Abstract

Monolayers of layered materials, such as graphite and molybdenum dichalcogenides, have been the focus of materials science in the last decades. Here, we reveal benign stability and intriguing physical properties in the thinnest monolayer wurtzite (wz) semiconductors, which can be exfoliated from their bulk and stacked to reform the wz crystals. The candidate ZnX and CdX (X = S, Se, Te) monolayers possess low cleavage energy and direct bandgaps, which harbor strongly coupled ferroelectricity and ferroelasticity with low transition barriers, giant in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio, as well as giant Rashba spin splitting, enabling the co-tunability of spin splitting and auxetic magnitudes via multiferroic switching. These wz monolayers can be used as building blocks of devices structures, due to their inherent “self-healable” capacity, which offer more flexibility for semiconductor fabrication and provide a natural platform to probe the interplay of multiple physical effects, bringing light into the rich physics in tetrahedral semiconductors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dating back a century ago, zincblende (zb) and wurtzite (wz) semiconductors arise. Benefiting from the extraordinary electronic properties, these compounds (e.g., CdSe, ZnS etc.) play an important role in the modern semiconductor industry. These semiconductors can be prepared by numerous methods, which are categorized into two paradigms, namely bottom-up and top-down strategies. The former is building larger structures from smaller subcomponents (e.g., individual atoms or molecules) in an additive way, while the latter is carving a larger piece of material in a subtractive manner and acts as the classical approach in the current semiconductor manufacturing to realize abundant devices and integrated circuits1,2. With the requirement of miniaturization and smartness for materials in flexible electronics, the dimensionality of these traditional bulk is expected to be decreased, e.g., one-dimensional (1D) nanowire and two-dimensional (2D) nanosheet. The 2D materials have shown a particularly significant impact in promoting scientific and technological progress, as well as industrial transformation in recent years, which causes them to shine in modern condensed physics, chemistry and material science3. From the viewpoint of crystal structure, 2D materials can be divided into two types, namely layered van der Waals (vdW) materials and non-vdW materials. Most of the currently available monolayer materials are obtained from its layered bulk phase, e.g., MoS24 and black phosphorus5. For the experimentally known 3D crystals, only a small part present the layered structure, while most of them are non-layered. Although a large number of non-vdW materials present rich properties, the realization of their monolayer structures still remains a great challenge. This is because people usually hold the concept that breaking the strong chemical bonds inevitably within the non-vdW crystal is necessary to separate the covalent layer. In contrast, a slightly weak vdW interaction needs to be overcome to cleave the vdW materials. However, the bonding formed between atoms of different planes in non-vdW crystal is non-identical. Therefore, this is thought-provoking—does there exist some kind of “soft” structure in non-vdW materials, that is, the reconstruction of orbital wavefunction bonding at the specific crystal plane force the easy cleaving of monolayer configuration perpendicular to the plane.

Targeting the monolayer limit of conventional non-vdW materials, many efforts including experimental and theoretical investigations have been made. For instance, 2D bilayer graphene-encapsulated GaN can be prepared using the graphene migration-enhanced epitaxial growth method6. The micrometer-sized 2D GaN single crystal has been obtained by the surface-confined nitridation reaction, which presents low thermal conductivity induced by 2D phonon mode, blue-shifted photoluminescence with significantly improved internal quantum efficiency7. Presenting benign structural stability due to the surface distortion, the freestanding single layer ZnSe (four atom thickness) was fabricated by the strategy involving a lamellar hybrid intermediate8. Moreover, oriented attachment growth was applied to synthesize large-scale 2D PbS9. As to theoretical calculation, 2D ultrathin limit III–V, II–VI, and I–VII structures were predicted based on the energy and dynamical judgments10,11,12. From the previous results, we can see that although the experiment approaches6,13 (e.g., the soft colloidal template and migration-enhanced encapsulated growth technique) and theoretical calculations10,11 (energy and phonon stability) proved the stability of 2D non-vdW structure, one key issue, i.e., how the monolayer non-vdW materials can be obtained from their bulk phase, is still unclear. Furthermore, can the thinnest stable monolayer layers be exfoliated from non-layered continuous wz material analogous to the common layered vdW materials? Once the wz monolayer is achieved, can it be used as a building block to form wz crystals reversely by stacking, indicating the potentially “self-healable” capacity. These emergent and fascinating questions motivate us to explore the detailed mechanism hidden in the traditional non-vdW materials.

