Abstract

An efficient and cost-effective oxygen evolution reaction (OER) electrocatalyst is key for electrochemical energy generation and storage technologies. Here, the rational design and in situ formation of an antiperovskite-based hybrid with a porous conductive Cu1−xNNi3−y (x and y represent defect) core and amorphous FeNiCu (oxy)hydroxide shell is reported as a promising water oxidation electrocatalyst, showing outstanding performance. Benefiting from the unique advantage of core–shell structure, as well as the synergistic effect of Fe, Ni, and Cu and the highly porous hierarchical structure, the hybrid catalyst exhibits highly efficient and robust OER performance in alkaline environments, outperforming the benchmark IrO2 catalyst in several aspects. Our findings demonstrate the application potential of antiperovskite-based materials in the field of electrocatalysis, which may inspire insights into the development of novel materials for energy generation and storage applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oxygen-evolution reaction (OER) electrocatalysts play significant roles in various energy generation and storage processes. The reaction involves a multistep electron transfer process and has intrinsically sluggish kinetics, thus requiring a catalyst for promotion1,6,7,8. However, perovskite oxide-based electrocatalysts have three main drawbacks: large initial overpotential for driving OERs, poor mass activity resulting from the low specific surface area, and poor conductivity at room temperature. Compared with perovskite oxides, transition-metal (sub)nitrides (such as Ni3N9, Co4N10, and Ta5N611) have been reported to show high electrical conductivity and more favorable activities for oxygen evolution. Owing to these facts, novel OER catalysts featuring the great structural flexibility of perovskite oxides, as well as the superior conductivity of transition-metal (sub)nitrides are highly expected.

Interestingly, transitional metal elements and nitrogen/carbon can form an antiperovskite structure at a proper element ratio (AXM3; A=Cu, Al, Zn, etc.; X=N or C; M=Ni, Fe, Co, etc.), in which the position of the cations and anions is converted with respect to the conventional perovskite oxides. Due to the high flexibility in elemental composition of perovskite, antiperovskites can also be well tailored to demonstrate versatile properties. Actually, antiperovskites have gained wide attention because of their simple structure and diverse physical properties, including their superconductivity, giant magneto resistance, temperature-invariant resistance and Li-cathode materials12,13,14,15. Among the various antiperovskite compounds, antiperovskite nitrides ANM3 are a very important branch. Experimentally, Ni-based nitride ANNi3 (A=Cu and Zn) shows remarkable superconductivity16. Theoretically, density functional theory (DFT) calculations reveal that the density of states (DOS) of ANNi3 (A=Zn and Cu) is continuous near the Fermi level, suggesting their intrinsically metallic characterization17. This is significantly different from perovskite oxides, which are typically insulators at room temperature. Although combining the advantages of perovskite structure and superior conductivity, antiperovskite ANNi3 has rarely been employed in the field of electrocatalysis.

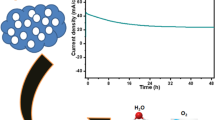

Here, we propose an antiperovskite-based porous Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu (oxy)hydroxide core–shell structured hybrid (denoted as p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu, with x and y representing defect) as a high-performance OER electrocatalyst demonstrating excellent activity and durability. A methodology based on the in situ interfacial reaction between CuNNi3 and Fe3+ for the formation of this core–shell-structured hybrid has been developed, which also leads to the in situ-formed amorphous FeNiCu shell, as well as the formation of the porous architecture. The hybrid exhibits enhanced activity and robust stability compared with the benchmark IrO2 electrocatalysts in several aspects.

Results

Catalyst synthesis and characterizations

The fabrication procedure of the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu hybrid is schematically illustrated in Fig. 1. First, polycrystalline CuNNi3 was synthesized from a mixture of copper (Cu) and nickel (Ni) powders through solid–gas reactions. Notably, excessive Cu was intentionally introduced to serve as a sacrificial template for the creation of rich pores in the final hybrid during the following etching process. The as-obtained Cu-excess CuNiN3 (denoted as CuNNi3+Cu) was then immersed in an FeCl3·6H2O aqueous solution and kept for 30 min under room temperature. During this process, copper nanoparticles were dissolved according to chemical reaction (1)18. Simultaneously, metal-state Cu and Ni in the antiperovskite structure were partially etched by Fe3+ (reaction (1) and (2)). Both contributed to the introduction of pores in the antiperovskite phase. Significantly, Fe3+, Ni2+, and Cu2+ ions were hydrolyzed to form an FeNiCu (oxy)hydroxide colloid and H+ (reaction (3))19,20. Due to the consumption of H+ by the dissolution of the antiperovskite, the hydrolysis was promoted. As a result, the precipitated FeNiCu was deposited on the surface of the antiperovskite phase, leading to the formation of a p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu core–shell hybrid.

