012;14:e6.

Liu H, Xu Y, **ang J, Long L, Green S, Yang Z, Zimdahl B, Lu J, Cheng N, Horan LH, et al. Targeting alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)-MHC complex with CAR T cell therapy for liver cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1203.

Ma Q, Garber HR, Lu S, He H, Tallis E, Ding X, Sergeeva A, Wood MS, Dotti G, Salvado B, et al. A novel TCR-like CAR with specificity for PR1/HLA-A2 effectively targets myeloid leukemia in vitro when expressed in human adult peripheral blood and cord blood T cells. Cytotherapy. 2016;18(8):985–94.

Zhang G, Wang L, Cui H, Wang X, Zhang G, Ma J, Han H, He W, Wang W, Zhao Y, et al. Anti-melanoma activity of T cells redirected with a TCR-like chimeric antigen receptor. Sci Rep. 2014;4:3571.

Gross G, Eshhar Z. Therapeutic potential of T cell chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) in cancer treatment: counteracting off-tumor toxicities for safe CAR T cell therapy. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;56:59–83.

Wilkie S, van Schalkwyk MC, Hobbs S, Davies DM, van der Stegen SJ, Pereira AC, Burbridge SE, Box C, Eccles SA, Maher J. Dual targeting of ErbB2 and MUC1 in breast cancer using chimeric antigen receptors engineered to provide complementary signaling. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32(5):1059–70.

Kloss CC, Condomines M, Cartellieri M, Bachmann M, Sadelain M. Combinatorial antigen recognition with balanced signaling promotes selective tumor eradication by engineered T cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(1):71–5.

Hanada K, Restifo NP. Double or nothing on cancer immunotherapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(1):33–4.

Morsut L, Roybal KT, **ong X, Gordley RM, Coyle SM, Thomson M, Lim WA. Engineering customized cell sensing and response behaviors using synthetic notch receptors. Cell. 2016;164(4):780–91.

Roybal KT, Rupp LJ, Morsut L, Walker WJ, McNally KA, Park JS, Lim WA. Precision tumor recognition by T cells with combinatorial antigen-sensing circuits. Cell. 2016;164(4):770–9.

Blankenstein T. Receptor combinations hone T-cell therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34(4):389–91.

Fedorov VD, Themeli M, Sadelain M. PD-1- and CTLA-4-based inhibitory chimeric antigen receptors (iCARs) divert off-target immunotherapy responses. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(215):215ra172.

Tan MP, Gerry AB, Brewer JE, Melchiori L, Bridgeman JS, Bennett AD, Pumphrey NJ, Jakobsen BK, Price DA, Ladell K, et al. T cell receptor binding affinity governs the functional profile of cancer-specific CD8+ T cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015;180(2):255–70.

Zhong S, Malecek K, Johnson LA, Yu Z, Vega-Saenz de Miera E, Darvishian F, McGary K, Huang K, Boyer J, Corse E, et al. T-cell receptor affinity and avidity defines antitumor response and autoimmunity in T-cell immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(17):6973–8.

Chmielewski M, Hombach A, Heuser C, Adams GP, Abken H. T cell activation by antibody-like immunoreceptors: increase in affinity of the single-chain fragment domain above threshold does not increase T cell activation against antigen-positive target cells but decreases selectivity. J Immunol. 2004;173(12):7647–53.

Caruso HG, Hurton LV, Najjar A, Rushworth D, Ang S, Olivares S, Mi T, Switzer K, Singh H, Huls H, et al. Tuning sensitivity of CAR to EGFR density limits recognition of normal tissue while maintaining potent antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 2015;75(17):3505–18.

Liu X, Jiang S, Fang C, Yang S, Olalere D, Pequignot EC, Cogdill AP, Li N, Ramones M, Granda B, et al. Affinity-tuned ErbB2 or EGFR chimeric antigen receptor T cells exhibit an increased therapeutic index against tumors in mice. Cancer Res. 2015;75(17):3596–607.

Harris DT, Kranz DM. Adoptive T cell therapies: a comparison of T cell receptors and chimeric antigen receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2016;37(3):220–30.

Erster O, Thomas JM, Hamzah J, Jabaiah AM, Getz JA, Schoep TD, Hall SS, Ruoslahti E, Daugherty PS. Site-specific targeting of antibody activity in vivo mediated by disease-associated proteases. J Control Release. 2012;161(3):804–12.

Desnoyers LR, Vasiljeva O, Richardson JH, Yang A, Menendez EE, Liang TW, Wong C, Bessette PH, Kamath K, Moore SJ, et al. Tumor-specific activation of an EGFR-targeting probody enhances therapeutic index. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(207):207ra144.

