Highlights

-

The development history and key milestones of ovonic threshold switch (OTS) materials were comprehensively summarized. Combined with the latest advancements of OTS research, the mainstream OTS material systems were systematically introduced.

-

A thorough overview of the prevailing viewpoints regarding the OTS switching mechanisms was presented.

-

Recent progress in OTS devices for applications in 3D memory, self-selecting memory, and neuromorphic computing was summarized.

Abstract

Today’s explosion of data urgently requires memory technologies capable of storing large volumes of data in shorter time frames, a feat unattainable with Flash or DRAM. Intel Optane, commonly referred to as three-dimensional phase change memory, stands out as one of the most promising candidates. The Optane with cross-point architecture is constructed through layering a storage element and a selector known as the ovonic threshold switch (OTS). The OTS device, which employs chalcogenide film, has thereby gathered increased attention in recent years. In this paper, we begin by providing a brief introduction to the discovery process of the OTS phenomenon. Subsequently, we summarize the key electrical parameters of OTS devices and delve into recent explorations of OTS materials, which are categorized as Se-based, Te-based, and S-based material systems. Furthermore, we discuss various models for the OTS switching mechanism, including field-induced nucleation model, as well as several carrier injection models. Additionally, we review the progress and innovations in OTS mechanism research. Finally, we highlight the successful application of OTS devices in three-dimensional high-density memory and offer insights into their promising performance and extensive prospects in emerging applications, such as self-selecting memory and neuromorphic computing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

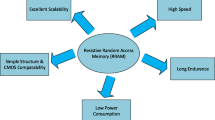

The era of big data and AIoT (Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things) necessitates the novel memory technologies for massive and quick integration of data storage, which is predicted to reach 175 ZB (1 zettabyte = 1021 byte) in 2025 [1]. The 3D stackable emerging non-volatile memory has become a key solution to address the challenge. In 3D high-density stacking, as process nodes continue to shrink from hundreds of nanometers to a few nanometers, the spacing between the parallel memory cells in the stack decreases, resulting in an increased load on the metal interconnects (Fig. 1a). “Leakage current” or “sneak current” becomes an unavoidable issue. Leakage current can cause crosstalk between neighboring memory cells, affecting read and write operation, interfering with stored data, reducing storage lifespan, and increasing power consumption [2,31, 32]. Thirdly, as the most frequent read operation in practical 3D memory needs to switch on/off the OTS selector, the endurance of the OTS device should be several orders of magnitude higher than the one of the memory unit (typically 106 cycles for PCM and resistance random access memory RRAM [20, 33]), that is, exceeding 108 cycles for the OTS cell. This necessitates OTS materials with high thermal stability (to avoid crystallization-caused failure) and no phase separation during operation. Fourthly, the amorphous state of OTS device should be able to withstand a temperature of 400–450 °C in the back-end-of-line (BEOL) process since the OTS behavior disappears upon crystallization, in which the insulator and contact metal layers are deposited [29, 34]. This requires the crystallization temperature of the amorphous OTS material to be higher than 400 °C. Fifthly, to be compatible with advanced logic applications (e.g., 3.3 V for I/O pin) and also reduce the power consumption, an OTS cell with a low Vth are recommended [35]. This implies that the material's mobility gap and trap state density should not be too large. Obviously, this requirement is contrary to that of low Ioff; therefore, a comprehensive consideration is needed. To achieve high-speed storage, the switching speed of the OTS device should be within 100 ns, faster or comparable with the memory units. This requires the OTS material to be chalcogenides without Ag, Cu, etc., active elements, avoiding atomic diffusion and maintaining an electron-dominated switching process. In addition, the drift of Vth (i.e., the change of Vth over time after the operation) in OTS materials is also a noteworthy issue; Vth drift should be as small as possible. It should be noted that the OTS device structure (such as OTS material layer thickness, multi-layer structure [36]) and operation mode [37] can also affect the overall device performance.

The development of OTS material systems is not confined to a single pathway. Specifically, the research on OTS material compositions generally exhibits a trend from simplicity to complexity. Typically, the development starts with a simple basic material with good performance, which is then analyzed and optimized to address any deficiencies. Through do** and compositional optimization, a multi-component material system is eventually established. The reasons for this development trend are multifaceted [29]. Firstly, in the research and development of OTS switch devices, optimization of specific components is often carried out for engineering considerations or the need for mechanism studies to enhance certain performance indicators. Secondly, the successful application of OTS devices in commercial products is exciting, but the process of commercialization introduces additional considerations such as cost, process compatibility, and environmental impact. These new requirements drive innovation and optimization of OTS materials. Lastly, the optimization and innovation of a material system are often propelled by the advancement of its mechanism research. Different theoretical analyses and explanations of OTS switching mechanisms lead to variations, and the optimization of performance under different theories will employ different compositional optimization methods.

Do** processes and compositional optimization, as typical means of material performance enhancement, are also applicable to OTS devices. It is evident that the introduction of a new element usually affects more than one key parameter, regardless of the initial purpose of its introduction. From a material design perspective, the incorporation of elements such as Ge, As, Si, C, N, and B can improve the material’s crystallization temperature, stabilize the amorphous system, or reduce leakage by introducing elements with wider mobility gap. Subsequently, targeted improvements can be made based on the defects in these binary compounds. The participation of these elements, with varying relative concentrations, often nonlinearly affects electrical parameters such as Vth and Ioff. Therefore, the composition of OTS materials is not a simple superposition of fixed do** elements. On the contrary, these elements interact with each other in a multi-component system, and the addition of some elements may even cause the system to lose its OTS characteristics. Although dozens of OTS materials have been explored since 1966, Se, Te, and S chalcogens are essential elements, as summarized in Fig. 4, which are discussed in detail as follows.

3.1 Se-based OTS

Selenium (Se) is the number 34 element in the periodic table (Fig. 5a), with an atomic radius of 1.20 Å. Se-based OTS materials, in which the Se element has the highest concentration, often combine with Ge to form Ge–Se alloys. Ge–Se compounds have been widely reported as OTS matrix for mechanism analysis, do**, and compositional optimization [41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. Ge–Se exhibits a high crystallization temperature, with GeSe having a crystallization temperature of 350 °C (Fig. 5b) and further rising up to 600 °C with higher Se content [38, 39]. Since elemental Se has a large mobility gap of ~ 2 eV, the Ge–Se-based materials have a mobility gap ranging from approximately 1–2 eV (Fig. 5c) [46], demonstrating < 10−7A low leakage current and > 108-cycle high endurance (Fig. 6b, h). The trap states of Ge–Se alloy are located at 0.42–0.56 eV below the conduction band edge using a Poole–Frenkel fitting [38]. The Ge–Se bond has a short bond length of ~ 2.38 Å and thereby high bond energy of 234.5 kJ mol−1 [32]. Thus, Se-based OTS materials generally exhibited large Vth, > 2 V@10 nm thick, which would further increase with higher Se concentration (Fig. 6d) [38].

Ge–Se OTS selectors. a Device structure with 50-nm plug. b Leakage current. c AC I–V curves. d Vth increase with higher Se content. e Vth and Ioff distributions. f Ion vs. leakage current. g Ioff comparison and h endurance. Adapted with permission from [38]. Copyright 2018, IEEE

When optimizing the Ge–Se system, the overall objective is to construct a stable amorphous network, enhance thermal stability, reduce leakage current, and, to some extent, lower the Vth. Researchers have extensively investigated the improvement of Ge–Se system performance through do** engineering. For instance, Avasarala et al. introduced N into Ge–Se to eliminate some of the Ge dangling bonds, resulting in a shift of the mobility edge, hence increased mobility gap, and reduced Ioff (Fig. 7a) [32]. As the content of N increased from N1 to N3, the trap states became deeper (0.54–0.7 eV), reducing defect density and minimizing leakage current from ~ 5 × 10–8 A to ~ 10–10 A, yet causing a sharp increase in Vth from ~ 2.8 eV to ~ 4.5 V (Fig. 7a). Moreover, N do** effectively enhanced the thermal stability of the material (> 450 °C). On the other hand, C do** in Ge–Se led to an increase in Ioff up to ~ 10–7 A and a ~ 0.8 V decrease in Vth as the content of C reached C2 (Fig. 7b), which differ from N do**. Avasarala et al. believed that the increased density of trap states or introduced C-chain-based gap states after C do** was responsible for the increased leakage and the decreased Vth [32].

