Abstract

Background

To evaluate the effect of pecking motions with faster upward speed on the dynamic cyclic fatigue resistance of nickel-titanium rotary instruments with different metallurgy.

Methods

Forty each of ProTaper Universal F3 (PTU) and ProTaper Gold F3 (PTG) instruments (size #30/.09) were equally divided into four groups. The test was performed using an 18-mm-long stainless steel artificial canal with a 5-mm radius of curvature, a 45° canal curvature and a 2-mm canal diameter. A downward speed of 100 mm/min was employed, while the upward speed was set at 100, 150, 200 or 300 mm/min. Time to failure (Tf), number of cycles to failure (Nf) and number of pecking motions to failure (Np) were recorded. Statistical analysis was performed using Kruskal Wallis and Mann–Whitney U tests for Tf, Nf, and Np (α = 0.05).

Results

The 100/300 mm/min group showed significantly higher Np values than the 100/100 mm/min group (p < 0.05), whereas there were no significant differences in Tf and Nf among the tested speed groups (p < 0.05) in either PTU or PTG. PTG exhibited significantly higher Tf, Nf, and Np than PTU (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Under the tested conditions, the fastest upward speed group showed significantly higher cyclic fatigue resistance, as demonstrated by larger Np, than the same speed group. PTG had significantly higher cyclic fatigue resistance than PTU in all groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Root canal cleaning and sha** with endodontic instruments is an essential phase of root canal treatment to create a space for three-dimensional disinfection and obturation [1]. Use of endodontic nickel-titanium (NiTi) instruments made from nitinol wire was pioneered by Walia et al. in 1988 [2]. In contrast with traditional stainless steel files, motorized NiTi rotary instruments are considered to facilitate root canal preparation with fewer procedural errors while maintaining the original root canal geometry [3,4,5].

However, separation of NiTi instruments remains one of the main complications in clinical endodontics despite advancements in metallurgy and design, which might occur at different stress/strain levels, either in the presence or absence of an obvious plastic deformation mark next to the fracture area [6,7,8]. Most instrument fractures arise due to cyclic fatigue, which is known to occur when the repeated compression/tension stresses gather through the curvature of the rotating instrument [10].

Laboratory cyclic fatigue tests are conducted in either static or dynamic mode with major differences in the axial motion [11,12,13,14]. The dynamic cyclic fatigue test simulates clinical conditions as it incorporates an axial motion (pecking motion), and is known to extend the fatigue resistance of the instruments by distributing the accumulated stress along the instrument [11,12,13,14].

The existing literature indicates that a same speed is widely adopted for the pecking motion in dynamic cyclic fatigue tests [11, 13,14,15,16,17,18]. However, it is possible that the withdrawal speed of the instrument during clinical instrumentation is faster than the insertion speed as a result of resistance release [12]. The manipulation style of the instruments during canal instrumentation is important as a preventive measure for intracanal instrument fracture [19]. It is therefore important to know how pecking motions with different axial speed patterns (such as same speed versus faster upward speed) affect the cyclic fatigue resistance of the instruments.

To the best of the authors' knowledge, there is no study investigating the effects of pecking motions with different axial speed patterns on the fatigue-reducing effect of the instruments. Hence, the aim of the present study was to examine the effect of different axial speed patterns on the dynamic cyclic fatigue resistance, using two NiTi rotary instruments with the same geometry but made of different NiTi alloys. The null hypothesis tested was that there would be no difference in time to failure (Tf), number of cycles to failure (Nf), and number of pecking motions to failure (Np) among the tested speed groups in each instrument system and also between the two instrument systems.

Materials and methods

G*Power (Version 3.1.9.6 for Mac OS X, Heine Heinrich Universität, Düsseldorf, Germany) was used for sample size estimation with an effect size of 0.75, α error of 0.05, and power of 0.95 in accordance with a previous study [12], and a total of 80 samples (n = 10, per group) was indicated.

