Abstract

Background

High levels of childhood trauma (CT) have been observed in adults with mental health problems. Herein, we investigated whether self-esteem (SE) and emotion regulation strategies (cognitive reappraisal (CR) and expressive suppression (ES)) affect the association between CT and mental health in adulthood, including depression and anxiety symptoms.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional study of 6057 individuals (39.99% women, median age = 34 y), recruited across China via the internet, who completed the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), Self-esteem Scale (SES), and Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ). Multivariate linear regression analysis and bias-corrected percentile bootstrap methodologies were used to assess the mediating effect of SE, and hierarchical regression analysis and subgroup approach were performed to examine the moderating effects of emotion regulation strategies.

Results

After controlling for age and sex, we found that (1) SE mediated the associations between CT and depression symptoms in adulthood (indirect effect = 0.05, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.04–0.05, 36.2% mediated), and CT and anxiety symptoms in adulthood (indirect effect = 0.03, 95% CI: 0.03–0.04, 32.0% mediated); (2) CR moderated the association between CT and SE; and (3) ES moderated the association between of CT and mental health in adulthood via SE, and such that both the CT-SE and SE-mental health pathways were stronger when ES is high rather than low, resulting the indirect effect was stronger for high ES than for low ES.

Conclusions

These findings suggested that SE plays a partially mediating role in the association between CT and mental health in adulthood. Furthermore, ES aggravated the negative effect of CT on mental health in adulthood via SE. Interventions such as emotional expression training may help reduce the detrimental effects of CT on mental health.

Trial registration

The study was registered on http://www.chictr.org.cn/index.aspx and the registration number was ChiCTR2200059155.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Epidemiological studies show that the rise of intense competition and survival pressure has resulted in a growing number of adults suffering from mental health problems [1]. Childhood trauma (CT), defined as emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, or emotional and physical neglect before the age of 16, has been extensively researched and established as a significant contributor to the development and deterioration of mental health in adulthood [2,3,4,5,6]. Studies have found that 28.9% of patients with psychiatric disorders have reported experiencing CT, and the effects of CT can persist throughout their lives [3]. A meta-analysis of the available literature suggests that experiencing any type of abuse may increase the risk of depression and anxiety symptoms in adulthood by over two-fold [7]. Given its impact on public health, it is important to further study the psychological symptomology of the effects of CT on mental health.

Bowlby J’s Attachment Theory states that adolescents develop co** mechanisms based on the influences of their parents and family environment to deal with stress, but experiences of adversity during this formative period can disturb the development of a healthy self-concept and secure attachments [8, 9]. Cumulative and severe exposure to adversity can lead to the development of poor self-concept, low self-esteem (SE), negative self-evaluation, and social withdrawal [10]. Prior research supports the theoretical link between the effects of CT and SE on mental health. A study of college students in Turkey found that SE acted as a mediator between CT and depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms in early adulthood [11]. In addition, three other studies conducted on children and adolescents showed that the negative influence of CT on mental health was mediated by lower SE [12,13,14]. These findings provide evidence for the important role of SE in the association between CT and mental health outcomes.

Previous literature has converged on the idea that cognition plays a crucial role in the development of depression and anxiety disorders [15]. Cognitive emotion regulation refers to attempts to respond to ongoing experiential demands with a range of emotions in a socially tolerable and sufficiently flexible manner [16, 17]. This can be characterized by two dimensions: cognitive reappraisal (CR) (adaptive emotion strategy, i.e., reinterpreting emotional events to alter the perceptions of their meaning and reduce emotional responses) and expressive suppression (ES) (maladaptive emotion strategy, i.e., suppressing outward expression of emotions that will occur or is occurring) [18]. Beck AT suggested that emotion regulation abilities are developed in early life [19] and adversity experiences in early life may make individuals more vulnerable to mental health difficulties in adulthood by altering stress response and emotion regulation systems [20], which play a key role in the development of mental health difficulties [21]. Cognitive theories put maladaptive emotion strategy at the core of depression and anxiety disorders.