N- or C-doped GeSe OTS selectors. a Device structure with 3 μm × 3 μm size; I–V curves of N-doped GeSe selector; Ioff vs. different N contents; Vth vs. different N contents. b Ioff vs. different C contents; Vth of C-doped samples; T dependence of subthreshold conduction fitting confirming Poole–Frenkel conduction; trap positions and densities. Adapted with permission from [32]. Copyright 2017, IEEE

Similarly, Sb do** decreases Vth, and the higher the Sb content (Sb < 22 at.%), the lower the Vth (Fig. 8) [48]. In 2021, Keukelier et al. conducted a systematic study on the effects of do** elements on the thermal stability and OTS performance of the Ge–Se system, focusing on Zr (metal), B, Sb (metal-like), C, and N (non-metal) [49]. Their results showed that B do** lowered the crystallization temperature, while Zr do** initially lowered it and then surpassed the pristine material temperature at 5 at.% (Fig. 8b). Sb do** initially increased the crystallization temperature, but started to decrease after reaching 26 at.%. C do** significantly raised the crystallization temperature, with a temperature exceeding 400 °C at 8 at.%. Further N do** increased the crystallization temperature to 600 °C (Fig. 8b). No matter metallic or metalloid elements are doped, the alternating current (AC) Vth of the sample had little difference and remained about 1.5 V (Fig. 8c). C/N and B do** reduced leakage current, while Sb and Zr do** increased it (Fig. 8e, f). In Ge–Se, Ge–Ge homopolar bonds contributed to leakage current, and N do** reduced homogenization and leakage current. Do** with only N led to excessively high operating voltages, while do** with only C increased leakage current. The most suitable approach was believed to be C and N co-do**. Overall, Sb and Zr contents above 10 at.% modulated the crystallization temperature to exceed 400 °C. In the study, metal and metalloid elements even decreased the crystallization temperature at low do** concentrations (< 3 at.%), while the non-metal element C effectively increased the crystallization temperature at relatively low do** concentrations. Regarding the impact on electrical characteristics, metal elements were more effective in reducing the Vth and Vff (Fig. 8g).

C/Sb/B/N/Zr-doped GeSe OTS selectors. a Device structure with 6 um size. b Crystallization temperature Tc. c Alternating current (AC) Vth. e Pristine leakage at 1 V/2 V. f Ioff. g Vff voltage. Adapted with permission from [49]. Copyright 2021, AIP Publishing

The element As, despite being considered environmentally unfriendly and requiring specific fabrication processes, plays a significant role in the optimization of Ge–Se OTS materials. Most importantly, Ge–Se–As–Si–based OTS material was believed to be the one used in the commercial 3D Xpoint in 2017 [11]. The IBM/Macronix team, focusing on PCM, conducted continuous research on the Ge–Se–As system [50,51,52]. Cheng et al., by optimizing the content of Ge and As, successfully increased the materials’ crystallization temperature to over 450 °C and achieved a low Ioff of 10–10 A, a large Jon of 7.9 MA cm−2 and the device endurance exceeding 6.9 × 1011 cycles (Fig. 9a) [50]. Using this selector, 1S1R (OTS + PCM) structure was successfully fabricated, demonstrating a ~ 2 V memory window, a 300 ns speed and > 1012-cycle read endurance (Fig. 9b). Subsequently, the team further improved the Ge–As–Se system by do**. The introduction of Si in Ge–Se–As devices extended the endurance to 1011, while do** Te resulted in Ge–Se–As–Si devices with enhanced thermal stability up to 500 °C and endurance reaching 1011. In 2021, they also addressed the trade-off issue among Vth, Ioff, and cycling endurance in B-, C-, and S-doped OTS selectors. Furthermore, In-doped Ge–Se–As OTS devices exhibited low Ioff (~ 0.1 nA), high endurance (~ 1010 cycles), and inhibition of Vth drift, while minimally affecting Vth and Ioff [52].

Ge–Se–As OTS and 1S1R cells. a OTS device with 350-nm plug; > 450 °C thermal stability; I–V curves showing 3.5 V Vth and ultralow Ioff (131 pA@2 V); 6.9 × 1011-cycle endurance. b 1S1R stacking structure; I–V curves showing ~ 2 V memory window; 300 ns speed and > 1012-cycle read endurance. Adapted with permission from [50]. Copyright 2021, IEEE

In terms of fabrication techniques, in 2023, Jun et al. employed the atomic layer deposition (ALD) process to fabricate Ge–Se–S-based OTS devices [53]. The novel Ge–Se–S material exhibited a slightly larger Vth drift compared to GeSe2. However, it demonstrated several advantages, including a lower Ioff, and a smaller Vth fluctuation up to 106 cycles. The successful application of the ALD process in the fabrication of Ge–Se system OTS devices is expected to contribute to the further miniaturization of 3D cross-point (Xpoint) memory and the realization of 3D Vertical memory in future.

Table 2 summarizes device performances of Ge–Se-based OTS selectors. Clearly, Ge–Se-based OTS selectors present thermal stability of > 350 °C, Jon ranging from 0.1 to 23 MA cm−2, Ioff ranging from 10–7 to 10–10 A, Vth ranging from 1.4 to 4 V, Vhold ranging from 0.5 to 1.8 V, endurance ranging from 106 to 1011 cycles.

3.2 Te-based OTS

Tellurium (Te) is the 52nd element on the periodic table, with an atomic radius of 1.4 Å (Fig. 10). Te exists in the trigonal crystalline state at room temperature since it has an ultralow crystallization temperature of −10 °C [58]. Trigonal Te shows a band gap from 0.33 eV to 1.43 eV as the thickness decreases, and has a melting point of approximately 450 °C [59]. Te plays a significant role in the development of OTS materials, as evidenced by the first discovered As–Te–I OTS system, as well as the pioneering Te–As–Si–Ge OTS materials. However, despite the extensive exploration of various ternary and even binary Te-based chalcogenides exhibiting OTS behavior, the intrinsic properties of Te as a standalone element have long been overlooked. It wasn’t until 2021 that Shen et al. discovered elemental Te selector switch based on the novel crystal-liquid–crystal phase transition mechanism, intrinsically differing from conventional OTS selectors [60]. Pure-Te device exhibited a large drive current density > 11 MA cm−2, a rather high selectivity of 103, a Ioff < 10−6 A, and a fast switching speed < 20 ns [60, 61]. The ~ 0.95 eV Schottky barrier formed at Te/TiN interface enabled an Ioff of 0.4 μA, which reduced to ~ 50 nA after 35 at.% Zn-do** and further to 88 pA after 50 at.% Mg-do** with a large 3 eV mobility gap. Noticeably, resembling the elemental Te cell, the Zn/Mg-doped Te layer remained in the crystalline state in the off-state [62, 63].

Binary Te-based systems have attracted attention due to their simplicity in composition and environmental friendliness. Among binary Te OTS materials, Ge–Te alloys is the earliest studied and popular OTS matrix. In 2012, Anbarasu et al. first reported that GeTe6 cell surprisingly presented an OTS behavior, rather than an OMS one found in typical GeTe device, with 5 ns fast switching speed and 0.65 mA Ion and 600-time cycles (Fig. 11a) [64]. Then GeTe4 OTS materials were also found by Velea et al. (Fig. 11b) [65], the Vth of which increased from 1.2 eV to 1.55 V and the on/off ratio degraded from 5 × 103 to 102 (compared to GeTe6). Since the low mobility gap width of Ge–Te materials ranged from 0.33 to 0.9 eV (Fig. 10d), Ge–Te OTS selector presented a low Vth of < 1.7 V@ 20 nm thick. Ge–Te devices exhibited good consistency among different device units, with low fluctuations observed during multiple tests of the same device unit. However, the narrower mobility gap also led to a large leakage current > 10–8 A. Additionally, as pure Te crystallizing at −10 °C, the highest crystallization temperature was found to only ~ 260 °C even increasing Ge content to 33.3 at.% (GeTe2) (Fig. 10b), far lower than the 400–450 °C required for the BEOL process. It also means that the Ge–Te films are more likely to crystallize during switching, which is one of the main reasons for the reduced endurance of the OTS selector (< 1000 cycles) [64]. From a bond energy perspective, the Te atomic radius is 1.4 Å, and the Ge–Te bond energy is 192 kJ mol−1 [66], indicating longer bond lengths and weaker bond energies. This makes it less capable of withstanding high temperatures and large current.