Forty instruments each of ProTaper Universal F3 (PTU; #30/0.09; Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) and ProTaper Gold F3 (PTG; #30/0.09; Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) with a length of 25 mm were tested in this study. Inspection for observable production defects was performed at 25 × magnification under a dental operating microscope (MANI Dental Microscope Z; MANI, Utsunomiya, Japan).

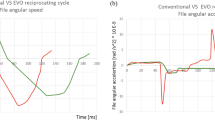

A dynamic cyclic fatigue test was performed using a customized testing device as previously described [12]. Briefly, the testing device contained a test stand with a movable stage (MH2-500N; IMADA, Toyohashi, Japan), where the handpiece of an X-Smart Plus motor (Dentsply Maillefer) was mounted (Fig. 1a). An 18-mm-long stainless steel artificial canal with a 45° angle of curvature, 5-mm radius of curvature, and 2-mm canal diameter was used (Fig. 1b, c). The downward and upward speeds of pecking motion in the same speed group were set at 100 mm/min (100/100 mm/min group) and served as a control. In the faster upward speed groups, the upward speed was set at 150, 200 and 300 mm/min (100/150, 100/200 and 100/300 mm/min groups, respectively). Each instrument type was equally divided into four groups (n = 10 each). The center of the curvature of the canal was 8 mm from the apex. The instruments were fixed at 15 mm in the artificial canal and then extended to the working length of 18 mm with 3 mm amplitude to simulate the pecking motion.

a Custom-made cyclic fatigue testing device. (1) movable test stand, (2) handpiece, (3) attached stainless steel artificial canal, (4) emergency stop button, (5) indicator, (6) setting button, (7) start and manual speed adjustment buttons and (8) stop button. b Stainless steel artificial canal (arrow). c Schematic diagrams of stainless steel artificial canal

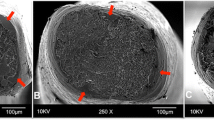

To reduce the frictional heat produced by the contact between the instruments and the artificial canal wall, silicone oil (KF-96-100CS; Shin-Etsu Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) was sprayed on each instrument before testing [12, 20]. A transparent glass plate was placed over the artificial canal. As recommended by the manufacturer, the instruments were operated at 300 rpm and 3 Ncm [21]. Until failure was noticed visually and audibly, Tf was recorded in seconds using a stopwatch (Time Keeper; Seiko, Tokyo, Japan). Videos were simultaneously documented with a digital single lens reflex camera (Nikon D5300; Nikon Imaging, Tokyo, Japan) throughout the experiment and Tf was reaffirmed with the recorded videos assessed by three examiners, including two blind examiners. The Nf was obtained by multiplying rpm and Tf (min) [12]. The Np was attained by the computerized data shown in the indicator on the test stand where videos were also taken simultaneously to ensure the accuracy of Np and fracture occurrence. The experiment was conducted at room temperature (23 ± 1.5 °C). The temperature was maintained by the air conditioning system, and an indoor digital thermometer/hygrometer was used to indicate the room temperature. Under a dental operating microscope, the fragment lengths were measured using a digital caliper (Mitutoyo, Kawasaki, Japan). Fractographic analysis of the fracture surface was performed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM; JSM-7900F Schottky Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at an acceleration voltage of 5 kV (n = 4 each).

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for normal distribution and Levene’s test for homogeneity of variance were used. As Tf, Nf, and Np were non-normally distributed, intergroup comparisons of these values were performed using the Kruskal Wallis test followed by the Mann–Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction. Differences in Tf, Nf, and Np between PTG and PTU were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Fragment length values showed normal distribution and homogeneous variance and thus were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance. All the statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v27 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) at a significance level of 0.05.

Results

The mean value of Tf obtained by 3 examiners was presented in Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 1. The median and interquartile ranges of Tf and Nf are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. There were no significant differences in Tf and Nf among groups with a different upward speed in either PTU or PTG (p > 0.05). PTG showed significantly higher Tf and Nf than PTU in all tested groups (p < 0.05).

