Abstract

Purpose of Review

While living organ donor follow-up is mandated for 2 years in the USA, formal guidance on recovering associated costs of follow-up care is lacking. In this review, we discuss current billing practices of transplant programs for living kidney donor follow-up, and propose future directions for managing follow-up costs and supporting cost neutrality in donor care.

Recent Findings

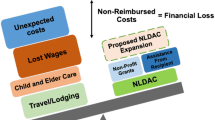

Living donors may incur costs and financial risks in the donation process, including travel, lost time from work, and dependent care. In addition, adherence to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) mandate for US transplant programs to submit 6-, 12-, and 24-month postdonation follow-up data to the national registry may incur out-of-pocket medical costs for donors. Notably, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has explicitly disallowed transplant programs to bill routine, mandated follow-up costs to the organ acquisition cost center or to the recipient’s Medicare insurance. We conducted a survey of transplant staff in the USA (distributed October 22, 2020–March 15, 2021), which identified that the mechanisms for recovering or covering the costs of mandated routine postdonation follow-up at responding programs commonly include billing recipients’ private insurance (40%), while 41% bill recipients’ Medicare insurance. Many programs reported utilizing institutional allowancing (up to 50%), and some programs billed the organ acquisition cost center (25%). A small percentage (11%) reported billing donors or donors’ insurance.

Summary

To maintain a high level of adherence to living donor follow-up without financially burdening donors, up-to-date resources are needed on handling routine donor follow-up costs in ways that are policy-compliant and effective for donors and programs. Development of a government-supported national living donor follow-up registry like the Living Donor Collective may provide solutions for aspects of postdonation follow-up, but requires transplant program commitment to register donors and donor candidates as well as donor engagement with follow-up outreach contacts after donation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Living donor kidney transplantation not only offers the best treatment option to patients in need of renal replacement therapy but also provides cost-savings to the healthcare system, compared to both dialysis and deceased donor transplantation. A contemporary discrete event model analysis of a hypothetical cohort of 20,000 end-stage renal disease patients found that almost all living donor kidney transplants result in cost savings, ranging from $13,000 USD to $30,000 USD, and even higher risk transplants from HLA-incompatible donors were cost-effective [33].

Some transplant programs may have misinterpreted the CMS manual and sought to recover LKD follow-up care costs via the MCR or recipient Medicare billing to fulfill the OPTN mandate and recover associated costs. Billing the recipient’s Medicare and using the MCR tend to occur more at smaller compared to larger volume programs, and at centers with lower vs. higher baseline follow-up performance. Thus, broader-reaching education for transplant programs is needed on billing practices that are compliant with the CMS manual. We recently outlined appropriate mechanisms for recovery of follow-up care costs [34], which include (1) billing recipient non-Medicare insurance unless excluded in the insurer's contract, (2) covering costs with institutional or charitable funds [33, 35], (3) allowancing or writing-off at the transplant center level, and (4) billing donors or donor insurance (for services either at the transplant program or at a primary care physician’s office).

Future Directions for Managing Living Donor Follow-up Costs

Living donor candidates must be counseled in detail about the potential financial consequences of donation during the evaluation. Failing to counsel appropriately on financial risks may compromise the ability of donor candidates to provide informed consent. Living donors should also be educated on and assisted in accessing reimbursement programs for donation-associated costs, such as the US federally-funded Living Donor Assistance Center (NDLAC), and the National Kidney Registry’s “Living Donor Shield” when applicable [36, 37]. We also contend that universal access to living donor follow-up is important in the first few years to monitor health and to instill in donors the value of engaging in long-term routine screening. As such, there is a rationale to include living donor follow-up care as a covered benefit under OACC. Uniform access to follow-up care is especially important in the USA, where there are significant disparities in access to healthcare and living donor outcomes based on social determinants of health and other factors [14]. Provision of donor follow-up care may also reduce financial burdens on donors, and provide early warning systems for donors at increased risk of long-term complications [38].

We also support the concept of national tracking of donor outcomes and posit that gaps in funding mechanisms may limit such efforts in the USA. Successful models to acquire information on living donor outcomes exist elsewhere, particularly in countries with socialized medicine. For example, all living donors in Switzerland are registered in the Swiss Organ Living Donor Health Registry, which collects information from general practitioners at 1-year after donation and biennially thereafter [39]. Australia and New Zealand have a similar universal system [40]. In the USA, the Living Donor Collective is a Health Services Research Administration (HRSA)-supported initiative of the SRTR to create a lifetime registry for all donor candidates evaluated at US transplant centers [41, 42], for which pilot phase experience (June 2018–September 2020) was recently published [43]. Under the Living Donor Collective model, centers register donor candidates, and the SRTR is responsible for follow-up. Development of a government-supported national living donor follow-up registry like the Living Donor Collective may provide solutions for aspects of postdonation follow-up, but requires transplant program commitment to register donors and donor candidates, as well as donor engagement with follow-up outreach contacts after donation.

