Abstract

Global potent greenhouse gas nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions from soil are accelerating, with increases in the proportion of reactive nitrogen emitted as N2O, i.e., N2O emission factor (EF). Yet, the primary controls and underlying mechanisms of EFs remain unresolved. Based on two independent but complementary global syntheses, and three field studies determining effects of acidity on N2O EFs and soil denitrifying microorganisms, we show that soil pH predominantly controls N2O EFs and emissions by affecting the denitrifier community composition. Analysis of 5438 paired data points of N2O emission fluxes revealed a hump-shaped relationship between soil pH and EFs, with the highest EFs occurring in moderately acidic soils that favored N2O-producing over N2O-consuming microorganisms, and induced high N2O emissions. Our results illustrate that soil pH has a unimodal relationship with soil denitrifiers and EFs, and the net N2O emission depends on both the N2O/(N2O + N2) ratio and overall denitrification rate. These findings can inform strategies to predict and mitigate soil N2O emissions under future nitrogen input scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is the dominant anthropogenic ozone-depleting substance1 and is also a long-lived potent greenhouse gas2. It has a global warming potential about 265–298 times that of carbon dioxide (CO2) and contributes approximately 7% to the overall global warming3,4. Although the N2O concentration in the atmosphere is low at ca. 330 ppb5, it is increasing at an accelerating rate of ca. 0.75~1.0 ppb per year6 because human activities have greatly increased the input of reactive nitrogen (N) in the environment7,8. Agricultural N fertilization, in particular, dominates human-induced N2O emissions5,8,9. Since the proportion of reactive N (Nr) emitted as N2O (i.e., the emission factor, EF) is relatively stable10,11 in neutral soils, the rate of fertilizer N applied has been considered a robust predictor of N2O emission. Therefore, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) uses 1% as the default EF of soils at pH of 6.76 (i.e., IPCC default Tier-1) in estimating N2O emissions10. However, both process-based models and atmospheric inversion studies have recently demonstrated that N2O EFs have significantly increased, which reflects accelerating global N2O emissions in recent decades5,6,12. This suggests that N-application rates are not reliable predictors of N2O emissions.

Increases in N2O EFs have been attributed to the non-linear response of soil N2O emissions to N input6,12,13, building on the premise that high N input exceeds plant N needs and leads to surplus N for microbial N2O production12. Nitrogen applications further induce a higher proportion of N losses via N2O in acidic soils12,14,15 and it is well established that acidity (pH < 5.0) in soil increases the product ratio of [N2O/(N2O + N2)] during denitrification16,17,18. One hypothesized explanation is that pH interferes with the assembly of the N2O reductase17. However, it was also recently shown that soil pH only exerts a control of denitrification product ratio in fertilized soils, while in unfertilized soils, biological controls were more important15. Despite increases in the N2O/(N2O + N2) product ratio of denitrification at low pH, N2O emissions are often low under acidic conditions because acidity suppresses microbial processes that generate N2O18,19,20. In general, raising soil pH through liming to near-neutral level (pH > 6.5) reduces N2O emissions, but raising pH in acidic soils (pH < 5.6) to moderately acidic levels (pH = 5.6–6.0) often increases N2O emissions18,21,22,23. Taken together, these results suggest that soil pH exerts a critical, nonlinear control over N2O emissions12,14,24, highlighting the urgency for a comprehensive, mechanistic understanding of pH effects on soil microorganisms and microbial processes that modulate N2O dynamics.

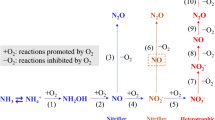

Soil N2O emissions originate mainly from two microbial processes, ammonia oxidation being the first step in nitrification, and denitrification, which is the reduction of nitrate to gaseous N (Supplementary Fig. 1). Although ammonia oxidation by ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) and bacteria (AOB) control the rate-limiting step of nitrification in most terrestrial ecosystems25, denitrification plays a more important role in soil N2O emissions26,27. Since the denitrification process is modular28 with varying genetic capacities for the different reductive steps in the denitrification pathway among denitrifying microorganisms, the composition of the denitrifying community will control N2O emissions. Of special concern is the proportion of the denitrifying community harboring the nosZ gene coding for the N2O reductase that converts N2O to N2 as it is the only known sink for N2O in the biosphere29 (Supplementary Fig. 1). There are two phylogenetically distinct clades in the nosZ phylogeny: nosZI and the recently described nosZII30,31. Not all denitrifiers carry this gene and therefore terminate denitrification with N2O, but there are also non-denitrifying N2O reducers which often possess nosZII29. The ratio of denitrification genes, especially nirK and nirS encoding the known nitrite reductases involved in denitrification, to the nosZ gene abundance is often used as an indication of soil N2O emissions15,32,33, but its relationship with soil pH remains largely unexplored.

There is a lack of a unifying, conceptual framework of soil pH impacts on denitrifying microorganisms and N2O EFs, which critically limits our capacity to predict and mitigate N2O emissions. Here, we address this knowledge gap with two comprehensive, global meta-analyses of N2O emission fluxes and EFs in 539 fertilization experiments and of the relationships between soil pH, denitrification gene abundance estimates, and N2O flux data based on 289 field studies. In addition, three field experiments with acid additions were analyzed to further evaluate the effects of manipulating soil acidity to identify relationships between soil pH and N2O EFs and disentangle the linkages among soil pH, community composition, and activities of denitrifying microorganisms, and N2O EFs.

Results and discussion

Global synthesis of N input and soil pH effects on N2O emission factors

We first investigated how soil N2O EFs related to soil pH and the quantity of N input via fertilization by conducting a meta-analysis based on 539 field fertilization experiments, including 5438 observations of N2O emission fluxes and 3786 EFs records (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Data 1). Data was collected from experiments distributed among croplands, grasslands, and forests across the globe, published between 1980 and 2019.

