Abstract

This paper investigates conditions under which the downstream firm can benefit from cost disadvantages arose from upstream sector. We consider a vertically related industry consisting of two upstream firms (a specific input supplier and a common input supplier) and one multi-product downstream firm. The downstream firm produces two vertically differentiated products and sells either in two separate markets or in one market. Findings identify a situation under the view that both downstream firms’ profits and consumer surplus are increasing with the input production cost or the bargaining power of upstream firms, which depends on whether the common input supplier has market power. Specifically, in the one market case, we shed light on the importance of the marginal product of the common input of the high-quality product for both the downstream firm’s profit and consumer surplus improving. Moreover, we check the robustness of our findings for extension by considering horizontal product differentiation, price competition, using the specific input for two products, and bilateral bargaining. Our main findings still hold.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In 1993, Shimano’s sales were approximately 75% of global bicycle components, or about $1.7 billion. For the mountain bike market, in particular, Shimano had approximately 80% market share in 1990. For more details, please see Fixson and Park (2008).

A strand of papers also studies strategic interactions among products. For example, Ottaviano and Thisse (2011) apply a linear monopolistic competition model to discuss how the strategic interaction between oligopolistic firms affects product diversity. Arya and Mittendorf (2010) investigate a single-input multi-product firm whose product lines interact via the use of a common input. Johnson and Myatt (2003) investigate the product line strategy with multiple quality-differentiated products. Bernard et al. (2011) develop a general equilibrium of multiple-product, multiple-destination firms to examine their production and export decisions.

Kopel et al. (2017) consider a multi-input-multi-product firm that sells two different products in two independent markets and show that purchasing complementary inputs from non-integrated suppliers can be optimal for a multi-product firm. Laussel and Resende (2019) investigate the effect of asymmetric information from final demand on strategic interaction between a downstream monopolist and a set of upstream monopolists that independently produce complementary inputs. Kitamura et al. (2018) build a model of exclusive contracts in the presence of complementary inputs, requiring the final product to have multiple complementary inputs.

We focus on the effects of raising a specific input production price on the downstream firm’s profit. Therefore, we simplify the marginal cost to null for the common input.

Even if we assume the market structure for the common input is an oligopoly, then as long as the common input suppliers have market powers to decide the input prices, our results still hold.

From the inverse demand functions, \({p}_{1}=(1-{x}_{1})\) and \({p}_{2}=q(1-{x}_{2})\), which show that the quality differentiation q also appears as the market size difference. As the prices of inputs are given, the two products are independent in the separated market. However, the two markets interact each other through the derived demand of common input. Therefore, q plays the important role, and we still call the two products vertically differentiated.

The disagreement payoff of supplier A is zero since it has no alternative trading partner for simplification. The result still holds if the disagreement point of supplier A is some positive real number.

For more details, please refer to Appendix A.

To ensure a positive output of product 1, we can derive a ceiling of marginal cost c for input A, which is \(c<{c}_{1}=\frac{q{(\beta -1)}^{2}+\left(2-q\right)+q\beta }{q{\beta }^{2}+2}\). Using \(c<{c}_{1}\), we can ensure \(\frac{\partial {w}_{A}^{*}}{\partial \phi }>0\) and \(\frac{\partial {w}_{B}^{*}}{\partial \phi }<0\).

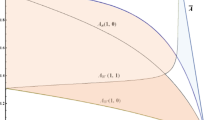

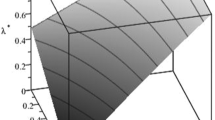

Using the condition for ensuring positive output of product 1, we can derive \(\left(\frac{{d}^{2}{\pi }^{D}}{d{\phi }^{2}}\right)={A}_{2}\left(1-\mathrm{c}\right)\left(q{\beta }^{2}+4\right)+2q\beta >0\) due to \({A}_{2}>0\). It implies that there is a U-shape relationship between bargaining power and the downstream firm’s profitability.

For more details, please refer to Appendix B.

Substituting \({x}_{1}\) and \({x}_{2}\) in stage 1 into \(\frac{d({CS}_{1}+{CS}_{2})}{dc}\), we have \(\frac{d({CS}_{1}+{CS}_{2})}{dc}=\frac{(1+q{\beta }^{2})}{2[q{\beta }^{2}\left(4-\phi \right)+4]}\left[-\left(1-c\right)\left(2-\phi \right)\left(q{\beta }^{2}+4\right)+2q\beta (3-\phi )\right]\), which is similar to (A.2). It implies that \(\frac{d({CS}_{1}+{CS}_{2})}{dc}>0\) if\(\overline{c }<c<{c}_{1}\).

To ensure positive output of product 1, we can derive a ceiling of marginal cost c for input A, which is \(c<{c}_{1}=\frac{q{(\beta -1)}^{2}+\left(2-q\right)+q\beta }{q{\beta }^{2}+2}\). Using \(c<{c}_{1}\), we can ensure \(\frac{d{CS}_{2}}{d\phi }>0\) and \(\frac{d{CS}_{1}}{d\phi }<0\).

Substituting \({x}_{1}\) and \({x}_{2}\) in stage 1 into \(\frac{d({CS}_{1}+{CS}_{2})}{d\phi }\), we have \(\frac{d({CS}_{1}+{CS}_{2})}{d\phi }=\frac{\left[\left(1-c\right)\left(2+q{\beta }^{2}\right)-q\beta \right]}{{\left[q{\beta }^{2}\left(4-\phi \right)+4\right]}^{2}}\left[-\left(1-c\right)\left(2-\phi \right)\left(q{\beta }^{2}+4\right)+2q\beta (3-\phi )\right]\), which is similar to (25). It implies that \(\frac{d({CS}_{1}+{CS}_{2})}{d\phi }>0\) when \(\overline{\phi }<\phi \le 1\) if \({c}_{\phi }<c\le {c}_{1}\).

