Abstract

Background

Polypharmacy is common in chronic medication users, which increases the risk of drug related problems. A suitable intervention is the clinical medication review (CMR) that was introduced in the Netherlands in 2012, but the effectiveness might be hindered by limited implementation in community pharmacies. Therefore our aim was to describe the current implementation of CMRs in Dutch community pharmacies and to identify barriers to the implementation.

Methods

An online questionnaire was developed based on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and consisted of 58 questions with open ended, multiple choice or Likert-scale answering options. It was sent out to all Dutch community pharmacies (n = 1,953) in January 2021. Descriptive statistics were used.

Results

A total of 289 (14.8%) community pharmacies filled out the questionnaire. Most of the pharmacists agreed that a CMR has a positive effect on the quality of pharmacotherapy (91.3%) and on medication adherence (64.3%). Pharmacists structured CMRs according to available selection criteria or guidelines (92%). Pharmacists (90%) believed that jointly conducting a CMR with a general practitioner (GP) improved their mutual relationship, whereas 21% believed it improved the relationship with a medical specialist. Lack of time was reported by 43% of pharmacists and 80% (fully) agreed conducting CMRs with a medical specialist was complicated. Most pharmacists indicated that pharmacy technicians can assist in performing CMRs, but they rarely do in practice.

Conclusions

Lack of time and suboptimal collaboration with medical specialists are the most important barriers to the implementation of CMRs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

As much as 48% of all people are using chronic medication in the European Union [1]. Taking five or more medications simultaneously is known as ‘polypharmacy’ and increases with age [2]. For the age group of 65–74, 25.3% are patients with polypharmacy, and this number increases to 46.5% for patients aged 85 years or older [3]. Polypharmacy can lead to the suboptimal use of medication and increases the likelihood of drug-related problems [4, 5]. For example, taking more drugs simultaneously increases the likelihood that one of these drugs leads to drug-related problems such as side-effects. The risk of drug-related problems increases linearly with the number of prescribed medication and higher age [6]. Even though almost half of drug-related problems are potentially preventable, they still account for more than 15% of hospital admissions [7].

A suitable intervention to target potential problems related to polypharmacy and drug related problems is a clinical medication review (CMR). A CMR is a structured, critical examination of a patient’s medicines. Its objective is to reach an agreement with the patient about treatment, optimizing the impact of medicines, minimizing the number of DRPs and reducing drug waste. The details of a CMR have been described in the publication by Mast et al. (2015) [8]. . The CMR aims to prevent worse outcomes or complications due to the disease or the pharmacotherapeutic intervention itself. The CMR was introduced in the Dutch primary care setting with the Multidisciplinary Guideline Polypharmacy and consists of the steps pharmacotherapeutic anamnesis [1], pharmacotherapeutic analysis [2], determining treatment plan with GP or specialist [3], determining treatment plan with the patient [4] and follow-up [5, 9].

Several studies have shown positive effects of CMRs, for example on lowering the amount of drug related problems or blood pressure [10,11,12,13]. However, other studies show limited or no effects of CMRs on clinical outcomes [14, 15]. For example, Huiskes et al. (2017) showed in their systematic review that CMRs resulted in a decrease in the number of drug-related problems, but minimal effects on clinical outcomes and no effects on quality of life [14].

This lack of consistent findings on clinical outcomes for CMRs might be explained by the degree in which CMRs are implemented, as several studies have shown major barriers for the performance of CMRs by pharmacists. In a Swiss evaluation on the implementation of CMRs, the authors concluded that successful implementation was hindered by a lack of a strong local network of community pharmacists with physicians, an effective workflow management and a practice- and communications-focused training for pharmacists and their teams [16]. In a German study, authors concluded that Pharmacist-led CMRs were hindered by a lack of patients’ confidence in pharmacists’ expertise and facilitated by pharmacies’ digital records of the patients’ medications [17].