Geographic locations of sites included in the meta-analysis (a). Relationships between soil pH and coarse EFs (b) or averaged EFs (c), and the relationship between N fertilization rates and coarse EFs (d). A second-order polynomial fit described the hump-shaped relationship between pH and EFs (b, EF = −0.0913pH2 + 1.030 pH−1.826) or averaged EFs at each pH incremental (c, EF = −0.1000 pH 2 + 1.198 pH−2.537), which reached its maximum at pH = 5.6 (b) or 6.0 (c), respectively. Linear regression model with two-sided test was used for the statistical analysis (n = 3562 in b; n = 58 in c; n = 3786 in d). The error bands (shaded areas) in (b and c) represent the 95% confidence intervals around the best-fit regression line, and the blue dashed line in (d) indicates an insignificant relationship. Statistics (adjusted R2 and P-values) for polynomial regression are indicated. The exact P-values: P < 0.001 in (b and c). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The field sites cover soil pH (herein all pH values refer to \({{{{{{\rm{pH}}}}}}}_{({{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}_{2}{{{{{\rm{O}}}}}})}\)) ranging from 2.8 to 9.7, with ca. 58% having a pH of 5.5–7.5 (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Fig. 3). The highest N2O EFs mainly occurred in weak to moderately acidic soils (pH of 5.6–6.5), with an average EF of 1.2% (Fig. 1b, c). While there was a weak but statistically significant, linear relationship between pH and N2O EFs, this regression only explained 2.0% of the variation in EFs (Supplementary Fig. 4; see Supplementary Table 3 for the model selection). Soil N2O EFs had a hump-shaped relationship with soil pH, which reached its maximum at pH 5.6 (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Table 3), and explained 4.0% of the variation in N2O EFs. However, once N2O EFs were averaged across soil pH in increments (0.1 each), the hump-shaped relationship became markedly more apparent and reached its maximum at pH 6.0 and explained 56% of the variation (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig. 5; Supplementary Table 4). These results suggest that interactions between EF and pH diverge around a pH threshold of 5.6–6.0. By contrast, there was no significant linear relationship between N2O EFs and the quantity of N input (Fig. 1d; Supplementary Table 3). Indeed, the averaged EFs gradually increased with N input and reached their highest around 500–600 kg N ha−1 (EF = 1.4%; Fig. 1d; Supplementary Fig. 6). However, the average EFs decreased and remained relatively low in studies with an N input over 600 kg N ha−1 (EF = 1.0%; Fig. 1d; Supplementary Fig. 6). These results are inconsistent with the common belief that high N input or soil N content induces high EFs and reconfirm that N quantity alone cannot sufficiently predict N2O EFs6,12,24. Further, the N2O EFs were significantly higher in acidic tropical soils (pH = 5.5; EFs = 1.1%) than in neutral subtropical (pH = 6.7; EFs = 0.9%) and temperate (pH = 6.9; EFs = 0.8%) soils (Fig. 2a, b), despite significantly lower N input in tropical (170 kg N ha−1) than subtropical (223 kg N ha−1) and temperate (207 kg N ha−1) soils (Fig. 2c). Nevertheless, in tea plantations, all on acidic soils and with high N input (mean = 401 kg N ha−1), N2O EFs positively correlated with both soil pH (Fig. 2d) and the quantity of N input (Fig. 2e), indicating that high acidity reduces N2O emissions. Additionally, our regression analysis showed that soil organic carbon (SOC) content was negatively correlated with soil pH (Supplementary Fig. 7a; R2 = 0.11; P < 0.001), but SOC itself was not significantly related to N2O EFs (Supplementary Fig. 7b), suggesting that SOC may only indirectly affect N2O EFs via soil pH. Moreover, although N2O EFs significantly correlated with mean annual precipitation (MAP), total soil nitrogen (TN), and sand and clay contents, these correlations only explained a low percentage (1–3%) of the variation in N2O EFs (Supplementary Fig. 8). Unlike the hump-shaped relationships observed between soil pH and EFs, our further analyses did not find any significant non-linear relations between N2O EFs and MAP, or sand and clay contents (Supplementary Fig. 8; Supplementary Table 3). There was a hump-shaped relationship between N2O EFs and TN, but it only explained 2% of the variation of N2O EFs (Supplementary Fig. 8; Supplementary Table 3). Taken together, these results indicate that although adequate N levels are required for N2O production, either by nitrification or denitrification, and that multiple soil and climatic factors may affect N2O emissions, soil pH exerts a dominant, non-linear control over N2O EFs.

Average soil pH (a), N2O emission factors (EFs) (b), N fertilization rates (c) in different climate zones, and relationship between N2O EFs and soil pH (d) or N fertilization rates (e) in tea plantations. In a–c bars represent mean ± s.e.m and the sample size ‘n’ represents independent samples. In a–c different letters indicate a statistical significance of the effect based on non-parametric Wilcoxon test (P < 0.05) using the Benjamini and Hochberg (BH) method. The error bands (shaded areas) in (d and e) represent the 95% confidence intervals around best-fit regression line. Statistics (adjusted R2 and P values) for linear regression are indicated. The exact P values: P < 0.001 in (a, c), and P = 0.027 in (b). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Soil acidification effects on soil N-cycling microorganisms and N2O

To disentangle the potential microbial mechanisms governing effects of soil pH per se on N2O EFs, we conducted three field experiments in unfertilized grasslands in which acidity was manipulated (Supplementary Fig. 9). Since none of the experimental sites had received any significant reactive N input (neither N deposition nor N fertilizers)34,35,36, the selection pressure of human-derived N on soil N-cycling microorganisms was negligible. We examined how changes in soil pH (i.e., soil acidification) influenced soil available N, abundance of nitrifier and denitrifier functional groups, and soil N2O emission potential. These experiments were located in three grassland sites with different initial soil pH: a Tibetan alpine meadow (pH = 6.0) near Maqu County, Gansu Province, and a Mongolian steppe (pH = 7.3) in the ** global soil acidification under N deposition. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 4652–4661 (2023)." href="/article/10.1038/s41467-024-46931-3#ref-CR46" id="ref-link-section-d103908969e2818">46. However, the degree of acidification varies locally, which can have different effects on soil N2O emissions. According to our results, N fertilization will induce increased acidification and N2O EFs in soils with weak acidity (pH = 6.0–6.7). Moreover, in several Chinese regions, a considerable proportion of agricultural soils are already highly acidic (4.5 < pH < 5.5), where low pH may indeed inhibit N2O emissions (Fig. 6). However, the high acidity is suppressive to the growth of crop plants, and farmers therefore often increase soil pH through liming, which may increase N2O emissions23. For neutral or alkaline soils (pH > 6.7), particularly those soils with high buffering capacity, N2O emissions are likely less affected because N fertilization may not significantly reduce soil pH over the short term. This is relevant in light of the expected increase in the world population, especially in tropical and subtropical countries where the major population increase will occur, but current N application rates are low47,48. Soils in these regions are typically characterized by low soil fertility and they are moderately to strongly acidic43. Increasing plant-available soil N in these regions will therefore be required to ensure crop productivity and economic profits but will inevitably increase N2O EFs and N2O emissions.