In this paper, we systematically investigated the cleaving process of wz crystal, predicting a number of stable wz monolayers exfoliated from the (110) plane, whose cleavage energy is analogous to the common vdW materials. The screened candidates ZnX and CdX (X = S, Se, Te) are all semiconductor possessing inherent anisotropic spin splitting around the valence band maximum (VBM) and s-px/y/s-pz orbital interactions due to the interconnected triangular motifs, which leads to strongly coupled ferroelectricity and ferroelasticity with low transition barrier, giant in-plane negative Poisson’s ratio (NPR) and one-dimensional Rashba-type spin. Our study realizes the long-sought synergy of multiferroic, mechanic and spintronic characteristics in wz monolayer and suggests a fresh platform of monolayer semiconductors for further investigations on the intriguing physical properties, as well as device design.

Results

Wurtzite monolayers exfoliated from wz materials

As one typical representative of non-vdW crystal, wz materials, such as ZnS, CdSe etc., have raised great interest during the past decades in academia and industry14,15. We start from the classical wz crystal, aiming to screen the candidates that could form non-vdW monolayer with potentially extraordinary properties (Fig. 1a). The wz crystal possesses hexagonal symmetry with P63mc space group (SG: 186), which has three typical low-index crystal planes, i.e., (100), (110), and (001). We collect 118 binary wz crystals (stoichiometric ratio 1:1) from Materials Project16, 33 kinds of which have been synthesized in the experiment (Supplementary Table 1)17. Then we construct a slab model of these wz structures with different crystal faces (Fig. 1b) and perform a complete structural relaxation for the three planes. Fixing the bottom layers (four layer) of atoms as in the bulk periodic lattice potential field, we stretch the slab from the surface with the amplitude of ∆d = 0.1 Å for the outermost atomic layer and relax the instantaneous strained structure to its stable state. Then we further stretch the strained structure with the above approach until the bond-breaking and layer separation occur. Here we define the energy difference between the layer separating state and the initial stable state as the cleavage energy (Ec) of the wz monolayer. The entire cleavage process can be described by the following formula

where the Ei,0 represents the total energy of the instantaneous stable state (E0,0 is the initial state), Ei,1 indicates the total energy of the relaxed instantaneous structure with ∆d stretched strain. A is the area of the slab. Compared with the Ec obtained by the total energy difference between the initial state and final separated structure, this formula reveals more details during the cleaving process. The critical condition for surface layer separation is determined by Ei,1 ≤ Ei,0, as the surface reconstruction could occur when the structure is cracked, thus leading to a sudden energy loss of ∆E at the critical point (decreasing the total energy of the system). The Ec of the targeted monolayer material can be achieved by summing all the instantaneous strained states until the critical point of layer separation. The surface reconstruction magnitude can be distinguished by the energy loss of ∆E from the critical point to the converged fixed value (Fig. 2a). Summing all the instantaneous strained states until the layer separation, we can obtain the Ec for the wz monolayer. As to the vdW materials, the relatively weak interlayer interaction gives rise to the direct converge of the ∆E instead of drop** dramatically at the critical point, i.e., Ei,1 = Ei,0. The premises for successfully cleaving the non-vdW monolayer are as follows: (i) bond-breaking preferentially occurs at the outermost layer; (ii) Ec is relatively low (generally lower than or equivalent to common vdW materials).

a The material research framework combined with multiferroic, electronic structure, and flexible feature evaluation to screen wz monolayers with potential application in flexible device. The electronic and stability properties of these screened candidates are further calculated using DFT. b Cleavage of the three typical plane (100), (110), and (001) for the wz crystal to form the monolayer structures.

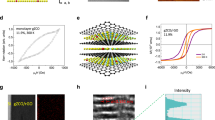

a Cleavage process for (110) plane monolayer ZnX (X = S, Se, Te) with layer thickness from 4L to 8L, which indicates the monotonically increasing cleavage energy with layer thickness and that the energy drops dramatically at the moment of cleaving off due to the interface reconstruction. The inset shows the gradually localized charge (ρ = 0.065 eÅ−3) from S to Te for ZnX. b Atomic bonding landscape from interior to surface for 6L (12 atomic-thickness) ZnSe, which indicates the weakened surface bonding strength with gradually stretching until the separation of the outermost layer. c, d Phonon spectrum and AIMD simulation for monolayer ZnSe, which suggests that the monolayer structure is stable with non-imaginary frequency phonon dispersion and no phase change.