Klebanoff CA, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Prospects for gene-engineered T cell immunotherapy for solid cancers. Nat Med. 2016;22(1):26–36.

Gill S, June CH. Going viral: chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for hematological malignancies. Immunol Rev. 2015;263(1):68–89.

Zhao Y, Moon E, Carpenito C, Paulos CM, Liu X, Brennan AL, Chew A, Carroll RG, Scholler J, Levine BL, et al. Multiple injections of electroporated autologous T cells expressing a chimeric antigen receptor mediate regression of human disseminated tumor. Cancer Res. 2010;70(22):9053–61.

Barrett DM, Zhao Y, Liu X, Jiang S, Carpenito C, Kalos M, Carroll RG, June CH, Grupp SA. Treatment of advanced leukemia in mice with mRNA engineered T cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22(12):1575–86.

Tanyi JL, Haas AR, Beatty GL, Morgan MA, Stashwick CJ, O’Hara MH, Porter DL, Maus MV, Levine BL, Lacey SF, et al. Abstract CT105: Safety and feasibility of chimeric antigen receptor modified T cells directed against mesothelin (CART-meso) in patients with mesothelin expressing cancers. Cancer Res. 2015;75(15 Supplement):CT105.

Juillerat A, Marechal A, Filhol JM, Valton J, Duclert A, Poirot L, Duchateau P. Design of chimeric antigen receptors with integrated controllable transient functions. Sci Rep. 2016;6:18950.

Wu CY, Roybal KT, Puchner EM, Onuffer J, Lim WA. Remote control of therapeutic T cells through a small molecule-gated chimeric receptor. Science. 2015;350(6258):aab4077.

Cao Y, Rodgers DT, Du J, Ahmad I, Hampton EN, Ma JS, Mazagova M, Choi SH, Yun HY, **ao H, et al. Design of switchable chimeric antigen receptor T cells targeting breast cancer. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55(26):7520–4.

Kim MS, Ma JS, Yun H, Cao Y, Kim JY, Chi V, Wang D, Woods A, Sherwood L, Caballero D, et al. Redirection of genetically engineered CAR-T cells using bifunctional small molecules. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(8):2832–5.

Ma JS, Kim JY, Kazane SA, Choi SH, Yun HY, Kim MS, Rodgers DT, Pugh HM, Singer O, Sun SB, et al. Versatile strategy for controlling the specificity and activity of engineered T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(4):E450–8.

Liu K, Liu X, Peng Z, Sun H, Zhang M, Zhang J, Liu S, Hao L, Lu G, Zheng K, et al. Retargeted human avidin-CAR T cells for adoptive immunotherapy of EGFRvIII expressing gliomas and their evaluation via optical imaging. Oncotarget. 2015;6(27):23735–47.

Rodgers DT, Mazagova M, Hampton EN, Cao Y, Ramadoss NS, Hardy IR, Schulman A, Du J, Wang F, Singer O, et al. Switch-mediated activation and retargeting of CAR-T cells for B-cell malignancies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(4):E459–68.

Jones BS, Lamb LS, Goldman F, Di Stasi A. Improving the safety of cell therapy products by suicide gene transfer. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:254.

Di Stasi A, Tey SK, Dotti G, Fujita Y, Kennedy-Nasser A, Martinez C, Straathof K, Liu E, Durett AG, Grilley B, et al. Inducible apoptosis as a safety switch for adoptive cell therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(18):1673–83.

Bonifant CL, Jackson HJ, Brentjens RJ, Curran KJ. Toxicity and management in CAR T-cell therapy. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2016;3:16011.

Wang X, Chang WC, Wong CW, Colcher D, Sherman M, Ostberg JR, Forman SJ, Riddell SR, Jensen MC. A transgene-encoded cell surface polypeptide for selection, in vivo tracking, and ablation of engineered cells. Blood. 2011;118(5):1255–63.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This research was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81230061 to WDH), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Bei**g City (No. Z151100003915076 to WDH), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2016YFC1303501 and 2016YFC1303504 to WDH).

Availability of data and materials

The material supporting the conclusion of this review has been included within the article.

Authors’ contributions

WH designed the study. ZWa drafted the manuscript. ZWu and YL participated in the manuscript preparation and revisions. ZWa designed and finalized the figure and tables. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

This is not applicable for this review.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is not applicable for this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Wu, Z., Liu, Y. et al. New development in CAR-T cell therapy. J Hematol Oncol 10, 53 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-017-0423-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-017-0423-1