Conclusion

A path towards mitigating health and financial risks of living kidney donation includes maintaining a high level of adherence to complete living donor follow-up without financially burdening donors. We advocate for the revision of OACC policy to include follow-up costs as part of the commitment necessary for living donor care and safety, rather than solely for data collection. The SRTR Living Donor Collective may also provide a solution for long-term follow-up [41, 42], but requires a partnership of transplant centers in registering donors and donor engagement to be successful. Ongoing efforts to support follow-up for all living donors, including attention to covering necessary costs and removing financial barriers, are vital to help ensure opportunities for safe donation, especially among vulnerable groups.

Data Availability

Data availability is limited to aggregate summaries as reported, based on IRB requirements.

References

Axelrod DA, Schnitzler MA, **ao H, et al. An economic assessment of contemporary kidney transplant practice. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(5):1168–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.14702.

LaPointe RD, Hays R, Baliga P, et al. Consensus conference on best practices in live kidney donation: recommendations to optimize education, access, and care. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(4):914–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.13173.

Tushla L, Rudow DL, Milton J, et al. Living-donor kidney transplantation: reducing financial barriers to live kidney donation–recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(9):1696–702. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.01000115.

Lentine KL, Mannon RB, Mandelbrot D. Understanding and overcoming financial risks for living organ donors. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;79(2):159–61. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.09.003.

Leichtman A, Abecassis M, Barr M, et al. Living kidney donor follow-up: state-of-the-art and future directions, conference summary and recommendations. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(12):2561–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03816.x.

Lam NN, Lentine KL, Levey AS, Kasiske BL, Garg AX. Long-term medical risks to the living kidney donor. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11(7):411–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2015.58.

Lentine KL, Segev DL. Understanding and communicating medical risks for living kidney donors: a matter of perspective. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(1):12–24. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2016050571.

Lentine KL, Lam NN, Segev DL. Risks of living kidney donation: current state of knowledge on outcomes important to donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(4):597–608. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.11220918.

Ommen ES, Winston JA, Murphy B. 2006 Medical risks in living kidney donors: absence of proof is not proof of absence. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1(4):885–95. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.00840306.

Lentine KL, Patel A. Risks and outcomes of living donation. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2012;19(4):220–8. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2011.09.005.

Lentine KL, Segev DL. Health outcomes among non-Caucasian living kidney donors knowns and unknowns. Transpl Int. 2013;26(9):853–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/tri.12088.

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). Procedures to collect post-donation follow-up data from living donors. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/resources/guidance/procedures-to-collect-post-donation-follow-up-data-from-living-donors/. Accessed 09/07/2022.

OPTN (Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network)/UNOS (United Network for Organ Sharing). OPTN policies, Policy 18: data submission requirements. http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/governance/policies/ . Accessed 09/07/2022.

Lam NN, Muiru AN, Tietjen A, et al. Associations of lack of insurance and other sociodemographic traits with follow-up after living kidney donation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.01.427.

Fu R, Sekercioglu N, Hishida M, Coyte PC. Economic consequences of adult living kidney donation: a systematic review. Value Health. 2021;24(4):592–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2020.10.005.

Park S, Park J, Kang E, et al. Economic impact of donating a kidney on living donors: a Korean cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 2022;79(2):175-184 e1. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.07.009

Ruck JM, Holscher CM, Purnell TS, Massie AB, Henderson ML, Segev DL. Factors associated with perceived donation-related financial burden among living kidney donors. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(3):715–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.14548.

Larson DB, Wiseman JF, Vock DM, et al. Financial burden associated with time to return to work after living kidney donation. Am J Transplant. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.14949.

Yang RC, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Klarenbach S, Vlaicu S, Garg AX. Insurability of living organ donors: a systematic review. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(6):1542–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01793.x.

Yang RC, Young A, Nevis IF, et al. Life insurance for living kidney donors: a Canadian undercover investigation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(7):1585–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02679.x.

Boyarsky BJ, Massie AB, Alejo JL, et al. Experiences obtaining insurance after live kidney donation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(9):2168–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.12819.

Lapointe Rudow D, Cohen D. Practical approaches to mitigating economic barriers to living kidney donation for patients and programs. Curr Transpl Rep. 2017;4:24–31.

Tushla L, Rudow DL, Milton J, Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Hays R. Living-donor kidney transplantation: reducing financial barriers to live kidney donation–recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(9):1696–702. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.01000115.

Lentine KL, Mannon RB, Mandelbrot D. Understanding and overcoming financial risks for living organ donors. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;79(2):159–61. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.09.003.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS Provider Reimbursement Manual; Chapter 31; Section 3106; page 10. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Paper-Based-Manuals-Items/CMS021929. Accessed 09/07/2022.

Doshi MD, Singh N, Hippen BE, et al. Transplant clinician opinions on use of race in the estimation of glomerular filtration rate. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16(10):1552–9. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.05490421.