The 100/300 mm/min group showed significantly higher Np compared with the 100/100 mm/min group in both PTU and PTG (p < 0.05) (Table 3). There were no significant differences in Np among the faster upward speed groups in either of the instrument systems (p > 0.05). PTG demonstrated a significantly higher Np than PTU in all tested speed groups (p < 0.05).

There was no significant difference in fragment length among the tested groups or between PTU and PTG (p > 0.05; Table 4), and 57.5% of PTU instruments and 62.5% of PTG instruments fractured during downward movement.

Representative SEM images (Fig. 2) show typical features of cyclic fatigue failure, including crack initiating areas and dimples.

Discussion

The effect of pecking motions with the same upwards and downwards speeds and faster upward speeds on the dynamic cyclic fatigue resistance of instruments with similar designs and sizes was investigated in the present study. Despite Tf and Nf exhibited non-significant differences, there were significant differences in Np between the 100/100 mm/min group and the 100/300 mm/min group in each instrument system. Thus, the first hypothesis, that there would be no difference in Tf, Nf, and Np among the tested speed groups in each instrument system, was partly rejected. The second hypothesis, that there would be no difference in Tf, Nf, and Np between the two instrument systems, was also rejected because significant differences in Tf, Nf, and Np were observed between the two instrument systems in all tested groups.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first study investigating the effect of different axial speed patterns on the fatigue reduction during NiTi rotary instrumentation. The automated cyclic fatigue testing device was used to produce constant speed and movement with stroke motion. No consensus on clinical insertion and withdrawal speeds is available, and the practical withdrawal speeds may vary from clinician to clinician. Thus, we used the different faster upward speeds at certain values to understand the behaviors of the tested instruments relating to cyclic fatigue resistance, in comparison with same speed. As it is essential to retain the geometric features of the canal to standardize the experimental condition, we used the stainless steel artificial canal. It has been reported that the instruments’ size and cross-sectional design are among the influencing factors on cyclic fatigue resistance [22, 23]. To eliminate such variables, PTU and PTG instruments with identical geometrical designs and sizes [24] were selected in the present study.

This study employed Np as a factor that influences dynamic cyclic fatigue resistance [25], in addition to Tf and Nf, which are widely used to evaluate cyclic fatigue resistance [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18, 26,27,28,29]. Np is also considered an important variable that can help estimate how many times a rotating instrument can pass through the highest flexure area by resisting the stresses before breakage. Moreover, groups with different upward speeds will exhibit different Np values even when the duration of the instrumentation, and thus Tf and Nf, is similar among groups. For these reasons, Np was employed to evaluate the dynamic cyclic fatigue resistance in the present study.

It has been reported that the faster pecking motions with the same upwards and downwards speeds significantly improved the fatigue life of the instruments [25]. Besides, our previous study showed that a dynamic cyclic fatigue test with faster upward speed significantly extended the fatigue resistance of the continuous rotary instruments in contrast to the static cyclic fatigue test [12]. In spite of the non-significant differences in Tf and Nf among the tested speed groups for each instrument system, the 100/300 mm/min group exhibited significantly greater Np in both PTU and PTG compared with the same speed group in the present study. These outcomes are inconsistent with the results reported by a previous study, which may be due to the application of different methodologies [25].

The finding of the present study indicates that the instruments in the fastest upward speed group with the largest speed difference between downward and upward movements travelled significantly more frequently in and out of the artificial curved canal. Thus, it seems reasonable to suppose that the instruments in the 100/300 mm/min group withstood the repeated tensile and compressive stresses loaded into a shorter cycle, indicating higher resistance to failure than the same speed group. This can be explained by the mechanism by which the fastest upward speed enhanced the quickest release of the stress accumulated in the rotating instrument before the next downward movement.