We calculated the cleaving process and Ec from the wz slab with (100), (110), and (001) crystal planes (obtained from the existing 33 kinds of wz crystals). The results show that the Ec of the (100) and (110) monolayers are relatively small (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Figs. 1-2), whose surface layers separate preferentially. In contrast, the Ec of the (001) monolayer is extremely high with the bond-breaking at the middle of the slab. Through analyzing the bonding landscape of the surface and interior atomic wavefunction, we found that the (100), (110), and (001) wz monolayers have opposite bonding strength distributions (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 3), as the bonds of (100)/(110) outer layer are weakened compared to the interior, while the (001) counterpart present opposite, i.e., the bonding strength of the (001) surface atoms is stronger than that of the interior. Therefore, the layer separation of the (100) and (110) monolayers occurs preferentially at the surface, while the (001) slab is cracked at the interior. Indeed, the lattice c-axis direction for the wz structure has significant polarity due to the incomplete cancellation of dipole18, endowing (001) plane atoms with high activity. Once the surface atoms are bonded, the energy will drop significantly, which in turn need to overcome the same energy barrier to separate again. Through evaluating the Ec for a thin layer of wz crystals, we screened 6 “soft” wz monolayers, namely ZnX and CdX (X = S, Se, Te), for which the exfoliation energy (~0.28–1.54 J/m2) is quite small and comparable with that of the vdW materials. As for the other 27 candidates, the Ec is relatively large (e.g., 1.33–3.46 J/m2 for GaP monolayer), thus indicating the unfavorable cleavage. The soften content of the wz monolayers is evaluated as follows: (i) the small values of the highest vibration frequencies f for wz monolayers (4.96–10.91 THz) imply the soft Zn-X and Cd-X (X = S, Se, Te) bonding nature; (ii) compared with Young’s moduli of graphene (1000 N/m)19 and MoS2 (330 N/m)20, the wz monolayers possess remarkably low Young’s moduli (4.10–23.71 N/m), which are lower than those of previously reported 2D materials; (iii) the significantly decreased –ICOHP intensity of the wz monolayer (e.g., 0.65 for ZnSe monolayer) compared with that of the bulk material (1.13 for bulk ZnSe) indicates the weakened covalent bonds. It should be noted that except for the energy drop** at the critical point, the cleavage energy of the monolayer non-vdW crystals will increase with increasing layer thickness, which is different from that of the vdW materials. This is because the energy gain due to the increasing interior covalent bonds makes stretching the structure needs to overcome the higher barrier. The Ec of the vdW materials with weak interlayer interaction is insensitive to the layer thickness (e.g., MoS2). However, as to the vdW materials with strong interaction between layers, the Ec is relatively large and depends on the layer thickness, which obeys the above cleaving process, e.g., Ca2N (Supplementary Fig. 4).

After obtaining the wz monolayer of (100) and (110) planes, we further evaluate their stability. The (110) monolayers possess benign stability as the phonon spectrums present non-imaginary frequency feature and the ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulation between 0 to 10 ps also proves the most stable state for the structure (Fig. 2c, d and Supplementary Figs. 5-6). In contrast, the phonons for the (100) monolayer keep huge imaginary frequencies, which originates from the lack of resilience during the phonon vibration21, leading to the instability for the structure (Supplementary Fig. 7). On the basis of the above analysis for cleaving process and stability, we achieve the (110) wz monolayers (i.e., ZnX and CdX) under the condition of moderate slab thickness (~2–3 nm), which presents relatively low cleavage energy (~0.28–1.54 J/m2) analogous to the vdW materials, e.g., MoS2 (0.29 J/m2)22, graphene (0.37 J/m2)23, and black phosphorus (0.36 J/m2)24. The stability of the (110) wz monolayer stems from the fact that the upper/lower half of the monolayer structure was seen on the upper/lower surface of the slab, and the obtained monolayer is identical to the thinnest slab with 1.95–3.09 Å thickness.

