Abstract

Background

The prevalence of obesity is considered to be increased worldwide. Lack of mineral elements is one of the essential side effects of bariatric surgery as a trending treatment for obesity. We aimed to assess zinc deficiency among morbidly obese patients before and following different types of bariatric surgical procedures.

Methods

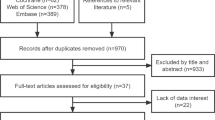

In the present retrospective cohort study, 413 morbidly obese patients (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 40 kg/m2 or BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 with a complication or risk factor, e.g., diabetes mellitus) were enrolled who received bariatric surgery, aged between 18 and 65 years old, and had a negative history of active consumption of alcohol and illicit drugs. Patients were assigned into three groups of bariatric surgeries: mini-gastric bypass, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), and sleeve gastrectomy (SG). We recorded baseline clinical and demographic characteristics and zinc serum levels during the preoperative and postoperative follow-up periods at three, six, and 12 months after the operation.

Results

All patients with a mean age of 40.57 ± 10.63 years and a mean preoperative BMI of 45.78 ± 6.02 kg/m2 underwent bariatric surgery. 10.2% of the bariatric patients experienced zinc deficiency before the surgery, and 27.1% at 1 year after the surgery. The results showed that 27.7% of mini-gastric bypass patients, 29.8% of RYGB, and 13.3% of SG experienced zinc deficiency 12 months following surgery. We observed no statistical differences in the preoperative and postoperative zinc deficiency between different types of surgeries.

Conclusion

A high prevalence of preoperative zinc deficiency among morbidly obese patients who underwent bariatric surgery was observed, which increased during the postoperative periods. We recommend assessing zinc serum levels and prescribing zinc supplements before the bariatric operation to alleviate the prevalence of zinc deficiency after the operation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity, as one of the most crucial health issues worldwide, is considered a modifiable and preventable risk factor for many diseases. The increased rate of obesity raises the mortality and morbidity rates in populations. The main consequences are cardiovascular diseases, cerebrovascular accidents and strokes,, and cancer types [1]. Approximately 600 million people are obese globally, and the prevalence of obesity in Iran was reported by 21.4% in 2019 [2]. Bariatric surgery is a trend for obesity treatment recently. Several types of bariatric operationsare classified into restrictive procedures, including sleeve gastrectomy (SG), malabsorptive procedures, such as biliopancreatic diversion with or without a duodenal switch, and combined procedures, like Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and mini-gastric bypass [3].

The trace elements, including zinc, copper, selenium, and iron, playan essential role in biomedical pathways for cell function and metabolism in cells [4]. Zinc is a catalytic component of many metalloenzymesand transcription factors found in all body tissues, fluids, and secretions [5]. The zinc serum levels are reduced in obesity, indicating the correlation of zinc deficiency and obesity-related complications such as insulin resistance [6]. The serum zinc levels are the main pool of available zinc in the human body. Therefore, zinc deficiency could affect zinc hemostasis [7]. The zinc deficiency can cause hair loss, diarrhea, glossitis, nail dystrophy, hypogonadisms in males, infertility, and anemia, delayed wound healing, skin lesion, and taste alteration [8]. The lack of micronutrients reported in most studies is one of the common complications after bariatric surgery. One of them is the four-year follow-up of 65 obese patients after bariatric surgery that showed basal deficiencies in obese patients, which is increased after bariatric surgery [9].

This study aimed to assess the zinc deficiency in morbidly obese patients after bariatric surgeries and its changes according to the types of surgical procedures among the Iranian population.

Main text

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study at the obesity center of RasoulAkramHospital, Tehran, Iran, fromDecember2018 to December2019. We recruited 413 morbidly obese patients (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 40 kg/m2 or BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 with a complication or risk factor, e.g., DM) who underwent bariatric surgery, aged between 18 and 65 years old, and did not actively consume alcohol and illicit drugs. Patients who had a history of bariatric surgery were excluded. The Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences approved the present study (Ethics code: IR.IUMS.REC 1396.31866).

We assigned the patients into three groups according to the type of bariatric surgery (mini-gastric bypass, RYGB, and SG). We recorded zinc serum levels during the preoperative period and follow-up measurements at three, six, and 12 months after the surgery. The reference value for zinc serum levels is 70-120 μg/dl [10]. Baseline clinical and demographic features were also recorded on a checklist.

