Abstract

Background

Life satisfaction (LS) is part of a positive psychological feeling that protects individuals from a physical decline in old age. A healthy lifestyle, including physical activity (PA) and a healthy diet, such as the intake of fruits and vegetables (F&V), can lead to a better experience of LS in older adults. However, the association between PA and F&V intake habits when occurring together in older adults is still unclear for LS. The study aimed to investigate the combined association of PA and F&V intake on LS among a cohort of older Taiwanese adults.

Methods

Five waves of population-based data gathered by the Taiwan Longitudinal Survey on Aging between 1999 and 2015 were analyzed. The year 1999 was set as the baseline, and the number of respondents was 4,440. The independent variables included the frequency, duration, and intensity of PA and the frequency of F&V intake. LS was assessed by using the Life Satisfaction Index. We performed generalized estimating equations (GEE) analysis with adjustment for covariates of health behaviors and health indicators.

Results

After adjusting for confounders, model 1 showed that moderate and high-PA levels significantly correlated with LS (odds ratio [OR] = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.12–1.79) and OR = 1.74, 95% CI = 1.50–2.02). Moreover, high-F&V intake significantly correlated with LS (OR = 2.07, 95% CI = 1.69–2.53). Regarding the combined association shown in model 2, compared with both the low PA and F&V intake group, there were significantly higher LS in the both-high-group (OR = 4.69, 95% CI = 3.49–6.31), only-high-F&V intake (OR = 2.87, 95% CI = 2.14–3.85), only-high-PA (OR = 2.48, 95% CI = 1.74–3.52).

Conclusions

Our findings show the significant combined association of PA and F&V intake on LS among older adults. In addition, older adults who engaged in higher frequency, duration, and intensity of daily PA combined more than seven times a week of F&V intake had significantly higher LS than those who only engaged in low PA or only intake less F&V. Adopting multiple healthy behaviors in daily life is a safe and effective approach to promote LS among older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Worldwide, there is an increasingly aging population. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the number of people aged over 65 years will reach two billion by 2050. About 25% of older adults present a mental disorder during their lifetime, which exerts a considerable health burden [1]. Accordingly, there is a need for cross-disciplinary actions comprising the provision of health and evidence-based adoption of life behaviors, including physical activity (PA) and nutritional intake [2,3,4].

It is generally recognized that positive well-being has three dimensions: positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction (LS) [5]. Previous studies have shown an association between happiness and healthier and longer lives [6,7,8,9]. The LS indicator determines an individual's positive emotions and assesses how well an individual's expectations of life match their actual state [10]. Measures of life satisfaction are more stable than positive emotions because they reflect subjective feelings of success and happiness [10, 11]. LS protects individuals against the physical decline in old age [12]. In addition, LS was significantly and negatively associated with morbidity in healthy and ill populations [9] and was associated with lower morbidity and mortality in community-dwelling older individuals [8].

There is increasing evidence that primary health-related behaviors, including regular PA and wholesome dietary patterns, may improve the intrinsic abilities of older adults [1]. Healthy life behaviors, including PA and good nutrition, can allow older adults to achieve their goals, feel capable, maintain a sense of identity, and experience improved life satisfaction (LS) [13]. Among older adults, PA is positively correlated with LS [14, 15]. However, while PA is vital for health, most older adults do not meet the PA recommendations [16]. Moreover, fruit and vegetable (F&V) intake is positively correlated with mental and physical health as well as LS [17], especially among older adults [18,19,20]. Furthermore, F&V intake is negatively correlated with the risk of depressive symptoms and cognitive decline [21, 22]. Research has consistently demonstrated a positive correlation between fruit and vegetable (F&V) intake and mental health especially depression symptoms. For example, vegetables vitamins A, B, C, fibers, plant-based food correlated negatively with depression [23, 24]. These findings collectively support the idea that increased F&V intake may reduce depression risk through various nutritional and neurological mechanisms. However, the long-term and combined association of PA and F&V intake on LS remain unclear. Life satisfaction is particularly important for the mental health of older adults [25]. Therefore, physical activity, dietary intake, and life satisfaction are all highly relevant issues to the health of older adults. Thus, we aimed to examine the combined associations of PA and F&V intake on LS among middle-aged and older Taiwanese adults.

