Abstract

It is often thought that an external threat increases the internal cohesion of a nation, and thus decreases polarization. We examine this proposition by analyzing NATO discussion dynamics on Finnish social media following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. In Finland, public opinion on joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) had long been polarized along the left-right partisan axis, but the invasion led to a rapid convergence of opinion toward joining NATO. We investigate whether and how this depolarization took place among polarized actors on Finnish Twitter. By analyzing retweet patterns, we find three separate user groups before the invasion: a pro-NATO, a left-wing anti-NATO, and a conspiracy-charged anti-NATO group. After the invasion, the left-wing anti-NATO group members broke out of their retweeting bubble and connected with the pro-NATO group despite their difference in partisanship, while the conspiracy-charged anti-NATO group mostly remained a separate cluster. Our content analysis reveals that the left-wing anti-NATO group and the pro-NATO group were bridged by a shared condemnation of Russia’s actions and shared democratic norms, while the other anti-NATO group, mainly built around conspiracy theories and disinformation, consistently demonstrated a clear anti-NATO attitude. We show that an external threat can bridge partisan divides in issues linked to the threat, but bubbles upheld by conspiracy theories and disinformation may persist even under dramatic external threats.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Despite a period of momentum building, the Russian invasion of Ukraine on Feb 24, 2022 came as a shock to most observers. The shock was most acute in Ukraine but was felt also in countries bordering Russia. Finland, the militarily non-aligned European country that shares a 1344-kilometer border with Russia, witnessed a sharp shift in its public opinion on NATO membership, based on a reappraisal of the external threat posed by Russia. Traditionally, around 20 percent of the Finnish population had been in favor of joining NATO [1]. Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014 increased the number to 25–30 [1], but after the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, support for joining NATO soared as high as 70–80 percent [2].

Behind this major change in opinion, the rising external threat seems to have had a depolarizing effect on the Finnish NATO discussion. For long, Finnish opinions on NATO embodied a polarization that was largely partisanship-based: voters of the main right-wing party (National Coalition) were largely in favor of joining, whereas voters of left-wing parties were the most vocal opponents of NATO [3]. After the invasion, however, many left-wing supporters changed their opinion, and eventually the Finnish parliament almost unanimously voted in favor of joining NATO (188 for, 8 against).

Social media opens an unobtrusive observation window [4] into whether and how this depolarization took place among the more politically active and partisan segment of the population [5, 6], including political elites who often play an important role in steering the discussion [7, 8], as well as fringe communities that subscribe to conspiracy theories and disinformation [34] and diffusion networks [33]. Bessi et al. [35] showed that conspiracy news consumers are more focused on diffusing within-group content and interacting with within-group actors, which points to the potential stability of conspiracy-based polarization. Zollo et al. [50] further added that users within the conspiracy echo chamber rarely interact with debunking posts, and when they do, their interest in conspiracy content actually increases after the interaction. Echoing these findings, our results more concretely demonstrate the resilience of conspiracy-/disinformation-based polarization. We show that consumers of conspiracy theories and disinformation formed a separate retweeting bubble, and further, that they were reluctant to change their opinions or communication patterns even in the face of a dramatic external threat and otherwise bridged partisan divides. This alerts us to the fact that conspiracy theories and disinformation are consumed by polarized actors that are even more entrenched than partisan actors, and that it can be extremely difficult to pave a way toward conversation and consensus with them.

Data availability

The code, tweet IDs, and anonymized retweet networks for generating the results described in the paper are available at https://github.com/ECANET-research/finnish-nato.