At the first postoperative visit (2–3 weeks after the operation), we encouraged the patients to take multivitamin and mineral supplementations postoperatively (one tablet orally daily), which contained30 mg zinc as zinc oxide per tablet alongside other vitamins and micronutrients, presented in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

We performed statistical analyses using IBM SPSS statistics version 19. Continuous variables were demonstrated as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and categorical values as percentages or absolute values. To compare continuous variables, we used ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis test based on the assumptions of the former. In case the ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis test met the significant levels, we performed Tukey post hoc test. We made a comparison of categorical values by Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. We considered 2-tailed p values of < 0.05 statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

Four hundred thirteen (413) patients met the inclusion criteria, and their demographic information is shown in Table 2. In Total, all patients with a mean age of 40.57 ± 10.63 years and a mean preoperative BMI of 45.78 ± 6.02 kg/m2underwent bariatric surgery. Significantly more patients were female (334, 83.3%), and more underwent mini-gastric bypass than RYGB or SG (289, 94, and 30, respectively). The ANOVA test for age between surgical groups was not significant (P-value: 0.413). The frequency of comorbidities, including hypertension, DM type II, hyperlipidemia, and hypothyroidism, were summarized in Table 1. Hyperlipidemia was the most common comorbidity in all patients (188/413).

Zinc serum levels and zinc deficiency

The mean preoperativezinc plasma concentration was 89.96 ± 21.4 μg/dl. Thezincserum level after surgery was significantly decreased in patients (P-value< 0.001), with statistically significant differences between the preoperative period and the six and 12 months after the operation, as well as between the third postoperative month and the six and 12 months after the operation. There was an association between BMI groups and zinc serum levels (P-value: 0.044), with a statistical difference between 40 ≤ BMI ≤ 50 and BMI > 50 groups. Furthermore, the association between sex and zinc serum levels was significant (P-value: 0.038). The data weresummarized in Table 3. There was no association between zinc serum levels and any comorbidities. However,there was a significant association between impaired FBS, DM type II, and zinc deficiency (P-value: 0.027, and 0.047, respectively). The zinc plasma concentration was shown in Table S1 (Supplementary file: Tables) based on the type of bariatric procedures. At 12 months of surgery, the zinc serum level presented significantly lower in the mini-gastric bypass compared to the other types of surgeries. We compared zinc deficiency between groups of bariatric surgery before and after the operation, shown in Table S2 (Supplementary file: Tables)). The results showed that at 12 months after operation, 27.7% of the patients who underwent mini-gastric bypass, 29.8% of RYGB, and 13.3% of SG experienced zinc deficiency. However, no significant difference in zinc deficiency between different types of surgery was observed.

Discussion

In the current study, we demonstrated that bariatric patients tended to show a high proportion of zinc deficiency increased from 10.2% in the preoperative period to 27.1% at 1 year after the surgery. There are reports which presented a high prevalence of zinc deficiency among obese patients during the preoperative period [11,12,13,14,15]. Previous studies have represented the following reasons for explaining zinc deficiency in obese patients: 1. The chronic inflammation in obese patients promotes metallothionein and zinc-copper transporter expression, resulting in the accumulation of the metal in hepatocytes and adipocytes, responsible for decreased zinc serum levels [16], 2. Inadequate intake of zinc resources with high concentrations of this micronutrient might account for zinc deficiency [17].

Furthermore, the prevalence of zinc deficiency is considered to be increased following bariatric surgery [13]. It has been revealed that 4–9% of bariatric patients experience zinc deficiency preoperatively and 20–24% after 18 months of bariatric operation [18,19,20,21,22]. A small-sized randomized controlled trial of severe and morbidly obese female patients who underwent RYGB reported a significant decrease in zinc absorption from 32.3 to 13.6% after 6 months of RYGB [20]. Decreased zinc absorption has been described by reducing the acidic environment following RYGB and SG [23].

However, Rojas et al. noted that zinc plasma levels seemed to increase at 6 months after RYGB among severe or morbidly obese women. They attributed such an increase in zinc plasma levels to reducing inflammation presented in their patients after the surgery. Nonetheless, they mentioned the “size of the exchangeable zinc pool” as a suitable zinc status parameter, which significantly decreased after RYGB [23].