In the Netherlands, the setting of our study, the Multidisciplinary Guideline Polypharmacy integrated the CMR into usual care in 2012 [9]. Two years after the development of this guideline in the Netherlands, CMRs were considered sub-optimally implemented according to Bakker et al. (2017) [18]. Their survey showed that the guideline was used only by 26% of the healthcare providers (HCPs) involved and that only 43% of the patients with polypharmacy had their medication assessed in the year previous to the survey. Factors contributing to the lack of implementation were the large number of patients eligible for a CMR, inadequate selection criteria, the time consuming and inefficient review procedure, a lack of collaboration between HCPs and insufficient reimbursement [18]. In order to improve the implementation rate, in 2015 the Dutch Health Inspectorate (DHI) tightened the selection criteria and required community pharmacists (CPs) and general practitioners (GPs) to annually perform a minimum number of CMRs in high-risk patients only [19].

The current study expands on the study by Bakker et al. (2017) [18] and aims to give an update on the nationwide implementation of CMRs, ten years after the inception of the Dutch Multidisciplinary Guideline Polypharmacy. The aim of this study was to describe the current implementation of CMRs in Dutch community pharmacies and to identify barriers that might hinder the implementation.

Methods

Study design and setting

An online questionnaire on the implementation of CMRs was sent out by e-mail to all community pharmacies (N = 1953) in the Netherlands by making use of the membership list of the Royal Dutch Association of Pharmacists (Dutch: Koninklijke Nederlandse Maatschappij ter bevordering der Pharmacie (KNMP)).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In the Netherlands, completing a survey does not fall under the scope of the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act [32]. This law states that medical ethical review is only required when research involves human subjects and if people are being subjected to actions or if rules of behaviour are imposed on them. As our research consisted of a questionnaire that did not impose any rule or behaviour on our subjects, a medical ethics review of the study protocol was not required. Therefore, all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire was developed by two researchers (SH and JH) based on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). The CFIR is an implementation framework aimed to evaluate an implementation study or to design an implementation study [20]. The CFIR provides a pragmatic structure for approaching complex, interacting, multi-level, and transient states of constructs in the real world by embracing, consolidating, and unifying key constructs from published implementation theories. The CFIR consists of the domains intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals and process. Each domain is divided into several constructs. This study used the CFIR framework as a guide to ensure all relevant concepts for implementation were present in the developed questionnaire to promote the generalizability of this research. Some CFIR constructs were omitted because they were deemed not relevant for this study based on consensus discussions between SH and JH. For an overview of included and omitted CFIR constructs, see Table 1. Appendix A gives a full overview of the developed questionnaire and all of its questions according to CFIR domains and constructs. The final questionnaire consisted of 58 questions with either multiple choice, Likert-scale or open ended answering options.

Before sending the questionnaire to all community pharmacies in the Netherlands, the questionnaire was pilot tested for face validity by four community pharmacists, working in different types of pharmacies (independent, formula (i.e. franchise) and chain). The communication department of the Royal Dutch Association of Pharmacists reviewed the questionnaire before distribution. Both the pilot testing and review by the communication department did not lead to any major changes in the questionnaire, apart from changing the order in which questions were asked.

Data collection

Data were collected by using the survey software Questback (SaaS, Questback, Oslo, Norway). Responses were collected from January 5th 2021 till January 18th 2021. A reminder was sent out on January 15th. 289 pharmacists responded to the questionnaire (response rate = 14.8%). Fourteen pharmacists were excluded from the analyses, because they worked in outpatient hospital pharmacies, pharmacies serving nursing homes and central filling pharmacies, and their patient population is generally different from the patient population of community pharmacies and they rarely conduct a CMR. Pharmacists received an invitation letter by mail before the start of the questionnaire. Informed consent was asked prior to the questionnaire.

Analyses

All data were analyzed using SPSS 27.0 (IBM Corp., Chicago, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to provide percentages (categorical variables) or means and standard deviations (continuous variables). Open ended questions are presented as quotes.

Results

Characteristics of included pharmacies

Table 2 gives an overview of characteristics of the included pharmacies. A total of 275 pharmacists were included in analyses. Community pharmacies had 9,438 patients on average. Almost half (49.3%) of community pharmacies were located in a healthcare center and the majority (70.6%) were part of a pharmacy chain or formula.

Intervention characteristics

Results are presented according to the five CFIR domains. Most of the pharmacists agreed that a CMR has a positive effect on the quality of pharmacotherapy (91.3%) and on medication adherence (64.3%). The majority of pharmacists (79.6%) considered conducting a CMR with patients of which a medical specialists was the prescribers as complex. Most pharmacists (95.6%) indicated that health insurers should use a uniform reimbursement for CMRs. Most common parameters used for selecting patients for a CMR included the number of medications in chronic use (92.0%), age (89.1%) and the specific GP by which a patient is treated (58.5%), followed by poor medication adherence (55.6%), cognition (49.8%), fall risk (49.1%) and residential location such as living in a nursing home (47.6%).