Abbreviations

- NATO:

-

North Atlantic Treaty Organization

- API:

-

Application Programming Interface

- E/I ratio:

-

external-internal ratio

References

Haavisto I (2022) At nato’s door. EVA Analysis (104)

Yle (2022) Yle poll: support for NATO membership soars to 76%. https://yle.fi/a/3-12437506. Accessed 12 April 2023

Forsberg T (2018) Finland and NATO: strategic choices and identity conceptions. In: The European neutrals and NATO: non-alignment, partnership, membership? pp 97–127

Barberá P, Steinert-Threlkeld ZC (2020) How to use social media data for political science research. In: The SAGE handbook of research methods in political science and international relations, vol 2, pp 404–423

Ruoho I, Kuusipalo J (2019) The inner circle of power on Twitter? How politicians and journalists form a virtual network elite in Finland. Observatorio 13(1):70–85. https://doi.org/10.15847/obsobs13120191326

Bail C (2021) Breaking the social media prism: how to make our platforms less polarizing. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Matsubayashi T (2013) Do politicians shape public opinion? Br J Polit Sci 43(2):451–478

Barberá P, Zeitzoff T (2018) The new public address system: why do world leaders adopt social media? Int Stud Q 62(1):121–130

Suresh VP, Nogara G, Cardoso F, Cresci S, Giordano S, Luceri L (2023) Tracking fringe and coordinated activity on Twitter leading up to the US Capitol attack. ar**v preprint. ar**v:2302.04450

Sharma K, Ferrara E, Liu Y (2022) Characterizing online engagement with disinformation and conspiracies in the 2020 US presidential election. In: Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media, vol 16, pp 908–919

Erokhin D, Yosipof A, Komendantova N (2022) Covid-19 conspiracy theories discussion on Twitter. Soc Media Soc 8(4):20563051221126051

Conover M, Ratkiewicz J, Francisco M, Gonçalves B, Menczer F, Flammini A (2011) Political polarization on Twitter. In: Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media, vol 5, pp 89–96

Barberá P, Jost JT, Nagler J, Tucker JA, Bonneau R (2015) Tweeting from left to right: is online political communication more than an echo chamber? Psychol Sci 26(10):1531–1542

Garimella K, Morales GDF, Gionis A, Mathioudakis M (2018) Quantifying controversy on social media. ACM Trans Soc Comput 1(1):1–27

Cossard A, Morales GDF, Kalimeri K, Mejova Y, Paolotti D, Starnini M (2020) Falling into the echo chamber: the Italian vaccination debate on Twitter. In: Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media, vol 14, pp 130–140

Morales AJ, Borondo J, Losada JC, Benito RM (2015) Measuring political polarization: Twitter shows the two sides of Venezuela. Chaos, Interdiscip J Nonlinear Sci 25(3):033114

Esteve Del Valle M, Broersma M, Ponsioen A (2022) Political interaction beyond party lines: communication ties and party polarization in parliamentary Twitter networks. Soc Sci Comput Rev 40(3):736–755

Chen THY, Salloum A, Gronow A, Ylä-Anttila T, Kivelä M (2021) Polarization of climate politics results from partisan sorting: evidence from Finnish twittersphere. Glob Environ Change 71:102348

Weber I, Garimella VRK, Batayneh A (2013) Secular vs. Islamist polarization in Egypt on Twitter. In: Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/ACM international conference on advances in social networks analysis and mining, pp 290–297

Borge-Holthoefer J, Magdy W, Darwish K, Weber I (2015) Content and network dynamics behind Egyptian political polarization on Twitter. In: Proceedings of the 18th ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work & social computing, pp 700–711

Garcia MB, Cunanan-Yabut A (2022) Public sentiment and emotion analyses of Twitter data on the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. In: 2022 9th international conference on information technology, computer, and electrical engineering (ICITACEE). IEEE, New York, pp 242–247

Mir AA, Rathinam S, Gul S, Bhat SA (2023) Exploring the perceived opinion of social media users about the Ukraine–Russia conflict through the naturalistic observation of tweets. Soc Netw Anal Min 13(1):44

Evkoski B, Kralj Novak P, Ljubešić N (2023) Content-based comparison of communities in social networks: ex-Yugoslavian reactions to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Appl Netw Sci 8(1):1–24

Caprolu M, Sadighian A, Di Pietro R (2023) Characterizing the 2022-Russo-Ukrainian conflict through the lenses of aspect-based sentiment analysis: dataset, methodology, and key findings. In: 2023 32nd international conference on computer communications and networks (ICCCN). IEEE, New York, pp 1–10