To reveal the structure and composition of the various samples, X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurement was first carried out. As shown in Fig. 2a, the CuNNi3+Cu sample displayed three peaks at 2-theta = 43.1°, 50.2°, and 73.9°, which are corresponded to the metallic Cu phase. The remaining strong diffraction peaks indexed well with a cubic antiperovskite cell17. Rietveld refinement confirms the cubic structure (space group: pm3̅m) with a lattice constant of a = b = c = 3.741(5) Å (Supplementary Fig. 1a, Supplementary Table 1), which agrees well with that (3.745 Å) predicted by first-principle calculations16. The corresponding antiperovskite crystal structure of CuNNi3 is shown in the inset of Fig. 2a. After etching by Fe3+ for 30 min, the three peaks assigned to the metallic Cu were not observed, suggesting that the metallic Cu redundant was successfully dissolved. The new diffraction pattern still overlapped satisfactorily with that of the cubic antiperovskite phase (Rietveld refinement in Supplementary Fig. 1b; Supplementary Table 1), but with a reduction in peak intensity and slightly negative peak shift compared with the CuNNi3+Cu sample. It is assumed that the FeCl3 aqueous solution not only etched the excess metallic Cu but also influenced the antiperovskite. No additional peaks assigned to Fe-related phases were observed. To gain more information about the nature of the Fe3+-treated antiperovskite, the samples were then characterized using Raman spectroscopy. Compared with the CuNNi3+Cu sample, three additional Raman bands (Fig. 2b) located at 213 cm−1, 278 cm−1, and 556 cm−1 appeared, which are derived from asymmetric stretching of the metal and (oxy)hydroxide groups20,6,8. The representative TEM image with close observation (Supplementary Fig. 7a and b) shows a continuously smooth surface of the antiperovskite and the HRTEM image in Supplementary Fig. 7c gives lattice spacings of 0.264 nm and 0.210 nm corresponding to the (110) and (111) interplanar spacings of CuNNi3 and Cu, respectively. In addition, the energy disperse spectrum (EDS) elemental map** (Supplementary Fig. 7d) further confirms that the elements of Cu, Ni, and N were homogeneously distributed in the selected field. Applying Fe3+ treatment to the Cu-excess CuNNi3 sample caused a large change in the morphology. The p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu showed a loose nature (Supplementary Fig. 8). TEM investigations (Fig. 3a) further revealed that thin nanoflakes were decorated on the initially smooth surface of the antiperovskite, demonstrating a typical core–shell structure. The EDS spectra obtained from core and shell confirmed that the elements of the shell layer consist of Fe, Ni, and Cu (Supplementary Fig. 9). Close observation, shown in Fig. 3b, displays a distinguished Cu1−xNNi3−y–FeNiCu interface (as indicated by a white dashed line). The HRTEM image (Fig. 3c) of the FeNiCu shell and the associated fast Fourier transform (FFT) pattern of the image (Fig. 3d) are characteristic of an amorphous phase. Conversely, the lattice spacing of the Cu1−xNNi3−y core in the HRTEM image (Fig. 3e) was determined to be 0.268 nm and 0.221 nm, which corresponds to the (110) and (111) planes of cubic CuNNi3, respectively, and the FFT pattern (Fig. 3f) with bright spots depicts the polycrystalline nature of CuNNi3. EDS line-scan spectra and elemental map** analysis further identify the quintessential core–shell structure. As shown in Fig. 3g, Fe possesses strong signals in the shell region, and from Fig. 3h, Fe was located across the entire area with strong signals at the edges.