To conclude, our results indicate that soils with high N2O EFs (Figs. 1b and 6) significantly overlap in their pH range with pH optima for most crops (pH = 5.5–6.5)49. This overlap presents a daunting challenge for N2O mitigation through manipulating soil pH, highlighting the need for alternative approaches to reduce N2O emissions. Liming is a common practice in agriculture to reduce toxicity of soil acidity on crop plants44. As low soil pH induces high N2O emission product ratio (N2O:N2) of denitrification17,50, raising soil pH to ca. 6.5 has been proposed as a management tool to reduce N2O emissions50,51,52. However, liming is often economically costly, and farmers tend to only raise soil pH to 5.5–6.053,54, which may, based on our results (Figs. 1 and 6), enhance N2O emissions. Liming also increases soil CO2 emission23,54, offsetting its impact on N2O emissions. Our results highlight the urgency to identify alternative approaches that are practically feasible and conducive to lowering N2O emissions50 and suggest that manipulation of the community composition and activities of N2O-producing and N2O-consuming microbes may provide a promising approach for N2O mitigation. Several unique microbial guilds that dominantly control the N2O sink strength55 have recently been identified, which may be targeted to reduce the denitrification product ratio15. For example, some N2O reductase-carrying bacteria have adapted to highly acidic soils with pH as low as 3.756 and it may be possible to introduce these bacteria into soil to mitigate N2O emissions in highly acidic soils. However, whether those N2O reductase-carrying bacteria can be introduced into slightly acidic soils to effectively mitigate N2O emissions warrants further assessment. In addition, manipulation of N2O-reducing microorganisms might be achieved through crop breeding or cover crop selection because some plants produce root exudates and/or plant metabolites inhibiting nitrifying57,58 and denitrifying59 microorganisms. Further, reducing access of nitrifiers to ammonium through manipulating N sources (e.g., slow-releasing fertilizers)60, supporting nitrate ammonifiers reducing nitrate to ammonium61,62, and enhancing plant N uptake, and/or inhibiting nitrifiers (e.g., nitrification inhibitors) can decrease N2O emissions from both nitrification and denitrification63. Overall, our study provides compelling evidence illustrating that there is a hump-shape relationship between soil pH and N2O EF, leading to highest N2O emissions under moderate soil acidity. These findings suggest that raising pH through liming has limited capacity for N2O mitigation due to multiple biological and economic constraints, and that direct manipulation of N2O-producing and N2O-consuming microbes may provide novel approaches for N2O mitigation under future reactive N input scenarios.

Methods

Meta-analysis 1 of global synthesis of N input and soil pH effects on N2O emission factors (N2O EFs)

The data collection and analysis followed the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (see Supplementary Fig. 2a for further information). We conducted an extensive search for studies of N fertilization and soil N2O emissions published between 1980 and 2019 through the Web of Science, Google Scholar, and the China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database (http://www.cnki.net/). The keywords were used: (i) “nitrogen addition” OR “nitrogen deposition” OR “nitrogen amendment” OR “nitrogen fertilization”; (ii) “soil” OR “terrestrial”; and (iii) “N2O” OR “nitrous oxide”. We also extracted data and re-evaluated all studies from the databases published by Stehfest and Bouwman11, Liu and Greaver64, Shcherbak et al. 12, Liu et al. 65, Wang et al. 14, Charles et al. 66, Deng et al. 67, Maaz et al. 68, Cui et al. 24, and Hergoualc’h et al. 69. In order to avoid selection bias, we extracted peer-review publications with the following criteria: (a) only field studies in which the control and N fertilization treatment sites were located under the same climate, vegetation and soil conditions were included; (b) only chamber-based field experiments conducted in croplands, forests and grasslands were included; (c) studies using nitrification inhibitors were excluded. This yielded a dataset of 5438 observations of N2O emission fluxes from 539 field studies that spanned 42 countries and 570 sites (Fig. 1a; please see Supplementary Data 1). Experiments were grouped into three regions based on absolute latitude: tropical (23.4 °S–23.4 °N), subtropical (23.4–35.0 °S or °N), and temperate (>35.0 °S or °N). For each study, soil properties (i.e., pH, clay, silt and sand content, organic carbon, and total nitrogen) and climate (i.e., mean annual precipitation (MAP) and temperature (MAT)) were directly obtained either from texts and/or tables or extracted from figures using the GetData Graph Digitizer software (ver. 2.22, http://www.getdata-graph-digitizer.com).

Nitrogen fertilization rates and soil N2O emissions obtained from the literature were converted into the unit of kg N ha−1, respectively. Fertilizer-induced N2O emission was then calculated as the difference in soil N2O emission between the fertilization treatment (EN) and the no-fertilizing control (EO). Then the emission factor (EF) of N2O emissions of each fertilization treatment was calculated as the percentage of N2O emission relative to the amount of N fertilization rate (see Eq. 1). This yielded a dataset of 3786 N2O EF values (please see Supplementary Data 1).

To determine the impact of soil pH on N2O EF, pH was divided into 58 groups by 0.1 unit (pH: 2.8–9.7). Soil pH was measured in water in most studies, but it was measured in CaCl2 or KCl in solution in a small number of experiments. We converted soil pH values measured in CaCl2 or KCl into water-based soil pH values, following the method described by Henderson and Bui70 and Kabala et al. 71, respectively. A few studies did not specifically state the reagent used, and we assumed that water was used there. Notably, soil acidity or alkalinity was divided into: ultra-acidic of pH < 3.5, extremely acidic of pH = 3.5–4.4, very strongly acidic of pH = 4.5–5.0, strongly acidic of pH = 5.1–5.5, moderately acidic of pH = 5.6–6.0, slightly acidic of pH = 6.1–6.5, neutral of pH = 6.6–7.3, slightly alkaline of pH = 7.4–7.8, moderately alkaline of pH = 7.9–8.4, and strongly alkaline of pH = 8.5–9.0, following the Soil Science Division Staff (2017)72.

One major issue in the method using the coarse EFs is that the pH increments with more data points are given higher weight than the pH increments with fewer data points. Consequently, the statistical analysis is highly skewed towards the pH increments with a large number of field experiments and measurements. However, this does not provide a fair assessment of the pH effect on N2O EFs. Therefore, we adopted the average method by averaging all the N2O EFs at each pH increment to obtain the mean EF and then giving all the pH increments equal weights. We followed the method used by Linquist et al. 73 and Feng et al. 74 to evaluate the mean EF for the different pH groups (Eqs. (2) and (3).

We used Eq. (2) to calculate the weighted mean values for each pH unit group. In Eq. (2), M is the mean value of EF. Yi is the observation of EF at the ith pH unit group. Wi is the weight for the observations from the ith pH unit group and was calculated with Eq. (3), in which n is the replicates in each field experiment for each study, and o is the total number of observations from the ith pH unit group. At a given pH increment, this approach of weighting assigned more weight to well-replicated field measurements, reporting more precise EF (%) estimates73,74.