Failure to effectively regulate emotions has been found to be strongly associated with the onset of mental health problems [22]. Empirical evidence provided support for the mediation role of cognitive emotion regulation strategies in the association between CT and mental health problems in various populations, including clinical sample [16], college student sample [23], children and adolescents [24, 25]. Individuals who have experienced CT are prone to subsequent emotion-regulation problems [26,27,28,29], ultimately leading to mental health problems, including depression and anxiety symptoms in later life [30, 31]. Besides the mediated effect, a growing body of research has revealed that emotion regulation moderates the association between CT and mental health problems in youth, and that the two interacting strategies, CR and ES, have different effects on mental health outcomes [32]. A lower use of CR and an increased use of ES were associated with high levels of depression and anxiety symptoms [33, 34]. In addition, Huang et al. revealed that Qi-stagnation constitution (QSC) partially mediated the association between CT on depression symptomology, and emotion dysregulation moderated the path between QSC and depression symptomology in college students [35].

Many studies have verified the mediating role of SE in the association between CT and mental health problems in college students [11], children and adolescents [12,13,14]. However, few studies have investigated it in adults. In addition, there is inconsistency in the role (as mediator or moderator) of emotion regulation strategies in previous research. CT may affect mental health problems via SE, but what role do emotion regulation strategies play in this process and under what circumstances do emotion regulation strategies influence the association between CT and mental health problems are remained to answer.

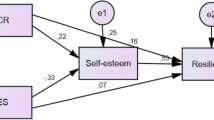

To address the limitations in previous research, the current study aims to estimate the prevalence of lifetime CT reported by a large sample of healthy adults from across China, and the impact of SE and emotion regulation strategies on the association between CT and mental health outcomes. The study proposed the following hypotheses: (1) SE mediates the association between CT and mental health in adulthood; (2) CR moderates the association between CT and mental health in adulthood via SE, such that both the CT-SE and SE-mental health paths will be weaker when CR is high rather than low; and (3) ES will moderate the correlation between CT and mental health in adulthood via SE, such that both CT-SE and SE-mental health paths will be stronger when ES is high rather than low. As shown in Fig. 1, we constructed a moderated mediation model to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the association between CT and mental health, the mediating role of SE, and the moderating role of emotion regulation.

Methods

Participants and procedure

This cross-sectional study recruited participants who responded to the questionnaire delivered through a link on the **gdong (JD) Insight platform (https://survey.jd.com/) across China from May 1, 2022, to May 30, 2022. The questionnaire contained questions on sociodemographic characteristics, anxiety, depression, and somatic symptoms, insomnia, emotion regulation, social support, SE, and CT. The inclusion criteria were: (1) 18 y of age or older; (2) Internet access via a smartphone or computer, and independent completion of the questionnaire; and (3) normal vision and hearing. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) severe or unstable physical disorder; (2) evidence of current or prior head injury, CNS disease, or other ICD-10 disorders; (3) history of substance abuse within six months before screening; (4) cognitive impairment; and (5) history of taking antipsychotics and long-acting injectable antipsychotics within the past two weeks. Eventually, 6057 individuals were included in the analysis. All data were collected online, and informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Hospital Affiliated Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (TJ-IRB20220408). The registration number for this trial was ChiCTR2200059155. The URL of the publicly accessible registered website is: http://www.chictr.org.cn/index.aspx.

Measures

Childhood trauma

CT was assessed using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), an internationally accepted retrospective self-reported measure of five types of trauma experienced before age 16: emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, or emotional and physical neglect [36]. The CTQ consists of 28-item, rated on a 5-point frequency scale (1 = never true to 5 = very often true), and summed to yield a total score ranging from 5 to 25 for each type of trauma, with higher scores indicating greater severity [36]. The Chinese version of the CTQ has previously demonstrated good reliability and validity [49]. We followed the recommendations of Preacher and Hayes (2008) [48] and calculated the confidence intervals of the lower and upper bounds to test whether the indirect effects were significant.