Self-healable wz monolayers as semiconductor building blocks

The covalent bonding nature in wz monolayer endows them with “self-healable” capacity, as the pristine wz structure can be restored automatically if the monolayers are stacked (Supplementary Fig. S8). For instance, when the monolayer ZnSe is stacked onto the monolayer ZnS with decreasing the vertical distance between them, the wavefunction interaction between layers would force the cation to move out of the anion triangle plane and bond with the nearest anions positioned at the other layer, thus leading to the restore of the tetrahedron and wz crystallographic configuration. The vertical distance for the “self-healable” process is ~2 Å for wz monolayer, which is smaller than the monolayer vdW counterparts e.g., MoS2 (3.59 Å) and black phosphorus (3.58 Å). Therefore, using the wz monolayers as building blocks, a series of non-vdW structures can be achieved in such manner, e.g., superlattices, vertically stacked heterostructures, mixed-dimensional device structures (such as a field-effect transistor using heavily doped bulk as electrodes and monolayer as a channel with self-healed tetrahedral bonds between them), twisted non-vdW moire pattern, even the thickness precisely controlled layer, extending the bottom-up strategy into the utilization of monolayers of traditional semiconductors, and offering fresh routes with more flexibility for semiconductor fabrication.

Multiferroicity in wz monolayers

Ferroelectricity is inherent in wz crystal due to the preserved net non-zero polarization along the polar c-axis of the bulk. Here we would like to probe its evolution when the crystal is decreased to monolayer form. There are eight atoms in the wz monolayer unit cell consisting of four cation atoms (Zn, Cd) and four anion atoms (S, Se, Te), which form a triangular motif connected by the vertex of the triangle on the ab plane. The spontaneous ferroelectric (FE) polarization of the wz monolayer lies in the b lattice direction (polar c-axis direction of wz bulk phase) due to the misalignment of cation and anion centers. The sites of cation and anion in FE phase (IC and IA) give rise to the non-zero polarized dipole along -b direction, which can be cancelled if the anion moves to the IIA site along the paths 1–3 with the structure transforming into centrosymmetric (CS) phase with Cmma or Pbcm symmetry [path 1/3: FE (Pca21) → CS (Pbcm); path 2: FE (Pca21) → CS (Cmma)]. We evaluated the energy for one representative of the wz monolayer (i.e., ZnSe) with FE and CS symmetries in Supplementary Fig. S9, which indicates the large energy differences between these two structures with FE and CS (Pbcm) symmetries (0.82/0.49 eV/f.u.). In contrast, the counterpart between FE and CS (Cmma) structure is quite small (0.003 eV/f.u.), suggesting a relatively low transition barrier can be expected along path 2. We thus focus on this transition route and study the electronic properties of these two kinds of phases.

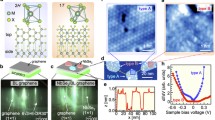

The anion at the IIA site connects the four nearby cations, transforming the triangle in FE structure into tetrahedron in CS phase. Then three sub-paths can be found for the subsequent movement of anion, namely the linear and ‘v’-shaped routes. For convenience, we denote the structure of the top-left panel in Fig. 3a as the initial structure (FEA-1). Along the linear route for the anion, the FEA-1 will change into FEA-2 phase with oppositely polarized dipole along b direction. As to the ‘v’-shaped routes for the anion, the FEA-1 will transform into FEB-1 or FEB-2 phase with ± π/2 rotated polarized dipole and exchange of lattice a/b value [FEA-1/2, a > b; CS, a = b; FEB-1/2, a < b]. The former results in the FE transition due to the inversed triangle motif, while the latter leads to the ferroelastic (FC) transition caused by the ± π/2 rotated triangle motif. In other words, these FE phases (FE-1 and FE-2) and FC phases (FEA and FEB) are bridged smoothly through the CS phase, which leads to the switchable transition between these four phases.

a Detailed phase change process between the FE, FC, and CS structures. The raised magnitude of triangle in either FEA/B-1/2 structure is increased to transform into tetrahedron (CS phase) then decreased to restore the triangle with inversed or π/2 rotated configurations, which forms the multiferroic phase change channel. b, c Phase change barrier for the wz monolayers, indicating the optimal candidates ZnSe and CdSe with benign transition energies between the FEA/B-1/2 and CS phases. Here the ∆E1 and ∆E2 depict the barrier heights for the phase change process.