Field experiments of soil pH manipulations and their effects on denitrifiers and their activities

Reactive N input affects N-cycling microbes and N2O emissions directly by increasing N availability for nitrification and denitrification and indirectly by inducing soil acidification. In order to determine the direct impact of soil acidification, we manipulated soil pH through adding diluted acids to create a pH gradient in three grassland experiments in the Tibetan Plateau, Inner Mongolian Plateau, and the Yellow Loess Plateau in China. We choose grasslands for three reasons. First, we wanted to assess the effect of soil pH without confounding effects of N fertilization. Unlike most Chinese croplands that have received high amounts of N fertilization41, these grasslands are located in remote areas where there was low ambient N deposition and no N fertilization assuring minimal impact of human-derived N on soil N-cycling microbes34,35,36. Second, since none of the experimental grasslands had received any significant reactive N input (N deposition or N fertilizers), the selection pressure of human-derived N on soil N-cycling microorganisms was negligible. Third, we wanted to have field experiments on acidic, neutral, and alkaline soils that also have decent amounts of available soil N. Available soil N (particularly NO3−) in other unfertilized soils, like forest soils, is very low and likely constrains N-cycling microbes75. Moreover, grasslands potentially contribute 20% of total N2O flux to the atmosphere at the global scale76,77. A considerable proportion of global grasslands are under moderate to intensive management, and it is expected that more grasslands will be under fertilization, likely increasing N2O emissions77.

The three acid addition experiments were established in three grasslands with distinct climatic and soil conditions (Supplementary Table 1; see Supplementary Data 2). The first experiment was set up in an alpine meadow at Gansu Gannan Grassland Ecosystem National Observation and Research Station (33°59′N, 102°00′E, ca. 3538 m a.s.l.) in Maqu county, Gannan Prefecture, Gansu Province, China. Over the last forty years, the MAP and MAT at this site were at 620 mm and 1.2 °C, respectively. The soil was categorized as Cambisol (FAO taxonomy) and moderately acidic with a pH value of ca. 6.0 with moderate pH buffering capacity35. The second experiment took advantage of an existing study on a steppe ecosystem at the Inner Mongolia Grassland Ecosystem Research Station of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (43°38′N, 116°42′E, 1250 m a.s.l.) near **lin city, Inner Mongolia, China. The MAT at this site was 0.3 °C with the lowest in January (−21.6 °C) and the highest in July (19.0 °C). It has had a MAP of 346.1 mm with the majority (ca. 80%) occurring in summer (June to August). It had a dark chestnut soil (Calcic Chernozem according to ISSS Working Group RB, 1998) with a nearly neutral pH value (ca. 7.3) and with high sand content and low pH buffering capcity34. The third experiment was in a semi-arid grassland at the Yunwu Mountains Natural Preserve (36°10′−36°17′N, 106°21′−106°27′E, 1800–2100 m a.s.l.) on the Loess Plateau, Guyuan, Ningxia, Northwest China. This site has a typical semiarid climate, and the mean annual rainfall was about 425 mm with about two-thirds (60–75%) falling in July-September. Over the last three decades, this site had a MAT of 7.0 °C (the lowest in January at −14 °C and the highest in July at 22.8 °C). The soil was a montane gray-cinnamon type classified as a Calci-Orthic Aridisol or a Haplic Calcisol in the Chinese and FAO classification, and alkaline with a pH of 8.0 and high pH buffering capacity36.

At each site, a single factor of acid (sulfuric acid) addition experiment was designed. To minimize any potential direct acid damage to living plants and soil organisms, the specific dose of concentrated sulfuric acid (98%) needed for each plot was first diluted into 60 L of tap water and then sprayed into each plot. Equal amounts of water only were added to the no-acid controls (A0).

At the Gannan alpine site, the acid addition experiment was established in 2016 with five levels of acid addition78: 0 (the control, A0), 1.32 (A1), 5.29 (A2), 9.25 (A3), and 14.53 (A4) mol H+ m−2 yr−1. Twenty plots (2 m × 2 m each) were then arranged in a randomized block design including four replicate blocks separated by 1 m buffer zones. Diluted sulfuric acid solution was applied twice each year (half of the designed dosage each time) in early June and late September of 2016, late April and late September of 2017, and late April 2018. At the Inner Mongolia steppe site, the acid experiment was initiated in 2009 with seven gradients of acid addition79: 0, 2.76, 5.52, 8.28, 11.04, 13.80, and 16.56 mol H+ m−2 yr−1. The experiment was randomly positioned in a block design with 5 replicate blocks, leading to a total of 35 field plots (2 m × 2 m each). Diluted acid solution at the designed concentration was added to each plot in early September 2009, early June 2010, and early September 2010. Soil pH in all treatments stabilized and no additional acid has been added since 201079. For this study, we randomly chose four replicate field plots of five treatments, 0 (the control, A0), 2.76 (A1), 5.52 (A2), 11.04 (A3), and 16.56 (A4) mol H+ m−2 yr−1, to investigate the impact of soil acidification on soil nitrifiers, denitrifiers and denitrification. The acid experiment at the Guyuan site was established in 2016 with 30 plots (2 m × 2 m each) using a randomized block design80. It had five levels of acid additions with six replicate blocks separated by 1 m walkways. The five levels of acid additions were: 0 (the control, A0), 0.44 (A1), 1.10 (A2), 7.04 (A3), and 17.61 (A4) mol H+ m−2 yr−1, respectively. Diluted acid solution was applied twice each year (half each time) in early June and late September of 2016, late April and late September of 2017, and early May 2018.