Methods

Data and Sample

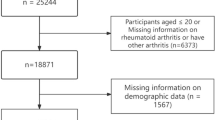

The data were retrieved from the Taiwan Longitudinal Survey on Aging (TLSA) survey data from 1999 to 2015, a joint initiative of the Taiwan Health Promotion Administration and the Population Studies Center of the University of Michigan [26]. The TLSA represents the Taiwan region with a long-term follow-up period, high completion rate, and relocation case tracking [26]. The first wave of TLSA was conducted in 1989, with waves of surveys conducted every 3–4 years and the sixth wave of surveys completed in 2015. The participants were selected using a stratified, multi-stage, random sampling method. This database comprised data collected from the household-registered population aged over 60 years who were registered in 311 Taiwanese townships and cities, sampled neighbors from 56 townships and urban areas, and selected two adults aged over 60 years from each sample as interview cases. In addition, in 1996 and 2015, a supplementary nationally representative sample of individuals aged 50–56 years was collected using the sampling method applied in the baseline survey [27]. Detailed information about the study design and sampling of TLSA has been presented in the published research articles [28, 29]. The fourth wave of TLSA conducted in 1999 contained data on diet, nutrition, and life satisfaction index (LSI), which were consistent with the objectives of our study. Therefore, we set the 1999 data as a baseline and created categorical variables to differentiate the data using data from 2003, 2007, 2011, and 2015 to analyze the association between PA and F&V intake and LS over 16 years. After excluding the number of missing and deceased during the follow-up period, respondents who completed five waves of interviews and self-reports were included in the analysis. The number of respondents in each wave was: 4,440 (1999), 3,930 (2003), 3,215 (2007), 2,501 (2011), and 1,824 (2015). Exclusion is lost-to-follow-up mainly due to moving and rejection to be interviewed; missing is incomplete data on significant variables (Fig. 1).

Outcome measure

Life satisfaction (LS) was measured using the Life Satisfaction Index (LSI) [30], which comprises ten items [31] with higher scores indicating higher LS levels. The ten items are: (1) Is your life better than most people's? (2) Are you satisfied with your life? (3) Are you interested in what you do? (4) Have the last few years been the best in your life? (5) If possible, would you want to take another path and start your life over again? (6) Do you expect something happy to happen in the future? (7) Do you think your life should be better than it is now? (8) Do you feel that most of what you do is monotonous and of no interest? (9) Do you feel that you are old and that life is boring? (10) Would you say your life has matched your expectations? as "yes" or "no"? The items were reverse-scored when necessary and summed; accordingly, higher LSI scores correspond with higher LS (Cronbach's α = 0.73–0.81) [31]. The LSI has a score range of 0 to 10; a total score ≥ 6 was considered as feeling satisfied with life and a higher level of LS [31].

Independent variables

Physical activity (PA) was analyzed as an independent variable. We measured PA by considering the frequency, duration, and intensity of daily physical activity following the methodology of Haase et al. and Pitsavos et al. [32, 33]. Data regarding physical activity were generated from three questions in the questionnaire:

-

1.

"How often do you do routine physical exercise?" and the responses were (a) none (inactive, scored 0), (b) < 2 times/week (scored 1), (c) 3–5 times/week (scored 2) and (d) ≥ 6 times/week (scored 3).

-

2.

If you do physical exercise, "How many minutes do you spend each time?" and the responses were (a) < 15 min/time (scored 1), (b) 15–30 min/time (scored 2), and (c) ≥ 30 min/time (scored 3).

-

3.

"Do you sweat or pant after doing exercise?" and the responses were (a) no sweating or panting (scored 1) and (b) some or lots of sweating or panting (scored 2).

Each participant's total PA score was obtained by multiplying the scores of the three questions, and the total score ranged from 0 for inactive people to 18 for highly active people. Next, we calculated the total PA scores and classified them into three groups: low (inactive, total score = 0), moderate (generally active, total score = 1–7), and high (vigorous, total score = 8–18). The methods used in this study were similar to those used in previous relevant studies and were considered acceptable reliability [32,33,34].