Morphology and texture characterization. a TEM and b magnified TEM images of p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu. c HRTEM and d the corresponding FFT images of the FeNiCu shell. e HRTEM and f the corresponding FFT images of the Cu1−xNNi3−y core. g Line-scan EDS spectra and h STEM-EDS element map** images of the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu. Scale bar in a is 100 nm, in b is 50 nm, in c is 10 nm, in d is 5 nm−1, in e is 5 nm, in f is 5 nm−1, in g is 200 nm and in h is 100 nm

To analyze the surface chemical valences of the samples before and after Fe3+ treatment, Fig. 4 compares the XPS spectra of the CuNNi3+Cu sample and the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu hybrid in the Cu 2p3/2 and Ni 2p regions. For the CuNNi3+Cu sample, two contributions of Cu are observed at 934.1 and 932.2 eV (Fig. 4a). The higher binding energy (BE) peak can be indexed to Cu2+, accompanied by the characteristic shakeup satellite peaks (941.9 eV and 943.7 eV). The lower BE peak indicates the presence of Cu0 or Cu+ species25,28. Because Cu0 and Cu+ cannot be differentiated in Cu 2p3/2 spectra, Auger Cu LMM spectra (Supplementary Fig. 10) were used to verify the presence of metallic Cu0 at a BE of ~568.3 eV28. After Fe3+ treatment, the intensity of the Cu2+ and satellite peaks in the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu hybrid is significantly enhanced. Figure 4b shows the core-level lines of Ni. Two distinct peaks at 869.7 eV (2p1/2) and 852.5 eV (2p3/2) of the CuNNi3+Cu emerged as the metallic state of Ni. The other two peaks centered at 873.7 eV and 855.4 eV are characteristic of Ni2+ 2p1/2 and Ni2+ 2p3/2, respectively, accompanied by two satellite peaks29,30. Similar to the intensity of Cu, after Fe3+ treatment, the intensity of divalent Ni significantly increased in p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu. Along with the results of Fig. 2d, the surface of the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu hybrid consists primarily of Fe3+, Ni2+, and Cu2+.

Electrochemical performance

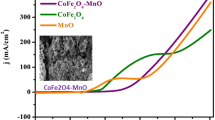

The performance of the as-obtained p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu hybrid as an electrocatalyst toward OER was assessed in 1 M KOH solution adopting a three-electrode configuration. The catalyst mass loading was controlled 0.367 mg cm−2. Similar measurements were performed on CuNNi3+Cu, CuNNi3, Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu and commercial IrO2 for direct comparison. All potentials reported were referenced to reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE). The typical polarization curves (after ohmic resistance corrections) of the five electrodes are displayed in Fig. 5a. The IrO2 catalyst demonstrated highly active OER performance with the lowest onset potential of 1.43 V and an overpotential of only 260 mV to reach 10 mA cm−2 (η10), which is consistent with the earlier reports31. The CuNNi3 catalyst exhibited lower onset potential (1.58 V) and a smaller η10 value (480 mV) compared to those of the Cu-excess CuNNi3 sample (CuNNi3+Cu, onset potential of 1.60 V, η10 = 510 mV), indicating that excessive Cu in the CuNNi3+Cu sample was less active than the antiperovskite towards the OER. However, after Fe3+ treatment, the Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu electrode had a dramatically decreased onset potential of 1.46 V and a reduced overpotential of 300 mV at 10 mA cm−2. Furthermore, when p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu with an enlarged surface area was used as the OER electrode, the catalytic activity was further enhanced. It needed an overpotential of only 280 mV to drive 10 mA cm−2, and the catalytic current largely exceeded that of the benchmark IrO2 in the high overpotential region (above 330 mV). Compared with other low-cost OER catalysts, the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu hybrid exhibits competitive catalytic performance (Supplementary Table 4). Figure 5b plots the mass activity (normalized to the mass loading) and specific activity (normalized to the surface area from BET measurements1,32 (Supplementary Fig. 11, Supplementary Table 2)) of the various electrocatalysts at η = 400 mV (1.63 V vs RHE). The p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu electrocatalyst exhibited a mass activity of 258.3 Ag−1, which is ~2.2 and 1.5 times that of the Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu and IrO2 electrocatalysts, respectively. The specific activity is well known to reflect the intrinsic activity of a catalyst for the OER6,7. From Fig. 5b, the intrinsic OER activity of catalysts followed the order of CuNNi3+Cu<IrO2<CuNNi3<Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu<p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu, indicating the attractive intrinsic activity of antiperovskite and again suggesting the highest OER activity for the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu electrocatalyst.

