Abstract

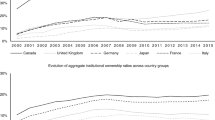

Investor time horizon varies by company, industry and economic system. In this article we explore the importance of this variation by studying the impact of shareholder time horizon on the investment decisions of the firms they own, and externalities on the wider market. We demonstrate theoretically that short-term shareholders cause Boards to care about the path of the stock price, rationalising firms’ pursuit of investments for signalling reasons at the expense of long-term value. We demonstrate that short-termism has spillover effects, leading to higher costs of equity capital; bubbles in the price of input assets; and predictable excess returns. We build testable cross-country hypotheses and evaluate these using existing evidence coupled with a new dataset on owner duration of US and Germanic firms.

Abstract

L’horizon temporel des investisseurs varie suivant les entreprises, le secteur d’activité et le système économique. Dans cet article, nous explorons l'importance de cette variation en étudiant l’impact de l’horizon temporel des actionnaires sur les décisions d’investissement des entreprises qu’ils possèdent, ainsi que les externalités sur un marché plus large. Nous démontrons, d’un point de vue théorique, que les actionnaires ayant une vision à court terme incitent les comités exécutifs à considérer l’évolution du prix de l’action, en rationalisant la poursuite des investissements pour des raisons de signalisation aux dépens de la valeur à long terme. Nous démontrons qu’une vision à court terme a des retombées qui entraînent des coûts plus élevés concernant les fonds propres; des bulles dans le prix des actifs entrants; et des rendements prévisionnels excessifs. Nous émettons des hypothèses qui peuvent être testées au niveau des pays et nous les évaluons en utilisant les preuves existantes combinées avec une nouvelle base de données portant sur la durée de propriété des entreprises américaines et germaniques.

Abstract

El horizonte del tiempo del inversionista varía según la empresa, la industria y el sistema económico. En este artículo exploramos la importancia de esta variación a través de estudiar el impacto del horizonte de tiempo de los agentes de interés en las decisiones de inversión de las empresas de su propiedad, y las externalidades del mercado ampliado. Teoréticamente demostramos que los agentes de interés de corto plazo causan que la Junta Directiva cuide la trayectoria del precio de las acciones, racionalizando la búsqueda de inversiones mediante indicar razones a costa del valor a largo plazo. Demostramos que el cortoplacismo tiene efectos indirectos , llevando a altos costos de capital patrimonial; burbujas en el precio de los activos; y exagerados retornos previsibles. Construimos una hipótesis probable entre países, y evaluamos estas usando la evidencia existencia paralelamente con una nueva base de datos de duración de propiedad de firmas Estadounidenses y Germánicas.

Abstract

O horizonte de tempo de um investidor varia de acordo com a empresa, a indústria e o sistema econômico. Neste artigo exploramos a importância dessa variação ao estudar o impacto do horizonte de tempo do acionista sobre as decisões de investimento das empresas de sua propriedade, e nas externalidades no mercado amplo. Nós demonstramos teoricamente que acionistas de curto prazo fazem o conselho se preocupar com a evolução do preço das ações, limitando a busca da empresa por investimentos a sinalizações, às custas do valor a longo prazo. Nós demonstramos que a visão de curto prazo tem efeitos colaterais, levando a maiores custos de capital próprio; bolhas no preço dos ativos de entrada; e retornos excessivos e previsíveis. Nós construímos hipóteses testáveis interpaíses e as avaliamos usando evidências existentes juntamente com um novo conjunto de dados sobre a duração do dono em empresas americanas e germânicas.

Abstract

投资者的投资期随公司、行业和经济系统而变。在这篇文章中, 我们通过研究股东投资期对他们所拥有公司的投资决策的影响, 探索了这一变化的重要性及更广泛的市场外部性。我们从理论上证明 : 短期股东引发董事会关心股票价格路径, 使公司以长远价值为代价的意在给出信号的投资追求合理化。我们证明短期主义有溢出效应, 导致更高的股权资本成本; 输入资产价格泡沫; 及可预测的超额回报。我们构建了可验证的跨国家的假设, 并使用现有证据加上新数据集在美国和日耳曼公司所有者持续期间评价这些假设。

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There are competing theories as to the reason behind the difference in the level of short-termism across countries, see for example Shao et al. (2013).