A validated semiquantitative questionnaire was applied to assess the frequency of F&V intake, which in the present study was categorized as follows: "did not eat" as 0 times, < 1 time per week as 0.5 times, 1–2 times per week as 1.5 times, 3–5 times per week as 4 times, and eating every day as ≥ 6 times a week. The scores for the respective weekly intake of F&V were summed and classified into three groups: low (< 0–6 times), moderate (7–9 times), and high (≥ 10 times).

The combination of PA and F&V intake was classified into five groups: both-low (low PA and low F&V intake), both-high (high PA and high F&V intake), only-high-PA (high PA and low or moderate F&V intake), only-high-F&V intake (high F&V intake and low or moderate PA), and others (low PA and /or moderate F&V intake). Previous publications adopted these selected criteria [21, 22].

Covariates

Within our generalized estimating equations (GEEs) models, certain covariates such as age and education were treated as time-fixed variables, set at the baseline. Other covariates, such as health statuses and behaviors, were treated as time-varying, allowing them to change over the different waves of the study. Variables included possible related factors of LS: Age divided into three groups of 53–64, 65–74, and > 75; Education adjustment scores were applied for the following groups: ≤ 6, 712, and ≥ 13 years of formal education. Marital status was classified into two categories: yes or no. Regarding marital status, a ‘yes’ was assigned to participants currently married or in a marriage-like relationship, while ‘no’was assigned to participants who were divorced, widowed, separated, or never married. Participants responded yes/no about drinking alcohol: never drink once or twice a week. Participants were classified as nonsmokers or current/past smokers. Tea consumption was classified as < 3 times or ≥ 3 times a week. Hypertension, heart disease, and diabetes were classified based on diagnoses by a physician. Additionally, evidence regarding cardiovascular disease-related diseases was gathered. If the respondent reported having a doctor's diagnosis of heart disease, coronary heart disease, any other heart diseases, stroke, diabetes, or cancer; they were coded as having a history of such diseases.

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 22.0. We conducted an analysis using generalized estimating equations (GEEs) with adjustment of time-constant and time-varying covariates [35]. The net influence of PA and F&V intake on LS was examined with the adjustment of covariates. All analyses simultaneously assessed data from five waves of follow-up interviews in 1999 (baseline), 2003, 2007, 2011, and 2015. Data gathered throughout the 16-year study period were assessed simultaneously in all analyses. The baseline measures of LS were included to reduce unobserved heterogeneity. In addition, we took longitudinal models, including LS measurements from previous waves, to examine PA and F&V intake and their associations with LS. All values have been adjusted for weighting according to the study design. In this study, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the participants collected in 1999 regarding PA, F&V intake, and LS. A broader percentage of participants responded to the high PA (men 52.8%, women 45.6%) and F&V intake results (men 79.3%, women 83.7%). Results of the analysis of the combination of PA and F&V intake showed that the group with the highest percentage of males was both high (43.7%), and the group with the highest percentage of females was only F&V intake (39.1%). The results of the analysis of the Life Satisfaction Index (LSI) showed that 70.3% and 64.9% of the male and female participants, respectively, expressed satisfaction (LSI ≥ 6) with their lives.

Table 2 presents the characteristics of LSI collected from 1999 to 2015. According to the five survey waves data, men are more likely to be satisfied with their lives than women. However, both men and women gradually reduced their LS over time. The percentage of men who felt satisfied with their lives in 1999 was 70.3%, and in 2015 it was 63.8%.

The percentage of women who felt satisfied with their lives in 1999 was 64.9%, and in 2015 it was 57.5%. There was a significant difference in LS among the age groups (p < 0.01). Over the study period, the 53–64 years old group achieved an LS rate of 69.6%. Contrastingly, the ≧75 years old group showed the lowest LS rate in 2015 (44.4%), with an annual decrease Moreover, marital status, drinking, hypertension, and heart disease were significantly correlated with LS (Table 2).