We evaluated the barrier energy of wz monolayers between the FE and CS phases, as is shown in Figs. 3b, c. Because of the symmetry, the reaction path from either FEA/B-1/2 phase to another one through the CS phase should be identical. The total energies of ZnS and CdS with FE phase are lower than that of the CS counterparts, leading to a large transition barrier (∆E1 = 66.89/50.13 meV/atom, ∆E2 = 25.14/22.08 meV/atom) during the FEA/B-1/CS/FEA/B-2 transition process (∆E1 and ∆E2 denote the barrier heights for the FEA/B-1 → CS and CS → FEA/B-2 phase changing route). In contrast, the total energy differences of ZnSe and CdSe between the FE and CS phases are quite slight, which present relatively low barrier energies (∆E1 = 29.36/27.46 meV/atom, ∆E2 = 30.54/25.12 meV/atom, slightly beyond the room temperature fluctuation kBT). As to the ZnTe and CdTe, the total energy of the CS phase further decreases thus forming a potential well lower than the FE horizontal (∆E1 = 16.79/9.41 meV/atom, ∆E2 = 33.28/25.69 meV/atom). We deem this low barrier energy in wz monolayer to the feasible bonding and bond-breaking within triangles due to the “softened” bonding strength [e.g., the –ICOHP of monolayer FE and CS ZnSe (0.65 and 0.75) is significantly lower than that of the wz bulk (1.13)], which resembles the ‘handshake’ between the cation in the center of the tetrahedron and four adjacent anions. After balancing the transition barrier and individual phase energy for the wz monolayers, we screened ZnX and CdX (X = S, Se) as the potential FE candidates, which present large in-plane polarization (~1.6 × 10−10 C/m) analogous to the outstanding FE materials, e.g., monolayer As, Sb, Bi (0.46–0.75 × 10−10 C/m)

By far, a few mechanisms of NPR have been probed for 2D materials. For instance, the occurrence of NPR in monolayer graphene originates from the interplay between two intrinsic deformation pathways41. Chalcogen p orbitals and the intermetal t2g-bonding orbitals coupling within the triangular pyramid of 1T-type 2D transition metal dichalcogenides leads to in-plane NPR42. Here, we would like to reveal the NPR mechanism in wz monolayer, as originates from the stacking pattern of triangular local motifs. The broken tetrahedron decreases the bonding wavefunction interaction due to the exposed dangling bond, which would force the cation to move into the nearest anion trimer plane spontaneously and increase the s-p orbital coupling to stabilize the structure. The enlarged anion trimer size S and weakened bonding strength (e.g., S = 7.51 Å2 and –ICOHP: 0.65 for monolayer ZnSe) compared with the bulk (7.15 Å2 and 1.13) endow stronger ionic features and “softer” chemical bonds for the monolayer phase (Supplementary Fig. 13). Therefore the local motif of anion and cation transforms from tetrahedron in bulk to triangle in monolayer, which is buckled arranged in basal plane and connected by the vertex of the triangles (Fig. 5a). When one direction is stretched such as along the lattice b, the triangles could be flattened towards the ab plane (θ increases and ∆h decreases as shown in Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 14). A geometric model is built in Fig. 5b to present the condition of occurrence of NPR, which is determined by the expansion magnitude of lattice a. Under tensile strain, if the projections of the two sides r1 and r2 of the adjacent triangles along the lattice a increase, the structure present NPR; if both of the projections decrease, the structure shows PPR; if the projections remain unchanged, the structure exhibits ZPR (zero Poisson’s ratio, such as HgSe in Supplementary Fig. 15). A similar result also holds for compressive strain situations. It is noticed that the NPR doesn’t arise from elongating of bonds between different elements, while it arises from the flattening of the wrinkles in the buckled wz monolayers (Fig. 5a) formed by interconnected triangles (please refer to Supplementary Note 1 for detailed discussion). The NPR value of six kinds of wz monolayers are listed in Table 1, from which we can see the value is to some extend different for the family members and increases gradually with the main group of anion, e.g., ZnS < ZnSe < ZnTe. We deem this originates from the competition between structural deformation and anisotropic bonding orbital coupling. We plot the distribution of all possible orbital combinations for the representative monolayer ZnSe and bonding evolution for ZnX, from which we can see that for one hand, the s and p bonding orbitals of the cation and anion (such as Zn 4s, Se 4s, and Se 4px/y/z) are the main contributors (Fig. 5c); for another the bonding strength shows anisotropic feature for the ZnX (Fig. 5d), as the s-px/y interaction is gradually weakened but the s-pz part is strengthened. This is because the raised triangle in ZnTe presents a larger amplitude due to the longer Zn–Te bonds, which leads to the strongly localized s and dispersive pz states thus forcing the stronger bonding interaction between them (Fig. 5e). In contrast, the localized cation s wavefunction presents a weakened in-plane coupling trend with anion px/y part due to the enlarged bond length. The opposite (anisotropic) bonding distribution rule for the in- and out-of-plane situation determines the NPR value as both the weakened/strengthened s-px/y/s-pz interactions facilitate the structural expansion but the orbital coupling strength is different for wz monolayers.