In the United Kingdom the Kay review also concluded that “short-termism is a problem” (Kay, 2012, Executive Summary, Para ii). They proposed, inter alia, that CEO remuneration should be altered to forcibly reduce the weighting on current performance. In the EU the European Commission are looking into increasing the voting weight of shareholders who are long-term holders of the stock. (See Brussels aims to reward investor loyalty, Financial Times, 23 January 2013.)

This asymmetric information assumption is not controversial. However this is not to say that management cannot learn anything from the market; Foucault and Laurent (2014).

The alternative to this assumption is that firms maximise the net present value (NPV) of future cash flows. DeAngelo (1981) argues that when asymmetric information exists (as in the model presented), this alternative paradigm would not apply.

We normalise the discount factor between the first and second periods to 1: This is without loss of generality for a risk-neutral Board. A time discount factor δ would alter anticipated t=2 payoffs to

: The analysis would be unchanged if one substituted

: The analysis would be unchanged if one substituted  for

for  .

.This liquidity shock assumption is standard in the banking literature, see Allen and Gale (2009).

For example, the Chairman of Cadbury, the main UK confectionery company until its purchase by Kraft, claimed to be very aware of the time horizon of his investors, and how it changed during the takeover process. See “The inside story of the Cadbury Takeover”. Financial Times, 12 March 2010.

Note that, in this model, firms that choose the business-as-usual technology are not affected by the distortions caused by the presence of short-term shareholders. This follows as the price of the input required for the low-risk technology is not altered by reductions in demand. If it were then the comparison between the two technology choices would be exacerbated, strengthening our results.

The

share price is not raised here by the absence of short-sellers (Lamont, 2012). Neither long nor short-term shareholders have privileged information at

share price is not raised here by the absence of short-sellers (Lamont, 2012). Neither long nor short-term shareholders have privileged information at  as to whether the firm is at the top or bottom end of the ability range with respect to the risky technology. The share price is the market’s expected value of the firm’s type conditional on all available public information.

as to whether the firm is at the top or bottom end of the ability range with respect to the risky technology. The share price is the market’s expected value of the firm’s type conditional on all available public information.See footnote 2 and the discussion that refers to it.

Formally we study the constant elasticity of supply function,

. The full analysis, as noted above, is given in Appendix B.

. The full analysis, as noted above, is given in Appendix B.Though a full welfare analysis is not possible, we are able to show that elasticity in the supply of the input asset has two opposing effects. The reduction in the price of the input due to more elastic supply leads to firms develo** the risky technology at greater volume, increasing output and in turn welfare. However, a more elastic supply leads to an increase in the misallocation of firms to the risky technology (Proposition 2), reducing long-run profits, and therefore welfare. The overall implications of elastic supply are therefore a priori ambiguous and likely depend upon the functional forms studied.

Botosan (1997) uses an accounting based approach; Gebhardt et al. (2001) use a residual income model.

The

stage would be when the success or failure of incorporating and running the acquired company becomes apparent.

stage would be when the success or failure of incorporating and running the acquired company becomes apparent.We focus on the tight [−1, +1] event window as returns to bidders over longer periods are likely affected by differences in takeover rules unrelated to short-termism in the economy.

In particular the short-term shareholders used in the empirical analysis of Gaspar et al. (2005) are professional investors and so their ability to monitor would likely be higher than for many passive owners; further, professional investors would have a strong incentive to not allow management to lower the value of their investment.

Gaspar et al. (2005) suggest that share prices can take many months to account for short-termism among owners.

Won in 2015 by Home Depot and Galaries Lafayette respectively.

Both won in 2014 by Victoria’s Secret.

For CDO market growth see Deutsche Bank (2007). For Citi’s prominent position in this market see “Merrill, Citigroup Record CDO Fees Earned in Top Growth Market”, Bloomberg, available at http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=a.FcDwf1.ZG4

Source: Table 5.2: 70, Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (2011).

Subprime interest rates dropped consistently after 2000, Figure 1 of Chomsisengphet and Pennington-Cross (2006).

To see this, note that at

the supply is b and the critical firm type is

the supply is b and the critical firm type is  given by (A8).

given by (A8).

References

Albagli, E., Hellwig, C., & Tsyvinski, A. 2011. A theory of asset prices based on heterogeneous information. Working Paper: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Allen, F., & Gale, D. 2000. Bubbles and crises. The Economic Journal, 110 (460): 236–255.