Ge–Te and Si-doped Ge–Te OTS selectors. a Time-resolved measurement, switching speed, Vhold, and endurance of GeTe6 OTS cells. Adapted with permission from [64]. Copyright 2012, AIP Publishing. b DC I–V curves of GeTe4 and GeTe6 cells; DC I–V curves of Si-doped GeTe6 cells; Crystallization temperature and trap positions of Ge–Te, Si-doped GeTe6, and Si–Te materials [64, 65]. Adapted with permission from [65]. Copyright 2017, Springer Nature

In order to solve the problem of insufficient thermal stability of GeTe6 itself, Velea et al. proposed three optimization paths: reducing Te content, adding Si element, and directly replacing Ge with Si to form Si–Te system [65] (Fig. 11b). The reduction of Te content alone cannot significantly increase the crystallization temperature; in that report, the maximum increase was only 45 °C, and there was a clear bottleneck for further improvement. After 2 at.% Si do**, it exhibited OTS switching behaviors in current-limiting tests [67], whereas non-volatility occurred as the Si content exceeds 5 at.% [68]. Besides, to improve the thermal stability and reduce the Ioff, in 2021, Wu et al. [35] doped C into the Ge–Te alloy, which sharply extended the device lifetime to > 1011-cycle and exhibits an Ioff < 5 nA, a switching speed about 5 ns, and a Vth of 1.3 V (Fig. 12a). In the same year, Wang et al. [69] also investigated 5 at.% C-doped Ge–Te OTS selector, presenting Ion = 2 mA, Ioff = 2 nA, 8.5 ns on-speed, and > 107 cycles endurance (Fig. 12b).

Ge–Te–C OTS selectors. a Device structure (30-nm plug), AC I–V curves, switching speed, and endurance of Ge–Te–C OTS cells reported by Wu et al. [35]. b Device structure (250-nm BE), DC I–V curves, on-switching speed, and endurance of Ge–Te–C OTS cells reported by Wang et al. Adapted with permission from [69], Copyright 2021, IEEE

Ambrosi et al. from TSMC further incorporated N into the Ge–Te–C OTS materials to improve the thermal stability above 400 °C [70], enabling even smaller performance fluctuations, reducing parameter dispersion such as Vth after multiple operation, and exceeding 1011 cycles (Fig. 13a). The further introduction of Si elements into the system enhanced the robustness of the device. The thermal stability and high-current tolerance of the Ge–Te–C–N–Si system were further enhanced. The device’s thermal stability could be improved to above 450 °C, and the voltage drift was reduced compared to the Ge–Te–C and Ge–Te–C–N systems, resulting in significantly improved device reliability with endurance > 1010 cycles (Fig. 13b). Additionally, by controlling the Ge content, modulation of defect states in the Ge–Te–C–N–Si system could effectively reduce the difference between Vff and Vth within a specific compositional range, achieving a "firing-free" effect [71] (Fig. 13b). This optimization further reduced the requirement for I/O voltage in application scenarios and facilitated the application of OTS devices in more advanced process nodes.

Ge–Te–C–N (a) and Ge–Te–C–N–Si (b) OTS selectors. a Device structure of a Ge–Te–C–N OTS cell (32–72-nm plug); 100 DC switching cycles; Cumulative probability plot of Vth; Endurance. Adapted with permission from [70]. Copyright 2021, IEEE. b Device structure of a Ge–Te–C–N–Si cell (~ 40-nm plug); DC I–V curves after repeated operation; Firing-free optimization plot showing firing-free behavior in GeD composition; Endurance. Adapted with permission from [71]. Copyright 2022, IEEE

Besides C/N/Si do** in Ge–Te OTS cells, the toxic As elements were often incorporated. In 2019, Garbin et al. provided a comprehensive analysis of the effects of the As/Te ratio, Ge and Si content in the Ge–Te–As–Si system on device performance (Fig. 14). Increasing the As/Te ratio raised the crystallization temperature [72]. The addition of Ge to AsTe reduced the mobility gap, and when the Ge content in Ge–Te–As exceeded 20 at.%, the crystallization temperature increased to 450 °C. However, the mobility gap decreased and leakage current increased. The addition of Si increased the mobility gap, raised the crystallization temperature, increased the threshold voltage (Vth) to a range of 2.3–2.9 V, and reduced leakage current to 10 nA. In the Ge–Te–As–Si system, strong bonds were formed, resulting in a temperature-stable amorphous network with excellent endurance (1011 cycles).

Ge–Te–As OTS selectors. a Device structure (65-nm plug). b Endurance of As-rich Ge–As–Te–Si OTS devices with different Si content. c Crystallization temperature, moving from Ge–Te–As to Ge–Te–As–Si system increases > 450 °C. d Comparison of calculated element diffusion coefficient at 600 K for GeSe and Si–Ge–As–Te. e Endurance of 1011 cycles achieved Ge–Te–As. Adapted with permission from [72]. Copyright 2019, IEEE

Lee et al. further enhanced the thermal stability to above 500 °C by introducing nitrogen (N) into the Ge–Te–As–Si and solved the performance degradation with repeated cycling and reliability after BEOL process (Fig. 15) [73]. A Ion of 0.1 mA was obtained, which were found to be size-dependent. For a 30 nm cell, a Jon > 11 MA cm−2 was found. Their cycling performance was shown to be greater than 108 cycles. Also, they demonstrated a 1S1R memory cell using a Ta2O5/TaOx resistance memory with the GeTeAsSiN selector device.

Ge–Te–As–Si–N OTS selector and 1S1R cell. a Device structure with 30 nm–100 um size. b Thermal stability above 600 °C. b DC I–V curves. c DC I–V curves of the selector with varying sizes. e Scaling behavior. f Endurance. g 1S1R structure with Ta2O5/TaOx memory cell. h DC I–V curves of the 1S1R cell. Adapted with permission from [73]. Copyright 2012, IEEE

Beside the Ge–Te-based OTS materials mentioned above, there are some binary Te-based OTS materials worth mentioning, including Si-doped, C-doped, B-doped, and Al-doped Te; most of them were first reported by Kazuhiro Ohba and Hiroaki Sei from Sony corporation in 2015 [74]. In their filed OTS patents, they also investigated N, O, Mg, Ga, Y etc. incorporation, for thermal stability enhancement and leakage current reduction, and multi-element do**. They further noticed that the insertion of 2–5 nm high-resistance layer between the OTS layer and electrode, like SiOx, AlOx, MgOx, SiN, and HfOx, could greatly reduce the Ioff to sub-nA and even pA. For Si–Te OTS materials, Velea et al. mentioned the crystallization temperature of Si–Te system increased significantly with the decrease of Te content, it could reach 400 °C when Te < 50 at.% [65]. Similar results were found in Koo et al.’s work [75]. The difference was that the electrical performance of Si–Te reported in the former paper was seriously degraded, the selectivity of other Si–Te components was less than 5 except for SiTe6 (~ 100), while Koo et al. reported that Si–Te device had good performance, including an Ion of 5 × 10−4A, Ioff of ~ 1 nA, thermal stability up to 400 °C, and endurance up to 108 cycles.

The C–Te system is another Te-based OTS material that has been extensively reported recently. In 2018, Chekol et al. chose carbon (C) as a component in the C–Te OTS device [77], which had a smaller atomic radius compared to Ge and Si. The C–Te OTS device exhibited a switching ratio greater than 105, a current density higher than 11 MA cm−2, an Ioff current of approximately 1 nA, high endurance of around 109 cycles, and thermal stability exceeding 450 °C (Fig. 16b). The Vth of C–Te was relatively small (Vth = 0.64 V, Vhold = 0.36 V). C–Te was stable when the C content was between 25 and 55 at.%. As the C content increased, Vth decreased, while leakage current increased. In 2018, Yoo et al. reported the B–Te system [78], which exhibited a selectivity of 105, Ion of 5 × 10−4A, Ioff less than 10 nA, thermal stability up to 450 °C, and endurance of 108 cycles (Fig. 16b). In the same year, Yoo et al.’s comprehensive research showed that in B–Te and Al–Te-based devices [76], the decrease of Te ratio resulted in increased Vth and decreased Ioff (Fig. 16d). The endurance of devices based on C–Te and B–Te could switch > 108 cycles in maintaining low Ioff, while the Al–Te-based device showed Ioff degradation after 107 cycles (Fig. 16d).

C–Te, B–Te, and Al–Te OTS selectors. a Device structure with 30–150 nm size. b DC I–V curves. c Relation between thermal stability and atomic radius difference. d Ioff, Vth and endurance. Adapted with permission from [76]. Copyright 2018, IEEE

Table 3 summarizes the device performances of Te-based OTS selectors. Te-based OTS selectors present a Jon ranging from 0.44 MA cm−2 to 55 MA cm−2, an Ioff ranging from 10–7 A to 10–9 A, a Vth ranging from 0.75 V to 2.2 V, and a Vhold ranging from 0.3 V to 1.5 V, and an endurance ranging from 600 to 1011 cycles. Although Ge–Te OTS materials show lower than 250 °C thermal stability, the incorporation of light atoms (with a smaller radius) or the replacing of Ge by these atoms, forming strong bond and robust amorphous network, significantly improve the thermal stability above 400 °C, enabling the withstanding of the BEOL process in the memory fabrication.

