Abstract

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic affects maternal health both directly and indirectly, and direct and indirect effects are intertwined. To provide a comprehensive overview on this broad topic in a rapid format behooving an emergent pandemic we conducted a sco** review.

Methods

A sco** review was conducted to compile evidence on direct and indirect impacts of the pandemic on maternal health and provide an overview of the most significant outcomes thus far. Working papers and news articles were considered appropriate evidence along with peer-reviewed publications in order to capture rapidly evolving updates. Literature in English published from January 1st to September 11 2020 was included if it pertained to the direct or indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the physical, mental, economic, or social health and wellbeing of pregnant people. Narrative descriptions were written about subject areas for which the authors found the most evidence.

Results

The search yielded 396 publications, of which 95 were included. Pregnant individuals were found to be at a heightened risk of more severe symptoms than people who are not pregnant. Intrauterine, vertical, and breastmilk transmission were unlikely. Labor, delivery, and breastfeeding guidelines for COVID-19 positive patients varied. Severe increases in maternal mental health issues, such as clinically relevant anxiety and depression, were reported. Domestic violence appeared to spike. Prenatal care visits decreased, healthcare infrastructure was strained, and potentially harmful policies implemented with little evidence. Women were more likely to lose their income due to the pandemic than men, and working mothers struggled with increased childcare demands.

Conclusion

Pregnant women and mothers were not found to be at higher risk for COVID-19 infection than people who are not pregnant, however pregnant people with symptomatic COVID-19 may experience more adverse outcomes compared to non-pregnant people and seem to face disproportionate adverse socio-economic consequences. High income and low- and middle-income countries alike faced significant struggles. Further resources should be directed towards quality epidemiological studies.

Plain English summary

The Covid-19 pandemic impacts reproductive and perinatal health both directly through infection itself but also indirectly as a consequence of changes in health care, social policy, or social and economic circumstances. The direct and indirect consequences of COVID-19 on maternal health are intertwined. To provide a comprehensive overview on this broad topic we conducted a sco** review. Pregnant women who have symptomatic COVID-19 may experience more severe outcomes than people who are not pregnant. Intrauterine and breastmilk transmission, and the passage of the virus from mother to baby during delivery are unlikely. The guidelines for labor, delivery, and breastfeeding for COVID-19 positive patients vary, and this variability could create uncertainty and unnecessary harm. Prenatal care visits decreased, healthcare infrastructure was strained, and potentially harmful policies are implemented with little evidence in high and low/middle income countries. The social and economic impact of COVID-19 on maternal health is marked. A high frequency of maternal mental health problems, such as clinically relevant anxiety and depression, during the epidemic are reported in many countries. This likely reflects an increase in problems, but studies demonstrating a true change are lacking. Domestic violence appeared to spike. Women were more vulnerable to losing their income due to the pandemic than men, and working mothers struggled with increased childcare demands. We make several recommendations: more resources should be directed to epidemiological studies, health and social services for pregnant women and mothers should not be diminished, and more focus on maternal mental health during the epidemic is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

COVID-19, first documented in Wuhan, China at the end of 2019 [1], has rapidly spread across the globe, infecting tens of millions of individuals [2]. While sex-disaggregated data on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) mortalities suggest it poses more severe health outcomes for men than women [3], there are concerns that the disease could disproportionately burden women in a social and economic sense. Furthermore, it is a particularly salient question whether pregnant women are more susceptible to infection with SARS-CoV-2 or have more severe disease outcomes. Outside of direct infection, the impact of the pandemic and pandemic-control policies on healthcare infrastructure, societies, and the global economy may also affect maternal health. Pregnant women and new mothers are a unique population, with particular mental and physical healthcare needs who are also particularly vulnerable to issues such as domestic violence. Finally, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to be context-specific, and differ depending on a variety of country-specific factors. A global pandemic is likely to only reveal its consequences after significant time passes, and literature published before or immediately after policies are implemented may not capture all relevant outcomes. The goal of this sco** review is to synthesize the current literature on both the direct consequences of contracting COVID-19 during pregnancy and the indirect consequences of the pandemic for pregnant individuals and mothers, taking into account the myriad ways in which containment and prevention measures have disrupted daily life.

Methods

This sco** review followed the framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [4], in order to map the existing literature on the direct and indirect impacts of COVID-19 on maternal health, incorporating the following 5 stages:

Identify research question

How has the COVID-19 pandemic directly and indirectly impacted maternal health globally?