PTG instruments showed significantly higher Tf, Nf, and Np than those of PTU instruments in all tested groups. These results (Tf and Nf) are in agreement with several previous studies [21, 29,30,31]. The difference between PTG and PTU instruments may be attributable to the metallurgy of the alloys. A previous study has reported that PTG exhibits two-phase transformation behavior (austenite – R-phase – martensite), and the austenite finish temperature is 50.1 ± 1.7 °C for PTG and 21.2 ± 1.9 °C for PTU [21]. Hence, it can be assumed that PTG and PTU are mainly composed of the martensite/R-phase and austenite phases, respectively, at both room and body temperature [21]. Thus, the experimental room temperature used in this study may have had no significant impact despite the fact that the modulus of elasticity of PTG might be greater at the body temperature. PTG is reported to be more flexible and suffer less stress, which increases cyclic fatigue resistance compared to PTU with comparable geometric designs and sizes when a similar strain is applied [21], which is consistent with our findings. The effect of the different handle lengths, 13 mm in PTU and 11 mm in PTG, on the cyclic fatigue resistance of the instruments remains unexamined yet. However, this may not have significantly affected the results of the present study.

Non-significant differences in the fragment length among the tested speed groups and between the instrument systems in the present study may imply similar bending movements of the instruments [12]. The instruments fractured during both downward and upward movements in the present study, suggesting that the instruments experienced stress at the curvature during both movements as long as they have contact areas with the canal walls. The lower fracture rate during the upward movement could be related to the immediate stress-releasing mechanism that just starts beyond the curvature, where the instrument size and the canal size are indirectly proportional, and the contact area decreases in size during the upward movement. Additionally, it seems reasonable to suppose that the instruments had lesser compression and tension cycles in the same period of time when the upward speed is increased.

In the present study, the cyclic fatigue resistance against the stresses produced along the axis of the artificial curved canal was measured by Np in the same axis, which can be a reliable indicator for cyclic fatigue resistance because it is in accordance with the defined mechanism of the cyclic fatigue fracture [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. However, one limitation of this study is that only two types of instruments were examined. Moreover, no universal consensus for cyclic fatigue resistance testing is accessible so far, thus, the different methodologies have widely been adopted [10, 32]. Pecking speeds have an effect on torque and screw-in force of the instruments [33], suggesting that pecking speed setting is a factor that poses methodological consideration. Besides, the lack of clinical adaptability of the artificial stainless steel canal is another limitation of this study. Because various factors including its geometric features and surface roughness, real-time torque, screw-in force, and reaction torque in the stainless steel artificial canal may differ from the natural root canal. Hence, the feasible clinical impact of faster upward speeds on the cyclic fatigue resistance should be further investigated attentively, incorporating the effect of upward pecking speeds on those factors. It should also be noted that the variations in geometric characteristics may alter the instruments' resistance to cycle fatigue [34]. Therefore, further research should be done to validate the findings of this study. Additionally, it has been noted that the cyclic fatigue resistance of NiTi instruments considerably decreased when used repeatedly in clinical settings [35, 36]. Hence, further study is suggested to determine if the different axial speed patterns improve the cyclic fatigue resistance of repeatedly used instruments.

Conclusions

Within the limitations of the present study, the fastest upward speed group with the largest speed difference displayed significantly higher dynamic cyclic fatigue resistance, as demonstrated by the larger Np, than the same speed group. PTG exhibited significantly higher cyclic fatigue resistance than PTU in all groups.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Tf :

-

Time to failure

- Nf :

-

Number of cycles to failure

- Np :

-

Number of pecking motions to failure

- PTG:

-

ProTaper Gold

- PTU:

-

ProTaper Universal

- NiTi:

-

Nickel-titanium

References

Schilder H. Filling root canals in three dimensions. J Endod. 2006;32:281–90.

Walia H, Brantley WA, Gerstein H. An initial investigation of the bending and torsional properties of nitinol root canal files. J Endod. 1988;14:346–51.