In mid-August 2018 when plant biomass peaked, three soil cores (5.0 cm dia.) were collected at 0–10 cm depth from each plot at both Gannan and Guyuan sites, and then mixed to form a composite sample per plot. For the Inner Mongolia site, soil samples were collected in the same way in early September 2020. Composited soil samples collected in field were placed on ice in coolers, and sent by express mail to the laboratory in Nan**g, China. All soil samples were first sieved through a mesh (2 mm) to remove rocks and dead plant materials. A small subsample (ca. 50 g) of each field soil sample was immediately stored at −20 °C for molecular analyses, and the remainder was kept at 4 °C in the refrigerator for later chemical and microbial analyses that were all initiated within 2 weeks. Soil pH in a soil-to-water (1:5, w/w) slurry was measured on an Ultramete-2 pH meter (Myron L. Company, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Inorganic NH4+-N and NO3−-N were extracted with 0.5 M K2SO4, and their concentrations in the extracts were quantified on a continuous flow injection auto-analyzer (Skalar SAN Plus, Skalar Inc., The Netherlands)35. For each soil sample, 0.3 g (dry soil equivalent) frozen soil was used to extract total genomic DNA with PowerSoil DNA kits (MoBio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The DNA quantity and quality were determined by a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). The copy numbers of AOA-amoA, AOB-amoA, nirK, nirS, and nosZI genes were determined using the Real-Time quantitative PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The primer sets of crenamoA23F/crenamoA616r (ATGGTCTGGCTWAGACG/GCCATCCATCTGTATGTCCA)81, amoA-1F/amoA-2R (GGGGTTTCTACTGGTGGT/CCCCTCGGAAAGCCTTCTTC)82, nirK876/nirK1040 (ATYGGCGGVAYGGCGA/GCCTCGATCAGRTTRTGGTT)83, nirSCd3aF/nirSR3cd (AACGYSAAGGARACSGG/GASTTCGGRTGSGTCTTSAYGAA)84, and norZ1f/norZ1R (WCSYTGTTCMTCGAGCCAG/ATGTCGATCARCTGVKCRTTYTC)85 were used for the amplification of AOA-amoA, AOB-amoA, nirK, nirS, and nosZI gene, respectively. Each qPCR reaction (20 µL volume) was performed with 10 µL SYBRs Premix Ex TaqTM (Takara, Dalian, China), 1 µL template DNA corresponding to 8–12 ng, 0.5 µL of each primer, 0.5 µL bovine serum albumin (BSA, 5 mg mL−1) and 7.5 µL distilled deionized H2O (ddH2O). The standard curve for determining the gene copy number was developed using the standard plasmids of different dilutions as a temperate. The standard plasmids were generated from the positive clones of the 5 target genes, which were derived from the amplification of the soil sample55. The amplification efficiency of the qPCR assays ranged from 90 to 100% with R2 > 0.99 for the standard curves. We checked potential qPCR reaction inhibition via the amplification of a known amount of the pGEM-T plasmid (Promega) with T7 and SP6 primers, adding to the extracts of DNA samples or water. No amplification reaction inhibitions in the samples were detected.

We did not directly monitor soil N2O fluxes in the field, mainly because the field sites were remote. Instead, microcosm incubation experiments were conducted to determine potential soil N2O emissions. For each soil sample, field soil (20.0 g dry mass equivalent) was placed into a 125-mL dark bottle, and deionized water was added to adjust soil moisture to ca. 70% water-filled pore space (WFPS), creating a moisture condition conducive for denitrifiers and denitrification33,86. The high soil moisture content favored anaerobic processes since O2 diffusion into the soil was restricted and effects of oxygen should be negligible. All bottles were loosely covered with fitting lids and incubated in a dark incubator at 20 °C. It is worth mentioning that both nitrification and denitrification processes produce N2O, but optimum N2O emissions from denitrification often occur at 70–80% WFPS33,86. Also, our results showed that soil pH had a linear relationship with soil nitrifiers (Supplementary Fig. 12) and the high soil moisture suppressed nitrification. Thus, the design of the incubation experiments targeted N2O from anaerobic processes like denitrification, and N2O emissions from nitrification or other aerobic processes were not considered33.

To determine the N2O emissions, gas samples were taken from the headspaces of the incubation bottles as described by Zhang et al. 35. More specifically, all incubation bottles were flushed with fresh air (2 min each) prior to the gas sampling, then immediately sealed and incubated for 6 h in the dark. A gas sample of 15 mL was taken from the headspace of each incubation bottle and was immediately transferred into a vial for gas chromatograph (GC) measurement. After gas sampling, all incubation bottles were loosely covered until the next gas sampling to ensure minimum water loss. Gas sampling was conducted 5 times, respectively, at 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after the incubation initiation. N2O concentrations in the sampling vials were determined within 24 h after the sampling collection on a GC equipped with an electron capture detector (ECD) (GC-7890B, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The N2O fluxes were calculated using the formula35:

where F is the soil N2O gas flux rates (µg N kg−1 soil h−1), \(\rho\) is the standard state gas density (kg m−3), V is the bottle volume (L),\(\Delta C\) is the difference in N2O concentration (ppm) between two samples (0 and 6 h), T is the incubation temperature at 20 °C, and W is the dry weight of soil (kg).

We further determined soil potential denitrification activities (PDA), using the modified acetylene (C2H2) inhibition technique55,87. For each field soil sample, two sub-samples (each 5.0 g dry soil equivalent) were respectively put into two 100 mL sterile serum bottles. Then, 8 mL of N- and C-containing solution (KNO3 at 50 mg NO3−-N g−1 dry soil, glucose, and glutamic acid, each at 0.5 mg C g−1 dry soil) was added to create a soil slurry conducive for denitrification. To measure the PDA, 10% C2H2 was injected into one bottle to inhibit N2O reductase activity so that the N2O produced was not reduced to N2. In the other bottle, no C2H2 was added so that all enzymes of denitrification remained active and the N2O detected was the net difference between the production and consumption of N2O55. All serum bottles were incubated in dark at 25 °C with agitation at 180 rpm. Gas samples (10 mL) were taken from the headspace at 2, 4 and 6 h after the beginning of the incubation for determination of N2O concentrations on a GC (GC-7890B, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Meta-analysis 2 of relationships between soil pH and N2O-producing or N2O-consuming denitrifying microorganisms

Similar to Meta-analysis 1, the data collection and analysis were also carried out according to the PRISMA guidelines (Supplementary Fig. 2b). We conducted an extensive search in Web of Science and Google Scholar for studies in which nirK-, nirS- and nosZ (clade I and II) had been quantified with the two sets of search terms: (1) nirK, nirS or nosZ gene, and (2) soil or terrestrial. In total, the search resulted in ca. 1539 article hits in December 2021. All articles were carefully read through to select those based on field studies, whereas those based on microcosm studies were excluded. There were 286 published papers that met our criteria. We also included the data from the three field acid addition experiments described above. Special attention was also directed towards checking whether nosZ clade I, nosZ clade II or both were quantified. Only 26 published studies quantified nosZII and, among these, only nine also reported soil N2O emissions in the field (see Supplementary Data 3 for detail). Therefore, the gene nosZ in the dataset in this study only refers to nosZ clade I. Thus, the final dataset contained data from 501 sites reported by 289 studies, and included 1347, 1265, and 1287 abundance estimates of nirK, nirS and nosZI genes, respectively (see Supplementary Data 3 for detail).