Identify relevant types of evidence

Literature published in English from January 1st, 2020 to September 11, 2020 was included in the search. The search strategy involved the algorithm used by the Maternal Health Task Force’s Buzz, a biweekly e-newsletter presenting current research relevant to maternal health. Hand searches were conducted in PubMed using MeSH terms (see Additional file 1), along with broader searches of “COVID” and “corona” followed by the terms: “pregnant”, “maternal”, “women”, “reproductive”, “economic”, “social”, “indirect”, “direct.” Google Scholar was also searched using these terms to capture grey literature, such as news articles and working papers that have not yet completed the peer review process. This sco** review aimed to capture rapidly evolving evidence in a timely manner, including issues not yet addressed in well-funded, epidemiological studies. The snowball method of consulting sources’ bibliographies was used for certain articles to supplement referenced evidence. The search strategy as outlined above was not registered with PROSPERO.

Study selection

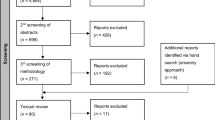

Literature was included if published during the time frame outlined above and primarily assessed the direct or indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal health. Search terms utilized did not directly address neonatal health, but publications on topics relevant to both populations (transmission, breastfeeding, maternity care practices) were also included if returned by the search terms. Case reports, case series, qualitative studies, systematic and sco** reviews, and meta-analyses were included. As some publications included were systematic or sco** reviews or meta-analyses, there was some duplication in data on which publications were based. The article containing the more complete description of the data was used for data charting. Sources were excluded if they consisted only of recommendations for future research. Predictive research was excluded if it consisted only of speculation referencing past epidemics but included if based on quantitative methods. News articles, reports, and other grey literature were included if they contained quantifiable evidence (case reports, survey results, qualitative analyses).After reading full texts and synthesizing relevant evidence, literature was organized thematically. Themes were discussed and decided upon by all four authors. Themes that reflected potential impacts of COVID-19, but for which no quantitative evidence existed were excluded from the review. Of 200 peer-reviewed articles, 129 were excluded; 7 did not pertain to maternal health or COVID-19, 3 were responses to articles, and 199 were commentaries, editorials, or practice guidelines which did not contain relevant evidence. Of 196 articles from the grey literature, 172 articles were excluded; 124 did not pertain to maternal health or COVID-19, and 48 did not contain objective information. See Fig. 1 for a visual representation of inclusion and exclusion.

Chart the data

71 peer-reviewed articles and 24 publications from the grey literature were included from the original search. Two peer-reviewed articles that contradicted earlier findings that were published after September 11, 2020 were added. Publications included represented a wide range of methodologies including case reports, case series, observational studies, letters to the editor, and news articles. The authors developed a rubric of major themes that arose in the literature and recorded standard information including location, sampling method, and size of sample, and key findings of each study (see Table 1). An adaptive thematic analysis [5] was applied using the following steps. The authors identified themes in the literature by a reading and discussing each article included. Articles were then coded independently by two authors. All four authors discussed each code and grouped codes into final themes.

Collate, summarize, and report results

Narrative descriptions of the evidence were written for each theme that the authors determined in the above stages. All authors reviewed descriptions for clarity and relevance and some themes were combined post hoc to improve readability and avoid redundancy.

Main text

Direct effects on pregnancy

During pregnancy, people undergo significant physiologic and immunologic alterations to support and protect the develo** fetus. These changes can increase the risk of infection with respiratory viruses for pregnant individuals and their fetuses. Thus, pregnant individuals and their children may be at heightened risk for infection with SARS-CoV-2 [2].

In general, pregnant individuals with COVID-19 do not seem to display more severe disease symptoms than non-pregnant individuals. Most cases among pregnant people are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic [6]. For symptomatic cases, the most common clinical presentations included fever, cough, and dyspnea [17, 18]. Additionally, the non-medical impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is already apparent in this vulnerable population. While short and medium-term consequences of these impacts are emerging, the long-term consequences are currently unknown and will require careful research to be elucidated.

To date, studies of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have, perhaps understandably, given time constraints and availability of data, lacked rigorous methods. To adequately assess these effects, we require research that carefully controls for pre-COVID-19 levels of the different outcomes of interest (e.g. depressive symptoms, C-Section) and population characteristics (e.g. comorbidity, socio-economic status) to more validly assess time trends. While reducing the frequency of prenatal visits in high income countries (HIC) may not necessarily be associated with worse birth outcomes, reducing the basic antenatal care in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) is likely to impact maternal and neonatal health [110, 111]. Continued surveillance and reporting are critical to ascertain whether maternal mortality and morbidity have increased during the pandemic and which populations were affected most severely.

The Covid-19 pandemic has created a multitude of questions regarding the optimal policies to reduce the spread of SARS-Cov-2 while minimizing the unintended detrimental consequences to family wellbeing and gender equity. Salient among these are: in what circumstances should schools and daycares resume care and in what format? Which models of antenatal and delivery care produce optimal outcomes? Which economic relief policies protect gender equity in the workplace and family wellbeing? Heterogeneous and inconsistent application of policies and models for healthcare and childcare delivery both within and across countries, while potentially not ideal for pandemic response, provide a near-natural experiment that helps to explore these questions.