Allen, F., & Gale, D. 2009. Understanding Financial Crises: Clarendon Lectures in Finance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Allen, F., Morris, S., & Postlewaite, A. 1993. Finite bubbles with short sale constraints and asymmetric information. Journal of Economic Theory, 61 (2): 206–229.

Anderson, R. C., Duru, A., & Reeb, D. M. 2012. Investment policy in family controlled firms. Journal of Banking & Finance, 36 (6): 1744–1758.

Anderson, R. C., & Reeb, D. M. 2003. Founding-family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the P 500. Journal of Finance, 58 (3): 1301–1327.

Andrade, G., Mitchell, M., & Stafford, E. 2001. New evidence and perspectives on mergers. Journal of Eonomic Perspectives, 15 (2): 103–120.

Antia, M., Pantzalis, C., & Park, J. C. 2010. CEO decision horizon and firm performance: An empirical investigation. Journal of Corporate Finance, 16 (3): 288–301.

Aspen Institute. 2009. Overcoming short-termism: A call for a more responsible approach to investment and business management. Technical report, Aspen Institute, Business and Society Program.

Barber, B. M., & Lyon, J. D. 1997. Detecting long-run abnormal stock returns: The empirical power and specification of test statistics. Journal of Financial Economics, 43 (3): 341–372.

Bebchuk, L. A., Brav, A., & Jiang, W. 2015. The long-term effects of hedge fund activism. Columbia Law Review, 114 (5): 13–66.

Bebchuk, L. A., & Stole, L. A. 1993. Do short-term objectives lead to under- or overinvestment in long-term projects? Journal of Finance, 48 (2): 719–730.

Berle, A. A., & Means, G. C. 1933. The Modern Corporation and Private Property. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Black, A., & Fraser, P. 2002. Stock market short-termism – An international perspective. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 12 (2): 135–158.

Bolton, P., Scheinkman, J., & **ong, W. 2006. Executive compensation and shorttermist behaviour in speculative markets. Review of Economic Studies, 73 (3): 577–610.

Botosan, C. 1997. Disclosure level and the cost of equity capital. Accounting Review, 72 (3): 323–350.

Bühner, R. 1991. The success of mergers in Germany. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 9 (4): 513–532.

Campbell, T. S., & Marino, A. M. 1994. Myopic investment decisions and competitive labor markets. International Economic Review, 35 (4): 855–875.

Chomsisengphet, S., & Pennington-Cross, A. 2006. The evolution of the subprime mortgage market. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 88 (1): 31–56.

Claessens, S., Djankova, S., & Lang, L. H. 2000. The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 58 (1–2): 81–112.

DeAngelo, H. 1981. Competition and unanimity. American Economic Review, 71 (1): 18–27.

Derrien, F., Kecskés, A., & Thesmar, D. 2013. Investor horizons and corporate policies. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 48 (6): 1755–1780.

Deutsche Bank. 2007. Global CDO market: Overview and outlook – Global Securitisation and Structured Finance.

Faccio, M., & Lang, L. H. 2002. The ultimate ownership of Western European corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 65 (3): 365–395.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. 1997. Industry costs of equity. Journal of Financial Economics, 43 (2): 153–193.

Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. 2011. Financial crisis inquiry report. Technical report, US Government, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GPOFCIC/pdf/GPO-FCIC.pdf, accessed 26 August 2014.

Foucault, T., & Laurent, F. 2014. Learning from peers’ stock prices and corporate investment. Journal of Financial Economics, 111 (3): 554–577.

Gaspar, J.-M., Massa, M., & Matos, P. 2005. Shareholder investment horizons and the market for corporate control. Journal of Financial Economics, 76 (1): 135–165.

Gebhardt, W. R., Lee, C. M. C., & Swaminathan, B. 2001. Toward an implied cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 39 (1): 135–176.

Goergen, M., & Renneboog, L. 2004. Shareholder wealth effects of European domestic and cross-border takeover bids. European Financial Management, 10 (1): 9–45.

Graham, J., Harvey, C., & Rajgopal, S. 2005. The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 40 (1–3): 3–73.