Outer setting

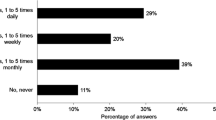

Table 3 gives an overview of the opinion of pharmacists on statements related to the CFIR domain ‘outer setting’. Almost all pharmacists thought that a CMR promotes the relationship with patients (93.5%) and the GP (90.2%). Most pharmacists (73.9%) thought that the content of a CMR meets the patient’s care needs. Almost half of the pharmacist stated that they never or rarely met with homecare (42.2%) or a medical specialist (44.7%) to discuss a CMR. Patients were most often invited for a CMR by phone (66.1%), followed by letter (23.5%), by other means not specified (7.3%), at the front desk (2.4%) or by e-mail (0.7%).

Inner setting

Table 4 shows the answers of pharmacists regarding the CFIR domain ‘inner setting’. Pharmacists conducted 56 CMRs annually on average. Pharmacies participated on average annually in 2.8 pharmacotherapeutic audit meetings (PTAM, i.e. regular meeting between CPs and GPs about pharmacotherapy). 41.1% of pharmacists set their own additional goals for conducting CMRs. Most of these own goals relate to specific target populations, such as elderly patients or other vulnerable patient populations. The majority (90.0%) of pharmacists made use of a structured treatment plan when conducting a CMR.

Table 5 shows the responses of community pharmacists on statements regarding the implementation of CMRs in community pharmacies related to the CFIR domain ‘outer setting’. Almost half (42.5%) of pharmacists indicated that they lack time to conduct a CMR and the majority of pharmacists (67.3%) considered the reimbursement for conducting a CMR insufficient. The START-/STOP criteria are used by almost all pharmacists (92.4%) as an aid in conducting CMRs. Other popular tools and criteria are the guideline database of the Dutch Association of Medical Specialists (85.1%), the STRIP method (69.8%), the NHG-standard (56.4%), the Beers criteria (39.6%) and Ephor (39.6%) [21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

Process

Most pharmacists think a pharmacy technician (51.7%) or a higher vocationally educated pharmacy technician (67.3%) can assist the pharmacist in conducting a CMR. About half of the pharmacists considered the selection criteria for CMRs specific enough (52.0%) and (strongly) disagreed (55.7%) that there is a lack of a systematic approach to conduct a CMR. Almost half (48.1%) of pharmacists were stimulated to conduct more CMRs by external organizations, with an average surplus of 13.7 extra CMRs conducted as a result of external stimulation in 2020 per pharmacy. The most common external organization to stimulate a pharmacy to conduct more CMRs were pharmacy chains or formulas and were mostly related to the amount of CMRs conducted (49.0%). For the pharmacotherapeutic anamnesis, the most common method was that patients fills in the questionnaire together with a pharmacy staff member by phone (43.9%), followed by filled in together in the pharmacy (36.7%), filled in by the patient him/herself (17.2%) or together during a video call (2.2%).

Table 6 shows who is responsible for the different stages in the implementation of a CMR according to community pharmacists. In most of the cases, pharmacists and GPs share the responsibility of selecting patients. They also share the responsibility of setting up and evaluating the pharmacotherapeutic treatment plan. In approximately 10% of the pharmacies, pharmacy technicians are responsible for inviting patients and conducting the pharmacotherapeutical anamnesis. Also, in a quarter of pharmacies the GP is responsible for determining the treatment plan with the patient. If a pharmacist filled in ‘other’, GPs assistants were the most common answer. Lastly, in 6.5% of the pharmacies the follow-up and monitoring does not happen.

Discussion

Main findings

In this study the implementation of CMRs in community pharmacies was investigated with a structured online questionnaire based on the CIFR and identified barriers to the implementation of CMRs. Most of the pharmacists agreed that a CMR has a positive effect on the quality of pharmacotherapy and medication adherence. The results further show that pharmacists believe conducting CMRs improves their relationship with GPs and meets patient’s care needs. Collaboration with GPs is generally well established, but collaboration with medical specialists in CMRs is considered complex by the majority of pharmacists. Additionally, both home care and medical specialists are consulted in about half of all cases. The process of conducting CMR takes pharmacists an hour on average, and the majority of pharmacists indicated a lack of time as a major implementation barrier. Pharmacists have indicated that some aspects of conducting a CMR can be delegated to (higher vocationally educated) pharmacy technicians, but the majority of tasks is currently being done by Pharmacists and/or GPs.