At the same time, policies impacting pregnant and parenting people have been implemented with little evidence. Several of these policies have the potential to significantly harm pregnant individuals’ health and undermine their rights. Most concerning are those that limit emotional support during labor and delivery, mandate early infant separation, and shorten postpartum stays. While the clinical rationale behind high C-section rates among pregnant individuals diagnosed with Covid-19 are unclear, these rates are alarming given that no evidence exists that C-section delivery lowers risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 or improves maternal health [81, 112].

These concerns lead us to provide several clear policy recommendations we believe either have sufficient evidence to merit implementation or must be pursued because of ethical and human rights considerations. The first two pertain to healthcare policy. Given the evidence on the paucity of severe outcomes from SARS-CoV-2 infection in newborns, we urge the CDC to align with the WHO’s strong recommendation to keep the mother/infant dyad together even if the mother has a confirmed infection of SARS-CoV-2. Precautions, of course, are warranted, but our opinion is that the overwhelming evidence behind the benefits of early bonding and breastfeeding outweigh the risk of infection in the newborn.

Second, whenever possible, healthcare organizations should consider the mental health impacts of any policies implemented to reduce risk of transmission. Early and convincing evidence currently exists that maternal mental health issues have increased during the pandemic. Policies that limit or eliminate the ability to give birth with a support person present or that are likely to increase distress, potentially exacerbating underlying mental health issues, should be avoided. With many healthcare organizations shortening postpartum hospital stays or providing postpartum visits through telemedicine, there is also the risk that screening for postpartum depression or other mental health issues will be forgotten or glossed over. Healthcare providers should be vigilant of the increased mental health needs of their pregnant and parenting patients.

Finally, daycare and school closures are causing incredible stress and destabilization to caregivers, especially women, who often bear the brunt of childcare duties. These closures along with other workplace related consequences of the pandemic pose a serious threat to gender equity in the workforce. Without serious mitigation through policy, this threat is potentially far-reaching. We strongly recommend that governments prioritize the resumption of schooling under safe conditions and childcare when easing shelter in place or other pandemic-related restrictions. Failure to do so is likely to worsen any short-term losses in women’s employment given women’s disproportionate burden of childcare, and to put vulnerable single-mother and low income households at risk of poverty and food insecurity.

Conclusion

While rigorous studies have not yet been conducted, early evidence from this sco** review shows that many of the social and economic consequences of the COVID-19 crisis likely affect women more than men. The low risk of mother to child transmission in-utero or via breast milk is well documented. It seems that pregnancy may constitute a particularly vulnerable period for COVID-19, but this requires further confirmation through well designed and implemented research. An increased risk of distress and psychiatric problems during pregnancy and postnatally during the pandemic is likely, but also in this case high-quality evidence is lacking. Likewise, a rise in the prevalence of domestic violence is plausible and supported by several studies, but we need more representative data. Studies of maternal morbidity and mortality are also lacking. Rigorous epidemiological studies must document the health impact of infection with SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy as well as the changes in health care service and accessibility and their impact on maternal health. This review, however, provides good evidence that mothers with children are more likely to suffer job and income losses during the pandemic than men and women without children. Single mothers in particular are likely to suffer from food insecurity. These socioeconomic consequences for women are similar across many high- and low-income countries.

Availability of data and materials

Full review algorithm will be made available.

Change history

30 March 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-023-01575-2

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus Disease 2019

- DV:

-

Domestic violence

- LMIC:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- HIC:

-

High income countries

- PTSD:

-

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- C-section:

-

Cesarean section

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

References

WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard | WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. (n.d.). Retrieved December 29, 2020, https://covid19.who.int/table

Muralidar S, Ambi SV, Sekaran S, Krishnan UM. The emergence of COVID-19 as a global pandemic: Understanding the epidemiology, immune response and potential therapeutic targets of SARS-CoV-2. Biochimie. 2020;179:85–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2020.09.018.

Pradhan A, Olsson P-E. Sex differences in severity and mortality from COVID-19: are males more vulnerable? Biol Sex Differ. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-020-00330-7.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Sco** studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Braun V, Clarke V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2014. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.26152.

Delahoy MJ. Characteristics and Maternal and Birth Outcomes of Hospitalized Pregnant Women with Laboratory-Confirmed COVID-19—COVID-NET, 13 States, March 1–August 22, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: MMWR; 2020. p. 69.