The moderated mediation effects of emotion regulation strategies were tested using path analytic methods accomplished through hierarchical regression analysis [50] and subgroup approach [51]. In all analyses, age and sex were entered as covariates [52]. First, we standardized all variables to reduce the potential effects of multicollinearity [50]. Second, we tested the first- and second-stage moderated mediated models outlined by MacKinnon [53], which can be divided into the following three steps. Step 1: The least squares technique was used with control variables entered as block 1 (age and sex). Step 2: The main effects are entered as block 2. Step 3: The moderators enter block 3. Finally, following the protocol of Edwards and Lambert (2007) [46], we calculated the simple effects under the mean (i.e., mean-centered), low (i.e., one SD below the mean), and high (i.e., one SD above the mean) levels of CR/ES. Differences in simple effects were computed by subtracting the effects for low CR/ES from those for high CR/ES, and indirect effects were calculated by multiplying the simple effects in both the first- and second-stage.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 6057 participants, comprising 2422 women (39.99%) and 3635 men (60.01%), were included in the analysis of the present study. The median (IQR) age of the participants was 34 (30–40) y. Pearson correlation analysis indicated that age was negatively associated with depression (r = -0.13, p < 0.001) and anxiety symptoms (r = -0.10, p < 0.001); however, the levels of depression and anxiety symptoms showed no significant difference based on sex (p > 0.05).

Bivariate correlations

Pearson correlation analysis was used to test the bivariate correlations of all variables. As shown in Table 1, CT had a significantly negative association with SE (r = -0.41, p < 0.001) and a positive association with depression (r = 0.31, p < 0.001) and anxiety symptoms (r = 0.28, p < 0.001), while SE had a significantly negative correlation with depression (r = -0.35, p < 0.001) and anxiety symptoms (r = -0.30, p < 0.001). According to the associations among Cohen’s Standard, d, and r [54], all correlations showed small effects, except for the correlation between CT and SE, which showed a medium effect.

Multivariate linear regression analysis was performed to determine the associations between variables, and the results are presented in Additional file 1. After controlling for age and sex, higher CT was associated with lower SE (β = -0.19, p < 0.001), higher depression (β = 0.13, p < 0.001), and higher anxiety symptoms (β = 0.10, p < 0.001). Additionally, SE was negatively correlated with depression (β = -0.30, p < 0.001) and anxiety symptoms (β = -0.21, p < 0.001).

Mediating effect of SE on the link between CT and mental health in adulthood

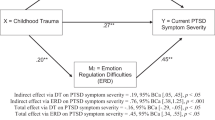

Two hypothetical mediation models were produced to test the mediating role of SE in the association between CT and mental health in adulthood in the context of SEM, for which the results are displayed in Table 2; Fig. 2. As shown in Table 2 and Panel A of Fig. 2, SE mediated the effect of CT on depression symptoms. Based on 5000 bootstrap resamples, the indirect path from CT to depression symptoms was significant (indirect effect = 0.05, 95% confidence interval [CI]:0.04–0.05, 36.2% mediated). Similarly, as shown in Table 2 and Panel B of Fig. 2, SE mediated the effect between CT and anxiety symptoms, and the indirect path from CT to anxiety symptoms was also significant (indirect effect = 0.03, 95% CI:0.03–0.04, 32.0% mediated). Taken together, these results suggest that SE mediated both the links between CT and depression symptoms as well as between CT and anxiety symptoms, suggesting that individuals with CT are more likely to have lower SE, which is associated with more depression and anxiety symptoms in adulthood.

Moderating role of emotion regulation strategies in the link between CT and mental health in adulthood via SE

As shown in Table 3, although CR moderated the CT-SE path (p < 0.001), it did not moderate either SE-depression symptoms (p > 0.05) or SE-anxiety symptoms (p > 0.05) paths. Additionally, there were no significant differences in the simple effects of the first- and second-stage as well as the indirect path (p > 0.05) (Table 4). In contrast, ES moderated not only the CT-SE path (p < 0.001), but also SE-depression symptoms (p < 0.001) and SE-anxiety symptoms (p < 0.001) (Table 5). Moreover, the moderated mediation effects of high and low levels of ES for the CT-SE-depression/anxiety symptom models were significantly different, as shown in Table 6.