a Top and side view for wz monolayer, in which we denote three structural parameters, i.e., the sides and angle of adjacently stacked triangles r1/r2 and θ, and the layer height ∆h, here the symbol S denotes the area of the triangle. b Schematic representation for the occurrence of NPR in wz monolayer. c Average of the –ICOHP for all the possible atomic bonding pairs in ZnSe, which indicates the dominating role played by Zn s and Se p states in the orbital coupling. d PDOS for the ZnX with the inset showing the local structural deformation, which suggests the localized/dispersive Zn s/Se pz state. e Anisotropic bonding evolution for in-plane s-px/y and out-of-plane s-pz orbital interactions in ZnX.

Modulation of spin splitting via multiferroic switching

wz monolayer with FE and CS phases are all semiconductors with direct bandgap located at the Γ point of Brillouin zone (Supplementary Fig. S16). Introducing the spin-orbital coupling (SOC), however, strongly modifies the electronic band structures of the wz monolayers. A significant band splitting induced by the SOC can be observed due to the lack of the inversion symmetry, which is mainly visible at the bands along the Γ−X−S high-symmetry lines for FEA-1 (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. S17). However, along the Γ−Y line in which the wave vector k is parallel to the effective electric field associated with the in-plane FE polarization, the bands are double degenerated. Since the electronic states near the Fermi level are important for carrier transport and optical transition behavior, we then focused on the bands near the VBM region. The middle panel of Fig. 6a shows the calculated band structure along the Y−Γ−X line around the VBM for monolayer ZnSe as a representative example of the wz monolayers. At the Γ point, the electronic states are double degenerated due to time reversibility. This doublet splits into singlets when the wave vector k of the bands moves along the Γ−X line. However, the doublet remains for the bands along the Γ−Y line due to the preserved screw rotation and glide plane symmetries. Accordingly, a strongly anisotropic spin splitting is clearly observed around the VBM region. Here, the largest spin splitting along the Γ−X line reaches up to 173 meV for ZnTe monolayer, which is comparable with the splitting energy observed in various monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides (150–460 meV)43,44 and much larger than that of the conventional FE materials Sc2CO2 (16 meV)45, Bi2WO6 (101.9 meV)46, and FE Rashba semiconductors (31–111 meV)47. Similar results also hold for the other wz monolayers except for the two family members ZnS and CdS whose spin splitting magnitude (10/9 meV) along Γ−X line is quite small. The splitting energy observed in the monolayer ZnSe and CdSe with large liner-splitting constants α = 2E/k is certainly sufficient to ensure the proper function of spintronic devices operating at room temperature (Table 1). When the structure transforms into CS phase, the spin is completely degenerate, which can be turned on reversely with the transition from CS to FEA-2 phase (Fig. 6c and right panel of Fig. 6a). Furthermore, the anisotropy can also be flipped with the phase changing from FEA-1/2 to FEB-1/2, as the anisotropic spin degenerate and splitting bands along Γ−Y and Γ−X lines could exchange due to the switching of ferroelasticity (Fig. 6b).

a, b Electronic band structure with SOC for FEA/B-1/2 ZnSe, in which the spin-split bands around VBM region are highlighted. The splitting bands along Γ-Y/X (spin degenerate/splitting) and Γ-X/Y (spin degenerate/splitting) high-symmetry lines around VBM for FEA/B phases indicate the anisotropy flip** feature during the FC phase change process. The spin-up and -down property is inversed accompanied by the FE-1/2 phase change, in which the red and blue arrows indicate Sz (up) and -Sz (down) spin orientation in the momentum space, respectively. c Completely spin degenerated band structure for CS phase. d Switchable spin texture projected to the k space for the upper and lower bands of monolayer ZnSe around VBM, which is expected by reversing the in-plane ferroelectric polarization. e Multiferroic spin transistor with switchable anisotropic transport feature controlled by electric field or strain.