Electrochemical properties of catalysts. a Ohmic resistance-corrected OER activity curves of the IrO2, CuNNi3+Cu, p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu, CuNNi3 and Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu catalysts in 1 M KOH at 5 mV s−1. b Mass activities and BET surface area-normalized intrinsic activities of catalysts at η = 400 mV derived from a. c Tafel plots obtained from the steady-state measurements. d Chronopotentiometric curves of p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu and commercial IrO2 at 10 mA cm−2disk

Tafel plots were derived from polarization curves to gain the kinetic parameters of the electrodes. As drawn in Fig. 5c, the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu electrocatalyst had a Tafel slope of ~52 mV dec−1, which is close to that of IrO2 (45 mV dec−1) but much smaller than other catalysts (76–163 mV dec−1), indicating that the rate-determining step of the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu electrocatalyst occurs near the end of the multiple-electron transfer reaction, which is commonly a sign of an efficient electrocatalyst33. Further, we compared the electrochemical surface area (ECSA) of each catalyst, which was obtained from the double-layer capacitance (Cdl) (Supplementary Fig. 12). It was found that the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu catalyst exhibited the largest Cdl (10.5 mF cm−2) among all four samples, demonstrating the highest electrochemically active surface area29,30,31. The polarization curves of the catalysts normalized by ECSA are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 13. Obviously, the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu still showed the best OER activity among the catalysts. In addition, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were performed to demonstrate the significant electrode kinetic of the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu. Nyquist plots were depicted in Supplementary Fig. 14 for the CuNNi3+Cu, CuNNi3, Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu and p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu electrodes. The p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu catalyst had a much lower charge–transfer resistance (Rct) value, corresponding to a rate of reaction that was faster than those of the other samples8.

Long-term stability is another important criterion for a good OER catalyst. Figure 5d shows the chronopotentiometric curves for p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu and IrO2 at a fixed current density of 10 mA cm−2. Apparently, the potential from the IrO2 catalyst increased gradually resulting from the formation of a soluble complex anion IrO42− in alkaline environments33. In contrast, the potential from p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu almost remained unchanged throughout the entire 24-h test, indicating a high stability of the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu catalyst.

Discussion

The unique advantage of core–shell structure of the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu hybrid plays a vital role in enhancing the catalytic performance. The metallic antiperovskite core contributes high electrical conductivity, which enhances the facile electron transfer during the catalytic process. The metal (oxy)hydroxide shell is formed on surface of the metallic core, which makes the shell the active catalyst. The two components contribute synergistically during the OER process. Besides, the interaction of Fe, Ni, and Cu in the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu needs to be verified. It is well known that the do** Fe in Ni-based catalysts can enhance the catalytic activity34,35,36. According to the aforementioned Tafel slope analysis, the Tafel slope is crucially affected by Fe3+. This result strongly supports the conclusion that do** Fe into NiCu based materials can adjust the catalytic property by tuning the intrinsic kinetics37,38. To determine the role of Cu, cyclic voltammograms of p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu and Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu electrodes were recorded (Supplementary Fig. 15). ICP-OES results (Supplementary Table 3) revealed that the two samples have similar Fe content, while the content of Cu in the shell layer of p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu is higher than that of Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu. Obviously, the Ni2+/Ni3+ oxidation peak of the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu shifted to a negative potential relative to that for the Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu, suggesting that the electrochemical oxidation of Ni2+ to Ni3+ is facilitated by the larger concentration of Cu39. From the above results, the high catalytic activity p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu is also derived from the synergistic effect of Fe, Ni and Cu. Finally, the highly porous structure provided large amounts of available active sites, thus further enhancing the catalytic performance.

Ex situ XPS measurements were conducted to investigate the compositional change of p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu before and after the OER electrolysis. The divalent Cu peak in the Cu 2p3/2 spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 16a) slightly increased in intensity after the OER. For the Ni 2p spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 16b), the formation of NiIII is in accordance with previous reports6. First, stoichiometric Ba(NO3)2, Sr(NO3)2, Co(NO3)2·6H2O, and Fe(NO3)3·9H2O were added to the deionized water and dissolved under vigorous stirring. Then ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (C10H16N2O8, EDTA) and citric acid (C6H8O7, CA) were introduced as complexing agents to the above solution and the molar ratio of EDTA: CA: metal ions was 1:2:1. In order to promote the complexation process, an ammonium solution was added to adjust the pH of the solution to about 6. The mixture was under vigorous stirring at 90 °C to allow the water to evaporate and yield a gel. The above transparent gel was transferred to a crucible and pre-treated at 250 °C for 5 h to obtain a solid precursor. The BSCF was finally obtained after subsequently calcinated at 1000 °C for 10 h in air. The Fe3+-BSCF was prepared from BSCF under the same condition as that of the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu.