We have shown that preoperative zinc serum levels were significantly lower among bariatric patients with 40 ≤ BMI < 50 kg/m2, but we did not find an association between zinc deficiency and BMI. Consistently, Mohammadi et al. presented that morbidly obese patients with BMI > 50 kg/m2have lower zinc serum levels while there was no relation between zinc deficiency and an increasing BMI [15]. However, it has been reported that zinc serum levels before bariatric surgery seem to be not related to BMI [13, 24, 25]. Differences in:1) Cultural and geographical factors, which could affect zinc deficiency, 2) study designs, 3) Data distribution in BMI groups, and 4. dietary intake or nutritional habits might potentially account for such contrast findings between reports [15].

In our study, significantly lower serum zinc concentrations and higher proportions of zinc deficiency were observed in female patients before the surgery. Compared to the male gender, higher rates of zinc deficiency in females could be attributed to different food patterns. Our findings were in agreement with the Mohammadi et al. study, which reported a similar pattern of zinc deficiency in women patients while they found no significant association between zinc deficiency and sex [15].

Comparing zinc deficiency among different surgical techniques, we found that 27.7% of the patients who received mini-gastric bypass, 29.8% of RYGB, and 13.3% of SG experienced zinc deficiency 12 months after surgery. It can be also interpreted that zinc deficiency increased 18% among mini-gastric bypass and 19.2% among RYGB patients from the preoperative period to 12 months after the surgery. However, no significant difference was observed in zinc deficiency between groups of bariatric surgery. Similar to our findings, Ferraz et al. observed no significant difference in zinc deficiency between RYGB and SG after 12 months of surgery (25.6% vs. 26.6%, respectively). Nevertheless, they presented a substantial difference between the surgeries at 24 months of follow-up (RYGB: 30% vs. SG: 6.6%, P-value< 0.05) [10]. Consistently, a higher prevalence of zinc deficiency among RYGB patients compared to SG patients following 12 months of operation has been reported (40.7% vs. 18.8%, respectively) [13]. Concerning such a significant difference, some explanations have been offered: 1. RYGB results in food transit deviation, 2. SG optimizes gastric and proximal intestinal emptying time, which helps the nutrients maintain more prolonged contact with the jejunum and proximal ileum and leads to a better adhesion to vitamin supplementation [10].

It has been reported that zinc deficiency could cause different disorders, including skin disorders (e.g. bullous dermatitis, psoriasiform and eczematous lesions), and be fatal in severe cases [5, 26, 27]. In addition, the deficiency of this micronutrient might contribute to poor recovery during the postoperative period [15], so preoperative baseline assessment and correction of zinc deficiency could improve its prevalence in the postoperative period. Previous studies suggested that zinc deficiency might be prevented by administration of zinc supplementations after bariatric surgery [19]. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) guidelines has recommended taking a daily multivitamin supplementation following obesity surgery to achieve dietary reference intakes of zinc, which equal 8–11 mg per day [28]. Despite the fact that our multivitamin and mineral supplementations contained 30 mg of elemental zinc, we observed a high prevalence of zinc deficiency among our patients at the end of the study period. However, the average zinc serum levels were within the normal range in our patients during the postoperative period.

Collectively, in the present cohort study, we assessed the zinc status in a population of morbidly obese patients during the pre- and post-bariatric periods and compared zinc deficiency between different groups of bariatric surgeries within the first year of operation. We observed a high prevalence of preoperative zinc deficiency among morbidly obese patients who underwent bariatric surgery, which increased during the postoperative period. Besides, we found that mini-gastric bypass and RYGB, compared to SG, showed higher zinc deficiency rates at the end of the 12-month follow-up. However, we recommend an assessment of zinc serum levels and prescribing zinc supplementation before bariatric surgery to alleviate the prevalence of zinc deficiency after the operation.