To further clarify the observed anisotropic splitting around the VBM, we show in Fig. 6d the momentum-resolved spin texture for the four FE structures of ZnSe in the entire Brillouin zone. It is found that a uniform pattern of the spin texture is observed around the Γ point, which is verified as 1D Rashba-type spin characteristics. Switchable Rashba spin texture projected to the k space and anisotropic feature for the upper and lower bands of monolayer ZnSe around VBM are expected by reversing the in-plane polarization with π and π/2 degrees through the FE and FC phase transitions. The multiferroic switching meets the pursuit of electric-field-induced elastic deformation for nonvolatile memory devices with ultralow energy consumption48, suggesting that wz monolayers are intrinsic multiferroic materials with strong ferroelectricity and ferroelasticity coupling.

Discussion

Facing such extraordinary properties integrated with wz monolayers, we would like to discuss the significant advantage and what kinds of applications can be expected based on this platform. Ferroelectricity in monolayer materials has attracted significant interest as the ferroelectric order is not only important for probing the interplay between dimensionality and ferroelectric order but also enable different kinds of device49. The theoretical prediction has verified 2D FE materials, including the IV-VI group phosphorene analogues26,50, In2Se351, vdW bilayer/multilayer52,53, distorted 1T MoS254, ionic supersalts55, CuInP2S656, and 2D hybrid perovskite30 and silver and copper monohalides64. These exciting properties have motivated people to explore the possibility of the coexistence of ferroelectricity and ferroelasticity in a single monolayer system. Moreover, the candidate should be scalable for fabrication and compatible with the current silicon-based manufacturing processes. Therefore, the combination of multiferroic coupling, extraordinary electronics and process compatibility has long been one of the primary goals in the study of ferroics for the past years, although its practical application is still hindered by many issues, such as low Curie temperature, unfavorable band structure (e.g., indirect bandgap or small spin splitting), high transition barrier and difficulty for the realization in the experiment.

The current NPR material is mainly focused on the artificial meta-material, which is complicated for the material preparation and device integration process. Moreover, the size of the meta-material limits its working range to a large system presenting high energy dissipation65. The rise of monolayer NPR material in recent years bring light to this embarrassment. For instance, benign ohmic contact can be realized in penta-graphene/graphene heterojunction66. Piezoelectricity67, thermoelectricity68, battery cathode69, and supercapacitor70, can also be achieved. However, by far the available 2D materials with relatively large NPR present indirect band structure (e.g., Be2C35 and PtI238), while the electronic character favorable candidates show small NPR (e.g., GaPS471 and hα Silica37) (Supplementary Table 2).

Inspiringly, the wz monolayers balance these knotty issues very well. Not only the inherent multiferroicity with moderate transition barrier and giant in-plane NPR can be obtained, but also the switchable anisotropic electronic character with 1D Rashba-type spin characteristics can be achieved. For instance, the NPR-multiferroic spin transistor with switchable anisotropic transport feature can be expected (Fig. 6e), which could be controlled by electric field or strain through the multiferroic phase transition and probably work at room temperature due to the moderate transition barrier. More importantly, the “self-healable” capacity of the wz monolayer (stacking and bonding to form the wz structure) provides a knob to fabricate the complex structure, which is beyond the classical bottom-up strategy (epitaxial growth from the initial nuclei). The collected ferroelectrics and ferroelastics in wz monolayers not only enable a simple approach of information manipulation in nonvolatile memory devices, but also provide a long-sought platform to control the multiferroic spintronics freely with electric field or strain.

In summary, we realized the exfoliation of non-vdW wz monolayers with intrinsically strong ferroelectricity and ferroelasticity. Flexible engineering of these wz monolayers is evaluated to monitor the evolution of material’s electronic characteristics, which gives rise to the switchable multiferroic response, giant in-plane NPR and 1D Rashba-type spin characteristics with external strain. The screened candidates ZnX and CdX are predicted to be thermodynamically and kinetically stable, whose synthesis would harbor strong ferroelectricity and ferroelasticity with low transition barrier (~30 meV/atom) and break the record of monolayer in-plane NPR (3 members of them exceed −0.6). All the wz monolayers are semiconductors possessing inherent anisotropic spin splitting around the VBM and s-px/y/s-pz orbital interactions, enabling the co-tunability of spin splitting and auxetic magnitudes. Our study provides the in-depth mechanism of the cleaving process for the non-vdW crystals accompanied with triangle-stacking pattern induced multiferroicity, giant NPR and Rashba spin splitting in wz monolayer, which provide a manufacturing route beyond the classical bottom-up strategy due to the inherent “self-healable” capacity. Moreover, the insight into utilizing the extraordinary synergy for structural multiferroicity, NPR and spin polarization switch successfully interlocks the multiferroics, mechanics and spintronics together within wz monolayer, providing a platform to investigate intriguing physical properties and abundant forms of applications.