Synthesis of bulk SrTi0.1Fe0.85Ni0.05O3−δ (STFN) and Fe3+-STFN

The perovskite SrTi0.1Fe0.85Ni0.05O3−δ was produced through the similar synthesis route with BSCF except that the final calcination was conducted at 1000 °C and held for 5 h. The Fe3+-STFN was prepared from STFN under the same condition as that of the p-Cu1−xNNi3−y/FeNiCu.

Materials characterization

RT powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) was performed on the Rigaku Smartlab equipped with Cu kα radiation. The scanning was set in the 2θ range from 10° to 90° with intervals of 0.02°. Rietveld refinement of the XRD patterns was conducted to get more detailed structural information of the samples using the GSAS-EXPGUI package. Raman spectra were recorded using a micro-Raman spectrometer (HR800 UV). The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were collected from 4000 to 500 cm−1 using a spectrophotometer (Nexus 870). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were performed on PHI550 and the data were fitted by XPSPEAK41. The specific surface areas were characterized through nitrogen adsorption-desorption measurements (BELSORP II) using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method. The corresponding pore size distributions were estimated according to the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) method. Approximately 2.0 g of the samples were pretreated under 200 °C for at least 3 h before N2 physisorption measurements at 77 K. Field-emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) images were acquired on a HITACHI S-4800, transmission electron microscope (TEM) and high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM) images were collected from JEOL JEM-200CX.

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical performance was assessed on a Bio-Logic SP-300 workstation at RT. All tests were carried out in 1 M potassium hydroxide (KOH) electrolyte in a conventional three-electrode configuration. Reference electrode: Ag/AgCl electrode. Counter electrode: platinum wire. Working electrode: catalyst-modified glassy carbon (GC). The catalyst ink contained 10 mg of the measured catalyst, 10 mg of conductive carbon (Super P Li) and 100 μL of 5 wt% Nafion solution ultrasonically dispersed in 1 mL of the absolute ethanol. In total 10-μL of the homogeneous dispersion was transferred onto the surface of the GC substrate (0.2475 cm2) and dried at RT. The catalyst mass loading was ~0.367 mg cm–2disk.

All the potentials reported were referenced vs reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) according to the equation with IR compensation: E(Ag/AgCl)+1.002 V = E(RHE). The overpotential (η) was obtained based on the equation: E(RHE)−1.23 V = η (V). The electrolyte was purged with O2 for 30 min before each measurement. Polarization curves were recorded using linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) under a rotation rate of 1600 r.p.m. The potential window ranged from 0 to 0.8 V (vs Ag/AgCl) and the scanning rate was 5 mV s−1. Cyclic voltammograms (CVs) tests were carried out in the potential window of 0.07–0.17 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) with different swee** rates from 20 to 100 mV s−1 to calculate the electrochemical double-layer capacitances (EDLCs), Cdl. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were carried out in the frequency range of 105 to 0.1 Hz at 0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl. The a.c. voltage was set at 5 mV. Durability was evaluated by chronopotentiometry test performed under constant current density of 10 mA cm−2disk with a rotation rate of 1600 r.p.m.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Suntivich, J., May, K. J., Gasteiger, H. A., Goodenough, J. B. & Shao-Horn, Y. A perovskite oxide optimized for oxygen evolution catalysis from molecular orbital principles. Science 334, 1383–1385 (2011).

Zhang, J. T., Zhao, Z. H., **a, Z. H. & Dai, L. M. A metal-free bifunctional electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution reactions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 444–452 (2015).

Ma, T. Y., Dai, S., Jaroniec, M. & Qiao, S. Z. Metal-organic framework derived hybrid Co3O4-carbon porous nanowire arrays as reversible oxygen evolution electrodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 13925–13931 (2014).

Hunter, B. M., Gray, H. B. & Müller, A. M. Earth-abundant heterogeneous water oxidation catalysts. Chem. Rev. 116, 1420–14136 (2016).

Grimaud, A. et al. Double perovskites as a family of highly active catalysts for oxygen evolution in alkaline solution. Nat. Commun. 4, 2439 (2013).