For Figs. 2, analyses were conducted using specific models to assess the influence of sex and age on the relationship between PA, F&V intake, and LS. These models were adjusted for variables such as health status and behaviors. The adjustments aimed to control for potential confounders, providing a more accurate representation of the relationships. Figure 2 shows the gender differences between PA and F&V intake and the association at LS. As can be observed in Fig. 2a, there was a significant difference in PA for men in the only-high group (odds ratio [OR] = 1.48; 95% CI = 1·16–1·80) and for women in the moderate (OR = 1.67, 95% CI = 0.94–2.40) and high groups (OR = 1.85, 95% CI = 1.4–2.3). Figure 2b shows significant differences in the high-F&V group regardless of gender; the men’s OR was 1.41 (95% CI = 1.15–1.70), and the OR for women was 1.58 (95% CI = 1.20–2.05). Figure 2c also shows that combining PA and F&V had multiple significant differences in LS, and the combined both high group’s OR for men was 3.14 (95% CI = 1.8–4.5), and for women was 4.25 (95% CI = 2.1–6.8).

Figure 3 illustrates not only the combined effects of PA and F&V intake on LS but also presents a separate analysis to discern the individual influences of PA and F&V intake on LS across various ages. The three age groups showed significant differences in PA with LS. Only the 53–64 group with moderate PA did not show significant differences (Fig. 3a). The association was more significant in the 65–74 years-old group (OR = 2.02, 95% CI = 1.59–2.73) and ≧75 years-old group (OR = 1.61, 95% CI = 1.05–2.27) than in the 53–64 years-old group (OR = 1.41, 95% CI = 0.94–1.77). Similarly, F&V intake was positively correlated with LS (Fig. 3b). There were multiple significant differences, among which the 53–64 years-old group OR was 1.54;(95% CI = 1.10–2.05), and the 65–74 years-old group (OR = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.10–1.85) and ≧75 years-old groups (OR = 1.45, 95% CI = 1.22–2.78) in high-F&V intake. PA and F&V intake showed a significant combined association on LS except for the ≧75 years-old with an only-PA high group (Fig. 3c). The OR for 53–64 years-old group was 5.01 (95% CI = 2.50–9.50), the OR for 65–74 years-old group was 3.71 (95% CI = 2.22–6.50), and the OR for ≧75 years-old group was 2.58 (95% CI = 1.50–4.30). The result shows that combined PA and F&V intake can significantly promote LS, decreasing age-related association.

We performed GEE regression to analyze the correlation of PA and F&V intake on LS (Table 3). After adjusting for confounders, model 1 showed that moderate and high-PA levels significantly correlated LS (OR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.12–1.79 and OR = 1.74, 95% CI = 1.50–2.02). Moreover, high-F&V intake significantly correlated with LS (OR = 2.07, 95% CI = 1.69–2.53). Regarding the combined association shown in model 2 (Table 3), compared with the both-low-PA and F&V intake group, there were significantly higher LS levels in the both-high (OR = 4.69, 95% CI = 3.49–6.31), only-high-F&V intake (OR = 2.87, 95% CI = 2.14–3.85), only-high-PA (OR = 2.48, 95% CI = 1.74–3.52), and others groups (OR = 1.87, 95% CI = 1.33–2.64).

Discussion

Our findings demonstrated that PA and F&V intake showed a significant combined association with LS among older Taiwanese adults; moreover, PA and F&V intake each showed a significant positive correlation with LS. Our findings demonstrate the importance of PA and F&V intake in improving LS among older adults in Taiwan.