We extracted data either from tables, texts or from figures using the GetData Graph Digitizer software (ver. 2.22; http://getdata-graph-digitizer.com). For each article, we extracted the following information for our analysis: the abundance of nirK, nirS, nosZI and nosZII genes (copy numbers per g soil), soil pH, and depth of collected soils. Latitude, altitude, MAP and MAT of the experimental sites were also recorded. All information of N2O emissions (N2O emission rates and/or cumulative N2O emissions) was extracted. Because various publications reported the results of N2O emissions in different units, we converted all N2O emission rates into the unit of μg N m−2 h−1. Data were log-transformed to meet statistical tests assumptions (if necessary). In the literature, most data of gene abundances were presented in the form of log-transformed numbers, we first transformed them back to real numbers and obtained the average gene abundances for each pH increment, and then again log-transformed. Similar to Meta-analysis 1, we examined the relationships between soil pH and abundances of denitrifying microorganisms, using both coarse abundance and averaged abundance of each functional group of denitrifiers at each pH increment.

Statistical analyses

In Meta-analysis 1, we examined potential linear or quadratic relationships between N2O EFs and soil pH, MAP, MAT, soil sand, silt and clay content, SOC or TN. In Meta-analysis 2, we examined potential linear and quadratic relationships between soil pH and the abundance of nirK-, nirS-, nosZI-type denitrifiers, or the (nirK+nirS)/nosZI ratio. The model goodness of fit was evaluated with the Akaike information criterion (AICc) where a lower AICc value represents a model with a better fit88,89. In general, differences in AICc higher than 2 indicate that models are substantially different88. Information on the AICc index was obtained using the package MuMIn from R90. Given the large number of samples included in the meta-analyses, we interpreted the statistical significance of individual predictors using a conservative α of 0.001 following model selection by AICc. In Meta-analysis 1, we did a non-parametric alternative of Kruskal–Wallis analysis together with Pairwise Wilcox test to determine the differences in soil pH, N2O EFs, and N fertilization rate among different climate zones.

For the field experiments, we used linear mixed-effects (LME) models to determine the effects of acid addition on the response variables at each site, treating the acid treatments as fixed effects and block as a random effect. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan’s multiple-range tests were used to compare the means among acid addition levels across all response variables. Then, we examined the relationships between soil pH and N2O emissions, PDA, N2O/(N2O + N2) ratio or the (nirK+nirS)/nosZI ratio across all three field sites, using linear or quadratic regression. We used the Akaike information criterion (AICc) to evaluate the model’s goodness of fit88. All analyses were conducted in R (version 4.1.1)91.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available in Supplementary Data 1–3.xlsx and online in the Figshare database (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24591522).

Code availability

The code is available in the Figshare database (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24591522).

References

Ravishankara, A. R., Daniel, J. S. & Portmann, R. W. Nitrous oxide (N2O): the dominant ozone-depleting substance emitted in the 21st century. Science 326, 123–125 (2009).

Myhre, G. et al. Anthropogenic and natural radiative forcing. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, United Kingdom, New York, NY, USA, 2013).

Montzka, S. A., Dlugokencky, E. J. & Butler, J. H. Non-CO2 greenhouse gases and climate change. Nature 476, 43–50 (2011).

Butterbach-Bahl, K. & Wolf, B. Greenhouse gases: Warming from freezing soils. Nat. Geosci. 10, 248–249 (2017).

Tian, H. et al. A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks. Nature 586, 248–256 (2020).

Thompson, R. L. et al. Acceleration of global N2O emissions seen from two decades of atmospheric inversion. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 993–998 (2019).

Galloway, J. N. et al. Transformation of the nitrogen cycle: recent trends, questions, and potential solutions. Science 320, 889–892 (2008).

Davidson, E. A. The contribution of manure and fertilizer nitrogen to atmospheric nitrous oxide since 1860. Nat. Geosci. 2, 659–662 (2009).

Mosier, A. et al. Closing the global N2O budget: nitrous oxide emissions through the agricultural nitrogen cycle. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 52, 225–248 (1998).

De Klein, C. et al. in IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, Prepared by the National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme Vol 4 (eds Eggleston, H. S., Miwa, K., Srivastava, N. & Tanabe, K.) (IGES, Hayama, Japan, 2006).

Stehfest, E. & Bouwman, L. N2O and NO emission from agricultural fields and soils under natural vegetation: summarizing available measurement data and modeling of global annual emissions. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 74, 207–228 (2006).

Shcherbak, L., Millar, N. & Robertson, G. P. Global metaanalysis of the nonlinear response of soil nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions to fertilizer nitrogen. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 111, 9199–9204 (2014).

Gerber, J. S. et al. Spatially explicit estimates of N2O emissions from croplands suggest climate mitigation opportunities from improved fertilizer management. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 3383–3394 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Soil pH as the chief modifier for regional nitrous oxide emissions: new evidence and implications for global estimates and mitigation. Glob. Change Biol. 24, e617–e626 (2018).

Jones, C. M., Putz, M., Tiemann, M. & Hallin, S. Reactive nitrogen restructures and weakens microbial controls of soil N2O emissions. Commun. Biol. 5, 273 (2022).

Firestone, M. K., Firestone, R. B. & Tiedje, J. M. Nitrous oxide from soil denitrification: Factors controlling its biological production. Science 208, 749–751 (1980).

Liu, B., Mørkved, P. T., Frostegård, Å. & Bakken, L. R. Denitrification gene pools, transcription and kinetics of NO, N2O and N2 production as affected by soil pH. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 72, 407–417 (2010).

Bakken, L. R., Bergaust, L., Liu, B. & Frostegård, Å. Regulation of denitrification at the cellular level: a clue to the understanding of N2O emissions from soils. Phil. Trans. R Soc B. 367, 1226–1234 (2012).

Hall, S. J. & Matson, P. A. Nitrogen oxide emissions after nitrogen additions in tropical forests. Nature 400, 152–155 (1999).

Šimek, M. & Cooper, J. E. The influence of soil pH on denitrification: Progress towards the understanding of this interaction over the last 50 years. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 53, 345–354 (2002).

Clough, T. J., Sherlock, R. R. & Kelliher, F. M. Can liming mitigate N2O fluxes from a urine-amended soil? Aust. J. Soil Res. 41, 439–457 (2003).

Papen, H. & Butterbach-Bahl, K. A 3-year continuous record of nitrogen trace gas fluxes from untreated and limed soil of a N-saturated spruce and beech forest ecosystem in Germany. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 104, 18487–18503 (1999).

Wang, Y. et al. Potential benefits of liming to acid soils on climate change mitigation and food security. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 2807–2821 (2021).

Cui, X. et al. Global map** of crop-specific emission factors highlights hotspots of nitrous oxide mitigation. Nat. Food 2, 886–893 (2021).