Ibar-Alonso R, Quiroga-García R, Arenas-Parra M (2022) Opinion mining of green energy sentiment: a Russia-Ukraine conflict analysis. Mathematics 10(14):2532

Geissler D, Bär D, Pröllochs N, Feuerriegel S (2023) Russian propaganda on social media during the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. EPJ Data Sci 12(1):35

Pierri F, Luceri L, **dal N, Ferrara E (2023) Propaganda and misinformation on Facebook and Twitter during the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In: Proceedings of the 15th ACM web science conference 2023, pp 65–74

Nisch S (2023) Public opinion about Finland joining nato: analysing Twitter posts by performing natural language processing. J Contemp Eur Stud. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2023.2235565

Myrick R (2021) Do external threats unite or divide? Security crises, rivalries, and polarization in American foreign policy. Int Organ 75(4):921–958

Bessi A, Ferrara E (2016) Social bots distort the 2016 US presidential election online discussion. First Monday 21(11-7)

Coser LA (1956) The functions of social conflict, vol 9. Routledge, Abingdon

Chowanietz C (2011) Rallying around the flag or railing against the government? Political parties’ reactions to terrorist acts. Party Polit 17(5):673–698

Del Vicario M, Bessi A, Zollo F, Petroni F, Scala A, Caldarelli G, Stanley HE, Quattrociocchi W (2016) The spreading of misinformation online. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113(3):554–559

Bessi A, Petroni F, Vicario MD, Zollo F, Anagnostopoulos A, Scala A, Caldarelli G, Quattrociocchi W (2016) Homophily and polarization in the age of misinformation. Eur Phys J Spec Top 225:2047–2059

Bessi A, Coletto M, Davidescu GA, Scala A, Caldarelli G, Quattrociocchi W (2015) Science vs conspiracy: collective narratives in the age of misinformation. PLoS ONE 10(2):0118093

Twitter (2022) Twitter API documentation | Docs | Twitter Developer Platform. https://developer.twitter.com/en/docs/twitter-api. Accessed 12 April 2023

Metaxas P, Mustafaraj E, Wong K, Zeng L, O’Keefe M, Finn S (2015) What do retweets indicate? Results from user survey and meta-review of research. In: Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media, vol 9, pp 658–661

Traag VA, Waltman L, Van Eck NJ (2019) From Louvain to Leiden: guaranteeing well-connected communities. Sci Rep 9(1):1–12

Peixoto TP (2018) Nonparametric weighted stochastic block models. Phys Rev E 97(1):012306

Hayes AF, Krippendorff K (2007) Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Commun Methods Meas 1(1):77–89

**a Y, Gronow A, Kukkonen A, Chen THY, Kivelä M et al (2021) Botit ja informaatiovaikuttaminen twitterissä vuoden 2021 kuntavaaleissa-elebot-2021-hanke

Salloum A, Takko T, Peuhkuri M, Kantola R, Kivelä M et al (2019) Botit ja informaatiovaikuttaminen twitterissä suomen eduskunta-ja eu-vaaleissa 2019-elebot-hanke

Hu Y (2005) Efficient, high-quality force-directed graph drawing. Math J 10(1):37–71

Seuri V (2019) Nyt tutkimaan: Ylen eduskuntavaalien vaalikoneen aineisto julkaistu avoimena datana [Let’s analyse: YLE election assistant tool data released as open access]. https://yle.fi/a/3-10725384. Accessed 26 October 2023

Salloum A, Chen THY, Kivelä M (2022) Separating polarization from noise: comparison and normalization of structural polarization measures. In: Proceedings of the ACM on human-computer interaction 6 (CSCW1), pp 1–33

Hanley HW, Kumar D, Durumeric Z (2023) Happenstance: utilizing semantic search to track Russian state media narratives about the Russo-Ukrainian war on Reddit. In: Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media, vol 17, pp 327–338

Noelle-Neumann E (1974) The spiral of silence a theory of public opinion. J Commun 24(2):43–51