Comparison with existing knowledge

Implementing the CMR following the adoption of the guideline ‘Polypharmacy in the elderly’ in 2012, initially proved to be difficult [9, 18, 19]. It appeared that in 2014 only 26% of the community pharmacists performed CMRs [18]. The survey showed that the problems were related to the inadequate selection criteria by which a very large number of patients would be eligible for a CMR, the extraordinary amount of time it would take to perform a CMR in these patients (approximately two hours per patient), and the lack of appropriate remuneration for this specific care activity, which most HCPs did not consider being a part of usual care. In a recent international systematic review on the implementation of CMRs in community pharmacies, collaboration with doctors and insufficient remuneration were also the most dominant barriers [28]. Accordingly, it was concluded that the problems could best be addressed through stricter patient selection, the use of more efficient working methods and the availability of appropriate remuneration [18].

Ten years later, our study showed that the implementation has improved. By now a systematic approach is available and is considered sufficient by most pharmacists, which has decreased the time spend on a CMR by community pharmacists per patient to about an hour. Most pharmacists also do consider the selection criteria appropriate and different tools and guidelines are used more frequently. The majority of pharmacists now involve and consult with GPs on different sub-tasks of CMRs and consider collaborating with GPs as an improvement to the professional relationship they have with GPs. All of this indicates that most major barriers of the past have been overcome, but some other barriers persist. Collaboration with medical specialists is still considered to be complex by most pharmacists, and medical specialists and homecare organizations are not consulted about CMRs with their patients in all cases. Many patients with polypharmacy switch between primary and secondary care, and medication problems derived from collaboration between care domains is a persistent problem [29, 30]. Future studies should therefore explore different ways to improve the relationship with medical specialists and home care organizations. Future studies should therefore explore different types of medical specialists’ views on medication management and their preferred roles in CMRs.

Moreover, lack of time was a barrier identified both in the study by Bakker, Kemper, Wagner et al. [18] and in our results. Over the years, several attempts have been made to increase CMR efficiency and limit the time required to perform a CMR. Our results suggest that (higher vocationally schooled) pharmacy technicians can play a role in conducting some tasks of a CMR according to pharmacists, but rarely do in practice. A recent study on the implementation of CMRs in the German care setting also showed that pharmacists themselves believed that involving pharmacy technicians in some CMR tasks could improve the implementation of CMRs [31]. We therefore suggest delegating some tasks to (vocationally trained) pharmacy technicians. Especially in the first few steps of a CMR, such as the selection of patients and the gathering of important patient data during the pharmacotherapeutic anamnesis, technicians can limit the time spend by community pharmacists on CMRs.

Another potential method to increase efficiency for CMRs is to make more use of integrated information and communication technoclogy (ICT) systems, i.e. shared ICT systems between CP and GP teams. Although medication data and lab values of most patients have become available via a national electronic platform, the separate information systems of most pharmacies and general practices are not interconnected. Ideally, key clinical data needed for a CMR such as an overview of current medication, blood pressure or kidney function parameters as well as data generated in the course of a CMR should be readily available and shared between GP practices and pharmacies, observance to patients privacy.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the questionnaire sent out to all community pharmacies in the Netherlands by the Royal Dutch Association of Pharmacists (KNMP). The use of the CFIR framework as a basis for the questionnaire ensured that relevant aspects of implementation are included [20]. Using a questionnaire ensured that all pharmacists in the Netherlands could be approached by e-mail which increases the generalizability of the results.

This study reached a response rate of 14.8%. This response rate is too low to take our results as representative for the whole group of community pharmacists. Assuming that those who are most involved in CMR answered to our list, our results are likely to reflect the current best practice of CMR performance.

Lastly, the research covered a period during the COVID-19 pandemic, which might have influenced some of pharmacists’ responses. For example, pharmacists have conducted less CMRs in 2020 than in years prior to the pandemic, or might have experienced lack of time to be a more pronounced barrier due to staff shortages.