Lentine KL, Motter JD, Henderson ML, et al. Care of international living kidney donor candidates in the United States: a survey of contemporary experience, practice, and challenges [published online October 19, 2020]. Clin Transplant 2020;34(11). https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.14064.

Lentine KL, Peipert JD, Alhamad T, et al. Survey of clinician opinions on kidney transplantation from hepatitis C virus positive donors: identifying and overcoming barriers. Kidney 360. 2020;1(11):1291–9. https://doi.org/10.34067/KID.0004592020.

Lentine KL, Vest LS, Schnitzler MA, et al. Survey of US living kidney donation and transplantation practices in the COVID-19 era. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(11):1894–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2020.08.017.

Alhamad T, Lubetzky M, Lentine KL, et al. Kidney recipients with allograft failure, transition of kidney care (KRAFT): a survey of contemporary practices of transplant providers. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(9):3034–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.16523.

Mandelbrot DA, Pavlakis M, Karp SJ, Johnson SR, Hanto DW, Rodrigue JR. Practices and barriers in long-term living kidney donor follow-up: a survey of U.S. transplant centers. Transplantation. 2009;88(7):855–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0b013e3181b6dfb9.

Waterman AD, Dew MA, Davis CL, et al. Living-donor follow-up attitudes and practices in U S. kidney and liver donor programs. Transplantation. 2013;95(6):883–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0b013e31828279fd.

Kulkarni S, Thiessen C, Formica RN, Schilsky M, Mulligan D, D’Aquila R. The long-term follow-up and support for living organ donors: a center-based initiative founded on develo** a community of living donors. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(12):3385–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.14005.

Tietjen A, Hays R, McNatt G, et al. Billing for living kidney donor care: balancing cost recovery, regulatory compliance, and minimized donor burden. Curr Transpl Rep 2019;6(2):155–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40472-019-00239-0.

Keshvani N, Feurer I, Rumbaugh E, et al. Evaluating the impact of performance improvement initiatives on transplant center reporting compliance and patient follow-up after living kidney donation. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(8):2126–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.13265.

Lentine KL, Mannon RB. The Advancing American Kidney Health (AAKH) executive order: promise and caveats for expanding access to kidney transplantation. Kidney. 2020;1(6):557–60. https://doi.org/10.34067/KID.0001172020.

Garg N, Waterman AD, Ranasinghe O, et al. Wages, travel and lodging reimbursement by the National Kidney Registry: an important step towards financial neutrality for living kidney donors in the United States. Transplantation. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000003721.

Kasiske BL, Anderson-Haag T, Israni AK, et al. A prospective controlled study of living kidney donors: three-year follow-up. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(1):114–24. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.019.

Thiel GT, Nolte C, Tsinalis D. Prospective Swiss cohort study of living-kidney donors: study protocol. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2):e000202. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000202.

Clayton PA, Saunders JR, McDonald SP, et al. Risk-factor profile of living kidney donors: The Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Living Kidney Donor Registry 2004–2012. Transplantation. 2016;100(6):1278–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000000877.

Kasiske BL, Asrani SK, Dew MA, et al. The living donor collective: a scientific registry for living donors. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(12):3040–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.14365.

Kasiske BL, Ahn YS, Conboy M, et al. Outcomes of living kidney donor candidate evaluations in the Living Donor Collective Pilot Registry. Transplant Direct. 2021;7(5):e689. https://doi.org/10.1097/TXD.0000000000001143.

Kasiske BL, Lentine KL, Ahn Y, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2020 Annual data report: living donor collective. Am J Transplant. 2022;22(Suppl 2):553–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.16983.

OPTN Policies, Policy 18.5: Data submission requirements. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/eavh5bf3/optn_policies.pdf Accessed 09/07/2022.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following:

• Survey respondents, including members of the American Society of Transplantation (AST) Living Donor Community of Practice (LDCOP) and the Transplant Administrators and Quality Management (TxAQM) COP for review of the survey instrument and sharing the survey link on community Hubs.

• The AST Education Committee for review and feedback on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

DISCLOSURES

KLL is a Senior Scientist of the SRTR, receives research funding related to living donation from the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01DK120551), and is also supported by the Mid-America Transplant/Jane A. Beckman Endowed Chair in Transplantation. The authors are volunteer members of the AST LDCOP and TxAQM COP Financial Workgroup, chaired by TA. KLL is chair of the AST LDCOP, member of the ASN Policy and Advocacy Committee, and a member of the NKF Transplant Advisory Committee. Unrelated to this work, KLL receives consulting fees from CareDx and speaker honoraria from Sanofi.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Krista L. Lentine and Nagaraju Sarabu are co first-authors.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Live Kidney Donation.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lentine, K.L., Sarabu, N., McNatt, G. et al. Managing the Costs of Routine Follow-up Care After Living Kidney Donation: a Review and Survey of Contemporary Experience, Practices, and Challenges. Curr Transpl Rep 9, 328–335 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40472-022-00379-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40472-022-00379-w