For the CT–SE–depression symptoms model, the first- and second- stage simple effects for low ES were − 0.22 (p < 0.01) and − 0.17 (p < 0.001), resulting in an indirect effect of 0.04 (p < 0.001). For high ES, the first- and second-stage simple effects were − 0.18 (p < 0.001) and − 0.34 (p < 0.001), yielding an indirect effect of 0.06 (p < 0.001). Furthermore, the results of the comparison between low and high ES indicated that the first-stage simple effect did not differ significantly (0.04, p > 0.05); however, the second-stage simple effect was stronger for high ES than for low ES (0.17, p < 0.01), and the indirect effect comparison between them was also statistically different (0.03, p < 0.05).

For the CT–SE–anxiety symptoms model, the first- and second-stage simple effects for low ES were − 0.22 (p < 0.01) and − 0.12 (p < 0.001). Thus, the indirect effect for low ES was 0.03 (p < 0.001). For high ES, the first- and second-stage simple effects were − 0.18 (p < 0.001) and − 0.25 (p < 0.001), respectively. Hence, the indirect effect for high ES was 0.04 (p < 0.001). In addition, the results of the comparison between low and high ES suggest that the first-stage simple effects for high and low ES did not differ significantly (0.04, p > 0.05); however, the second-stage simple effect was stronger for high ES than for low ES (0.13, p < 0.01). Finally, the indirect effect comparison was found to be statistically different (0.02, p < 0.05).

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to ensure that the above findings were not influenced by potential confounders including age and sex. For this purpose, all analyses were repeated without the above covariates, as shown in Additional files 2 and 3. There were no meaningful changes in the significance or magnitude of the above findings, indicating their robustness.

Discussion

While several studies have indicated the mediating role of SE between CT and mental health problems, and more studies have addressed the impact of emotion regulation strategies on mental health trajectory, few have linked both in adulthood. The present study therefore presents evidence for the mediating role of SE in a large sample population and finds a moderating effect of ES on the association between CT and mental health in adulthood via SE.

In line with Hypothesis 1, our results showed that SE partially mediated the association between CT and depression and anxiety symptoms in adulthood. According to attachment theory, exposure to abuse in childhood can lead to diminished perceptions of oneself, as well as emotional problems that threaten future psychological health [55]. In other words, abused children are less likely to perceive themselves as valuable and important and have less ability to deal with emotional problems compared to those who do not experience abuse [56, 57]. Our results are consistent with past research showing that university students with traumatic experiences have lower total SES scores [11, 58]. In addition, as a state of being self-satisfied without considering oneself inferior or superior, a decline in SE may induce mental health problems [58]. A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies covering 77 studies on depression and 18 on anxiety symptoms confirmed the negative effect of SE on depression and anxiety symptoms levels [59]. Moreover, another study indicated that low SE predicted subsequent levels of depression in adolescence and young adulthood [60]. Taken together with the results of the present study, this suggests a potential mechanism through which CT affects mental health in adulthood.

In addition, the results of the hierarchical regression analysis showed that ES moderated the CT-SE, SE-depression symptoms, and SE-anxiety symptom pathways, whereas CR moderated only the CT-SE pathway. However, the comparison between low and high CR/ES indicated no significant differences in the simple effects of the CT-SE path. The inconsistent results of the hierarchical regression analysis and subgroup approach may be due to the following reasons. First, research conducted within each subgroup has a lower statistical power than the full sample [61]. Second, studies using subgroup approach often form subgroups by dichotomizing the continuous moderating variables. Compared to hierarchical regression analysis, this approach results in the loss of information, and often leads to biased parameter estimates, further reducing statistical power [62, 63]. Finally, as shown in Additional files 4 and 5, both ES and CR are not normally distributed, and it is not appropriate to divide groups simply using mean-centered data. Taken together, these results partially support hypothesis 2 and fully support hypothesis 3.