Brody RA, Shapiro CR (1989) Policy failure and public support: the Iran-contra affair and public assessment of president Reagan. Polit Behav 11(4):353–369

Mutz DC (2002) Cross-cutting social networks: testing democratic theory in practice. Am Polit Sci Rev 96(1):111–126

Zollo F, Bessi A, Del Vicario M, Scala A, Caldarelli G, Shekhtman L, Havlin S, Quattrociocchi W (2017) Debunking in a world of tribes. PLoS ONE 12(7):0181821

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Ted Hsuan Yun Chen, Risto Kunelius, and the anonymous reviewers for giving extremely insightful feedback on our study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland (320780, 320781, 332916, 349366, 352561), the Kone Foundation (201804137), and the Helsingin Sanomat Foundation (20210021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YX, AG, AM, TY, BK, and MK designed research, performed research, and analyzed data; YX, AG, AM, TY, and MK wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 A.1 Data collection keywords

Two of the authors who are experts on Finnish politics developed a list of keywords related to the Finnish NATO discussion. We here present the original keywords in Finnish along with their rough translations into English (many of the words are context specific): liittoutua (to ally), liittoutumaton (non-aligned), liittoutumattomana (as non-aligned), liittoutumattomuuden (non-alignment), liittoutumattomuus (non-alignment), liittoutuminen (allying), liittoutumisen (allying), nato (NATO), nato-kumppani (NATO partner), nato-kumppanien (NATO partners’), nato-kumppanit (NATO partners), nato-kumppanuus (NATO partnership), nato-yhteistyö (NATO cooperation), nato-yhteistyön (of NATO cooperation), nato-yhteistyössä (in NATO cooperation), nato-yhteistyötä (NATO cooperation), naton (of NATO), natoon (into NATO), natossa (in NATO), natosta (from NATO), puolustusliiton (defense alliance’s), puolustusliitosta (from the defense alliance), puolustusliitto (defense alliance), puolustusliittoon (into the defense alliance), sotilasliiton (military alliance’s), sotilasliitosta (from the military alliance), sotilasliitto (military alliance), sotilasliittoon (into the military alliance), suominatoon (Finland into NATO), natojäsenyyttä (NATO membership), natojäsenyyden (NATO membership’s), nato-trolli (NATO troll), nato-trollit (NATO trolls), nato-trollien (NATO trolls’), nato-trollaajat (NATO troll users), nato-trollaajien (NATO troll users’), nato-kiima (NATO heat), nato-kiiman (NATO heat’s), nato-kiimailijat (NATO enthusiasts), nato-kiimailijoiden (NATO enthusiasts’), natoteatteri (NATO theater), natoteatteria (NATO theater), and natoteatterista (from the NATO theater).

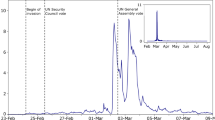

1.2 A.2 Tweet sampling statistics

For each group and each period, we sampled 42 tweets from those that got retweeted at least once in the group in the period. In total, 1800/221/416 tweets in the before period, 4188/343/1118 tweets in the right-after period, 2698/257/779 tweets in the 1-week-after period, and 1022/88/481 tweets in the 4-weeks-after period got retweeted at least once in respectively the pro, left-anti, and conspiracy-anti group.

1.3 A.3 Extra retweet network plots

Retweet networks in the 1-week-after and 4-weeks-after periods are plotted in Fig. 2.

Retweet networks 1 week after and 4 weeks after the invasion. Retweet network (A) 1 week after and (B) 4 weeks after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Networks are drawn using the SFDP spring-block layout [43]. Node colors correspond to the three groups detected in the before network, and the statistics beside each network show the number of users, the number of external retweets of the pro group, the number of internal retweets, and the E/I ratio in each anti group

1.4 A.4 Statistical test of network structure change

Due to the varying user group size in the retweet networks across different time periods, the observed change in E/I ratio can potentially be explained by statistical fluctuations. Here, we conduct a statistical test to see if the observed E/I ratio change after the invasion is higher in the left-anti group than in the conspiracy-anti group despite statistical fluctuations.