Prosser, J. I. & Nicol, G. W. Archaeal and bacterial ammonia oxidisers in soil: the quest for niche specialisation and differentiation. Trends Microbiol. 20, 523–531 (2012).

Firestone, M. K. & Davidson, E. A. in Exchange of Trace Gases Between Terrestrial Ecosystems and the Atmosphere (eds Andreae, M. O. & Schimel, D. S.) (Wiley, Chichester, UK, 1989).

Liang, D. & Robertson, G. P. Nitrification is a minor source of nitrous oxide (N2O) in agricultural landscapes and declines with increasing management intensity. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 5599–5613 (2021).

Graf, D. R. H., Jones, C. M. & Hallin, S. Intergenomic comparisons highlight modularity of the denitrification pathway and underpin the importance of community structure for N2O emissions. PLoS ONE 9, e114118 (2014).

Hallin, S., Philippot, L., Löffler, F. E., Sanford, R. A. & Jones, C. M. Genomics and ecology of novel N2O-reducing microorganisms. Trends Microbiol. 26, 43–55 (2018).

Sanford, R. A. et al. Unexpected nondenitrifier nitrous oxide reductase gene diversity and abundance in soils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109, 19709–19714 (2012).

Jones, C. M., Graf, D. R. H., Bru, D., Philippot, L. & Hallin, S. The unaccounted yet abundant nitrous oxide reducing microbial community - a potential nitrous oxide sink. ISME J. 7, 417–426 (2013).

Hu, H. W., Chen, D. & He, J. Z. Microbial regulation of terrestrial nitrous oxide formation: understanding the biological pathways for prediction of emission rates. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 39, 729–749 (2015).

Qiu, Y. et al. Shifts in the composition and activities of denitrifiers dominate CO2 stimulation of N2O emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 11204–11213 (2019).

Bai, Y. et al. Tradeoffs and thresholds in the effects of nitrogen addition on biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: evidence from inner Mongolia Grasslands. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 358–372 (2010).

Zhang, Y. et al. Simulated warming enhances the responses of microbial N transformations to reactive N input in a Tibetan alpine meadow. Environ. Int. 141, 105795 (2020).

Bai, T. et al. Interactive global change factors mitigate soil aggregation and carbon change in a semi-arid grassland. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 5320–5332 (2020).

Čuhel, J. et al. Insights into the effect of soil pH on N2O and N2 emissions and denitrifier community size and activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 1870–1878 (2010).

Qu, Z., Wang, J., Almoy, T. & Bakken, L. R. Excessive use of nitrogen in Chinese agriculture results in high N2O/(N2O+N2) product ratio of denitrification, primarily due to acidification of the soils. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 1685–1698 (2014).

Prosser, J. I. Autotrophic nitrification in bacteria. Adv. Microbiol. Physiol. 30, 125–181 (1989).

Gubry-Rangin, G. et al. Niche specialization of terrestrial archaeal ammonia oxidizers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 108, 21206–21211 (2011).

Guo, J. H. et al. Significant acidification in major Chinese croplands. Science 327, 1008–1010 (2010).

Signor, D., Cerri, C. E. P. & Conant, R. N2O emissions due to nitrogen fertilizer applications in two regions of sugarcane cultivation in Brazil. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 015013 (2013).

Slessarev, E. W. et al. Water balance creates a threshold in soil pH at the global scale. Nature 540, 567–569 (2016).

Fageria, N. K. & Baligar, V. C. Ameliorating soil acidity of tropical Oxisols by liming for sustainable crop production. Adv. Agron. 99, 345–399 (2008).

Bowman, W. D., Cleveland, C. C., Halada, L., Hreško, J. & Baron, J. S. Negative impact of nitrogen deposition on soil buffering capacity. Nat. Geosci. 1, 767–770 (2008).

Chen, C., ** global soil acidification under N deposition. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 4652–4661 (2023).

Godfray, H. C. J. et al. Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 327, 812–818 (2010).

Vitousek, P. M. et al. Nutrient imbalances in agricultural development. Science 324, 1519–1520 (2009).

Fageria, N. K., Baligar, V. C. & Jones C. A. Growth and Mineral Nutrition of Field Crops (CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, USA, 2011).

Bakken, L. R. & Frostegård, Å. Emerging options for mitigating N2O emissions from food production by manipulating the soil microbiota. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 47, 89–94 (2020).

Hénault, C. et al. Management of soil pH promotes nitrous oxide reduction and thus mitigates soil emissions of this greenhouse gas. Sci. Rep. 9, 20182 (2019).

Rees, R. M. et al. Mitigating nitrous oxide emissions from agricultural soils by precision management. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 7, 75–80 (2020).

Edmeades, D. C., Pringle, R. M., Mansell, G. P. & Shannon, P. W. Effects of lime on pasture production on soils in the North Island of New Zealand; 4. Predicting lime responses. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 27, 371–382 (1984).

Goulding, K. W. T. Soil acidification and the importance of liming agricultural soils with particular reference to the United Kingdom. Soil Use Manag. 32, 390–399 (2016).

Jones, C. et al. Recently identified microbial guild mediates soil N2O sink capacity. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 801–805 (2014).

Lycus, P. et al. Phenotypic and genotypic richness of denitrifiers revealed by a novel isolation strategy. ISME J. 11, 2219–2232 (2017).

Subbarao, G. V. et al. Enlisting wild grass genes to combat nitrification in wheat farming: a nature-based solution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 118, e2106595118 (2021).

Coskun, D., Britto, D. T., Shi, W. & Kronzucker, H. J. Nitrogen transformations in modern agriculture and the role of biological nitrification inhibition. Nat. Plants 3, 17074 (2017).

Bardon, C. et al. Evidence for biological denitrification inhibition (BDI) by plant secondary metabolites. N. Phytol. 204, 620–630 (2014).

Akiyama, H., Yan, X. Y. & Yagi, K. Evaluation of effectiveness of enhanced-efficiency fertilizers as mitigation options for N2O and NO emissions from agricultural soils: meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 1837–1846 (2010).

Saghaï, A., Pold, G., Jones, C. M. & Hallin, S. Phyloecology of nitrate ammonifiers and their importance relative to denitrifiers in global terrestrial biomes. Nat. Commun. 14, 8429 (2023).

Hallin, S. & Saghaï, A. Can nitrate reducing ammonifiers increase nitrogen retention in soil and support ammonium-based crop** systems? J. Sustain. Agric. Environ. 2, 541–545 (2023).

Lam, S. K., Suter, H., Mosier, A. R. & Chen, D. Using nitrification inhibitors to mitigate agricultural N2O emission: a double-edged sword? Glob. Change Biol. 23, 485–489 (2016).