As an adaptive emotion regulation strategy, CR diminishes negative effects by reinterpreting one’s thinking about the situation that causes negative emotions [22]. Although both CR and ES have mood-reducing functions, individuals with high levels of CR may be more likely to respond to adverse events with problem-focused co** rather than avoidance, and this problem-focused co** strategy is usually effective, especially in Western cultures [64]. In addition, another study suggested that CR could buffer the negative effects of CT on mental health in patients with depression disorder [16]. However, in the present study, we found that CR moderated the association between CT and SE, whereas no moderated mediation effect of CR on the association between CT and mental health in adulthood was found. We therefore surmised that these inconsistent results may be attributed to the relatively small sample size of previous studies, as well as the differences in ethnicity [64].

Furthermore, the results demonstrated that ES moderated the association between CT and mental health in adulthood via SE, such that the indirect path was stronger when ES was high rather than low, indicating that ES aggravated the negative effect of CT on mental health in adulthood via SE. ES generally refers to altering the way a person’s behavior reacts to events that elicit emotions by suppressing their outward expression [65]. As a reaction-focused emotion regulation strategy [18], the use of ES appears to be less effective at reducing negative emotions [65], which in turn is associated with negative mental health outcomes [66]. Thus, in line with our results, ES is generally considered a maladaptive emotional regulation strategy and a risk factor for depression and anxiety symptoms, whereas CR is considered an adaptive strategy, and is associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety symptoms [66]. The more often ES was used to regulate emotions in the face of negative emotional stimuli, the lower the SE of those who experienced CT, which is related to depression and anxiety symptoms in adulthood. Although individuals temporarily inhibit the outward expression of negative emotions with good intentions, there is generally no evidence to suggest that it can help alleviate negative emotional experiences from CT in the long term [18, 52, 67].

Moreover, several studies have focused on the moderating role of culture and ethnicity in the association between ES and mental health outcomes, demonstrating that ES is generally detrimental to mental health outcomes across cultures. Although Asian individuals have fewer negative outcomes correlated with ES compared to Western individuals [68,69,70], ES nevertheless remains highly prevalent among the Chinese population, as emotional control and restraint are considered virtues in Chinese culture [18, 68]. In the present study, we also found that the use of ES in individuals who experienced CT aggravated the negative effects on mental health in adulthood via SE, which is in line with previous research on emotion regulation in Asian youth [71]. Thus, individuals may benefit from develo** healthy emotion regulation profiles that include less suppression during adulthood.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the underlying moderated mediation mechanisms of emotion regulation strategies on mental health among those who experienced CT. These results have several practical implications. For example, children should be given more care to avoid psychological symptoms in adulthood, and intervention programs should consider the mediating role of SE between CT and mental health in adulthood. In addition, though emotional control and restraint are considered virtues in Chinese culture, our study suggests that ES is harmful to mental health because it can aggravate the negative effect of CT on mental health in adulthood via SE. Encouraging emotional expression and release may reduce the impact of CT on mental health.

However, several limitations must be addressed in future research. First, the information was collected via online surveys, which are more subjective than the results of a structured interview, which is limited by its brief and nondiagnostic nature. Second, CT recall bias may be possible, which may affect the reliability of retrospective assessments of traumatic experiences in children. Finally, as a cross-sectional study, it was difficult to establish a causal association between the variables, and further longitudinal studies are recommended to determine the causal association between them.