Peters OA. Current challenges and concepts in the preparation of root canal systems: a review. J Endod. 2004;30:559–67.

Sonntag D, Guntermann A, Kim SK, Stachniss V. Root canal sha** with manual stainless steel files and rotary Ni–Ti files performed by students. Int Endod J. 2003;36:246–55.

Cheung GSP, Liu CSY. A retrospective study of endodontic treatment outcome between nickel-titanium rotary and stainless steel hand filing techniques. J Endod. 2009;35:938–43.

Cheung GS, Peng B, Bian Z, Shen Y, Darvell BW. Defects in ProTaper S1 instruments after clinical use: fractographic examination. Int Endod J. 2005;38:802–9.

Peng B, Shen Y, Cheung GSP, **a TJ. Defects in ProTaper S1 instruments after clinical use: longitudinal examination. Int Endod J. 2005;38:550–7.

Sattapan B, Nervo GJ, Palamara JE, Messer HH. Defects in rotary nickel-titanium files after clinical use. J Endod. 2000;26:161–5.

Shen Y, Cheung GS, Peng B, Haapasalo M. Defects in nickel-titanium instruments after clinical use. Part 2: fractographic analysis of fractured surface in a cohort study. J Endod. 2009;35:133–6.

Hülsmann M, Donnermeyer D, Schäfer E. A critical appraisal of studies on cyclic fatigue resistance of engine-driven endodontic instruments. Int Endod J. 2019;52:1427–45.

De-Deus G, Vieira VT, da Silva EJ, Lopes H, Elias CN, Moreira EJ. Bending resistance and dynamic and static cyclic fatigue life of Reciproc and WaveOne large instruments. J Endod. 2014;40:575–9.

Thu M, Ebihara A, Maki K, Miki N, Okiji T. Cyclic fatigue resistance of rotary and reciprocating nickel-titanium instruments subjected to static and dynamic tests. J Endod. 2020;46:1752–7.

Lopes HP, Elias CN, Vieira MV, Siqueira JF Jr, Mangelli M, Lopes WS. Fatigue life of Reciproc and Mtwo instruments subjected to static and dynamic tests. J Endod. 2013;39:693–6.

Keleş A, Eymirli A, Uyanık O, Nagas E. Influence of static and dynamic cyclic fatigue tests on the lifespan of four reciprocating systems at different temperatures. Int Endod J. 2019;52:880–6.

Elnaghy AM, Elsaka SE, Elshazli AH. Dynamic cyclic and torsional fatigue resistance of TruNatomy compared with different nickel-titanium rotary instruments. Aust Endod J. 2020;46:226–33.

Özyürek T, Keskin NB, Furuncuoğlu F, İnan U. Comparison of cyclic fatigue life of nickel-titanium files: an examination using high-speed camera. Restor Dent Endod. 2017;42:224–31.

Bulem UK, Kececi AD, Guldas HE. Experimental evaluation of cyclic fatigue resistance of four different nickel-titanium instruments after immersion in sodium hypochlorite and/or sterilization. J Appl Oral Sci. 2013;21:505–10.

Palma PJ, Messias A, Cerqueira AR, Tavares LD, Caramelo F, Roseiro L, et al. Cyclic fatigue resistance of three rotary file systems in a dynamic model after immersion in sodium hypochlorite. Odontology. 2019;107:324–32.

Parashos P, Messer HH. Rotary NiTi Instrument fracture and its consequences. J Endod. 2006;32:1031–43.

Nishijo M, Ebihara A, Tokita D, Doi H, Hanawa T, Okiji T. Evaluation of selected mechanical properties of NiTi rotary glide path files manufactured from controlled memory wires. Dent Mater J. 2018;37:549–54.

Hieawy A, Haapasalo M, Zhou H, Wang ZJ, Shen Y. Phase transformation behavior and resistance to bending and cyclic fatigue of ProTaper Gold and ProTaper Universal instruments. J Endod. 2015;41:1134–8.