This study yielded meaningful evidence. First, this was a longitudinal national population-based cohort study on older Taiwanese adults. This is the first 16-year study on the association between PA and F&V intake among older adults in Asia. Second, we demonstrated the combined associations of PA and F&V intake on LS in Taiwanese older adults. Specifically, compared with the both-low PA and F&V intake group, the both-high PA and F&V intake, only-high F&V intake, and only-high PA groups showed a correlation of LS by 469%, 287%, and 248%, respectively. This suggests that concurrently practicing both habits yielded more health benefits than practicing each alone. However, the mechanisms underlying the positive relations of PA and F&V intake on LS remain unclear. The theoretical model of the impact of PA and F&V intake on life satisfaction can be established based on the relationship between quality of life and mental health. The following is a possible theoretical model—a model of how PA and F&V improve life satisfaction. Life satisfaction is a subjective evaluation of a person's quality of life. Quality of life includes factors such as physical, psychological, and social health, as well as meeting basic needs, personal growth, and social interaction [36, 37]. PA helps improve physical health, including enhancing cardiovascular health, maintaining a healthy weight, and enhancing muscle and bone strength. In addition, PA can also release endogenous hormones such as endorphins and dopamine, which can help improve mental health, reduce anxiety and depression, and increase happiness [38,39,40,41]. A balanced diet is crucial for maintaining physical health. F&V provides the nutrients the body needs, maintains endocrine balance, enhances immune system function, and prevents chronic diseases. At the same time, F&V intake also related to emotional and mental health, and certain foods can affect neurotransmitter levels, affecting emotions and mood [23, 42]. The impact of action between PA and F&V intake has a positive impact on mental health. Exercise promotes the release of endogenous hormones, enhances self-esteem and confidence, reduces stress, and increases the ability to resist depression and anxiety. A good diet helps stabilize blood sugar levels, reduce emotional fluctuations, and provide the body with the necessary nutrients to support nervous system function [38, 39]. By improving physical and mental health, PA and F&V intake can help improve the quality of life. When individuals feel good physical health, emotional stability, and social satisfaction, they are more likely to feel satisfied with life [40, 41]. Individual differences, cultural differences, social support, and other factors may also affect the impact of PA and F&V intake on life satisfaction. Different people may have different reactions to varying degrees of PA and F&V intake [24, 43]. This model emphasizes the positive impact of PA and F&V intake on life satisfaction, achieved by improving multiple aspects of quality of life. It emphasizes the interactive relationship between physical and mental health, as well as the role of PA and F&V intake in maintaining these health aspects. However, it should be noted that the actual results may vary depending on individual differences and environmental factors. Therefore, it is crucial to develop exercise and dietary plans tailored to the specific circumstances of different individuals to improve life satisfaction. This study has several limitations. First, some of the data were self-reported measures but showed acceptable validity and accuracy. The reliability of the questionnaire interview for assessing food intake is limited; however, it was administered to participants with memory loss. Second, quantitative assessment of food intake is challenging, especially among the older adults; accordingly, we analyzed the intake frequency rather than the quantity (serving size). Third, no reciprocal relationship of the study variables is assumed since the data are limited for performing multi-wave analysis of a panel model. From Fredrickson's broaden–and–build theoretical point of view [44], it is very well possible that feeling better also increases people's activities. Reciprocal causality requires the reconceptualization of the study variables in a panel data study, as noted by Leszczensky & Wolbring [45]. Fourth, due to the limited data, we did not consider the associations of significant SES (such as household income), life events (such as the loss of a partner), and external health system factors (such as policy and economics) on LS. Finally, there also have other residual confounding factors– for examples, there were any neighborhood-level factors that could have considered to adjust for in the analysis (e.g., access to public/private PA facilities, proximity to grocery stores, etc.). Also, other mental health variables (such as anxiety or depression) could have included in the analysis. Future studies should consider personal behaviors and their interplay in LS pathway mediation as antecedents of significant life events. In addition, researchers could facilitate a more in-depth understanding of variations in heart disease risk across different age ranges and may reveal additional correlations and causal relationships by using the autoregressive latent growth curve model [46].

Conclusion

Our findings confirmed that PA and F&V intake had a significant combined effect on LS among older Taiwanese individuals. These personal actions are safe, effective, and economical ways to associate life satisfaction and promote healthy, safe, and active aging. A standardized and specific program and policy are necessary to promote healthy habits in different older adults, such as daily PA and F&V intake, and one without the other, to improve longevity and healthy aging.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are not publicity available but are available from the https://www.hpa.gov.tw/EngPages/Detail.aspx?nodeid=1077&pid=6197 on request with the permission.

References

World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health. Geneva; 2015. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565042 Accessed April 30 2023.

World Health Organization. Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020; 2013. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506021 Accessed 30 April 2023.