Conclusion

In summary, the results of this study suggest that SE partially mediates the association between CT and mental health in adulthood. Furthermore, ES aggravates the negative effect of CT on mental health in adulthood via SE. Future interventions and policy recommendations aiming to reduce the detrimental effects of CT should consider the role of emotion regulation.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Childhood trauma

- SE:

-

Self-esteem

- CR:

-

Cognitive reappraisal

- ES:

-

Expressive suppression

- QSC:

-

Qi-stagnation constitution

- JD:

-

**gdong

- CTQ:

-

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire

- ERQ:

-

Emotional Regulation Questionnaire

- SES:

-

Self-Esteem Scale

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

- GAD-7:

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- SEM:

-

Structural equation modeling

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- CI:

-

Confidence interval.

References

Lin L, Wang HH, Lu C, Chen W, Guo VY. Adverse childhood experiences and subsequent chronic Diseases among Middle-aged or older adults in China and Associations with demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2130143.

Hovens JG, Wiersma JE, Giltay EJ, van Oppen P, Spinhoven P, Penninx BW, et al. Childhood life events and childhood trauma in adult patients with depressive, anxiety and comorbid disorders vs. controls. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122(1):66–74.

Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(5):378–85.

Mandelli L, Petrelli C, Serretti A. The role of specific early trauma in adult depression: a meta-analysis of published literature. Childhood trauma and adult depression. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(6):665–80.

Nanni V, Uher R, Danese A. Childhood maltreatment predicts unfavorable course of illness and treatment outcome in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(2):141–51.

Spinhoven P, Elzinga BM, Hovens JG, Roelofs K, Zitman FG, van Oppen P, et al. The specificity of childhood adversities and negative life events across the life span to anxiety and depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(1–2):103–12.

Li M, D’Arcy C, Meng X. Maltreatment in childhood substantially increases the risk of adult depression and anxiety in prospective cohort studies: systematic review, meta-analysis, and proportional attributable fractions. Psychol Med. 2016;46(4):717–30.

Kim Y, Lee H, Park A. Patterns of adverse childhood experiences and depressive symptoms: self-esteem as a mediating mechanism. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57(2):331–41.

Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: attachment. New York: Basic Books; 1982.

Liu RT, Kleiman EM, Nestor BA, Cheek SM. The hopelessness theory of Depression: a quarter century in review. Clin Psychol (New York). 2015;22(4):345–65.

Berber Celik C, Odaci H. Does child abuse have an impact on self-esteem, depression, anxiety and stress conditions of individuals? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66(2):171–8.

Arslan G. Psychological maltreatment, emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents: the mediating role of resilience and self-esteem. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;52:200–9.

Greger HK, Myhre AK, Klockner CA, Jozefiak T. Childhood maltreatment, psychopathology and well-being: the mediator role of global self-esteem, attachment difficulties and substance use. Child Abuse Negl. 2017;70:122–33.

Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal trajectories of self-system processes and depressive symptoms among maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Child Dev. 2006;77(3):624–39.

John Kingsbury Frost. (1922–1990): a composite of memories. Diagn Cytopathol. 1991; 7(2):220–222.

Huh HJ, Kim KH, Lee HK, Chae JH. The relationship between childhood trauma and the severity of adulthood depression and anxiety symptoms in a clinical sample: the mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation strategies. J Affect Disord. 2017;213:44–50.

McRae K, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation. Emotion. 2020;20(1):1–9.

Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(2):348–62.

Beck AT. The evolution of the cognitive model of depression and its neurobiological correlates. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(8):969–77.

Buss C, Entringer S, Moog NK, Toepfer P, Fair DA, Simhan HN, et al. Intergenerational transmission of maternal childhood maltreatment exposure: implications for fetal Brain Development. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(5):373–82.

Baumeister D, Lightman SL, Pariante CM. The interface of stress and the HPA Axis in behavioural phenotypes of Mental Illness. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2014;18:13–24.

Buhle JT, Silvers JA, Wager TD, Lopez R, Onyemekwu C, Kober H, et al. Cognitive reappraisal of emotion: a meta-analysis of human neuroimaging studies. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24(11):2981–90.

Zhang F, Liu N, Huang C, Kang Y, Zhang B, Sun Z, et al. The relationship between childhood trauma and adult depression: the mediating role of adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;48:101911.

