Abstract

The **g-Wei Floodplain, located in Shaanxi, China, has been home to various groups of people over the last 5000 years. Drawing together evidence from archaeology, paleobotany, geomorphology, climate sciences, and history, this paper provides a longue durée study of the local (pre)history of human occupation in this area with a special focus on human adaptation strategies and environmental history. In particular, the study summarizes and evaluates archaeological and geomorphological field research conducted over the last ten years and connects it with often overlooked local historical accounts and recent climate research in the Wei River Valley and observations on recent economic developments and their impact on both the environment and the people living in it. In spite of a rather long hiatus in occupation from the second century BCE to the twelfth century CE, the evidence shows that there are close similarities in human-environment relations and even continuities into the modern period. Though being a highly localized study, this paper can serve as an example for how such longue durée studies may be conducted in other regions, and it provides some suggestions for future field and laboratory research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper addresses the environmental history and human adaptation strategies of a local community in Shaanxi 陕西, China, over the past 5000 years. This small-scale, nuanced study is meant to shed some light on the relationship between humans and their environment in this location but also provide an example for longue durée studies in other locations and some suggestions for future field and laboratory research.

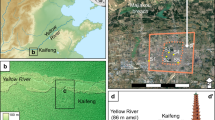

This paper focuses in particular on the **g 泾 Wei 渭 floodplain around the archaeological site of Yangguanzhai 杨官寨 (YGZ), a large mid- to late Yangshao 仰韶 period (3500–3000 cal. BCE) village located in the central Wei River Valley on the first terrace of the **g River. The **g is the largest tributary of the Wei River and flows in from the north. More than ten years of fieldwork have revealed hundreds of features covering an area close to one square kilometer (Fig. 1). Located near one of China’s largest and most active river systems, the site was greatly affected by its immediate environment. Over the last ten years, about 20,000 square meters of excavation area have been exposed at YGZ, allowing some insights into the site structure, its history, and relationship with other Yangshao sites in the Wei River Valley (Shaanxi 2009; Shaanxi sheng 2009; Shaanxi sheng and Baishui xian 2018) (Fig. 3).

2.1 Neolithic cemetery

The Neolithic cemetery contained only single burials. Tomb sizes varied little, the graves usually being just large enough to hold the body. Based on the preliminary archaeological report of the cemetery published so far, only 3% of the excavated tombs (11 out of 343) contained ceramic vessels, usually only one or two ceramic vessels each, including cups, jars, or basins (Shaanxi sheng 2018a). Only one tomb held an amphora, laid next to the body. A few tomb occupants had personal ornaments such as bone hairpins, beads, bracelet, or pendants. If differences in tomb size and tomb furnishing are an indicator of social hierarchy, then the YGZ cemetery suggests a society established on egalitarian principles with no differentiation by age, sex, or social status, at least in death.

2.2 Settlement layout

In size, the area within the ditch at YGZ is about twenty times larger than any of the earlier Neolithic sites in the Wei River Valley, such as Banpo (Zhongguo Full size image

As mentioned above, hui keng 灰坑, literally “ash pits,” generally interpreted as garbage dumps, account for over 80% of the features excavated at YGZ and other places in the Wei River Valley such as Quanhucun mentioned above. These pits have generally attracted little interest as objects of research; however, their history can be complex as they may have gone through several incarnations of usage such as dwellings or storage pits before having served as dumps and then closed after having been filled with trash. So far, only one such pit, H85, has been excavated and researched in great detail, and we will discuss it further below due to its complex history (Shaanxi sheng and Zhong Mei 2018).

In addition to over 49 houses, 896 so-called ash pits, 9 ditches, and 32 urn burials, a total of 26 kilns were found in Beiqu and Nanqu.Footnote 2 Several kilns were dug into the banks of the ditch. In several places, there are layers of pottery sherds in the ditch, as for instance recorded near the “West Gate” of the trenched area. Many of these sherds are restorable (Shaanxi 2009; Wang and Lee 2010). In Nanqu, a development postdating the ditched area, archaeologists found several kilns and 13 cave dwellings arrayed along an ancient cliff, many of them in alternating sequence of kilns and dwellings (Fig. 6). Some of these cave dwellings differed from other houses in the number of hearths found inside: one contained three, another two. The excavators believe that this area was devoted to pottery making and that the cave dwellings next to the kilns served as working spaces, but they do not say why more than one hearth should be needed in some of them. Among the many pits in this area, one (H402) contained a group of complete ceramic vessels, including 22 amphoras, 19 jars, 16 bowls, 9 basins, 5 urns, some unfired pottery, and one object that investigators believe to be a potter’s wheel (Fig. 7).Footnote 3

It seems that this large settlement had no “center” or “central place.” The clusters of houses scattered around the site likewise showed no indication of settlement planning. The buildings were orientated in a variety of directions, and pits were scattered everywhere in between. The anthropogenic deposits at the site consist mostly of household waste, including fragmented building materials of daub, burnt earth, residential matting or floors of animal enclosures, organic waste, and a large amount of broken or otherwise unusable ceramics (Fox 2013). Waste associated with pottery productions were found in many places, some of them deformed pottery but mostly vitrified chunks from broken kilns, and it has thus been suggested that the site may have been a ceramic production center, though further excavation work is necessary to test this hypothesis (Hein et al. forthcoming). The two well-preserved kilns found in the northeast section have intact fire boxes and fire chambers, where the walls show the provenience of the vitrified materials. Household hearths produced no vitrified materials despite repeated firing, indicating that the temperature was not high enough for vitrification.

2.3 Special-purpose buildings

The houses at YGZ were constructed with wattle and daub similar to other Neolithic dwellings in the Wei River Valley. Largely missing at YGZ are large houses of square or rectangular shape as they have been found in earlier or contemporary sites in the valley (Shaanxi sheng and Baishui xian Full size image