3.3 S-based OTS

As the most representative element in the chalcogen, the 16th element sulfur (S) has been the subject of numerous investigations, regarding its crystal structure [84,85,86,87,88,89], electronic structure [84, 85, 90,91,92], thermodynamic properties [84], and other physical characteristics (Fig. 17a). The crystallization temperature of pure S is about 0 °C and the melting point is 115 °C [93]. In 2020, Jia et al. first reported S-based OTS materials [66], GeS, and then Ge–S alloys were systematically studied. Since the atomic radius of S atoms was just 0.88 Å, > 0.3 Å smaller than Se and Te atoms, the Ge–S compounds exhibited high crystallization temperatures, 380 °C for GeS and exceeding 600 °C for GeS2 [92]. The mobility gap of Ge–S system increased with an elevated concentration of S, for S-rich Ge–S, the mobility gap ranged from 2.6 V to 3.4 eV and it could reach 3.8 eV in pure S (Fig. 17b, c) [94]. Consequently, Ge–S-based OTS device exhibited a rather low Ioff. The Ge–S bond energy is 266 kJ mol−1 [66], indicating a strong bond that enables the material to withstand higher temperatures and larger passing current.

In 2020, Jia et al. discovered novel GeS OTS devices from the perspective of constructing a more stable amorphous system [66]. The device consisted of W bottom electrode with a diameter of 190 nm, Al top electrode, and the 10-nm-thick GeS layer sandwiched between them (Fig. 18a). Due to strong Ge–S bond and wide mobility gap of GeS (~ 1.5 eV), the GeS selector exhibited high drive current ~ 10 mA (Jon = 34 MA cm−2) and low leakage current ~ 10 nA (Fig. 18b). The Vth in the selector was ~ 3.2 V, while the Vhold was ~ 0.3 V (Fig. 18b). The GeS OTS device demonstrated favorable bi-directional selectivity and scalability (Fig. 18c), with a high switching speed (ton ~ 10 ns, toff ~ 100 ns) (Fig. 18d), an on/off ratio of approximately 106 and endurance exceeding 108 (Fig. 18e). In terms of thermal stability, the device maintained switching performance after annealing at 350 °C. Considering the trade-off between selectivity ratio and high driving current, GeS devices demonstrated remarkable performances, when compared to Se and Te selectors (Fig. 18f).

It is worth noting that the top electrode in that paper was made of Al, which would cause the diffusion of Al atoms and form conductive channels in the material layer, thus affecting the switching process. In the subsequent report [95], the author reported GeS OTS devices with both TiN top/bottom electrodes (Fig. 19a). The GeS device with TiN electrodes (Fig. 19a) showed a lower Vth of 1.75 V and a higher Vhold of 0.75 V (Fig. 19b, c), the selector exhibited an Ion of 1 mA, and large current density ~ 35.4 MA cm−2 in 60 nm-sized devices (Fig. 19d). Noticeably, the off-speed in this selector is more than 10 times faster (~ 7 ns) than the previous one (Fig. 19e), indicating that the diffusion of Al slowed down the switching process (also increased the Ion), but this effect did not lead to significant changes in the main switching mechanism of the device, which was still an OTS switching. Compared with other selectors, GeS OTS selector still had obvious advantages in the drive current density and could be further improved with the feature size scaling down (Fig. 19f).

GeS OTS device with TiN electrodes. a Device structure with 60–200-nm plug. b AC I–V sweeps. c, d Vth, Vhold, Ion and Ioff dependence on the electrode size. e On/Off speed; f Comparison of the Jon of the GeS OTS cell with other Te- and Se-based selectors [95]. Adapted with permission from [95]. Copyright 2021, John Wiley and Sons

In 2023, Wu et al. reported the Ge–S–As OTS device with various As concentrations and systematically elaborated the key role of As element in OTS switching [96]. They discovered that incorporation of As into GeS brought a more than 100 °C increase in crystallization temperature (> 450 °C) (Fig. 20a, b), improving the switching repeatability and prolonging the device endurance (~ 1010 cycles), which was attributed to the strengthened As-S bonds and sluggish atomic migration after As incorporation. The addition of As reduced the leakage current by more than an order of magnitude (Fig. 20e, f) and significantly suppressed the operational voltage drift, ultimately enabling a BEOL-compatible OTS selector with a Vth of 2 V, an Ion higher than 12 MA cm−2, an on/off ratio over 104, a speed about 10 ns, and an endurance approaching 1010 cycles after 450 ℃ annealing (Fig. 20h).

GeSAs OTS selectors. a, b Device before/after 450 °C annealing. c, d I–V curves of Ge–S–As devices before/after 450 °C annealing. e, f DC I–V curves of devices before/after 450 °C annealing. g, h Endurance performance of Ge–S–As before/after 450 °C annealing. Adapted with permission from [96]. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature

In 2021, Kim et al. fabricated GeS2 and Ge2S3-based OTS devices using the plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition (PE-ALD) [94]. Through comprehensive considerations of factors such as growth temperature and purging time of the GeCl4 precursor, the team discovered that PE-ALD Ge1-xSx, utilizing an H2S/Ar plasma reactant, exhibited a self-limiting growth behavior within an ALD window. As a result, the team successfully fabricated GeS2 and Ge2S3 films by ALD, which exhibited thermal stability up to 600 °C (Fig. 21a). The 15-nm-thick GeS2 device exhibited an Ion of 0.1 mA, a Vth of approximately 5 V and a Ioff of 20 nA. The trade-off relationship between the Vth (1.9–6.2 V) and the normalized Ioff (20–250 nA) was observed by scaling down the film thickness from 30 to 5 nm (Fig. 21a). Surprisingly, Ge2S3 OTS devices required lower Vth owing to lower trap density according to the Poole–Frenkel fitting (Fig. 21a).

Ge–S OTS selector. a Device structure with 50-nm plug; Thermal stability of GeS2 above 600 °C; DC I–V curves of GeS2 and Ge2S3 cells; Ioff. Adapted with permission from [94]. Copyright 2021, Royal Society of Chemistry. b Device structure with 60-nm plug; DC I V curves of Ge–S devices; Ioff and Vth comparisons [53, 94, 97]. Adapted with permission from [97]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier

In 2023, Lee et al. from the same group continued the exploration of Ge1−xSx series OTS devices [97], which revealed that Ge-rich compositions (0.2 ≤ x < 0.5) exhibited metallic behavior due to Ge crystallization caused by Joule heating. On the other hand, devices with S-rich compositions (0.5 ≤ x ≤ 0.67) demonstrated OTS behaviors (Fig. 21b). As the S content increased, the material’s mobility gap widened from 1.65 eV for Ge2S to 3.45 eV for GeS2. Consequently, the devices exhibited increased Vth (ranging from 3.4 V to 5 V), reduced Ioff, with the lowest reaching 1.3 nA (Fig. 21b). The endurance of the devices reached up to 109 cycles, and the devices exhibited thermal stability up to 600 °C. Note that mobility gap values of Ge–S alloys in this work was > 1 eV larger than reported film samples which may be due to the material contamination [97].

In 2022, Matsubayashi et al. conducted high-throughput calculations to screen environment-friendly ternary OTS materials [98]. The first screening filter was element exclusion to narrow down the combinations. They focused on the 14 elements: B, C, N, Al, Si, P, S, Zn, Ga, Ge, In, Sn, Sb, and Te, the ternary combination of which generated about thirteen thousand compositions (10% atomic fraction step, Fig. 22a). The second screening filter was the glass-transition temperature > 600 K, required for BEOL process, by which about six thousand compositions left. The third screening filter was the 5 valence-electron rule to populate the antibonding state (unstable) and activate the OTS behavior (Fig. 22b). For the about 1500 compositions that passed the above screening, they computed the formation energies and the electronic properties from first-principles. After considering formation energy < 0 eV atom−1 (chemical stability), low leakage current, immunity to phase demixing, application-specific trap/mobility gaps and change in polarizability, they finally identified 11 promising OTS materials (Fig. 22f), including P0.2S0.4Ge0.4, Si0.3S0.5Sn0.2, Si0.3S0.5Ge0.2 etc. Clearly, all these candidates were S-based compounds, indicating the application potential of S-based OTS materials [98, 99].