Hillier, D., Pindado, J., de Queiroz, V., & de la Torre, C. 2011. The impact of country-level corporate governance on research and development. Journal of International Business Studies, 42 (1): 76–98.

Holderness, C. 2009. The myth of diffuse ownership in the united states. Review of Financial Studies, 22 (4): 1377–1408.

Jensen, M. C., & Ruback, R. S. 1983. The market for corporate control: The scientific evidence. Journal of Financial Economics, 11 (1–4): 5–50.

John, K., Litov, L., & Yeung, B. 2008. Corporate governance and risk taking. Journal of Finance, 63 (4): 1679–1728.

Kay, J. 2012. The Kay review of UK equity markets and long term decision making. Technical report, UK Department of Business, Innovation and Skills.

Kothari, S., & Warner, J. B. 1997. Measuring long-horizon security price performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 43 (3): 301–339.

Kumar, P., & Langberg, N. 2009. Corporate fraud and investment distortions in efficient capital markets. The RAND Journal of Economics, 40 (1): 144–172.

La Porta, R., de Silanes, F. L., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. 1998. Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106 (6): 1113–1155.

Lambert, R., Leuz, C., & Verrecchia, R. E. 2007. Accounting information, disclosure, and the cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 45 (2): 385–420.

Lambert, R., Leuz, C., & Verrecchia, R. E. 2012. Information asymmetry, information precision, and the cost of capital. Review of Finance, 16 (1): 1–29.

Lamont, O. A. 2012. Go down fighting: Short sellers vs. firms. The Review of Asset Pricing Studies, 2 (1): 1–30.

Laux, C. 2012. Financial instruments, financial reporting, and financial stability. Accounting and Business Research, 42 (3): 239–260.

Loughran, T., & Vijh, A. M. 1997. Do long-term shareholders benefit from corporate acquisitions? The Journal of Finance, 52 (5): 1765–1790.

Mannix, E. A., & Loewenstein, G. F. 1994. The effects of interfirm mobility and individual versus group decision making on managerial time horizons. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 59 (3): 371–390.

Martynova, M., & Renneboog, L. 2006. Mergers and acquisitions in Europe. In L. Renneboog Ed, Advances in Corporate Finance and Asset Pricing. Chapter 2: 15–75. Elsevier: Amsterdam.

Mitchell, M., Pulvino, T., & Stafford, E. 2004. Price pressure around mergers. The Journal of Finance, 59 (1): 31–63.

Porter, M. E. 1992. Capital disadvantage: America’s failing capital investment system. Harvard Business Review, 70 (5): 65–82.

Shao, L., Kwok, C. C. Y., & Zhang, R. 2013. National culture and corporate investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 44 (7): 745–763.

Stein, J. C. 1989. Efficient capital markets, inefficient firms: A model of myopic corporate behavior. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104 (4): 655–669.

Strobl, G. 2013. Earnings manipulation and the cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 51 (2): 449–473.

Thanassoulis, J. 2013. Industry structure, executive pay, and short-termism. Management Science, 59 (2): 402–419.

Zahra, S. A. 1996. Goverance, ownership, and corporate entrepreneurship: The moderating impact of industry technological opportunities. Academy of Management Journal, 39 (6): 1713–1735.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendices

APPENDIX A

Proofs from the Section “Shareholder and technology choice analysis”

Proof of Lemma 1:

-

The market clearing condition is that firms

invest in the risky technology where the “first-best” cut-off type,

invest in the risky technology where the “first-best” cut-off type,  , is determined by the fundamental price and given by

, is determined by the fundamental price and given by

Market clearing requires the borderline firm  to be indifferent between develo** the risky and the safe technology. Hence the fundamental price

to be indifferent between develo** the risky and the safe technology. Hence the fundamental price  is defined implicitly by the relation in (2).

is defined implicitly by the relation in (2).