Xu, X. M. et al. Co-do** strategy for develo** perovskite oxides as highly efficient electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Sci. 3, 150018 (2016).

Chen, G. et al. Two orders of magnitude enhancement in oxygen evolution reactivity on amorphous Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3−d nanofilms with tunable oxidation state. Sci. Adv. 3, e1603206 (2017).

Zhao, B. T. et al. A tailored double perovskite nanofiber catalyst enables ultrafast oxygen evolution. Nat. Commun. 8, 14586 (2016).

Xu, K. et al. Metallic nickel nitride nanosheets realizing enhanced electrochemical water oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4119–4125 (2015).

Zhang, Y. Q. et al. Rapid synthesis of cobalt nitride nanowires: highly efficient and low-cost catalysts for oxygen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 8670–8674 (2016).

Wang, L., Zhou, X. M., Nguyen, N. T., Hwang, I. & Schmuki, P. Strongly enhanced water splitting performance of Ta3N5 nanotube photoanodes with subnitrides. Adv. Mater. 28, 2432–2438 (2016).

Kamishima, K. et al. Giant magnetoresistance in the intermetallic compound Mn3GaC. Phys. Rev. B 63, 024426 (2000).

He, T. et al. Superconductivity in the non-oxide perovskite MgCNi3. Nature 411, 54 (2011).

Chi, E. O., Kim, W. S. & Hur, N. H. Nearly zero temperature coefficient of resistivity in antiperovskite compound CuNMn3. Solid State Commun. 120, 307–310 (2001).

Lai, K. T., Antonyshyn, I., Prots, Y. & Valldor, M. Anti-perovskite Li-battery cathode materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 9645–9649 (2017).

He, B. et al. CuNNi3: a new nitride superconductor with antiperovskite structure. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 26, 125015 (2013).

Helal, M. A. & Islam, A. K. M. A. Elastic, electronic, and optical properties of hypothetical SnNNi3 and CuNNi3 in comparison with superconducting ZnNNi3. Physica B 406, 4564–4568 (2011).

Zhu, Y. P. et al. Enhancing electrocatalytic activity for hydrogen evolution by strongly coupled molybdenum nitride@nitrogen-doped carbon porous nano-octahedrons. ACS Catal. 7, 3540–3547 (2017).

Zhang, Y. Q. et al. Ultrathin CNTs@FeOOH nanoflake core/shell networks as efficient electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. Mater. Chem. Front. 1, 709–715 (2017).

Wang, L., Nguyen, N. T., Zhang, Y. J., Bi, Y. P. & Schmuki, P. Enhanced solar water splitting by swift charge separation in Au/FeOOH sandwiched single crystalline Fe2O3 nanoflake photoelectrodes. ChemSusChem 10, 2720–2727 (2017).

Liu, J. Q., Zheng, M. B., Shi, X. Q., Zeng, H. B. & **a, H. Amorphous FeOOH quantum dots assembled mesoporous film anchored on graphene nanosheets with superior electrochemical performance for supercapacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 919–930 (2016).

Desilvestro, J., Corrigan, D. A. & Weaver, M. J. Characterization of redox states of nickel hydroxide film electrodes by in situ surface Raman spectroscopy. J. Electrochem. Soc. 135, 885–892 (1988).

Wu, Y. Z. et al. Fast and simple preparation of iron-based thin films as highly efficient water-oxidation catalysts in neutral aqueous solution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 4870–4875 (2015).

Grosvenor, A. P., Kobe, B. A., Biesinger, M. C. & Mclntyre, N. S. Investigation of multiplet splitting of Fe 2p XPS spectra and bonding in iron compounds. Surf. Interface Anal. 36, 1564–1574 (2004).

Ma, Y. M. et al. Galvanic-replacement mediated synthesis of copper-nickel nitrides as electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 24850–24858 (2017).

Zhu, Y. P. et al. A hierarchical Zn2Mo3O8 nanodots-porous carbon composite as a superior anode for lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Commun. 52, 9402–9405 (2016).

Zhu, Y. P., Chen, G., Zhong, Y. J., Zhou, W. & Shao, Z. P. Rationally designed hierarchically structured tungsten nitride and nitrogen-rich graphene-like carbon nanocomposite as efficient hydrogen evolution electrocatalyst. Adv. Sci. 5, 1700603 (2017).

Liu, P. & Hensen, E. J. M. Highly efficient and robust Au/MgCuCr2O4 catalyst for gas-phase oxidation of ethanol to acetaldehyde. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 14032–14035 (2013).