Saxena S, Funk MK, Chisholm D. Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2020. East Mediterr Health J. 2015;21:461–3.

Steptoe A. Happiness and Health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:339–59. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044150.

Diener E, Oishi S, Lucas RE. Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annu Rev Psychol. 2003;54:403–25. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145056.

Zhu C, Lian Z, Huang Y, Zhong Q, Wang J. Association between subjective well-being and all-cause mortality among older adults in China. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):624. Published 2023 Aug 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05079-y

Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: does happiness lead to success? Psychol Bull. 2005;131(6):803–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803.

Pressman SD, Cohen S. Does positive affect influence health? Psychol Bull. 2005;131(6):925–71.

Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: a quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(7):741–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818105ba.

Okun MA, Stock WA. The construct validity of subjective well-being measures: an assessment via quantitative research syntheses. J Community Psychol. 1987;15(4):481–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(198710)15:4<481::AID-JCOP2290150406>3.0.CO;2-E.

Schimmack U, Oishi S. The influence of chronically and temporarily accessible information on life satisfaction judgments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;89(3):395–406.

Ostir GV, Markides KS, Black SA, Goodwin JS. Emotional well-being predicts subsequent functional independence and survival. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5):473–8.

Ng ST, Tey NP, Asadullah MN. What matters for life satisfaction among the oldest-old? Evidence from China. PLoS One. 2017;12.

Sampaio PY, Ito E. Activities with higher influence on quality of life in older adults in Japan. Occup Ther Int. 2013;20:1–10.

Cunningham C, O’Sullivan R, Caserotti P, Tully MA. Consequences of physical inactivity in older adults: A systematic review of reviews and meta-analyses. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2020;30(5):816–27.

U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. https://health.gov/our-work/nutrition-physical-activity/physical-activity-guidelines Accessed 30 April 2023.

Steptoe A, Perkins-Porras L, Hilton S, Rink E, Cappuccio FP. Quality of life and self-rated health in relation to changes in fruit and vegetable intake and in plasma vitamins C and E in a randomised trial of behavioural and nutritional education counselling. Br J Nutr. 2004;92:177–84.

Mujcic R, J Oswald A. Evolution of well-being and happiness after increases in consumption of fruit and vegetables. Am J Public Health. 2016; 106:1504–151.

Cheng HY, Shi YX, Yu FN, Zhao HZ, Zhang JH, Song M. Association between vegetables and fruits consumption and depressive symptoms in a middle-aged Chinese population: an observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019; 98: e15374.

Gehlich KH, Beller J, Lange-Asschenfeldt B, Köcher W, Meinke MC, Lademann J. Consumption of fruits and vegetables: improved physical health, mental health, physical functioning and cognitive health in older adults from 11 European countries. Aging Ment Health. 2020;24:634–41.

Li-Yun F, et al. The synergetic impact of physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption on the risk of depression in Taiwanese adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:7300.

Wang RS, Wang BL, Huang YN, Wan TTH. The combined effect of physical activity and fruit and vegetable intake on decreasing cognitive decline in older Taiwanese adults. Sci Rep. 2022;12:9825.

Brookie KL, Best GI, Conner TS. Intake of raw fruits and vegetables is associated with better mental health than intake of processed fruits and vegetables. Front Psychol. 2018;9:487.

Oldewage-Theron WH, Kruger R. Food variety and dietary diversity as indicators of the dietary adequacy and health status of an elderly population in Sharpeville. South Africa J Nutr Elder. 2008;27(1–2):101–33.

Liu LJ, Guo Q. Life satisfaction in a sample of empty-nest older adults: a survey in the rural area of a mountainous county in China. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:823–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-008-9370-1.

National Health Administration of the Ministry of Health and Welfare: Introduction to a series of long-term follow-up surveys on physical and mental and social living conditions of middle-aged and older adults. 2014; http://www.hpa.gov.tw/Bhpnet/web/HealthTopic/Topic.aspx?id=200712270002 Accessed April 20 2023.

Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare. Taiwan Longitudinal Study on Aging; 2015. https://www.hpa.gov.tw/1077/6197/e Accessed 21 April 2023.