Screening environment-friendly OTS materials. a The first screening filter of element exclusion for new OTS materials. b The screened compositions for the valence electrons number per atom Nve, the glass-transition temperature (Tg) and the 5 valence-electron rule. c Mobility gap Eμ and trap gap ΔEt. d Formation energy Eform and trap gap ΔEt. e Element breakdown of screened compositions. f Summary of 11 promising OTS compositions of selector materials [98]. Adapted with permission from [98]. Copyright 2022, IEEE

Different from the above computational screening, Wu et al. performed a systematic materials screening of chalcogenides from the periodical table of elements using three essential criteria—few elements (easy fabrication), wide mobility gap (low Ioff), and thermal stability > 400 °C (withstand BEOL process) [100]. The anions were S, Se, or Te, while cations of these chalcogenides were from group III to V located at metal–semiconductor boundary (Fig. 23a), which were widely used in phase change materials. After the above three essential criteria filtering, Ga–S was selected as the final research target due to its high mobility gap of ~ 2.53 eV and high crystallization temperature of ~ 550 °C (Fig. 23b). Photothermal deflection spectroscopy experiment detected high-density traps in GaS materials required for OTS behavior (Fig. 23c). Further device results confirmed that Ga–S-based devices exhibited typical OTS switching behaviors, with a high drive current density Jon of ~ 21.23 MA cm−2, a low Ioff of ~ 10 nA, and a Vth of ~ 2.5 V (Fig. 23d-f).

GaS OTS selectors. a Pick out the cation and anion from the periodic table. b Band gap and crystallization temperature of these binary chalcogenides. c Experimentally reconstructed qualitative energy band schematic. d Device structure with 60-nm plug. e DC I–V curves. f Comparison of the Ioff and Jon with other reported selectors [100]. Adapted with permission from [100]. Copyright 2022, John Wiley and Sons

Table 4 summarizes the device performances of S-based OTS selectors. As expected, S-based OTS selectors present large a Jon ranging from 5 MA cm−2 to 34 MA cm−2, an Ioff ranging from 10–8 A to 10–9 A, a Vth ranging from 2 V to 5 V, and an endurance > 108 cycles. A high thermal stability of > 350 °C and even 600 °C was also obtained. Clearly, Se-, Te-, and S-based OTS materials have their own advantages and limitations. The actual optimization process involves integrating these advantages and overcoming their shortcomings. This is why many OTS materials are combinations of these three sub-systems. Indeed, multi-component OTS materials have many performance advantages, but the increasing complexity of their compositions also brings numerous challenges. The complex multi-component systems make it difficult to achieve atomic-level compositional uniformity in OTS material thin films, and precise control of element ratios is also challenging. Consequently, complex multi-component systems are not easily prepared using advanced conformal processes such as ALD, which hinders the application of these materials in high-density 3D vertical architecture.

4 Switching Mechanisms of OTS

4.1 OTS Models

Since the discovery of OTS materials, many models were developed to explain the threshold switching phenomenon [16, 29, 101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110]. For instance, Kroll et al. proposed a thermal runaway model [103, 104] that explains the OTS as the result of a Joule heating process, which triggers a positive feedback loop for carrier generation and leads to an exponential increase of the conductivity. Nevertheless, the thermal model could not capture one of the most relevant feature of OTS: negative differential resistance (NDR) [111, 112]. While the thermal models were successfully applied to describe the NDR in single-crystal Si-doped YIG [113], in crystalline, large-gap semiconductors the NDR is not the result of an ovonic threshold switch. By the early 1980s, the thermal model was overthrown by the electric-field-driven OTS models [101, 114] that will be discussed below.

In PCM materials, OTS is the precursor mechanism of the ON switching that induces a local Joule heating process and the eventual crystallization of the amorphous into a high-resistance state phase. In this framework, Karpov et al. [105,106,107] introduced a field-induced nucleation model that assumes that the crystalline growth section, described as being a conductive cylinder in Fig. 24a, proceeds only once past a critical nucleus size of the filament. If the nucleus size is smaller than the critical size, the crystal seeds revert back into their amorphous phase upon field removal. This model is able to describe the drift dynamics of the threshold voltage upon device operation, highlighting the need to consider the amorphous matrix relaxation when dealing with drift dynamics. Its disadvantage is that it is not directly linked to the electronic properties of the material and hence does not properly account for its conductivity [23]. However, if one makes abstraction of the conductive cylinder/crystal grain/rod as to regard it as a (meta) stable (Ohmic) conductive local atomic percolation path, it contains an important ingredient for the universal OTS model; namely the bi/metastable state of the amorphous matrix and its associated relaxation time that defines the material parameter drift dynamics.

Copyright 2007, AIP Publishing. b Carrier injection model—e/h free carriers are injected on both sides, neutralizing VAPs, which do not interfere anymore with the electronic transport. Holding voltage corresponds to the mobility gap energy. Adapted with permission from [115]. Copyright 1973, IEEE. c Small polaron model—trapped charge carriers modify the local atomic bonding environment. This bond rearrangement modifies the local morphology of the materials and reduces the carrier mobility considerably. Above a critical quasi-particle density, the destructive interference of the atomic displacements does not hamper the carrier transport any longer. d Density of States (DOS) for the 2-electron and 2-hole vs. their one-particle energies in amorphous matrix, where rare, special, local negative-U centers showing strong polaron effects provide its Fermi level pinning. Adapted with permission from [110]. Copyright 2012, AIP Publishing

a Field-induced nucleation model—the nucleation of conductive crystallite is in a highly resistive amorphous matrix that concentrates the electric field and drives the filament growth until the device is being shunted. Adapted with permission from [107].

On the other hand, electronic switching models [102, 115,116,117,118,119,120] have been proved to be the most successful in describing the OTS conductivity and hence their associated threshold switching. In those models, the atomic bonding relaxation is not explicitly considered. However, many models consider the electron–phonon interactions or polaron relaxation implicitly. For instance, Ovshinsky [16] originally proposed an electronic mechanism at the origin of the threshold switching. The conduction was supposed to be phonon-assisted hop** near the Fermi level and not due to excited carrier conduction in the bands. The carrier injection model [115, 116] describes the conduction to be initiated when electrons and holes injected from cathode/anode compensate the positive/negative valence-alternation pairs (VAP) [101, 121,122,123] throughout the layer. The injected free carriers are transported in the mobility edges of the density of states. The holding voltage, therefore, reflects the mobility gap of the material (Fig. 24b), a correlation which was actually observed in a set of nine OTS materials [124]. Adler et al. [101] interpreted the threshold switching as originating from an impact ionization (II) process and formally described the NDR as being a competition between a carrier generation process (driven by both electric field and carrier densities) and a Shockley–Hall–Read (SHR) recombination. The model takes into consideration the electronic structure of the amorphous materials and together with the VAP theory [121], gives a detailed interpretation of the changes that (might) occur at the atomic/electronic level. It is worth noting that the model considers a local bond rearrangement/coordination change that takes place upon charge trap** on defects, which is a short-range (intimate valence–alternation pair) mechanism and does not require any atomic drift or diffusion when the material switches on or off. In other words, the impact of atomic relaxation upon defect charging was only implicitly hinted. Redaelli et al. [102, 117] improved this description by adding an avalanche-like multiplication phenomenon to the list of carrier-generation mechanisms.

Emin’s [125] small polaron model of subthreshold conduction was motivated by small measured Hall mobilities. From that perspective, the switching corresponds to the moment when the density of small polarons increases sufficiently to reach a steady-state threshold, namely when adjacent polarons show destructive interference and cancel-out the atomic displacements of other polarons (Fig. 24c), which breaks the carrier-phonon interaction. This model was challenged by high quality Hall measurements [126]. Also, since in the amorphous matrix the strong small-polaron interactions can occur at rare, special and local bonding arrangements [110], the polaron-like band transport is prohibited. Nevertheless, the model highlights the role of local atomic relaxations that impact on the electronic conduction and therefore on the OTS mechanism. For instance, the 2 electron-2 hole “intimate pairs” will pin the Fermi level (Fig. 24d) and the switching on can be successfully described by soft atomic potentials that exhibit the double-well potential signature with two states [110, 127].

Ielmini et al. [118, 119] introduced a high-field Poole–Frenkel (PF) transport threshold switching model, where the traps are located deep in the mobility gap (Fig. 25a) and trigger the switching of the Ion current at a certain non-equilibrium occupation of higher-energy traps. This results in a substantial nonuniformity of the electric field in the amorphous matrix. The model includes the implicit relaxation of the atomic matrix, irrespective of its physical origins (polaron relaxation or thermal vibrational contributions) to the trap energy through thermally-assisted hop** or tunneling mechanisms. The capacity of this model to describe the complete current–voltage signature contributed to its popularity.

Copyright 2008, American Physical Society. b At threshold field, the carrier injection results in a nonuniform internal electric field, higher at the cathode, non-equilibrium trap occupation, generation of secondary electrons with high mobility and the OTS can be sustained afterward, even at lower fields. Adapted with permission from [120]. Copyright 2023, John Wiley and Sons

a Poole–Frenkel model capture-emission depends on the trap energy depth (relative to the mobility edges) and density (inset: denser traps interact and the emission barrier reduced not only by the field, but also by the trap proximity), local phonon-related relaxation energy (vertical dashed arrow) can also be accounted for. Emission time is exponential on the trap depth; therefore, the effective carrier mobility increases in the direction of the electric field. This simple model takes the average trap properties. Adapted with permission from [119].