Methods

Electronic structure calculation

The electronic structures were calculated by density functional theory (DFT)72 using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) code73,74. The general gradient approximation with Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)75 functional was adopted as the exchange-correlation functional. A plane-wave basis set with the energy cutoff of 500 eV was used to describe electronic wavefunctions. The Zn (3d10 4s2), Cd (4d10 5s2), S (3s2 3p4), Se (3d10 4s2 4p4), and Te (4d10 5s2 5p4) are considered as valence electrons. The total energy convergence criteria were 10−8 eV and all atoms and crystal lattice were fully relaxed until the Hellmann-Feynman force is less than 0.001 eVÅ−1. The Γ-centered k-point mesh of 5 × 5 × 1 was used for the ground state calculations. A vacuum space of more than 20 Å was selected to eliminate the interaction between periodic images. Precise partial density of states projected band structure was calculated by decomposing the s, p, d total orbitals of atoms into individual components along the high-symmetry line in Brillouin zone, which can output the symmetry information and wavefunction constitution of specific k point for each band. The SOC effect was included self consistently in band structure calculations, during which the spin state of the electron’s wavefunction was evaluated by projecting the calculated wavefunction |ψ〉 on the spin and orbital basis of each atomic site. The spin textures were calculated by deducing the spin vector components (Sx, Sy, Sz) in the reciprocal lattice vector k (Y−Γ−X monolayer plane) from the spin density matrix. The Heyd-Scuseria-Ernzerhof hybrid functional method (HSE06)76,77 was used to correct the bandgap values and verify spin splitting magnitude for the wz monolayers. We adopted the modern theory78 of polarization based on the Berry phase method implemented in the VASP code to calculate the ferroelectric polarization. The transition barriers between FE and CS phases were evaluated by using the climbing nudged elastic band (cNEB) method79, during which the crystal symmetry and band structure evolution of every image was carefully depicted. The bonding interaction of the orbital wavefunction was evaluated by the LOBSTER package80. Through scanning the integrated crystal orbital Hamilton population (ICOHP) from surface to interior layer, the evolution of atomic bonding landscape for the (100), (110), and (001) monolayer slab during the stretching process can be obtained, from which the distribution of bonding strength and layer separation position can be easily distinguished. The crystal structures were drawn using the VESTA software81.

Thermodynamic and kinetic stability assessment

The AIMD simulation was carried out to evaluate the thermal stability of wz monolayers. AIMD simulations were performed for 10 ps with NVT ensemble under 300 K, during which the time step is set as 3 fs. The temperature was controlled by using the Nosé-Hoover method82. The thermal stability can be confirmed by whether the pristine monolayer wz configuration would be preserved without phase change and the small fluctuations of energy with time. Phonon spectrums were calculated by using the frozen phonon method, as implemented in PHONOPY code83. The dynamic stability can be determined by the absence of imaginary frequency modes of the phonon spectrum in the whole Brillouin zone. Usually, the limited supercell that is used to calculate the phonon could cause the numerical inaccuracy for some 2D structures (e.g., FeB284 and NbB85 etc.), namely the ~0.1 THz imaginary frequency occurs at the Γ point. These small imaginary phonon modes belong to the acoustic nature in a realistic freestanding system and correspond to a collective vibration mode with a long wavelength approaching infinity, which may induce ripples in the structure, but is not expected to affect the overall structural stability significantly.

Poisson’s ratio evaluation

The Poisson’s ratio for the wz monolayer was calculated by applying the external tensile/compressive strain ε on the crystal lattice. Starting from the initial fully relaxed structure, we stretched/compressed the wz monolayer along the lattice a and b direction, respectively. The strained stable state was realized by fixing the lattice parameter of the deformed direction and relaxing the atoms freely. The Poisson’s ratio was obtained under the relationship between the applied strain εa and the perpendicular deformed strain εb with the formula vab = −εb/εa, which is fitted by the function y = −v1x + v2x2+ v3x3 with the first-order coefficient v1 as the linear Poisson’s ratio. To guarantee the occurrence of the calculated Poisson process, the phonon spectrum was performed to evaluate the stability of the strained structure.