Tsai AC, Chi SH, Wang JY. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations of lifestyle factors with depressive symptoms in ≥ 53-year old Taiwanese - results of an 8-year cohort study. Prev Med. 2013;57(2):92–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.04.021.

Zimmer Z, Martin LG, Chang MC. Changes in functional limitation and survival among older Taiwanese, 1993, 1996, and 1999. Popul Stud (Camb). 2002;56(3):265–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324720215931.

Neugarten BL, Havighurst RJ, Tobin SS. The measurement of life satisfaction. J Gerontol. 1961;16:134–43.

Hsu HC. Trajectories and covariates of life satisfaction among older adults in Taiwan. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55:210–6.

Haase A, Steptoe A, Sallis JF, Wardle J. Leisure-time physical activity in university students from 23 countries: associations with health beliefs, risk awareness, and national economic development. Prev Med. 2004;39:182–90.

Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos DB, Lentzas Y, Stefanadis C. Epidemiology of leisure-time physical activity in socio-demographic, lifestyle and psychological characteristics of men and women in greece: Te attica study. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:37.

Steptoe A, Wardle J, Cui W, et al. Trends in smoking, diet, physical exercise, and attitudes toward health in European university students from 13 countries, 1990–2000. Prev Med. 2002;35:97–104.

Liang KY, Zeger SL. Regression analysis for correlated data. Annu Rev Public Health. 1993;14:43–68.

Morawin B, Tylutka A, Chmielowiec J, Zembron-Lacny A. Circulating mediators of apoptosis and inflammation in aging; physical exercise intervention. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(6):3165.

Cadore EL, Izquierdo M. How to simultaneously optimize muscle strength, power, functional capacity, and cardiovascular gains in the elderly: an update. Age (Dordr). 2013;35:2329–44.

Klil-Drori S, Klil-Drori AJ, Pira S, Rej S. Exercise intervention for late-life depression: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020; 81(1):19r12877.

White RL, Babic MJ, Parker PD, Lubans DR, Astell-Burt T. Domain-specific physical activity and mental health: a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(5):653–66.

Netz Y, Wu MJ, Becker BJ, Tenenbaum G. Physical activity and psychological well-being in advanced age: a meta-analysis of intervention studies. Psychol Aging. 2005;20(2):272–84.

Siefken K, Junge A, Laemmle L. How does sport affect mental health? An investigation into the relationship of leisure–time physical activity with depression and anxiety. Hum Mov. 2019;20(1):62–74.

Godoy-Izquierdo D, Ogallar A, Lara R, Rodríguez-Tadeo A, Arbinaga F. Association of a mediterranean diet and fruit and vegetable consumption with subjective well-being among adults with overweight and obesity. Nutrients. 2021;13(4):1342.

Huang YC, Wahlqvist ML, Lee MS. Appetite predicts mortality in free-living older adults in association with dietary diversity. A NAHSIT cohort study. Appetite. 2014; 83,89–96.

Fredrickson BL. The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philos Trans Royal Soc London B Biol Sci. 2004; 359(1449):1367–1377.

Leszczensky L, Wolbring T. How to deal with reverse causality using panel data? Recommendations for researchers based on a simulation study. Sociol Methods Res. 2022;51(2):837–65.

Wan TT. Evidence-based health care management: Multivariate modeling approaches. Springer Science & Business Media; 2002

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the CAMS & PUMC, China (Grant number: 2021-RC630-001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.S.W. and B.L.W. designed the study; R.S.W. and B.L.W. drafted the manuscript; B.L.W., M.L W., T.T.H.W. and T.H.T. directed the study and reviewed the manuscript; R.S.W., B.L.W. and Y.N.H. directed statistical analysis and helped interpret the results. M.L W., T.T.H.W. and T.H.T. edited the paper and suggested the future direction for further investigation, all authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent. We confirmed that all methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center (approval number: TSGHIRB: B-109–30).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, R.S., Huang, YN., Wahlqvist, M.L. et al. The combination of physical activity with fruit and vegetable intake associated with life satisfaction among middle-aged and older adults: a 16-year population-based cohort study. BMC Geriatr 24, 41 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04563-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04563-0