Zhang, B. et al. Iron-nickel nitride nanostructures in situ grown on surface-redox etching nickel foam: efficient and ultrasustainable electrocatalysts for overall water splitting. Chem. Mater. 28, 6934–6941 (2016).

Jia, X. D. et al. Ni3FeN nanoparticles derived from ultrathin NiFe-layered double hydroxide nanosheets: an efficient overall water splitting electrocatalyst. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1502585 (2016).

Feng, J. X. et al. Design and synthesis of FeOOH/CeO2 heterolayered nanotube electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 28, 4698–4703 (2016).

Suntivich, J., Gasteiger, H. A., Yabuuchi, N. & Shao-Horn, Y. Electrocatalytic measurement methodology of oxide catalysts using a thin-film rotating disk electrode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, B1263–B1268 (2010).

Suen, N. T. et al. Electrocatalysis for the oxygen evolution reaction: recent development and future perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 337–365 (2017).

Trotochaud, L., Young, S. L., Ranney, J. K. & Boettcher, S. W. Nickel-iron oxyhydroxide oxygen-evolution electrocatalysts: the role of intentional and incidental iron incorporation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 6744–6753 (2014).

Long, X. et al. A strongly coupled graphene and FeNi double hydroxide hybrid as an excellent electrocatalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 126, 7714–7718 (2014).

Liu, J. L. et al. Free-standing single-crystalline NiFe-hydroxide nanoflake arrays: a self-activated and robust electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution. Chem. Commun. 54, 463–466 (2018).

Han, L., Dong, S. J. & Wang, E. K. Transition-metal (Co, Ni, and Fe)-based electrocatalysts for the water oxidation reaction. Adv. Mater. 28, 9266–9291 (2016).

Gong, M. & Dai, H. J. A mini review of NiFe-based materials as highly active oxygen evolution reaction electrocatalysts. Nano Res. 8, 23–39 (2015).

Zhang, P. L. et al. Dendritic core-shell nickel-iron-copper metal/metal oxide electrode for efficient electrocatalytic water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 9, 381 (2018).

Tang, C., Cheng, N. Y., Pu, Z. H., **ng, W. & Sun, X. P. NiSe nanowire film supported on nickel foam: an efficient and stable 3D bifunctional electrode for full water splitting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 127, 9483–9487 (2015).

Zhou, W. J. et al. Ni3S2 nanorods/Ni foam composite electrode with low overpotential for electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 2921–2924 (2013).

Xu, X., Song, F. & Hu, X. L. A nickel iron diselenide-derived efficient oxygen-evolution catalyst. Nat. Commun. 7, 12324 (2016).

Sun, H. N. et al. B-Site cation ordered double perovskites as efficient and stable electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 5722–5728 (2017).

Joya, K. S. & Groot, H. J. M. Controlled surface-assembly of nanoscale leaf-type Cu-Oxide electrocatalyst for high activity water oxidation. ACS Catal. 6, 1768–1771 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, the Changjiang Scholars Program (T2011170), the Jiangsu Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars (No. BK20170043) and the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 21576135).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y. Zhu and Z.S. designed the project. Y. Zhu, G.C., and N.M. conducted the experiments. G.C., Y. Zho., and Y.C. carried out the characterization. Y. Zhu carried out and analyzed the electrochemical measurements. W.Z. and Z.S. offered consultation. Y. Zhu, Y. Zho., W.Z., and Z.S. co-wrote the paper. Every author contributed to the discussion and revision of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Y., Chen, G., Zhong, Y. et al. A surface-modified antiperovskite as an electrocatalyst for water oxidation. Nat Commun 9, 2326 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04682-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04682-y

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Duplex Interpenetrating-Phase FeNiZn and FeNi3 Heterostructure with Low-Gibbs Free Energy Interface Coupling for Highly Efficient Overall Water Splitting

Nano-Micro Letters (2023)

-

Antiperovskite nitride Cu3N nanosheets for efficient electrochemical oxidation of methanol to formate

Science China Materials (2023)

-

Hierarchical iridium-based multimetallic alloy with double-core-shell architecture for efficient overall water splitting

Science China Materials (2020)

-

Nickel iron carbonate hydroxide hydrate decorated with CeOx for highly efficient oxygen evolution reaction

Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry (2019)