Conclusions

This study showed that community pharmacists in the Netherlands are more efficient in conducting CMRs compared with ten years ago, and some major barriers found back then such as the lack of a systematic approach and suboptimal selection criteria for patients have been overcome. Responding pharmacists believe (jointly) conducting CMRs improves their relationship with GPs and meets patient’s care needs. Lack of time and collaboration with medical specialists were the most important barriers for conducting CMRs. Our study advocates for the involvement of (vocationally educated) pharmacy technicians in the execution of CMRs, as well as the further development and integration of effective ICT solutions to make the process of conducting CMRs more time-efficient. Moreover, future studies should focus on the collaboration between community pharmacists and medical specialists by exploring the perspectives of both roles, in order to gain insight into possibilities to improve collaboration.

Data availability

Data used in this study is not publicly available.

Abbreviations

- CFIR:

-

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- CMR:

-

Clinical Medication Review

- CP:

-

Community Pharmacist

- Fte:

-

Full-Time Equivalent

- GP:

-

General Practitioner

- HCP:

-

Healthcare Provider

- ICT:

-

Information and Communication Technology

- PTAM:

-

Pharmacotherapeutic Audit Meeting

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

References

Eurostat. Self-Rep. Use Prescr. Med. Sex Age Educ. Attain. Level. 2022 (cited 2022 Apr 20). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/hlth_ehis_md1e/default/table?lang=en.

Bjerrum L, Rosholm JU, Hallas J, Kragstrup J. Methods for estimating the occurrence of polypharmacy by means of a prescription database. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;53:7–11.

Midão L, Giardini A, Menditto E, Kardas P, Costa E. Polypharmacy prevalence among older adults based on the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;78:213–20.

Khezrian M, McNeil CJ, Murray AD, Myint PK. An overview of prevalence, determinants and health outcomes of polypharmacy. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2020;11:2042098620933741.

Meraya AM, Dwibedi N, Sambamoorthi U. Polypharmacy and health-related quality of Life among US adults with arthritis, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2010–2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E132.

Viktil KK, Blix HS, Moger TA, Reikvam A. Polypharmacy as commonly defined is an indicator of limited value in the assessment of drug-related problems. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:187–95.

Leendertse AJ, Egberts ACG, Stoker LJ, van den Bemt PMLA, HARM Study Group. Frequency of and risk factors for preventable medication-related hospital admissions in the Netherlands. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1890–6.

Mast R, Ahmad A, Hoogenboom SC, Cambach W, Elders PJM, Nijpels G, et al. Amsterdam tool for clinical medication review: development and testing of a comprehensive tool for pharmacists and general practitioners. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:642.

KNMP. KNMP-Richtlijn medicatiebeoordeling (Internet). 2013 p. 22. https://www.knmp.nl/media/432.

Al-Babtain B, Cheema E, Hadi MA. Impact of community-pharmacist-led medication review programmes on patient outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Res Soc Adm Pharm RSAP. 2022;18:2559–68.

Chau SH, Jansen APD, van de Ven PM, Hoogland P, Elders PJM, Hugtenburg JG. Clinical medication reviews in elderly patients with polypharmacy: a cross-sectional study on drug-related problems in the Netherlands. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38:46–53.

Krska J, Cromarty JA, Arris F, Jamieson D, Hansford D, Duffus PR, et al. Pharmacist-led medication review in patients over 65: a randomized, controlled trial in primary care. Age Ageing. 2001;30:205–11.

Kwint HF, Faber A, Gussekloo J, Bouvy ML. Effects of medication review on drug-related problems in patients using automated drug-dispensing systems: a pragmatic randomized controlled study. Drugs Aging. 2011;28:305–14.

Huiskes VJB, Burger DM, van den Ende CHM, van den Bemt BJF. Effectiveness of medication review: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18:5.

Willeboordse F, Schellevis FG, Chau SH, Hugtenburg JG, Elders PJM. The effectiveness of optimised clinical medication reviews for geriatric patients: opti-Med a cluster randomised controlled trial. Fam Pract. 2017;34:437–45.

Niquille A, Lattmann C, Bugnon O. Medication reviews led by community pharmacists in Switzerland: a qualitative survey to evaluate barriers and facilitators. Pharm Pract. 2010;8:35–42.