Wu C, Yang W, Wu X, Zhang T, Zhao Y, Ren W, **a J. Clinical manifestation and laboratory characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women. Virologica Sinica. 2020;35(3):305–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12250-020-00227-0.

Xu L, Yang Q, Shi H, Lei S, Liu X, Zhu Y, Wu Q, Ding X, Tian Y, Hu Q, Chen F, et al. Clinical presentations and outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infected pneumonia in pregnant women and health status of their neonates. Sci Bull. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2020.04.040.

Smith V, Seo D, Warty R, Payne O, Salih M, Chin KL, Ofori-Asenso R, et al. Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes Associated with COVID-19 Infection: a Systematic Review. PLoS ONE. 2020;5(6):e0234187. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234187.

Knight M, Bunch K, Vousden N, Morris E, Simpson N, Gale C, O’Brien P, Quigley M, Brocklehurst P, Kurinczuk JJ. Characteristics and Outcomes of Pregnant Women Admitted to Hospital with Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infection in UK: National Population Based Cohort Study. BMJ. 2020;369:2107. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2107.

Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, Yap M, Chatterjee S, Kew T, Debenham L, Llavall AC, Dixit A, Zhou D, Balaji R, Lee SI, Qiu X, Yuan M, Coomar D, van Wely M, van Leeuwen E, Kostova E, Kunst H. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3320.

Pereira A, Cruz-Melguizo S, Adrien M, Fuentes L, Marin E, Perez-Medina T. Clinical Course of Coronavirus Disease-2019 in Pregnancy. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2020;99(7):839–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13921.

Blitz MJ, Rochelson B, Meirowitz N, Prasannan L, Rafael TJ, et al. Maternal mortality among women with coronavirus disease 2019. Am J Obstetr Gynecol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.06.020.

Chen H, Guo J, Wang C, Luo F, Yu X, Zhang W, Li J, Zhao D, Xu D, Gong Q, Liao J, et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020;395(10226):809–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3.

Yang H, Sun G, Tang F, Peng M, Gao Y, Peng J, **e H, Zhao Y, ** Z. Clinical features and outcomes of pregnant women suspected of coronavirus disease 2019. J Infect. 2020;81(1):e40-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.**f.2020.04.003.

Khan S, Peng L, Siddique R, Nabi G, Xue M, Liu J, Han G. Impact of COVID-19 infection on pregnancy outcomes and the risk of maternal-to-neonatal intrapartum transmission of COVID-19 during natural birth. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41(6):748–50. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2020.84.

DeBolt CA, Bianco A, Limaye MA, Silverstein J, Penfield CA, Roman AS, Rosenberg HM, Ferrara L, Lambert C, Khoury R, Bernstein PS. Pregnant women with severe or critical coronavirus disease 2019 have increased composite morbidity compared with nonpregnant matched controls. Am J Obst Gynecol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.11.022.

Zambrano LD, Ellington S, Strid P, Galang RR, Oduyebo T, Tong VT, Woodworth KR, Nahabedian III JF, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Gilboa SM, Meaney-Delman D. Update: characteristics of symptomatic women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status—United States, January 22–October 3, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6944e3

Lokken EM, Walker CL, Delaney S, Kachikis A, Kretzer NM, Erickson A, Resnick R, Vanderhoeven J, Hwang JK, Barnhart N, Rah J. Clinical characteristics of 46 pregnant women with a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in Washington State. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020.

Savasi VM, Parisi F, Patanè L, Ferrazzi E, Frigerio L, Pellegrino A, Spinillo A, Tateo S, Ottoboni M, Veronese P, Petraglia F. Clinical findings and disease severity in hospitalized pregnant women with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Obstetr Gynecol. 2020;136(2):252–8.

Khalil A, von Dadelszen P, Draycott T, Ugwumadu A, O’Brien P, Magee L. Change in the Incidence of Stillbirth and Preterm Delivery During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(7):705–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.12746.

Mendoza M, Garcia-Ruiz I, Maiz N, Rodo C, Garcia-Manau P, Serrano B, Lopez-Martinez RM, Balcells J, Fernandez-Hidalgo N, Carreras E, Suy A. Preeclampsia-like syndrome induced by severe COVID-19: a prospective observational study. BJOG. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16339.

Ferraiolo A, Barra F, Kratochwila C, Paudice M, Vellone VG, Godano E, Varesano S, Noberasco G, Ferrero S, Arioni C. Report of positive placental swabs for SARS-CoV-2 in an asymptomatic pregnant woman with COVID-19. Medicina. 2020;56(6):306.

Hosier H, Farhadian S, Morotti R, Deshmukh U, Lu-Culligan A, Campbell K, Yasumoto Y, Vogels C, Casanovas-Massana A, Vijayakumar P, Geng B. SARS-CoV-2 infection of the placenta. medRxiv. 2020..