Liu, L. & Greaver, T. L. A review of nitrogen enrichment effects on three biogenic GHGs: the CO2 sink may be largely offset by stimulated N2O and CH4 emission. Ecol. Lett. 12, 1103–1117 (2009).

Liu, S. et al. A meta- analysis of fertilizer- induced soil NO and combined with N2O emissions. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 2520–2532 (2017).

Charles, A. et al. Global nitrous oxide emission factors from agricultural soils after addition of organic amendments: a meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 236, 88–98 (2017).

Deng, L. et al. Soil GHG fluxes are altered by N deposition: New data indicate lower N stimulation of the N2O flux and greater stimulation of the calculated C pools. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 2613–2629 (2020).

Maaz, T. M. et al. Meta-analysis of yield and nitrous oxide outcomes for nitrogen management in agriculture. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 2343–2360 (2021).

Hergoualc’h, K. et al. Improved accuracy and reduced uncertainty in greenhouse gas inventories by refining the IPCC emission factor for direct N2O emissions from nitrogen inputs to managed soils. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 6536–6550 (2021).

Henderson, B. & Bui, E. N. An improved calibration curve between soil pH measured in water. Aust. J. Soil Res. 40, 1399–1405 (2002).

Kabala, C., Musztyfaga, E., Galka, B., Labunska, D. & Manczynska, P. Conversion of soil pH 1:2.5 KCl and 1:2.5 H2O to 1:5 H2O: conclusions for soil management, environmental monitoring, and international soil databases. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 25, 647–653 (2016).

Ditzler, C., Scheffe, K. & Monger H. C. Soil Science Division Staff. Soil Survey Manual (eds Ditzler, C., Scheffe, K. & Monger, H. C.) USDA Handbook 18 (Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 2017).

Linquist, B., van Groenigen, K. J., Adviento-Borbe, M. A., Pittelkow, C. & van Kessel, C. An agronomic assessment of greenhouse gas emissions from major cereal crops. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 194–209 (2012).

Feng, J. et al. Impacts of crop** practice on yield-scale greenhouse gas emission from rice fields in China: a meta-analysis. Agric. Water Manage. 164, 220–228 (2013).

Stark, J. M. & Hart, S. C. High rates of nitrification and nitrate turnover in undisturbed coniferous forests. Nature 385, 61–64 (1997).

Dangal, S. R. S. et al. Global nitrous oxide emissions from pasturelands and rangelands: magnitude, spatiotemporal patterns and attribution. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 33, 200–222 (2019).

Chang, J. et al. Climate warming from managed grasslands cancels the cooling effect of carbon sinks in sparsely grazed and natural grasslands. Nat. Commun. 12, 118 (2021).

Wang, P. et al. Soil acidification alters root morphology, increases root biomass but reduces root decomposition in an alpine grassland. Environ. Pollut. 265, 115016 (2020).

Pan, S. et al. Nitrogen-induced acidification, not N-nutrient, dominates suppressive N effects on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 6568–6580 (2020).

Wei, Y. et al. Does pH matter for ecosystem multifunctionality? An empirical test in a semi-arid grassland on the Loess Plateau. Funct. Ecol. 36, 1739–1753 (2022).

Tourna, M., Freitag, T. E., Nicol, G. W. & Prosser, J. I. Growth, activity and temperature responses of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in soil microcosms. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 1357–1364 (2008).

Rotthauwe, J. H., Witzel, K. P. & Liesack, W. The ammonia monooxygenase structural gene amoA as a functional marker: molecular fine-scale analysis of natural ammonia-oxidizing populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 4704–4712 (1997).

Henry, S. et al. Quantification of denitrifying bacteria in soils by nirK gene targeted real-time PCR. J. Microbiol. Meth. 59, 327–335 (2004).

Kandeler, E., Deiglmayr, K., Tscherko, D., Bru, D. & Philippot, L. Abundance of narG, nirS, nirK, and nosZ genes of denitrifying bacteria during primary successions of a glacier foreland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5957–5962 (2006).

Henry, S., Bru, D., Stres, B., Hallet, S. & Philippot, L. Quantitative detection of the nosZ gene, encoding nitrous oxide reductase, and comparison of the abundances of 16S rRNA, narG, nirK, and nosZ genes in soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5181–5189 (2006).

Butterbach-Bahl, K., Baggs, E. M., Dannenmann, M., Kiese, R. & Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S. Nitrous oxide emissions from soils: how well do we understand the processes and their controls? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London, Ser. B 368, 20130122 (2013).

Smith, M. S. & Tiedje, J. M. Phases of denitrification following oxygen depletion in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 11, 261–267 (1979).

Burnham, K. P. & Anderson, D. R. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-theoretic Approach. (Springer, New York, 2002).

Berdugo, M. et al. Global ecosystem thresholds driven by aridity. Science 367, 787–790 (2020).

Barton, K. MuMIn: Multi-Model Inference. R Package Version 1.42.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn (2018).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing https://www.R-project.org/ (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2021).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the staff at the three experimental sites for maintaining the long-term field experiments. We also thank Dima Chen, Guozhen Du, Hui Guo, Jiuxin Guo, Zhen Li, ** Luo, Fanglong Su, Fuwei Wang, Peng Wang, Yanan Wei, Xuebin Yan, Qilai Yang, Hao Zhang, Juanjuan Zhang, Qingzhou Zhao and **anhui Zhou for assistance with field acid addition treatments. This research was partially supported by Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) [Grant Nos. 32001140 (Y.Q.), 32371626 (Y.Q.) and 32171553 (Yi Z.)], China Postdoctoral Science Foundation [Grant No. 2022T150325 (Y.Q.)], and USDA-National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) [Grant No. 2018-51106−28773 (S.H.)].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H., Y.Q., and Yi.Z. conceived the research and designed the study. Y.Q. conducted the meta-analyses. Yi Z., Y.Q., and S.H. conceived the conceptual diagram. Y.Q., X.X., K.Z., X.S., T.B., Yi W., Yi Z., Y.W., and Y.B. maintained the three field experiments. Y.Q., X.X., Yi.Z., K.Z., Yf.Z., Ye. Z., H.W., and T.H. conducted the experiments and performed the lab analyses. Y.Q., K.Z., Yi Z., S.H., and H.C. performed the data analyses. Y.Q. and S.H. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. S.B., C.J.G., L.G., H.S., C.Y., A.W., J.G., L.C., Y.Z., S.H., and M.K.F. reviewed and edited the draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks **aojun Zhang and Shu Kee Lam for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiu, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhang, K. et al. Intermediate soil acidification induces highest nitrous oxide emissions. Nat Commun 15, 2695 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46931-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46931-3

- Springer Nature Limited