A revisited version of the impact ionization and PF models was recently introduced by Fantini et al. [120] in a bipolar avalanche model, which describes the conduction as PF by majority holes at low electric field. These evolve into bipolar avalanche multiplication and ultimately the threshold switching is being triggered by this electron–hole cooperation, leading to a larger electron mobility compared to the hole one (Fig. 25b).

Buscemi et al. [108] introduced a hydrodynamic-trap-assisted-tunneling (TAT) model that considers the occurrence of temporary and progressive localization-delocalization of the states, creating conductive channels inside the insulating matrix. The transition rates are increased upon the switching voltage as function of the excess energy from the hydrodynamic-TAT model solution. Aside from unclear atomic-electronic interaction mechanisms, the last two models are capable to reproduce most (if not all) experimental measurements of the OTS devices.

Degraeve et al. [127] used a two-state model with a double-well potential to describe the metastable percolation path/cluster/channel in the threshold switching. This approach makes abstraction of the exact details of the physical mechanism, but allows for a completely analytical solution for any arbitrary defect cluster. Thus, the model is capable of capturing technologically important phenomena like cycle-to-cycle and device-to-device variations within an acceptable computation time. Apart from electronic effects, the two-state model also considers self-heating. In particular, the switch-off is identified as temperature-controlled.

In the following, first-principles evidences are provided to unravel the nature of electronic properties and the nature of mobility gap traps in amorphous OTS chalcogenide materials. Their interaction with the electric field is discussed and the accompanying polaron relaxation mechanism that occurs upon charge redistribution in the amorphous systems. Finally, a discussion on the most plausible OTS mechanisms is given.

4.2 Electronic Structure of Disordered Materials

In analogy to crystalline semiconducting materials, the electronic structure of glassy/amorphous semiconducting materials can be described by a gap between the valence and conduction (mobility) edges (in contrast to bands in crystals), with additional tail and/or gap states in-between that are localized in space. These gap/tail states can act as electron or hole traps (or defects) [128]. Traditionally, the electronic structure and possible transport mechanisms are discussed in terms of these electronic structure defects. Kastner et al. [121] introduced labels for the under-coordinated \({C}_{1}^{-}\) and over-coordinated \({C}_{3}^{+}\) chalcogenide atoms to represent the defect states that accepted/donated charges, calling them valence-alternation pair (VAP). In the same framework, over-/under-coordination can be extended to the elements of the group V (pnictogens 2P3 = P4+ + P2−) and IV (tetragons 2T4 = T5+ + T3−) [129,130,131] of the periodic table. The length of the trap localization is of the order of 1.5–2 nm [131]. This implies that atomistic models must meet a minimum size requirement. Typically, for density-functional-theory (DFT) simulations to be affordable, a model size of ~ 2 nm results in a trap concentration of ~ 1021 cm−3. This is a rather large concentration, compared to ranges measured of 1018–1019 cm−3. Despite this artificially high trap concentration, DFT simulations provide a glimpse at the electronic signature of the chalcogenide materials. Investigating various compositions of GexSey, with x:y = [50/50 Ge-rich, 30/70 Se-rich], Clima et al. [129, 130] observed over-coordinated Ge5+ (electronic traps) and under-coordinated Ge3− (hole traps) VAP states or Se non-bonding lone pairs (LP) (hole traps) localized states in Se-rich compositions (Fig. 26a), whereas in Ge-rich models there were mostly Ge–Ge chains of atoms, playing the role of electron/hole traps (Fig. 26b). It was shown that even within the fixed-atoms approximation, the electric field has a strong influence on the energy and localization length of the tail states.

a Typical DOS in 2 × 2 × 2 nm Se-rich aGe30Se70 model with few Se-LP, Ge3−/Ge5+ VAP gap/tail states representations as insets. b Typical DOS in 3 × 3 × 3 nm Ge-rich aGe50Se50 model with few representations of gap/tail states. The red line denotes the Fermi level, the green line-the first empty state. The Se lone pairs and non-tetrahedral/co-linear bonds around Ge are typical for the mobility gap traps. Adapted with permission from [129]. Copyright 2020, John Wiley and Sons

An applied electric field can promote electrons to higher energy states. If the higher-energy states are of antibonding character, the local bonding will be weakened and become unstable after this electronic excitation. The probability of encountering an electron promotion to the antibonding state is high in amorphous chalcogenides that have on average five valence electrons per atom (the 5 valence-electron rule [132, 133]). Konstantinou et al. [134] elaborated in details on the effect of the electric field on the mid-gap states in amorphous Ge2Sb2Te5 chalcogenide. It has been shown (Fig. 27) that 1–2.5 MV cm−1 applied electric fields are capable to break/reconnect and change the local coordination around the atoms hosting the localized mid-gap electronic state. This removes the trap from the mid-gap by transforming it into a delocalized conduction-edge state. This local instability is key in activating the OTS mechanism, which reflects the transition from insulating to conducting state of the material [135,136,137]. The work clearly shows that considering the effect of the electric field on the electronic structure defect in the gap (inherently linked to the local bonding/coordination) is required, when describing the OTS mechanism.

Density of States (DOS), Inverse Participation Ratio (IPR-degree of localization) and local atomic coordination for the a localized mid-gap state in the absence of electric field and b under 2500 kV/cm field. Adapted with permission from [134].

4.3 Polaron Relaxation

At this level, it is interesting to understand what happens to the gap defect levels when they are getting populated. An important thing to describe the charge transport mechanism is to consider the atomic relaxation that inherently occurs during trap (de)occupation process. Nardone et al. [110] gave an elegant description of the strong interaction between the charged carriers and local atomic bonding in chalcogenide glasses. They argue that a high DOS in the mobility gap indicates that localized states in the mobility gap could provide with sufficient screening of the external field by forming a dipole layer by means of a redistribution of localized electrons [110]. This redistribution is accompanied by a set of local atomic deformations, similar to the lattice polaron relaxation but spatially localized in the amorphous matrix. In terms of atomic bonding, it can be pictured as if certain weakly bonding atomic morphologies are forming small “liquid-like” regions that got “frozen” in the solidified glass. In another context, these regions are known under the name of excitation lines or space–time bubbles [138]. Experimental evidences are pointing to the negative correlation (Hubbard/U [122]) energy nature of the amorphous chalcogenides. In other words, these doubly-occupied localized states are stabilized energetically by a polaron relaxation mechanism and single occupation exists only as excited states. These are supported by the lack of ESR signal at non-cryogenic temperatures. The Fermi level pinning with an activation energy for the conduction that is half the mobility gap supports the view that a strong polaron interaction is characteristic to the chalcogenide glasses that sets them apart from other amorphous semiconductors [110]. All these factors favor the 2e/2 h excitation model for the polaron conduction, that can well be described by a two-state model with conduction through a percolation channel [127].

Although unequivocally proving that the strong polaron interaction is responsible for electronic transport is challenging, we want to highlight in the following the importance of local structural relaxations upon trap charging by giving a few supporting theoretical findings. Raty et al. [137] studied with first-principles electronic excitations of the OTS glasses. Their results showed structural reordering, bond alignment, and appearance of local structural motifs that are characteristic of meta-valent bonds [138,139,140]. Next, the Born effective charges (BEC) of certain atoms increase drastically upon electronic excitation. These changes lead to large DOS/dielectric constant changes, hence reflecting a modulation of the conductivity of the material [141]. Noé et al. [136] argue that the bond alignment/delocalization is expected to introduce more conductive channels at the Fermi level of the amorphous OTS materials. Based on a BEC increasing upon trap charging, an OTS-gauge factor was defined to assess the material’s ability to undergo a threshold switch for theoretical screening purposes [98]. Another illustration of the impact of the polaron relaxation model in amorphous Ge50Se50 was given by Slassi et al. [142] whose results stressed the dramatic changes in the mobility gap undertaken by the amorphous matrix.

These models illustrate that atomic relaxation mechanisms are driving part of the electronic structure change taking place during the threshold switching process. That, together with the thermal Joule heating effects during switching or longer time operation of the device, leads to bond readjustments and therefore to a relaxation of the amorphous matrix with an eventual resistance/threshold voltage drift [105, 129, 143].

4.4 Conduction-Switching Mechanisms Discussion

Off-state conduction: Nardone et al. [110] analyzed various conduction mechanisms in amorphous chalcogenides. They identified, in combination with experimental data, the most plausible electronic conduction mechanisms, namely: Poole–Frenkel ionization [118,119,120], field-induced delocalization of tail states, optimum channel hop** in thin films, optimum channel field emission, percolation band conduction [127], or transport through crystalline inclusions. The latter might be relevant for PCM materials, but it can safely be excluded for non-crystallizing OTS materials. Next, space-charge limited currents are only plausible in thick films and low temperatures conditions, whereas Schottky emission and classical hop** conduction (tunneling from trap to trap) were deemed very unlikely to occur. Finally, the multi-phonon trap-assisted tunneling (TAT) [108] was successfully used in describing the off conductivity.