Golden TN, Simmons RA. Maternal and Neonatal Response to COVID-19. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2020;319(2):E315-9. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00287.2020.

Huntley BJ, Huntley ES, Di Mascio D, Chen T, Berghella V, Chauhan SP. Rates of maternal and perinatal mortality and vertical transmission in pregnancies complicated by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-Co-V-2) infection: a systematic review. Obstetr Gynecol. 2020;136(2):303–12.

Kotlar B, Gerson E, Petrillo S, Langer A, Tiemeier H. Maternal Transmission of SARS-COV-2 to the Neonate, and Possible Routes for Such Transmission: A Systematic Review and Critical Analysis. BJOG. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16362.

Zhang L, Dong L, Ming L, Wei M, Li J, Hu R, Yang J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2(SARS-CoV-2) infection during late pregnancy: a report of 18 patients from Wuhan China. BMC Pregn Childbirth. 2020;20(1):394. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03026-3.

Martins-Filho PR, Santos VS, Santos HP. To breastfeed or not to breastfeed? Lack of evidence on the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in breastmilk of pregnant women with COVID-19. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. 2020;44: e59. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2020.59.

Perrone S, Giordano M, Meoli A, Deolmi M, Marinelli F, Messina G, Lugani P, Moretti S, Esposito S. Lack of viral transmission to preterm newborn from a COVID-19 positive breastfeeding mother at 11 days postpartum. J Med Virol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26037.

Zeng H, Xu C, Fan J, Tang Y, Deng Q, Zhang W, Long X. Antibodies in Infants Born to Mothers With COVID-19 Pneumonia. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1848–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4861.

Dong L, Tian J, He S, Zhu C, Wang J, Liu C, Yang J. Possible vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from an infected mother to her newborn. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1846–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4621.

Kimberlin DW, Stagno S. Can SARS-CoV-2 infection be acquired in utero?: more definitive evidence is needed. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1788–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4868.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z. Clinical Features of Patients Infected with 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506.

Wang W, Yanli X, Gao R, Roujian L, Han K, Guizhen W, Tan W. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1843–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3786.

Egloff C, Vauloup-Fellous C, Picone O, Mandelbrot L, Roques P. Evidence and possible mechanisms of rare maternal-fetal transmission of SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Virol. 2020;128:104447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104447.

Wu Y, Liu C, Dong L, Zhang C, Chen Y, Liu J, Zhang C, et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 among pregnant chinese women: case series data on the safety of vaginal birth and breastfeeding. BJOG. 2020;127(9):1109–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16276.

Ashokka B, Loh MH, Tan CH, Su LL, Young BE, Lye DC, Biswas A, Illanes SE, Choolani M. Care of the pregnant woman with coronavirus disease 2019 in labor and delivery: anesthesia, emergency cesarean delivery, differential diagnosis in the acutely ill parturient, care of the newborn, and protection of the healthcare personnel. Am J Obstetr Gynecol. 2020;223:66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.005.

Oxford-Horrey C, Savage M, Prabhu M, Abramovitz S, Griffin K, LaFond E, Riley L, Easter SR. Putting it all together: clinical considerations in the care of critically ill obstetric patients with COVID-19. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37(10):1044–51. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1713121.

Della Gatta AN, Rizzo R, Pilu G, Simonazzi G. COVID19 during pregnancy: a systematic review of reported cases. Am J Obst Gynecol. 2020.

Zaigham M, Andersson O. Maternal and perinatal outcomes with COVID-19: a systematic review of 108 pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(7):823–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13867.

Chen L, Li Q, Zheng D, Jiang H, Wei Y, Zou L, Feng L, **ong G, Sun G, Wang H, Zhao Y. Clinical characteristics of pregnant women with Covid-19 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020.

Malhotra Y, Miller R, Bajaj K, Sloma A, Wieland D. No Change in Cesarean Section Rate during COVID-19 Pandemic in New York City. Eur J Obst Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.06.010.

COVIDSurg Collaborative. Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: Global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. Br J Surg. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11746.

Narang K, Ibirogba ER, Elrefaei A, Trad AT, Theiler R, Nomura R, Picone O, Kilby M, Escuriet R, Suy A, Carreras E. SARS-CoV-2 in pregnancy: a comprehensive summary of current guidelines. J Clin Med. 2020;9(5):1521. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9051521.

Continuous support for women during childbirth—Bohren, MA - 2017 | Cochrane Library. (n.d.). Retrieved December 29, 2020, from https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub6/full?cookiesEnabled.