We suppose the retweets by each anti group are generated by a hypothetical model where each retweet is an external retweet of the pro group with probability \(p_{E}\), or an internal retweet with probability \(1-p_{E}\). We assume the uniform \(\operatorname{Beta}(1,1)\) prior on \(p_{E}\), which leads to the posterior distribution of \(p_{E}\sim \operatorname{Beta}(1+n_{E},1+n_{I})\), where \(n_{E}\) is the observed number of external retweets, and \(n_{I}\) is the observed number of internal retweets in a certain period. For respectively the before period and the right-after period, we calculate the posterior distribution of \(p_{E}\) in respectively the left-anti group and the conspiracy-anti group. For example in the left-anti group, \(p_{E}\sim \operatorname{Beta}(1+41,1+468)\) in the before period, and \(p_{E}\sim \operatorname{Beta}(1+166,1+193)\) in the right-after period; in the conspiracy-anti group, \(p_{E}\sim \operatorname{Beta}(1+96,1+1216)\) in the before period, and \(p_{E}\sim \operatorname{Beta}(1+389,1+1946)\) in the right-after period.

We run 100,000 rounds of simulations. In each round, for respectively the before period and the right-after period, we sample \(\hat{p}_{E}^{L}\) from the posterior distribution of \(p_{E}\) in the left-anti group, and \(\hat{p}_{E}^{C}\) from the posterior distribution of \(p_{E}\) in the conspiracy-anti group. We then numerically calculate the expected E/I ratio in the left-anti group \(R^{L}\) (resp. in the conspiracy-anti group \(R^{C}\)) based on the sampled \(\hat{p}_{E}^{L}\) (resp. \(\hat{p}_{E}^{C}\)). Then we obtain the E/I ratio change induced by the invasion in the left-anti group \(Q_{R}^{L}=R_{\mathrm{after}}^{L}/R_{\mathrm{before}}^{L}\) (resp. in the conspiracy-anti group \(Q_{R}^{C}=R_{\mathrm{after}}^{C}/R_{\mathrm{before}}^{C}\)). Finally, we obtain distributions of \(Q_{R}^{L}\) and \(Q_{R}^{C}\) over 100,000 simulations. We conduct a similar analysis also for the E/I ratio change in the 1-week-after period (as compared with the before period) and in the 4-weeks-after period (as compared with the before period).

As shown in Fig. 3 and Table 2, there is a certain range of variance in E/I ratio change that can be explained by statistical fluctuations, and the variance increases in later periods as the group size decreases. However, despite statistical fluctuations, the E/I ratio change induced by the invasion is still consistently higher in the left-anti group than in the conspiracy-anti group.

1.5 A.5 Tweets with unclear stance

In our tweet stance coding, a tweet is labeled “unclear” if it does not explicitly express a positive or negative attitude toward NATO. Thus, in general, the label “unclear” does not necessarily imply an ambiguous attitude toward NATO, but rather that the tweet does not clearly indicate any attitude. For example, tweets labeled “unclear” can be reactions to what was currently taking place in the Ukraine war (while NATO was also mentioned) or in the Finnish NATO policy process.

More specifically in the pro-NATO group, many tweets were labeled “pro” in the earlier periods because they were advocating for two citizen initiatives that were pro-NATO; but later on, these initiatives became irrelevant because the needed signatures were collected, and the NATO policy process moved on. Thus in later periods, many clearly pro-NATO tweets disappeared from the pro-NATO group and, for example, many tweets condemning Russia’s actions in Ukraine took their place. The latter are often labeled “unclear” as they are less clearly in favor of NATO, even though such a stance might be implicit. In general, the increase of tweets with unclear stance does not suggest that the group moved toward an ambiguous stance on NATO.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

**a, Y., Gronow, A., Malkamäki, A. et al. The Russian invasion of Ukraine selectively depolarized the Finnish NATO discussion on Twitter. EPJ Data Sci. 13, 1 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-023-00441-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-023-00441-2