Gambarini G. Cyclic fatigue of ProFile rotary instruments after prolonged clinical use. Int Endod J. 2001;34:386–9.

Oh SR, Chang SW, Lee Y, Gu Y, Son WJ, Lee W, et al. A comparison of nickel-titanium rotary instruments manufactured using different methods and cross-sectional areas: ability to resist cyclic fatigue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:622–8.

Deari S, Zehnder M, Al-Jadaa A. Effect of dentine cutting efficiency on the lateral force created by torque-controlled rotary instruments. Int Endod J. 2020;53:1153–61.

Zubizarreta-Macho Á, Mena Álvarez J, Albaladejo Martínez A, Segura-Egea JJ, Caviedes Brucheli J, Agustín-Panadero R, et al. Influence of the pecking motion frequency on the cyclic fatigue resistance of endodontic rotary files. J Clin Med. 2019;9:45.

Duque JA, Bramante CM, Duarte MA, Alcalde MP, Silva EJ, Vivan RR. Cyclic fatigue resistance of nickel-titanium reciprocating instruments after simulated clinical use. J Endod. 2020;46:1771–5.

Ahn S, Ha JH, Kwak SW, Kim HC. Advancement of mechanical properties of nickel-titanium rotary endodontic instruments by spring machining on the file shaft. Materials (Basel). 2020;13:5246.

Fukumori Y, Nishijyo M, Tokita D, Miyara K, Ebihara A, Okiji T. Comparative analysis of mechanical properties of differently tapered nickel-titanium endodontic rotary instruments. Dent Mater J. 2018;37:667–74.

Martins JN, Silva EJ, Marques D, Ginjeira A, Fernandes FM, De Deus G, et al. Influence of kinematics on the cyclic fatigue resistance of replicalike and original brand rotary instruments. J Endod. 2020;46:1136–43.

Kaval ME, Capar ID, Ertas H. Evaluation of the cyclic fatigue and torsional resistance of novel nickel-titanium rotary files with various alloy properties. J Endod. 2016;42:1840–3.

Özyürek T, Yılmaz K, Uslu G. The effects of autoclave sterilization on the cyclic fatigue resistance of ProTaper Universal, ProTaper Next, and ProTaper Gold nickel-titanium instruments. Restor Dent Endod. 2017;42:301–8.

Plotino G, Grande NM, Cordaro M, Testarelli L, Gambarini G. A review of cyclic fatigue testing of nickel-titanium rotary instruments. J Endod. 2009;35:1469–76.

Maki K, Ebihara A, Kimura S, Nishijo M, Tokita D, Okiji T. Effect of different speeds of up-and-down motion on canal centering ability and vertical force and torque generation of nickel-titanium rotary instruments. J Endod. 2019;45:68–72.

Al-Sudani D, Grande NM, Plotino G, Pompa G, Di Carlo S, Testarelli L, Gambarini G. Cyclic fatigue of nickel-titanium rotary instruments in a double (S-shaped) simulated curvature. J Endod. 2012;38:987–9.

Aydin C, Inan U, Tunca YM. Comparison of cyclic fatigue resistance of used and new RaCe instruments. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:e131–4.

Pessoa OF, Silva JM, Gavini G. Cyclic fatigue resistance of rotary NiTi instruments after simulated clinical use in curved root canals. Braz Dent J. 2013;24:117–20.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (No. 19K18987) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: MT, AE, KM, TO. Acquisition of data: MT, MSK, MN, TN, Analysis and interpretation of data: MT, SK, AE, TO. Drafting of manuscript: MT. Critical revision: TO. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 1.

Mean value of Tf (seconds) obtained by 3 examiners.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Thu, M., Ebihara, A., Maki, K. et al. Effect of different axial speed patterns on cyclic fatigue resistance of rotary nickel-titanium instruments. BMC Oral Health 22, 617 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-022-02639-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-022-02639-8