Lei D, Wang C, Li C, Fang C, Yang W, Chen B, Wei M, Xu X, Yang H, Wang S, Fan C. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in pregnancy: analysis of nine cases. Chin J Perinatal Med. 2020 Mar 16;23(3):225–31.

Wang S, Guo L, Chen L, Liu W, Cao Y, Zhang J, Feng L. A case report of neonatal 2019 coronavirus disease in China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):853–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa225.

Zhu C, Liu W, Su H, Li S, Shereen MA, Lv Z, Niu Z, Li D, Liu F, Luo Z, **a Y. nBreastfeeding risk from detectable severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in Breastmilk. J Infect. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.**f.2020.06.001.

Dong Y, Chi X, Hai H, Sun L, Zhang M, **e WF, Chen W. Antibodies in the breast milk of a maternal woman with COVID-19. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):1467–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1780952.

Bastug A, Hanifehnezhad A, Tayman C, Ozkul A, Ozbay O, Kazancioglu S, Bodur H. Virolactia in an asymptomatic Mother with COVID-19. Breastfeeding Med. 2020;15(8):488–91. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2020.0161.

Wu Y, Zhang C, Liu H, Duan C, Li C, Fan J, Li H, Chen L, Xu H, Li X, Guo Y. Perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms of pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. Am J Obstetr Gynecol. 2020;223(2):240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.009.

Saccone G, Florio A, Aiello F, Venturella R, De Angelis MC, Locci M, Bifulco G, Zullo F, Sardo AD. Psychological impact of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnant women. Am J Obstetr Gynecol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.003.

Jungari S. Maternal Mental Health in India during COVID-19. Public Health. 2020;185:97–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.062.

Aryal S, Pant SB. Maternal mental health in Nepal and its prioritization during COVID-19 pandemic: missing the obvious. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;54:102281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102281.

Kotabagi P, Fortune L, Essien S, Nauta M, Yoong W. Anxiety and depression levels among pregnant women with COVID-19. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2020;99(7):953–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13928.

Chivers BR, Garad RM, Boyle JA, Skouteris H, Teede HJ, Harrison CL. Perinatal distress During COVID-19: thematic analysis of an online parenting forum. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9):e22002. https://doi.org/10.2196/22002.

Koenen KC. Pregnant During a Pandemic? Psychology Today. 2020. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/mental-health-around-the-world/202007/pregnant-during-pandemic?eml

Thapa SB, Mainali A, Schwank SE, Acharya G. Maternal Mental Health in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2020;99(7):817–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13894.

Thomas C, Morris SM, Clark D. Place of death: preferences among cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(12):2431–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113348.

Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. 2020. https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/langlo/PIIS2214-109X(20)30229-1.pdf

Menendez C, Gonzalez R, Donnay F, Leke RG. Avoiding indirect effects of COVID-19 on maternal and child health. Lancet Global Health. 2020.

Ramoni R. How COVID-19 Is Affecting Antenatal Care. Daily Trust. 2020, sec. News. https://dailytrust.com/how-covid-19-is-affecting-antenatal-care.

Aryal S, Shrestha D. Motherhood in Nepal during COVID-19 pandemic: are we heading from safe to unsafe?. J Lumbini Med College. 2020. https://doi.org/10.22502/jlmc.v8i1.351.

Pallangyo E, Nakate MG, Maina R, Fleming V. The impact of Covid-19 on midwives’ practice in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania: a reflective account. Midwifery. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2020.102775.

Population Council. Kenya: COVID-19 Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices and Needs—Responses from Second Round of Data Collection in Five Nairobi Informal Settlements (Kibera, Huruma, Kariobangi, Dandora, Mathare). Poverty, Gender, and Youth, 2020. https://doi.org/10.31899/pgy14.1013.

ReliefWeb. Rapid Gender Analysis - COVID-19 : West Africa – April 2020 - Benin. 2020. https://reliefweb.int/report/benin/rapid-gender-analysis-covid-19-west-africa-april-2020.

Semaan AT, Audet C, Huysmans E, Afolabi BB, Assarag B, Banke-Thomas A, Blencowe H, Caluwaerts S, Campbell OM, Cavallaro FL, Chavane L. Voices from the frontline: findings from a thematic analysis of a rapid online global survey of maternal and newborn health professionals facing the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Global Health. 2020;5(6):e002967. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002967.

Coxon K, Turienzo CF, Kweekel L, Goodarzi B, Brigante L, Simon A, Lanau MM. The Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on maternity care in Europe. Midwifery. 2020;88:102779–102779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2020.102779.

Ayenew B, Pandey D, Yitayew M, Etana D, Binay Kumar P, Verma N. Risk for Surge Maternal Mortality and Morbidity during the Ongoing Corona Virus Pandemic. Med Life Clin. 2020;2(1):1012.