Switching: electronic models describe the switching process as being a non-equilibrium condition for the trap occupation that alter the electronic structure [101, 102, 115,116,117,118,119,120]. A more physical description of the threshold switching mechanism requires considering both electronic and ionic dynamics events: when the mobility gap defects/traps get populated, a local atomic bond alignment/rearrangement (polaron relaxation) leads to different trap position in energy and to a spatial (de)localization [110, 129, 131, 136, 137, 139, 144]. As a consequence, the charge transport properties change dramatically, but reversibly. Most OTS switching models describe the same phenomenon at different abstraction level using different frameworks. For instance, the small polaron model describes the onset of the conduction at the polaron density that leads to destructive interference of atomic bond deformations of nearby polarons, whereas in PF model, the same phenomenon can be described by energy-aligned close in space traps with small hop** barrier that would effectively transform the traps into a delocalized sub-band. Also, the phonon-assisted hydrodynamic-TAT model considers the local polaron relaxation with the energetic load-relaxation of the traps upon charging, whereas the two-state model accounts for it with a double-well potential between localized and charged/relaxed/delocalized states. The level of description is a trade-off between physical precision and computing speed. Important practical phenomena like device-to-device variability can only be captured when abstraction of the atomistic mechanism is taken. Consequently, it is not straightforward to dismiss certain models over others since they are all mostly complementary to each other, if not the same on the grand scale. While one could argue that many aspects of the conductivity and switching are accurately described mathematically by selecting one or combining several models (see, for instance, Fantini et al. [120] for the latest/ most comprehensible model on OTS switching), there is no definitive proof of the exact physical mechanism behind the phenomenon. It could also be that several different conduction mechanisms are active at different electric fields or in different materials. The exact atomic/electronic physical mechanisms are still difficult to prove experimentally and claim a full understanding of.

On-state conduction: In terms of spatial distribution of the current, some models treat the conductivity to occur in confined space of the device (filamentary/percolation), while others consider the conduction to be bulk-limited [118, 119]. However, when the device size is reduced, the bulk mechanism can be applied successfully to the confined space as well. Percolation conduction (optimum channel hop**, (sub)band conduction in variable trap densities) is naturally suiting amorphous materials with a conductivity field dependence as that of the PF conductivity [110]. Next, concepts based on a band conduction at the (modified) mobility edge or an impact ionization/avalanche multiplication also describe well the on-state conductivity. Indeed, the on state is not stable in absence of a flowing electrical current; as a consequence, the trap occupation state and delocalization are determined by the trap**/de-trap** dynamics. Then the rate of incoming electrons to maintain an average-full state of all the traps in the material is not sufficient, the atomic configuration around the trap** sites relaxes, leading to a charge localization and breaking the conductive cluster/percolation path/channel.

To summarize, in the subthreshold regime there is a trap-limited current that can be described by more than a single plausible physical mechanism. Electric field and charge injections affect not only the occupation, but also the localization in space and in energy of the gap traps. At threshold switching, a non-equilibrium trap occupation (possibly also delocalization) occurs, which leads to a metastable state of the (cluster of) traps that conduct the carriers leading to either a (sub)band charge transport and/or also to an impact ionization/avalanche multiplication. A mix of both electronic and hole types of conductivities is likely to take place. The metastable state of the traps is retained by the electrical current until it is not sufficient to maintain them in the high-energy state (charged state), since the de-trap** rate is out of equilibrium with the trap** one and the system reverses back to the initial state (uncharged traps). Thermal effects on atomic relaxation are important ingredients in changing the conductive properties of the percolation path in the OTS material, which define the long-term evolution of the conductive path (aging, endurance, parameter drift).

5 Applications of OTS

When OTS devices were initially proposed in 1960s, their primary application purpose was to serve as a new type of rectifier device, aiming to replace conventional diodes [20, 20, 101]. However, due to challenges related to material and fabrication compatibility, OTS selectors did not gain significant advantages over diodes in the early stages of development. The latter, together with MOSFET, dominated the electrical semiconductor in the latter half of the twentieth century. Entering the twenty-first century, as the semiconductor process node advanced, conventional diode and MOSFET-based memory technology, that is, DRAM and Flash, nearly approached the physical limit, high-density emerging memories thereby were highly desired. The OTS device, as a promising selector unit in high-density arrays, regained wide research attention and ultimately achieved successful industrial applications in 2017 [11]. Besides being a switching selector, the recently reported OTS-only self-selecting memory in 2021 is a milestone for the OTS device, aiming to achieve low-cost and high-density memory [145]. Moreover, with the rise of the concepts such as neuromorphic computing and artificial intelligence (AI), there is an increasing interest in exploring the hardware platforms and devices that serve as carriers for computational theories [146]. The OTS device, with their excellent device consistency and superior scalability, also holds significant value in the field of neuromorphic computing. In this section, these potential applications of the OTS device are discussed in detail.

5.1 3D Memory

With the deepening research on next-generation fast-speed and high-density memories, the application of OTS in 3D novel memory, particularly in 3D PCM, has gradually become one of the major directions for OTS devices. The remarkable advantage of OTS, with substrate-free two-terminal structure, lies in its extremely high area utilization. Compared to MOSFET (> 8F2) and bipolar switches (5F2), the combination of OTS and PCM in a 1S1R configuration can achieve 4F2, which is a critical requirement for 3D high-density stacking-a key aspect of miniaturization. Over the past 20 years, PCM technology not only underwent aggressively size scaling from 180 nm to 20 nm, but also experienced a revolutionary evolution of the selector cell from the initial silicon-based MOSFET and bipolar junction transistor (BJT) to the OTS technology, successfully enabling the increasing capacity from 4 Mb to 256 Gb [11, 12, 25,26,27,28].

In 2009, Intel’s research team first reported the 1S1R 3D stacking technology [11] (Fig. 28a, b). In August 2015, Intel and Micron jointly announced the 3D Xpoint chip based on “bulk change” technology (a novel PCM device structure). In 2017, Intel introduced the Optane series chips based on 3D PCM technology to the market, including Optane solid-state drives (SSD) for the enterprise market and Optane flash memory for the consumer market. These chips were manufactured using mainstream 20-nm process technology, with a two-layer stacking. The optimized Ge–Se–As–Si OTS materials was believed to be used in the PCM-based Optane, achieving a storage density of 0.62 Gb mm−2 (Fig. 28c). This density was approximately 4.5 times higher than that of DRAM at the same 20-nm process node, with 91.4% of the core area occupied by the memory array [147]. In October 2019, Micron introduced the X100 NVMe enterprise SSD based on 3D PCM technology. Currently, 3D PCM with cross-point memory array has achieved four layers and 256 Gb per die in the second generation (Fig. 28d). The two generations of Intel’s Optane memory, which are based on the 3D Xpoint structure, are the outstanding application of OTS devices. Although the next generation of Optane memory will not be introduced in the short term due to commercial and market reasons, the successful commercialization of the two generations of Optane memory serves as strong evidence for the application of OTS devices in memory technology.

Process complexity and cost are the main factors behind the current suspension of 3D Xpoint business. Moreover, as the number of stacking layers continues to increase, the cost per bit will significantly increase rather than decrease, due to the high dependence on lithography. The persistently high cost issue will be one of the challenges that the 3D Xpoint structure will inevitably face in future [148]. Therefore, the concept of using vertically integrated “true” 3D structures for high-density storage is gradually gaining attention. Although there is currently no fixed standard for vertical memory architecture, we can be certain that in vertical structures similar to 3D NAND, OTS materials will continue to play a role as the “select layer” integrated with the memory cell [149, 150]. Furthermore, the OTS device can be applied not only to PCM but also to other emerging memories, like resistance random access memory (RRAM), and still holds great application prospects in 3D storage technology.

5.2 Self-Selecting Memory

As aforementioned, the 3D Xpoint structure will face increasing manufacturing costs as the number of layer increase (Fig. 29a) [148]. This issue could potentially be addressed by adopting vertical architecture. However, it is foreseeable that for the current 1S1R structure, there are inherent process difficulties in precisely controlling the composition and ensuring atomic-level homogeneity in the film. In addition, the traditional 1S1R structure requires a memory cell to be connected in series with an independent selector, resulting in a small overall aspect ratio, which will bring about process problems such as “leaning” involving the overall strength of the device as the process node scales down (Fig. 29b) [55, 152, 153]. To address these issues, a new technology path known as “self-selecting” has emerged, aiming to converge the selector and memory into a unit without the need for another separate device [154,155,156,157]. Memory devices based on this architecture are referred to as “self-selecting memory (SSM)” (Fig. 29c). This concept goes beyond the self-select of the memory cell in 0T1R structure and includes the implicit concept of self-memory in the 1T0S structure. To realize this technological concept, the measurable parameters used to represent the stored data must be designed to ensure the stability, repeatability, and a large enough difference between two (or more) states to enhance the data retention and maintain the access window.