Rewrite (2) as  The left-hand side is increasing in

The left-hand side is increasing in  The right-hand side is declining in

The right-hand side is declining in  Hence any solution to (2) must be unique. We have

Hence any solution to (2) must be unique. We have  and

and  , hence a fundamental price exists by the Intermediate Value Theorem. □

, hence a fundamental price exists by the Intermediate Value Theorem. □

Proof of Lemma 2:

-

Suppose otherwise that the Board’s strategy was not a cut-off type of this form. Then there must exist two firm types

such that a firm of type

such that a firm of type  would strictly prefer to develop the risky technology, while the firm with higher type

would strictly prefer to develop the risky technology, while the firm with higher type  would strictly prefer to develop the business-as-usual technology. Hence we would have

would strictly prefer to develop the business-as-usual technology. Hence we would have

However, from (3),  as

as  A contradiction to (A9). □

A contradiction to (A9). □

Proof of Proposition 1:

-

We first determine the equilibrium input asset price in part 3. Using the cut-off property of Lemma 2, market clearing (A8) implies firms with type

will develop the risky technology. Each firm will buy 1/P units of the input asset. Applying Bayes rule, the expected type at end

will develop the risky technology. Each firm will buy 1/P units of the input asset. Applying Bayes rule, the expected type at end  of a firm that develops the risky technology is

of a firm that develops the risky technology is

using an integration by parts. Market clearing requires that, in equilibrium, firm type  be indifferent between develo** the risky technology and the business-as-usual technology. Hence, substituting (A10) into (3) and evaluating at type

be indifferent between develo** the risky technology and the business-as-usual technology. Hence, substituting (A10) into (3) and evaluating at type  we require:

we require:

This can be simplified to yield (4). Existence and uniqueness follow by multiplying (4) through by P, noting the right-hand side is declining in P, and applying the Intermediate Value Theorem on prices  in conjunction with assumption (1). This yields part 3.

in conjunction with assumption (1). This yields part 3.

Now consider part 1. Define the function  equal to the right-hand side of (4), so at equilibrium

equal to the right-hand side of (4), so at equilibrium  The sensitivity of the market price to the probability of short-term ownership is

The sensitivity of the market price to the probability of short-term ownership is  By inspection we see that

By inspection we see that  For the denominator we explicitly find

For the denominator we explicitly find

The inequality follows as  Hence

Hence  , and we have the first result.

, and we have the first result.

For part 2 note that firms of type  develop the risky technology, and as

develop the risky technology, and as  this range expands with the probability of short-term ownership.

this range expands with the probability of short-term ownership.

For part 4 at  the market value of the equity of a randomly drawn firm is given as

the market value of the equity of a randomly drawn firm is given as

This follows as firms of type  will develop the risky technology. To raise $1 from equity investors at

will develop the risky technology. To raise $1 from equity investors at  an entrepreneur must offer a proportion 1/V of his firm. The cost of equity capital therefore moves inversely to V. Implicit differentiation of expected firm value yields:

an entrepreneur must offer a proportion 1/V of his firm. The cost of equity capital therefore moves inversely to V. Implicit differentiation of expected firm value yields:

We have shown  and so from (2)

and so from (2)  as

as  Given

Given  , we have

, we have  as required. Hence a greater probability of short-term ownership raises the firm cost of equity capital. □

as required. Hence a greater probability of short-term ownership raises the firm cost of equity capital. □

Proof of Claim 1:

-

In equilibrium at

we must have indifference in

we must have indifference in  valuation between both technologies. Hence from (3)

valuation between both technologies. Hence from (3)  Now consider lowering L. We have

Now consider lowering L. We have  from Proposition 1 part 1 so the denominator shrinks as L falls. The claim follows if

from Proposition 1 part 1 so the denominator shrinks as L falls. The claim follows if  . We have

. We have

as  from Proposition 1 part 2, completing the proof. □

from Proposition 1 part 2, completing the proof. □

APPENDIX B

Manifestations of Short-Termism: Further Details

Elasticity of supply of the input asset

We first develop the study of an elastically supplied input asset and prove Lemma 3. This then allows us to build up to the proof of Proposition 2.

Suppose that the supply, S(P), of the input asset responds to price according to the constant elasticity of supply function:

The supply function (A12) is normalised so that absent short-term shareholders, the fundamental price of the input asset is invariant at the level  given by (2) for any elasticity,

given by (2) for any elasticity,  .Footnote 23 Therefore, absent short-term shareholders, the first best situation would have types

.Footnote 23 Therefore, absent short-term shareholders, the first best situation would have types  investing in the risky technology. We augment (1) and restrict attention to parameters such that:

investing in the risky technology. We augment (1) and restrict attention to parameters such that:

This is sufficient to ensure existence of the equilibrium price for any given elasticity of supply,  .

.