Stevis-Gridneff M, Alisha HG, Monica P. Oronavirus Created an Obstacle Course for Safe Abortions. New York TImes. 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/14/world/europe/coronavirus-abortion-obstacles.html.

Sobel L, Ramaswamy A, Frederiksen B, Salganicoff A. State Action to Limit Abortion Access During the COVID-19 Pandemic. KFF(blog), 2020. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/state-action-to-limit-abortion-access-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

UNFPA. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Family Planning and Ending Gender-Based Violence, Female Genital Mutilation and Child Marriage. UNFPA, 2020.

Federation, International Planned Parenthood. COVID-19 Pandemic Cuts Access to Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare for Women around the World. News Release. Published Online April 9, 2020, n.d.

Jeffrey G, Raj S. 8 Hospitals in 15 Hours: A Pregnant Woman’s Crisis in the Pandemic.” New York Times. 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/21/world/asia/coronavirus-india-hospitals-pregnant.html.

Kumari V, Mehta K, Choudhary R. COVID-19 outbreak and decreased hospitalisation of pregnant women in labour. Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(9):e1116–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30319-3.

Takemoto ML, Menezes MO, Andreucci CB, Knobel R, Sousa L, Katz L, Fonseca EB, Nakamura-Pereira M, Magalhães CG, Diniz CS, Melo AS. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for mortality in obstetric patients with severe COVID-19 in Brazil: a surveillance database analysis. BJOG. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1786056.

Rafaeli T, Hutchinson G. The Secondary Impacts of COVID-19 on Women and Girls in Sub-Saharan Africa, (n.d.). Resource Centre. Retrieved December 29, 2020, from https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/node/18153/pdf/830_covid19_girls_and_women_ssa.pdf

Khalil A, Von-Dadelszen P, Draycott T, Ugwumadu A, O’Brien P, Magee L. Change in the incidence of stillbirth and preterm delivery during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(7):705–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.12746.

KC, A., Gurung, R., Kinney, M. V., Sunny, A. K., Moinuddin, M., Basnet, O., Paudel, P., Bhattarai, P., Subedi, K., Shrestha, M. P., Lawn, J. E., & Målqvist, M. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic response on intrapartum care, stillbirth, and neonatal mortality outcomes in Nepal: A prospective observational study. Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(10):e1273–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30345-4.

Been JV, Ochoa LB, Bertens LC, Schoenmakers S, Steegers EA, Reiss IK. Impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on the incidence of preterm birth: A national quasi-experimental study. MedRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.01.20160077.

Shuchman M. Low-and middle-income countries face up to COVID-19. Nature Medicine. 2020;26(7):986–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41591-020-00020-2.

Bong CL, Brasher C, Chikumba E, McDougall R, Mellin-Olsen J, Enright A. The COVID-19 pandemic: effects on low-and middle-income countries. Anesthesia Analgesia. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000004846.

Hupkau C, Petrongolo B. COVID-19 and Gender Gaps: Latest Evidence and Lessons from the UK. VoxEU. Org22. 2020.

Boniol M, McIsaac M, Xu L, Wuliji T, Diallo K, Campbell J. Gender equity in the health workforce: Analysis of 104 countries, viewed 27 April 2020. 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311314/WHO-HIS-HWF-Gender-WP1-2019.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Robertson C, Gebeloff R. How Millions of Women Became the Most Essential Workers in America. The New York Times, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/18/us/coronavirus-women-essential-workers.html.

Jankowski J, Davies A, English P, Friedman E, McKeown H, Rao M, Sethi S, Strain WD. Risk Stratification for Healthcare Workers during CoViD-19 Pandemic: Using Demographics, Co-Morbid Disease and Clinical Domain in Order to Assign Clinical Duties. Medrxiv. 2020.

World Health Organization. Shortage of Personal Protective Equipment Endangering Health Workers Worldwide. World Health Organization. 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/03-03-2020-shortage-of-personal-protective-equipment-endangering-health-workers-worldwide.

Alon TM, Doepke M, Olmstead-Rumsey J, Tertilt M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020.

Johnston RM, Mohammed A, van der Linden C. Evidence of exacerbated gender inequality in child care obligations in Canada and Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Politics Gender. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X20000574.