Choi JY, Oh KJ. Cumulative childhood trauma and psychological maladjustment of sexually abused children in Korea: mediating effects of emotion regulation. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38(2):296–303.

Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(6):706–16.

Shipman K, Zeman J, Penza S, Champion K. Emotion management skills in sexually maltreated and nonmaltreated girls: a developmental psychopathology perspective. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12(1):47–62.

Shipman K, Edwards A, Brown A, Swisher L, Jennings E. Managing emotion in a maltreating context: a pilot study examining child neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29(9):1015–29.

Burns EE, Jackson JL, Harding HG. Child maltreatment, emotion regulation, and posttraumatic stress: the impact of emotional abuse. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2010;19.

Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Adaptive co** under conditions of extreme stress: Multilevel influences on the determinants of resilience in maltreated children. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2009; 2009(124):47–59.

Domes G, Schulze L, Bottger M, Grossmann A, Hauenstein K, Wirtz PH, et al. The neural correlates of sex differences in emotional reactivity and emotion regulation. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31(5):758–69.

McRae K, Ochsner KN, Mauss IB, Gabrieli JJD, Gross JJ. Gender differences in emotion regulation: an fMRI study of cognitive reappraisal. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2008;11(2):143–62.

Lee M, Lee ES, Jun JY, Park S. The effect of early trauma on north korean refugee youths’ mental health: moderating effect of emotional regulation strategies. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112707.

Betts J, Gullone E, Allen JS. An examination of emotion regulation, temperament, and parenting style as potential predictors of adolescent depression risk status: a correlational study. Br J Dev Psychol. 2009;27(Pt 2):473–85.

Weinberg A, Klonsky ED. Measurement of emotion dysregulation in adolescents. Psychol Assess. 2009;21(4):616–21.

Huang H, Song Q, Chen J, Zeng Y, Wang W, Jiao B, et al. The role of Qi-Stagnation Constitution and emotion regulation in the Association between Childhood Maltreatment and Depression in Chinese College Students. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:825198.

Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Manual. The Psychological Corporation San Antonio: 1998; 1998.

He J, Zhong X, Gao Y, **ong G, Yao S. Psychometric properties of the chinese version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF) among undergraduates and depressive patients. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;91:102–8.

Cheung CS, Pomerantz EM, Wang M, Qu Y. Controlling and Autonomy-Supportive parenting in the United States and China: Beyond Children’s reports. Child Dev. 2016;87(6):1992–2007.

Wang Q, Pomerantz EM, Chen H. The role of parents’ control in early adolescents’ psychological functioning: a longitudinal investigation in the United States and China. Child Dev. 2007;78(5):1592–610.

Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965.

Shen ZL, Cai TS. Disposal to the 8th item of Rosenberg self-esteem scale (Chinese version). Chinese Mental Health Journal.2008; 22(9).

Wang W, Bian Q, Zhao Y, Li X, Wang W, Du J, et al. Reliability and validity of the chinese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(5):539–44.

Lowe B, Decker O, Muller S, Brahler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46(3):266–74.

von Oertzen T. Power equivalence in structural equation modelling. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2010;63(Pt 2):257–72.

Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(4):422–45.

Edwards JR, Lambert LS. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: a general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol Methods. 2007;12(1):1–22.

Umeh KF. Ethnic inequalities in doctor-patient communication regarding personal care plans: the mediating effects of positive mental wellbeing. Ethn Health. 2019;24(1):57–72.

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–91.

Taylor AB, MacKinnon DP, Tein JY. Tests of the three-path mediated effect. Organizational Research Methods. 2008; 11(2).

Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple Regression/Correlation analysis for the behavioral Sciences. 3rd ed. Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ; 2003.

MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:83–104.

Preston T, Carr DC, Hajcak G, Sheffler J, Sachs-Ericsson N. Cognitive reappraismotional suppression, and depressive and anxiety symptoms in later life: The moderating role of gender. Aging Ment Health. 2021:1–9.

MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104.

Rosnow RL, Rosenthal R. Computing contrasts, effect sizes, and countermills on other people ’ s published data: general procedures for research consumers. Psychol Methods. 1996;1.

Toth SL, Cicchetti D, Macfie J, Maughan A, VanMeenen K. Narrative representations of caregivers and self in maltreated pre-schoolers. Attach Hum Dev. 2000;2(3):271–305.

Cole PM, Luby J, Sullivan MW. Emotions and the development of Childhood Depression: bridging the gap. Child Dev Perspect. 2008;2(3):141–8.

Hymowitz G, Salwen J, Salis KL. A mediational model of obesity related disordered eating: the roles of childhood emotional abuse and self-perception. Eat Behav. 2017;26:27–32.

Ozakar Akca S, Oztas G, Karadere ME, Yazla Asafov E. Childhood trauma and its relationship with suicide probability and Self-Esteem: A case study in a university in Turkey. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021.

Sowislo JF, Orth U. Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2013;139(1):213–40.

Orth U, Robins RW, Roberts BW. Low self-esteem prospectively predicts depression in adolescence and young adulthood. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95(3):695–708.

Cohen J. The cost of dichotomization. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1983;7.

Maxwell SE, Delaney HD. Bivariate median splits and spurious statistical significance. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113.

Stone-Romero EF, Anderson LE. Relative power of moderated multiple regression and the comparison of subgroup correlation coefficients for detecting moderating effects. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1994;79.

Bartley CE, Roesch SC. Co** with daily stress: the role of conscientiousness. Pers Individ Dif. 2011;50(1):79–83.

John OP, Gross JJ. Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. J Pers. 2004;72(6):1301–33.

Cutuli D. Cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression strategies role in the emotion regulation: an overview on their modulatory effects and neural correlates. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014;8:175.

Butler EA, Egloff B, Wilhelm FH, Smith NC, Erickson EA, Gross JJ. The social consequences of expressive suppression. Emotion. 2003;3(1):48–67.

Butler EA, Lee TL, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation and culture: are the social consequences of emotion suppression culture-specific? Emotion. 2007;7(1):30–48.

Butler EA, Lee TL, Gross JJ. Does expressing your emotions raise or lower your blood pressure? The answer depends on Cultural Context. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2009;40(3):510–7.

Roberts NA, Levenson RW, Gross JJ. Cardiovascular costs of emotion suppression cross ethnic lines. Int J Psychophysiol. 2008;70(1):82–7.

Soto JA, Perez CR, Kim YH, Lee EA, Minnick MR. Is expressive suppression always associated with poorer psychological functioning? A cross-cultural comparison between European Americans and Hong Kong Chinese. Emotion. 2011;11(6):1450–5.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients and their family for participation and referring physicians.

Funding

The study was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2020kfyXGYJ002), Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province of China (2022CFB276) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (82090034).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YY and PCF designed this research. MHW and ML designed the outline of the manuscript. CL, YX, CHH and XS provided advice on the design of the questionnaire and the collection of data. CL analyses the data and the wrote the first draft of the manuscript. PCF, HZ and YY revised the whole manuscript. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript and approved the submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Hospital Affiliated Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (TJ-IRB20220408). The registration number for this trial was ChiCTR2200059155. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed informed consent to participate.

Consent for publication

All patients signed informed content for publication.

Competing interests

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

12888_2023_4719_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary Material 1: Additional file 1 Multiple linear regression results for testing the association between CT/SE and mental health. Additional file 2 Coefficient estimates for the moderated mediation model for cognitive reappraisal. Additional file 3 Coefficient estimates for the moderated mediation model for expressive suppression. Additional file 4 The distribution of cognitive reappraisal. Additional file 5 The distribution of expressive suppression.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., Fu, P., Wang, M. et al. The role of self-esteem and emotion regulation in the associations between childhood trauma and mental health in adulthood: a moderated mediation model. BMC Psychiatry 23, 241 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04719-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04719-7