Strengths and limitations

Our study’s strengths included: 1. cohort study design and the large study population, 2. we compared different bariatric operations regarding zinc deficiency during the 12 months of follow-up that helped us extend the currently available data concerning zinc status in different bariatric surgical procedures. However, we encountered some limitations. First, we were unsure of whether patients take their multivitamin and mineral supplementations on a daily and regular basis after the surgery. Second, we did not evaluate confounding variables, including albumin and C-reactive protein (CRP) serum levels, which might affect the status of trace elements. Third, different distribution of patients among bariatric surgery categories, as well as the small number of patients in SG group, which could explain no significant difference in zinc deficiency between bariatric surgery groups. Forth, some modifiable variables might change the zinc serum levels, including dietary intakes and food habits. Fifth, patients’ compliance with the multivitamin and mineral supplementations following the operation was not recorded, which could possibly have an impact on zinc serum levels.

To track the exact changes in the prevalence of zinc deficiency among different types of bariatric surgeries during the pre- and postoperative period, we suggest further prospective studies with long-term follow-ups, assigning a similar number of patients into each group of surgery and matching study participants regarding nutritional habits, monitoring the patients to receive their multivitamin and micronutrient supplementations regularly after the operation, and evaluating the albumin and CRP serum levels as potential confounders.

Availability of data and materials

The authors agree with sharing, co**, and modifying the data used in this article, even for commercial purposes. The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- RYGB:

-

Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass

- SG:

-

Sleeve Gastrectomy

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- CRP:

-

C-Reactive Protein

References

Papamargaritis D, Aasheim ET, Sampson B, le Roux CW. Copper, selenium and zinc levels after bariatric surgery in patients recommended to take multivitamin-mineral supplementation. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2015;31:167–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.09.005.

Vaisi-Raygani A, Mohammadi M, Jalali R, Ghobadi A, Salari N. The prevalence of obesity in older adults in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:1–9.

Kermansaravi M, Ebrahimian M, Delbari D, Khamoushi S, Kabir A. Role of bariatric surgery in treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Contemp Med Sci. 2017;3:286–94.

Hung K-C, Wu Z-F, Chen J-Y, Chen I-W, Ho C-N, Lin C-M, et al. Association of Serum Zinc Concentration with preservation of renal function after bariatric surgery: a retrospective pilot study. Obes Surg. 2020;30(3):867–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-04260-1.

Tuerk MJ, Fazel N. Zinc deficiency. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2009;25(2):136–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOG.0b013e328321b395.

Rios-Lugo MJ, Madrigal-Arellano C, Gaytán-Hernández D, Hernández-Mendoza H, Romero-Guzmán ET. Association of Serum Zinc Levels in overweight and obesity. Biol Trac Elem Res. 2020;198(1):51–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-020-02060-8.

Olesen R, Hyde T, Kleinman J, Smidt K, Rungby J, Larsen A. Obesity and age-related alterations in the gene expression of zinc-transporter proteins in the human brain. Transl Psychiatr. 2016;6:e838.

Mahawar KK, Bhasker AG, Bindal V, Graham Y, Dudeja U, Lakdawala M, et al. Zinc deficiency after gastric bypass for morbid obesity: a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2017;27(2):522–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-016-2474-8.

de Luis DA, Pacheco D, Izaola O, Terroba MC, Cuellar L, Martin T. Zinc and copper serum levels of morbidly obese patients before and after biliopancreatic diversion: 4 years of follow-up. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(12):2178–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-011-1647-y.

Ferraz ÁAB, Carvalho MR, Siqueira LT, Santa-Cruz F, Campos JM. Micronutrient deficiencies following bariatric surgery: a comparative analysis between sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2018;45:e2016.

Madan AK, Orth WS, Tichansky DS, Ternovits CA. Vitamin and trace mineral levels after lap a roscopic gastric by pass. Obes Surg. 2006;16:603–6.

Ernst B, Thurnheer M, Schmid SM, Schultes B. Evidence for the necessity to systematically assess micronutrient status prior to bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2009;19(1):66–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-008-9545-4.

Sallé A, Demarsy D, Poirier AL, Lelièvre B, Topart P, Guilloteau G, et al. Zinc deficiency: a frequent and underestimated complication after bariatric surgery. Obesity Surg. 2010;20(12):1660–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-010-0237-5.

Lefebvre P, Letois F, Sultan A, Nocca D, Mura T, Galtier F. Nutrient deficiencies in patients with obesity considering bariatric surgery: a cross-sectional study. Surg Obes Related Dis. 2014;10(3):540–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2013.10.003.