The OTS selector, being typical volatile device, is impractical for storing data using the conventional binary on/off states. Interestingly, Vth in OTS selector were found to be influenced by many factors such as device structure variations, the amplitude of applied pulses [158], pulse width [159], ramp rate [160], and relaxation time [161]. Ravsher et al. in late 2021, observed the control of the Vth of OTS device (composed of Ge–Te–As–Si) by the polarity of the applied voltage, more specifically, a systematic and stable changed with the alterations in polarity of the applied voltage (Fig. 30) [145]. The value of Vth in the current operation was closely affected by the polarity of the previous pulse, resulting in the generation of two relatively stable Vth levels, Vth1 and Vth2, within the same pulse direction. In this work, the negative polarity Vth difference (ΔVth =|Vth1−Vth2|) was 260 mV, while the external resistance increased, further enhancing the ΔVth (Fig. 30c). Exploiting this stable ΔVth, which could persist for at least 1000 s (~ 17 min) as reported, enabled the independent utilization of OTS device for binary storage device, called OTS-only SSM.

Subsequently, the research team reported on the optimized device in mid-2022 [162], focusing on their application in the 1S1R structure. The device employed Ge–Se–As–Si OTS material. The improved device exhibited a further increase in the ΔVth, ~ 1 V, and the positive ΔVth became more pronounced. The SSM, which was in series with a Ge–Sb–Te PCM cell (Fig. 31a), aimed to enhance the performance of traditional 1S1R cell by offering double SET states and RESET states, each with a distinct difference. By employing voltage operation with different polarities, the originally small margin window (0.85 V) was effectively enlarged to ~ 1.7 and ~ 1.4 V. The 1S1R cell demonstrated a rather long retention reaching up to 1 month @ 25 °C (Fig. 31b) and an endurance over 108 cycles (Fig. 31c). Additionally, the significant difference among the four states indicated the potential for multi-level storage with four resistance states and even more (Fig. 31d). If the PCM itself has the potential to achieve multi-level storage, then the polarity operation of OTS devices may enable doubling of the storage states.

Ge–Se–As–Si 1S1R cell and SSM. a Structure of the 1S1R cell and the distribution of its margin window. b > 1-month Retention. c Endurance over 108 cycles. d Four storage levels induced by the polarity effect. Adapted with permission from [162]. Copyright 2022, IEEE. e SSM with 75 nm feature size. f I–V curves and the distribution of negative and positive ΔVth [162, 163]. g Endurance characteristics under bipolar stress. h Retention measurement. Adapted with permission from [163]. Copyright 2023, IEEE

Recently, Ge–Se–As–Si-based SSM device with C-based electrodes was reported by the same research team [163]. The device exhibited a larger positive ΔVth of ~ 0.9 V and negative ΔVth of ~ 1.3 V (Fig. 31f), an ultralow writing current < 15 µA and a high endurance > 108 cycles (Fig. 31g). However, the SSM device showed some limitations in data retention. With a write operation performed at 75 μA, the window could be reliably maintained for 1 month @ 25 °C (Fig. 31h), and nearly disappeared after five months. If a lower operating current ~ 15 μA was employed, the data retention of the device further decreased to ~ 10 days, indicating that the SSM device cannot currently be considered a typical non-volatile memory without compositional and structural optimizations. However, it can be utilized as a “DRAM-like” memory with a longer refresh period, and the non-destructive “Read” operation can be used for refresh operation.

In 2022, Hong et al. [151] from SK Hynix fabricated a prototype of a 32 Mb SSM (Fig. 32a), strongly confirming the feasibility of engineering SSM for practical applications. The simplified device structure provided a larger aspect ratio, enabling it to maintain a good switching window even at the 15-nm process node (Fig. 32b). The device exhibited high endurance exceeding 107 cycles (Fig. 32c) and a rather low Iop (Fig. 32e). The unique structure of the SSM effectively suppressed the increasingly significant thermal disturbance in downscaled PCM (Fig. 32d). Through four generations of product iterations, the margin window of the prototype has slightly surpassed that of PCM in 3D Xpoint (Fig. 32f).

SSM prototype. a Structure of the SSM array. b Variations of Vth and the memory window with the device scaling down. c Endurance and the distribution of Vth. d Distribution of Vth before and after the driven thermal disturbance. e Vth–I curves between 3D Xpoint and SSM. f Comparison of the margin window with 3D Xpoint [151]. Adapted with permission from [151]. Copyright 2022, IEEE

In summary, the innovative SSM technology offers a promising path for future application of the OTS device. Additionally, the endurance of OTS devices, resulting from their switching behavior, replaces the repetitive amorphous–crystalline phase transition in PCM, leading to significantly improve the endurance. Furthermore, the use of OTS device’s threshold current/voltage instead of PCM’s operating current/voltage eliminates the need for melting the chalcogenide material, resulting in a notable reduction in energy consumption.

5.3 Neuromorphic Computing

In the traditional von Neumann architecture, which separates storage and computation, there is an inherent “memory wall” problem, which becomes more pronounced as the process node scales down [5, 164]. With the recent resurgence of AI technologies, a series of bio-inspired neural computing architectures have gathered significant attention due to their potential for achieving ultra-low power consumption and large-scale, highly parallel and high-speed computing. The neural computing platform and its devices, as the physical embodiments of these neural computing architectures, have naturally become a focal point of research. The physical realization of artificial neurons, synapses, and other bio-inspired devices is one of the key challenges in neuromorphic computing [165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172]. Mainstream novel computing architectures include spiking neural networks (SNNs), deep neural networks (DNNs), and in-memory computing. For a long time, the physical implementation of these computing architectures relied on combinations of CMOS and non-volatile memory (e.g., PCM, RRAM) [165,166,167,168, 173,174,175]. Early on, OTS played a role as a selector, primarily in combination with the memory, to suppress leakage currents, reduce power consumption, and restrain crosstalk, which is particularly crucial in large-scale arrays [146]. However, selector unit did not directly serve as artificial neurons and synapses themselves at that time.

The spiking neural networks exhibit remarkable potential in reducing the computational energy consumption due to their event-based and data-driven nature. However, the lack of a general learning rule hampers their ability to construct the large-scale networks. Recent reports suggest that SNNs can be constructed by transforming pre-trained artificial neural networks (ANNs). In this transformation, the neuron units are simplified to integrate and fire (I&F) neurons, which integrate input synaptic current and charge the membrane potential [176,177,178,179]. Once the membrane potential reaches the threshold voltage, the neuron generates spikes to the next synapse layer and resets the membrane potential. This characteristic aligns well with threshold switching devices [169], as traditional CMOS-based neurons suffer from large size and high power consumption [180,181,182,183].

Hence, the selectors, including NbO2-based MIT devices, B–Te-based OTS devices, and Ag/HfO2-based ionic-diffusion devices, have been investigated by Lee et al. as potential components for I&F neurons [184]. The study revealed that the B–Te OTS device exhibited excellent comprehensive performance, showcasing a low Ioff of ~ 5 nA (Fig. 33d) and a short switching time of < 10 μs. These features contribute to improved leakage behavior and signal responsiveness in the operation of I&F neurons based on B–Te OTS devices. The relationship between the output pulse count and input current of the B–Te OTS device followed a typical rectified linear unit (ReLU) function (Fig. 33e). Additionally, the device demonstrated a higher operating bandwidth and more stable response characteristics in the relationship between output pulse count and input signal frequency tests (Fig. 33f). Remarkably, the B–Te OTS device also exhibited outstanding energy efficiency, with power consumption reducing to 30 pJ per spike. Subsequently, the research team employed I&F neurons based on B–Te OTS devices to process frequency-encoded ANN data in an SNN for handwritten recognition tests, achieving an acceptable recognition rate ~ 33% (Fig. 33g).

Integrate and fire (I&F) neuron based on B–Te. a Concept of integrate and fire (I&F) neuron. b Schematic and Operation principle of I&F neuron. c V–t curves of neurons based on B–Te under different input current. d I–V curves of B-Te; e Number of spikes versus input current amplitude in B–Te selector, indicating the typical ReLU function. f Number of spikes as a function of pulse interval. g MNIST classification and the result of recognition [66, 184]. Adapted with permission from [184]. Copyright 2019, John Wiley and Sons