Lemma 3:

-

In an industry with elasticity of supply

and with L short-term shareholders, the critical firm type,

and with L short-term shareholders, the critical firm type,  that just selects the risky technology satisfies

that just selects the risky technology satisfies

Proof of Lemma 3:

-

If the price of the input is P then market clearing with supply function (A12) implies that the critical firm type satisfies

The critical firm type, given L, is indifferent between the risky and safe payoffs and so satisfies, using (3):

From (A15) we have  Using this to substitute for P yields (A14).

Using this to substitute for P yields (A14).

The critical type  exists by applying the Intermediate Value Theorem to (A14) at

exists by applying the Intermediate Value Theorem to (A14) at  and using (A13). For uniqueness note that the left-hand side of (A14) is decreasing in

and using (A13). For uniqueness note that the left-hand side of (A14) is decreasing in  . Differentiation confirms that the right-hand side is increasing in

. Differentiation confirms that the right-hand side is increasing in  □

□

Lemma 3 allows us to establish Proposition 2 demonstrating that the mis-allocation described in Proposition 1 is robust to an elastically supplied input asset.

Proof of Proposition 2:

-

We first confirm the misallocation to the risky-technology:

given in (A8). Evaluating (A14) at

given in (A8). Evaluating (A14) at  yields:

yields:

As the left-hand side of (A14) is decreasing in  while the right-hand side is increasing, we must have

while the right-hand side is increasing, we must have  . Next note that as the price is given in (A15), so

. Next note that as the price is given in (A15), so

Now we show the result. The critical firm type  is given by (A14). Differentiating with respect to

is given by (A14). Differentiating with respect to

It follows that

As we have already shown  . □

. □

Imperfect capital markets

Here we develop the machinery to study mis-estimation by capital markets of the short-term pressure on firms, and build up to the proof of Proposition 3 below.

We use a partial equilibrium analysis, fixing the price of the input asset at P. Given the financial markets’ belief about the probability of short-term ownership,  , the critical firm type,

, the critical firm type,  , that would choose the risky technology would be given implicitly, using (3), by:

, that would choose the risky technology would be given implicitly, using (3), by:

The term  is the market’s

is the market’s  valuation of a firm that has chosen the risky technology. Equation (A16) captures the market’s awareness that short-term shareholders cause the Board to weight the path of the share price as well as the long-run net present value. The term

valuation of a firm that has chosen the risky technology. Equation (A16) captures the market’s awareness that short-term shareholders cause the Board to weight the path of the share price as well as the long-run net present value. The term  is given by:

is given by:

Substituting (A17) into (A16) gives the critical firm type,  , expressed implicitly in terms of fundamental parameters

, expressed implicitly in terms of fundamental parameters  and the market’s belief,

and the market’s belief,  We can therefore calculate the

We can therefore calculate the  ex ante equity value of a randomly drawn firm as:

ex ante equity value of a randomly drawn firm as:

We are now in a position to prove Proposition 3 above.

Proof of Proposition 3:

-

Given market beliefs, the critical firm type for the firm is given by

, where

, where

The market value of a firm at time  will be

will be  if the firm is drawn from

if the firm is drawn from  and r otherwise. Hence the average

and r otherwise. Hence the average  market value is

market value is

The excess return between  and

and  is given by the difference between (A20) and (A18). The value of the firm at

is given by the difference between (A20) and (A18). The value of the firm at  can be written

can be written  Hence the

Hence the  excess return is

excess return is

Now note from (A17) that  Therefore if

Therefore if  then (A16) would yield a contradiction. It follows that

then (A16) would yield a contradiction. It follows that  and so (A16) implies that

and so (A16) implies that  Also from (A19)

Also from (A19)

And so as  we have

we have  Hence we have shown that

Hence we have shown that  Differentiating we have

Differentiating we have

yielding the  excess returns result.

excess returns result.

Now consider the realised values produced at  The market’s beliefs will now be irrelevant as the payoffs can be observed. Firms with types in the range

The market’s beliefs will now be irrelevant as the payoffs can be observed. Firms with types in the range  will have developed the risky technology. On average the payoffs realised will be

will have developed the risky technology. On average the payoffs realised will be

Compared to  the excess return is given by the difference between (A22) and (A18). Using that

the excess return is given by the difference between (A22) and (A18). Using that  this is:

this is:

where the inequality follows as we noted  Hence the excess return is negative. Differentiating we have

Hence the excess return is negative. Differentiating we have

From (A21),  Given

Given  (A19) implies that

(A19) implies that  and so

and so  as required. □

as required. □

Market learning from signals as to firm type

Here we develop a tractable model of the signal of firm type before building up to the proof of Proposition 4.