Mohammadi FG, Zabetian TF, Pishgahroudsari M, Mokhber S, Pazouki A. High prevalence of zinc deficiency in Iranian morbid obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery. J Minim Invas Surg Sci. 2015;4:e33347.

de Luis DA, Pacheco D, Izaola O, Terroba MC, Cuellar L, Cabezas G. Micronutrient status in morbidly obese women before bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Related Dis. 2013;9(2):323–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2011.09.015.

Westerterp-Plantenga M, Wijckmans-Duijsens N, Verboeket-Van de Venne W, De Graaf K, Van het Hof K, Weststrate J. Energy intake and body weight effects of six months reduced or full fat diets, as a function of dietary restraint. Int J Obes. 1998;22:14–22.

Balsa JA, Botella-Carretero JI, Gómez-Martín JM, Peromingo R, Arrieta F, Santiuste C, et al. Copper and zinc serum levels after derivative bariatric surgery: differences between Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and biliopancreatic diversion. Obes Surg. 2011;21(6):744–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-011-0389-y.

Gletsu-Miller N, Wright BN. Mineral malnutrition following bariatric surgery. Adv Nutr. 2013;4(5):506–17. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.113.004341.

Ruz M, Carrasco F, Rojas P, Codoceo J, Inostroza J, Basfi-fer K, et al. Zinc absorption and zinc status are reduced after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a randomized study using 2 supplements. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(4):1004–11. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.111.018143.

Ruz M, Cavan KR, Bettger WJ, Thompson L, Berry M, Gibson RS. Development of a dietary model for the study of mild zinc deficiency in humans and evaluation of some biochemical and functional indices of zinc status. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53(5):1295–303. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/53.5.1295.

Moizé V, Andreu A, Flores L, Torres F, Ibarzabal A, Delgado S, et al. Long-term dietary intake and nutritional deficiencies following sleeve gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in a mediterranean population. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(3):400–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2012.11.013.

Rojas P, Carrasco F, Codoceo J, Inostroza J, Basfi-fer K, Papapietro K, et al. Trace element status and inflammation parameters after 6 months of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obesity Surg. 2011;21(5):561–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-011-0368-3.

Cominetti C, Garrido AB, Cozzolino SMF. Zinc nutritional status of morbidly obese patients before and after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a preliminary report. Obes Surgery. 2006;16(4):448–53. https://doi.org/10.1381/096089206776327305.

Hyun TH, Barrett-Connor E, Milne DB. Zinc intakes and plasma concentrations in men with osteoporosis: the rancho Bernardo study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(3):715–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/80.3.715.

Desirello G, Crovato F. Scopinaro N, editors. Biliopancreatic diversion: an experimental clinical model of the relation between zinc and the skin Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1990;117(10):729–30.

Weismann K, Wadskov S, Mikkelsen HI, Knudsen L, Christensen KC, Storgaard L. Acquired zinc deficiency dermatosis in man. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114(10):1509–11. https://doi.org/10.1001/archderm.1978.01640220058015.

Mechanick JI, Kushner RF, Sugerman HJ, Gonzalez-Campoy JM, Collazo-Clavell ML, Guven S, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & bariatric surgery medical guidelines for clinical practice for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient. Surg Obes Related Dis. 2010;6:112.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to show our gratitude to the Rasool Akram Medical Complex Clinical Research Development Center (RCRDC), Iran University of Medical Sciences for its technical and editorial assists.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: FS; Acquisition of data: MH, DA, MO, MR, DE; Analysis and interpretation of data: FS, MR, DE; Drafting of the manuscript: FS, DE;Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors; Statistical analysis: MP, DA, MO; Administrative, technical, and material support and study supervision: FS, DE; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences approved the present study (Ethics code: IR.IUMS.REC 1396.31866). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients signed inform consent before participating in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1

. Zinc serum levels among bariatric surgery groups during the pre- and postoperative periods. Table S2. Zinc deficiency among bariatric surgery groups during the pre- and postoperative periods.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Soheilipour, F., Ebrahimian, M., Pishgahroudsari, M. et al. The prevalence of zinc deficiency in morbidly obese patients before and after different types of bariatric surgery. BMC Endocr Disord 21, 107 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-021-00763-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-021-00763-0