Even if the specific input supplier has full bargaining power, as long as the marginal product of the common input of product 1 is large enough, our main findings still hold.

From (15b) and (16), the reaction functions of inputs relate to the marginal product of the common input. When \(0<\beta <1\), there is strategic complementarity, but there is strategic substitution when \(\beta >1\). Moreover, the reaction function of input A is a vertical line as \(\beta =1\). We have \(({{\partial }^{2}U}_{A}/\partial {w}_{A}\partial c)=\frac{(2-\phi )}{2}>0\). It implies that an increase in the marginal cost of a specific input supplier shifts the reaction function of input A to the parallel right. The reaction function of input B is a horizontal line as \(\beta =1\). Therefore, no matter how the marginal cost of a specific input supplier changes, the price of input B does not change.

For more details, please refer to Appendix C.

For more details, please refer to Appendix C.

For more details, please refer to Appendix C.

For more details, please refer to Appendix D.

The effect of the marginal cost of the specific input supplier on the input prices is \(\frac{\partial {w}_{A}^{*}}{\partial c}=\frac{2(1+q)({\beta }_{1}^{2}q+{\beta }_{2}^{2})}{[3{\left({\beta }_{1}q+{\beta }_{2}\right)}^{2}+4q{({\beta }_{1}-{\beta }_{2})}^{2}]}>0\) and \(\frac{\partial {w}_{B}^{*}}{\partial c}=\frac{-(1+q)({\beta }_{1}q+{\beta }_{2})}{[3{\left({\beta }_{1}q+{\beta }_{2}\right)}^{2}+4q{({\beta }_{1}-{\beta }_{2})}^{2}]}<0\).

Using (24), we have \(\frac{\partial {w}_{A}^{*}}{\partial c}=\frac{\left(\frac{{-\partial }^{2}{U}_{A}}{\partial {w}_{A}\partial c}\right)\left(\frac{{{\partial }^{2}U}_{B}}{\partial {{w}_{B}}^{2}}\right)}{D}>0\) and \(\frac{\partial {w}_{B}^{*}}{\partial c}=\frac{-\left(\frac{{-\partial }^{2}{U}_{A}}{\partial {w}_{A}\partial c}\right)\left(\frac{{\partial }^{2}{U}_{B}}{\partial {w}_{B}\partial {w}_{A}}\right)}{D}<0\) due to \(\frac{{{\partial }^{2}U}_{A}}{\partial {{w}_{A}}^{2}}<0\), \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}{U}_{A}}{\partial {w}_{A}\partial {w}_{B}}<0\), \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}{U}_{B}}{\partial {w}_{B}\partial {w}_{A}}<0\), \(\frac{{{\partial }^{2}U}_{B}}{\partial {{w}_{B}}^{2}}<0\),\(\frac{{\partial }^{2}{U}_{A}}{\partial {w}_{A}\partial c}>0\), and the stability condition \(D>0\) when \({\phi }_{B}\) is large enough.

References

Arora, A., & Gambardella, A. (1990). Complementarity and external linkages: The strategies of the large firms in biotechnology. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 38, 361–379.

Arya, A., & Mittendorf, B. (2010). Input price discrimination when buyers operate in multiple markets. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 58, 846–867.

Bernard, A. B., Redding, S. J., & Schott, P. K. (2010). Multiple-product firms and product switching. American Economic Review, 100, 70–97.

Bernard, A. B., Redding, S. J., & Schott, P. K. (2011). Multiple-product firms and trade liberalization. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126, 1271–1318.

Chen, Z. (2003). Dominant retailers and the countervailing-power hypothesis. RAND Journal of Economics, 34, 612–625.

Fixson, S. K., & Park, J. K. (2008). The Power of integrality: Linkages between product architecture, innovation, and industry structure. Research Policy, 37, 1296–1316.

Johnson, J. P., & Myatt, D. P. (2003). Multiproduct quality competition: Fighting brands and product line pruning. American Economic Review, 93, 748–774.

Kimmel, S. (1992). Effects of cost changes on oligopolists’ profits. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 40, 441–449.

Kitamura, H., Matsushima, N., & Sato, M. (2018). Exclusive contracts with complementary inputs. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 56, 145–167.

Kopel, M., Loffler, C., & Pfeiffer, T. (2016). Sourcing strategies of a multi-input-multi-product firm. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 127, 30–45.

Kopel, M., Loffler, C., & Pfeiffer, T. (2017). Complementary monopolies and multi-product firms. Economics Letters, 157, 28–30.

Laussel, D., & Resende, J. (2019). Complementary monopolies with asymmetric information. Economic Theory. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00199-019-01197-5

Manova, K., & Yu, Z. (2017). Multi-product firms and product quality. Journal of International Economics, 109, 116–137.

Ottaviano, G. I., & Thisse, J. F. (2011). Monopolistic competition, multiproduct firms and product diversity. The Manchester School, 79, 938–951.

Wang, X. H., & Zhao, J. (2010). Why are firms sometimes unwilling to reduce costs? Journal of Economics, 101, 103–124.

Yoshida, S. (2018). Bargaining power and firm profits in asymmetric duopoly: An inverted-U relationship. Journal of Economics, 124, 1–20.

Zhao, J. (2001). A characterization for the negative welfare effects of cost reduction in cournot oligopoly. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 19, 455–469.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We are grateful to seminar participants at NTU Trade Workshop for their valuable comments, leading to substantial improvements of this paper. The usual disclaimer applies.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Shih, PC., Lin, YS. & Lin, YJ. Input price, bargaining power, and a multi-input-multi-product firm. JER 75, 69–92 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42973-022-00117-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42973-022-00117-y