Uhl MC, Muth C, Gerlach FM, Schoch G-G, Müller BS. Patient-perceived barriers and facilitators to the implementation of a medication review in primary care: a qualitative thematic analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19:3.

Bakker L, Kemper PF, Wagner C, Delwel GO, de Bruijne MC. A baseline assessment by healthcare professionals of Dutch pharmacotherapeutic care for the elderly with polypharmacy. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27:679–86.

Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. Brief over vastgestelde normen medicatiebeoordeling - Brief - Inspectie Gezondheidszorg en Jeugd (Internet). Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport; 2015 (cited 2022 Sep 27). https://www.igj.nl/publicaties/brieven/2015/05/8/vastgestelde-normen-medicatiebeoordeling.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

Beers MH, Ouslander JG, Rollingher I, Reuben DB, Brooks J, Beck JC. Explicit criteria for determining Inappropriate Medication use in nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1825–32.

Federation of Medical Specialists. Medicatiebeoordeling (MBO) - Richtlijn - Richtlijnendatabase (Internet). 2020 (cited 2022 Oct 11). https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/polyfarmacie_bij_ouderen/medicatiebeoordeling_mbo.html.

Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, Kennedy J, O’Mahony D. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Person’s prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to right treatment). Consensus validation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;46:72–83.

Levy HB, Marcus E-L, Christen C. Beyond the beers criteria: a comparative overview of explicit criteria. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:1968–75.

NHG. Polyfarmacie bij ouderen | NHG-Richtlijnen (Internet). 2020 (cited 2022 Apr 21). https://richtlijnen.nhg.org/multidisciplinaire-richtlijnen/polyfarmacie-bij-ouderen.

Van Ojik AL, Huisman-Baron M, Van Der Veen L, Jansen PAF, Brouwers JRBJ, Van Marum RJ, et al. Criteria Voor geneesmiddelkeuze: Kwetsbare ouderen en antidepressiva. Tijdschr Voor Ouderengeneeskunde. 2012;37:141–7.

Verduijn M, Leendertse A, Moeselaar A, de Wit N, van Marum R. Multidisciplinaire Richtlijn Polyfarmacie bij ouderen. Huisarts En Wet. 2013;56:414–9.

Michel DE, Tonna AP, Dartsch DC, Weidmann AE. Experiences of key stakeholders with the implementation of medication reviews in community pharmacies: a systematic review using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2022;18:2944–61.

Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297:831–41.

Renovanz M, Keric N, Richter C, Gutenberg A, Giese A. (Patient-centered care. Improvement of communication between university medical centers and general practitioners for patients in neuro-oncology). Nervenarzt. 2015;86:1555–60.

Michel DE, Tonna AP, Dartsch DC, Weidmann AE. Just a ‘romantic idea’? A theory-based interview study on medication review implementation with pharmacy owners. Int J Clin Pharm. 2023;45:451–60.

CCMO – Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects. Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO). 2006. https://english.ccmo.nl/investigators/legal-framework-for-medical-scientific-research/laws/medical-research-involving-human-subjects-act-wmo.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all community pharmacists for their participation in this research. Special thanks to Koray Kibar who developed the questionnaire during his internship.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Stijn Hogervorst was the executive researcher on this project and wrote the first draft of the paper. Marcel Adriaanse, Marcia Vervloet, Liset van Dijk, Martina Teichert, Jan-Jacob Beckeringh & Jacqueline Hugtenburg participated throughout the project, and helped with drafting the paper. Additionally, all authors contributed in writing the article and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In the Netherlands, completing a survey does not fall under the scope of the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act [32]. This law states that medical ethical review is only required when research involves human subjects and if people are being subjected to actions or if rules of behaviour are imposed on them. As our research consisted of a questionnaire that did not impose any rule or behaviour on our subjects, a medical ethics review of the study protocol was not required. Therefore, all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Pharmacists received an invitation letter by mail before the start of the questionnaire. Informed consent was asked prior to the questionnaire.

Consent for publication

This article does not contain any individuals persons data in any form, and therefore consent to publish is not required.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hogervorst, S., Adriaanse, M., Vervloet, M. et al. A survey on the implementation of clinical medication reviews in community pharmacies within a multidisciplinary setting. BMC Health Serv Res 24, 575 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11013-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11013-z