Malik S, Naeem K. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Women: Health, livelihoods & domestic violence. Sustainable Development Policy Institute. 2020. http://www.jstor.com/stable/resrep24350

UN Women. The Private Sector's Role in Mitigating the Impact of COVID-19 on Vulnerable Women and Girls in Nigeria. 2020. https://www.weps.org/resource/private-sectors-role-mitigating-impact-covid-19-vulnerable-women-and-girls-nigeria

Wahome C. Impact of Covid-19 on Women Workers in the Horticulture Sector in Kenya. Hivos. 2020. https://www.hivos.org/assets/2020/05/Hivos-Rapid-Assessment-2020.pdf

World Vision International Cambodia. Rapid Assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on child wellbeing in Cambodia Summary Report. 2020. https://www.wvi.org/publications/cambodia/rapid-assessment-summary-report-impact-covid-19-childrens-well-being-cambodia

Staff of the National Estimates Branch. Current Employment Statistics Highlights. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/ceshighlights.pdf.

Adams-Prassl A, Boneva T, Golin M, Rauh C. Inequality in the Impact of the Coronavirus Shock: Evidence from Real Time Surveys. IZA Discussion Papers. 2020. https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/13183/inequality-in-the-impact-of-the-coronavirus-shock-evidence-from-real-time-surveys

Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19): Violence, Reproductive Rights and Related Health Risks for Women, Opportunities for Practice Innovation. 2020 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7275128/

Wanqing Z. Domestic Violence Cases Surge During COVID-19 Epidemic. Sixth Tone, 2020. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1005253/domestic-violence-cases-surge-during-covid-19-epidemic.

Euronews. Domestic Violence Cases Jump 30% during Lockdown in France. euronews, 2020. https://www.euronews.com/2020/03/28/domestic-violence-cases-jump-30-during-lockdown-in-france.

Women, U. N. COVID-19 and Ending Violence against Women and Girls. New York. 2020.

Sigal L, Ramos Miranda NA, Martinez AI, Machicao M.Another Pandemic: In Latin America, Domestic Abuse Rises amid Lockdown. Reuters, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-latam-domesticviol/another-pandemic-in-latin-america-domestic-abuse-rises-amid-lockdown-idUSKCN2291JS.

Graham-Harrison E, Giuffrida A, Smith H, Ford L. Lockdowns around the World Bring Rise in Domestic Violence. The Guardian. 2020, sec. Society. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/mar/28/lockdowns-world-rise-domestic-violence.

Bosman J. Domestic Violence Calls Mount as Restrictions Linger: ‘No One Can Leave. New York Times. 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/15/us/domestic-violence-coronavirus.html.

Women’s Safety NSW. “New Domestic Violence Survey in NSW Shows Impact of COVID-19 on the Rise.” Women’s Safety NSW, April 3, 2020. https://www.womenssafetynsw.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/03.04.20_New-Domestic-Violence-Survey-in-NSW-Shows-Impact-of-COVID-19-on-the-Rise.pdf.

Biaggi A, Conroy S, Pawlby S, Pariante CM. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:62–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.014.

Kaur R, Garg S. Addressing domestic violence against women: an unfinished agenda. Indian J Commun Med. 2008;33(2):73–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.40871.

Dennis CL, Vigod S. The relationship between postpartum depression, domestic violence, childhood violence, and substance use: epidemiologic study of a large community sample. Violence Against Women. 2013 Apr;19(4):503–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801213487057.

Kem J. Framework in Ending Violence Against women and Girls with the Advent of the COVID 19 from an African Perspective. 2020. Available at SSRN 3575288.

Mukherjee S, Dasgupta P, Chakraborty M, Biswas G, Mukherjee S. Vulnerability of Major Indian States Due to COVID-19 Spread and Lockdown. 2020.

Carter Ebony B, Tuuli Methodius G, Caughey Aaron B, Odibo Anthony O, Macones George A, Cahill Alison G. Number of prenatal visits and pregnancy outcomes in low-risk women. J Perinatol. 2016;36(3):178–81. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2015.183.

Gajate-Garrido G. The impact of adequate prenatal care on urban birth outcomes: an analysis in a develo** country context. Econ Dev Cult Change. 2013;62(1):95–130. https://doi.org/10.1086/671716.

Panagiotakopoulos L. SARS-CoV-2 infection among hospitalized pregnant women: Reasons for admission and pregnancy characteristics—Eight US health care centers, March 1–May 30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: MMWR; 2020. p. 69.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This project was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number and title for grant amount (T76 MC000010, Maternal and Child Health Training Grant). This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BK designed the study, reviewed literature, and drafted the manuscript. EMG and SP retrieved and summarized the literature, reviewed the literature and drafted the manuscript. AL advised on the review and reviewed the final manuscript. HT designed the study, supervised the review process and reviewed the draft and final manuscripts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable in review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable in review.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: author Emily Gerson asked to change her name from Emily Gerson to Emily Michelle Gerson.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Pubmed MeSH Terms Utilized for Peer-Reviewed Articles.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kotlar, B., Gerson, E.M., Petrillo, S. et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal health: a sco** review. Reprod Health 18, 10 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01070-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01070-6