Recall that in the benchmark model the critical type  indifferent between choosing the risky technology and the risk-free technology is given implicitly by:

indifferent between choosing the risky technology and the risk-free technology is given implicitly by:

Now suppose that before any investment decisions are made  shareholders receive a signal about firm i’s type,

shareholders receive a signal about firm i’s type,  . We assume that this signal gives the true firm type,

. We assume that this signal gives the true firm type,  , with probability s, otherwise it contains no information. The market will use Bayes’ rule to update their beliefs as to firm i’s type:

, with probability s, otherwise it contains no information. The market will use Bayes’ rule to update their beliefs as to firm i’s type:

The presence of the signal will alter the posterior distribution of  and so alter the critical value of

and so alter the critical value of  for firm i to choose the risky technology, to

for firm i to choose the risky technology, to  If

If  and the firm selects the risky technology regardless then the market knows for sure that

and the firm selects the risky technology regardless then the market knows for sure that  is not true, and therefore ignores the signal. If

is not true, and therefore ignores the signal. If  and the risky technology is chosen the market’s expectation of firm i’s type is:

and the risky technology is chosen the market’s expectation of firm i’s type is:

Now we are able to prove Proposition 4.

Proof of Proposition 4:

-

First we show that for sufficiently positive signals, firm misallocation to the risky technology is greater than without a signal. That is

The post signal cut-off

The post signal cut-off  is determined implicitly as:

is determined implicitly as:

Assume the signal is sufficiently strong that  . Evaluate (A26) at

. Evaluate (A26) at

where the inequality follows as we assumed  . Therefore as both sides of (A26) are monotonic with respect to

. Therefore as both sides of (A26) are monotonic with respect to  we must have that

we must have that  as claimed.

as claimed.

Next we show that the misallocation to the risky technology is increasing in the quality of the signal received. Differentiating (A26) with respect to  and using (A25) yields:

and using (A25) yields:

demonstrating the result. □

APPENDIX C

Index of Short-Termism

Figure C1 explains the short-termism measure constructed in equation (5). The examples presented consider ownership stakes over four consecutive quarters for fictitious owners A, B and C who are assumed to own  of the shareholder equity of a given company. Panel (a) demonstrates that volatile share ownership leads to stable short-term measures with no double counting. Panel (b) demonstrates that divestments are captured by equation (5) via the purchasing investor.

of the shareholder equity of a given company. Panel (a) demonstrates that volatile share ownership leads to stable short-term measures with no double counting. Panel (b) demonstrates that divestments are captured by equation (5) via the purchasing investor.

Graphical explanation of short-termism measure.

(a) Volatile shareholder ownership example.

Notes: Only the 20% of the shares that are oscillated between investors B and C are captured as short-term over the 4 quarters. Using equation (5):

(b) Shareholder B selling early example. Notes: At the end of Q4 the firm is owned solely by A and C. The full 50% bought by C is captured as short-term owned over the 4 quarters. Using equation (5):

Summary statistics for the dataset created by this index of short-termism are presented in Table C1.

APPENDIX D

Proofs from the Section “Empirical predictions and evidence”

Proof of Proposition 5:

-

Let

be the density of firm types that announce a merger bid at

be the density of firm types that announce a merger bid at  Using the cut-off property of Lemma 2, market clearing implies firms with type

Using the cut-off property of Lemma 2, market clearing implies firms with type  will develop the risky technology and so will complete the acquisition. The

will develop the risky technology and so will complete the acquisition. The  market value of the equity of a firm at announcement is therefore given by V in (A11). The cumulative abnormal return to the bid announcement is therefore

market value of the equity of a firm at announcement is therefore given by V in (A11). The cumulative abnormal return to the bid announcement is therefore  which gives (6).

which gives (6).

Part 1 follows as  (Proposition 1 part 4). For part 2 we use Claim 1:

(Proposition 1 part 4). For part 2 we use Claim 1:

□

Proof of Proposition 6:

-

Conditional on the risky business model, the market believes the firm’s type lies in

Hence the

Hence the  value is given by

value is given by  However types

However types  choose the risky business model, and so the expected

choose the risky business model, and so the expected  value conditional on the risky business model is in reality

value conditional on the risky business model is in reality  Subtracting one from the other yields (7). Proposition 3 demonstrates

Subtracting one from the other yields (7). Proposition 3 demonstrates  so part 1 follows. Proposition 3 demonstrates that

so part 1 follows. Proposition 3 demonstrates that  given the assumption that

given the assumption that  Hence part 2 follows. □

Hence part 2 follows. □

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thanassoulis, J., Somekh, B. Real economy effects of short-term equity ownership. J Int Bus Stud 47, 233–254 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2015.41

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2015.41

: The analysis would be unchanged if one substituted

: The analysis would be unchanged if one substituted  for

for  .

. share price is not raised here by the absence of short-sellers (

share price is not raised here by the absence of short-sellers ( as to whether the firm is at the top or bottom end of the ability range with respect to the risky technology. The share price is the market’s expected value of the firm’s type conditional on all available public information.

as to whether the firm is at the top or bottom end of the ability range with respect to the risky technology. The share price is the market’s expected value of the firm’s type conditional on all available public information. . The full analysis, as noted above, is given in

. The full analysis, as noted above, is given in  stage would be when the success or failure of incorporating and running the acquired company becomes apparent.

stage would be when the success or failure of incorporating and running the acquired company becomes apparent. the supply is b and the critical firm type is

the supply is b and the critical firm type is  given by (A8).

given by (A8). invest in the risky technology where the “first-best” cut-off type,

invest in the risky technology where the “first-best” cut-off type,  , is determined by the fundamental price and given by

, is determined by the fundamental price and given by such that a firm of type

such that a firm of type  would strictly prefer to develop the risky technology, while the firm with higher type

would strictly prefer to develop the risky technology, while the firm with higher type  would strictly prefer to develop the business-as-usual technology. Hence we would have

would strictly prefer to develop the business-as-usual technology. Hence we would have will develop the risky technology. Each firm will buy 1/P units of the input asset. Applying Bayes rule, the expected type at end

will develop the risky technology. Each firm will buy 1/P units of the input asset. Applying Bayes rule, the expected type at end  of a firm that develops the risky technology is

of a firm that develops the risky technology is we must have indifference in

we must have indifference in  valuation between both technologies. Hence from (3)

valuation between both technologies. Hence from (3)  Now consider lowering L. We have

Now consider lowering L. We have  from Proposition 1 part 1 so the denominator shrinks as L falls. The claim follows if

from Proposition 1 part 1 so the denominator shrinks as L falls. The claim follows if  . We have

. We have and with L short-term shareholders, the critical firm type,

and with L short-term shareholders, the critical firm type,  that just selects the risky technology satisfies

that just selects the risky technology satisfies given in (A8). Evaluating (A14) at

given in (A8). Evaluating (A14) at  yields:

yields: , where

, where The post signal cut-off

The post signal cut-off  is determined implicitly as:

is determined implicitly as:

be the density of firm types that announce a merger bid at

be the density of firm types that announce a merger bid at  Using the cut-off property of Lemma 2, market clearing implies firms with type

Using the cut-off property of Lemma 2, market clearing implies firms with type  will develop the risky technology and so will complete the acquisition. The

will develop the risky technology and so will complete the acquisition. The  market value of the equity of a firm at announcement is therefore given by V in (A11). The cumulative abnormal return to the bid announcement is therefore

market value of the equity of a firm at announcement is therefore given by V in (A11). The cumulative abnormal return to the bid announcement is therefore  which gives (6).

which gives (6). Hence the

Hence the  value is given by

value is given by  However types

However types  choose the risky business model, and so the expected

choose the risky business model, and so the expected  value conditional on the risky business model is in reality

value conditional on the risky business model is in reality  Subtracting one from the other yields (7). Proposition 3 demonstrates

Subtracting one from the other yields (7). Proposition 3 demonstrates  so part 1 follows. Proposition 3 demonstrates that

so part 1 follows. Proposition 3 demonstrates that  given the assumption that

given the assumption that  Hence part 2 follows. □

Hence part 2 follows. □