Abstract

Background

Mailed stool testing programs increase colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in diverse settings, but whether uptake differs by key demographic characteristics is not well-studied and has health equity implications.

Objective

To examine the uptake and equity of the first cycle of a mailed stool test program implemented over a 3-year period in a Central Texas Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) system.

Design

Retrospective cohort study within a single-arm intervention.

Participants

Patients in an FQHC aged 50–75 at average CRC risk identified through electronic health records (EHR) as not being up to date with screening.

Interventions

Mailed outreach in English/Spanish included an introductory letter, free-of-charge fecal immunochemical test (FIT), and lab requisition with postage-paid mailer, simple instructions, and a medical records update postcard. Patients were asked to complete the FIT or postcard reporting recent screening. One text and one letter reminded non-responders. A bilingual patient navigator guided those with positive FIT toward colonoscopy.

Main Measures

Proportions of patients completing mailed FIT in response to initial cycle of outreach and proportion of those with positive FIT completing colonoscopy; comparison of whether proportions varied by demographics and insurance status obtained from the EHR.

Key Results

Over 3 years, 33,606 patients received an initial cycle of outreach. Overall, 19.9% (n = 6672) completed at least one mailed FIT, 5.6% (n = 374) tested positive during that initial cycle, and 72.5% (n = 271 of 374) of those with positive FIT completed a colonoscopy. Hispanic/Latinx, Spanish-speaking, and uninsured patients were more likely to complete mailed FIT compared with white, English-speaking, and commercially insured patients. Spanish-speaking patients were more likely to complete colonoscopy after positive FIT compared with English-speaking patients.

Conclusions

Mailed FIT outreach with patient navigation implemented in an FQHC system was effective in equitably reaching patients not up to date for CRC screening.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening is effective but underutilized. Recent data from the CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) show that only 71.6% of adults 50–75 are up to date with screening based on any of the recommended modalities, with important variation by state.1,2,3 CRC screening occurs at lower levels in those with less education, income, or English proficiency; those without health insurance; and in those identifying as Hispanic or Latino.1,3,4 Reaching national targets for CRC screening, including the HealthyPeople 2030 goal of 74.4% up to date, will require robust efforts to improve screening and reduce disparities in screening.5 Multiple interventions have been shown to increase screening but have not been broadly implemented.6,7 In choosing interventions, clinicians and policymakers must balance effectiveness and feasibility while also seeking interventions that reduce rather than exacerbate screening disparities.

One promising setting for interventions to improve CRC screening and screening equity is the large network of Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs). FQHCs serve disadvantaged and diverse populations, hence representing a site for interventions to improve screening equity. Currently, however, FQHC CRC screening levels are notably lower than national and state averages: as of 2020, only 40% of FQHC patients nationally are up to date and just 34% in Texas.8,9 As such, raising screening rates in FQHCs presents a strong opportunity for improving screening equity. However, FQHCs are generally under-resourced and face many competing demands; interventions to improve CRC screening must be implemented in a way that strengthens rather than depletes resources within such systems.10

Mailed fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) is one effective and efficient means of increasing CRC screening, including for under-resourced settings like FQHCs. Mailed FIT programs have led to completion of CRC screening in 20–30% of unselected, age-eligible patients, including in FQHC and safety net systems.6,7,11 Mailed FIT has several advantages: it is convenient because it is performed by the patient at home, has low initial testing cost, conserves colonoscopy resources, is scalable, and frees face-to-face visit time, thus complementing in-clinic improvement efforts.7

To be effective, however, FIT-based screening programs must not only increase initial test completion, but also ensure that those who test positive undergo timely follow-up colonoscopy to detect and remove pre-cancerous polyps, identify early-stage cancers for curative treatment, and decrease mortality.12 Ensuring high follow-up levels can be particularly challenging in vulnerable patients who may face challenges related to transportation; access to affordable, safe, high-quality colonoscopy; and interactions with health care systems that do not always address language or literacy barriers to care. A number of studies have examined interventions to improve follow-up, including ones specific to vulnerable patients.13,14,15 Perhaps the most effective programs include patient navigation, with a trained navigator assisting the patient in scheduling, preparing for, attending, and following up after colonoscopy.

We and others have shown that mailed FIT programs are cost-effective, even accounting for the resources required to reach vulnerable patients and ensure appropriate follow-up.14,16,17 Program costs are offset by cost savings from preventing cancers and cancer deaths.14 These findings have been generated in a wide range of systems, including safety net practices.7,17

Given these advantages, implementing mailed FIT appears to be a promising method for improving screening and screening health equity, but it is important to confirm that implementation improves, or at least does not exacerbate, screening disparities. Thus, we sought to measure uptake of a mailed FIT program and appropriate follow-up in a safety net setting and to evaluate whether the uptake and follow-up differ by key demographic characteristics, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, language, and insurance status, in order to ensure that the mailed FIT program is not exacerbating — and hopefully improving — screening disparities.

METHODS

Design

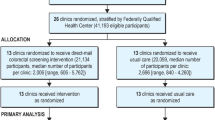

We performed a retrospective cohort study within a single-arm intervention. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas at Austin reviewed this protocol and determined it to be non-human subjects research, categorized as a quality improvement project.

Setting and Participants

We examined a mailed FIT program in a large, urban Texas FQHC system from November 2017 to February 2021. This system’s colorectal cancer screening level (proportion of patients up to date) before implementation of the mailed FIT program was 18.6% in 2017.

We identified age-eligible patients ages 50–75 from the EHR. Patient selection criteria included having no evidence of recent screening based on USPSTF criteria, not being clearly at high risk (based on the diagnosis code for personal history of colorectal cancer), and having been seen at least once in the past 12 months or twice during the past 24 months in the FQHC. The eligible cohort was dynamic: patients entered and left eligibility based on these criteria on a monthly basis over the program. A small number of patients over age 75 were included inadvertently and have been retained in this report.

We report here on the effects of the first cycle of mailed intervention to eligible patients. The program was designed so that those who responded to the first year intervention would receive subsequent mailings annually, approximately 12 months from completion of the prior test. Adherence to subsequent annual mailings will be reported in a future manuscript.

Screening Program

The program team sent outreach packets written in both English and Spanish on a rolling basis, with groups of packets mailed typically on a weekly basis, avoiding holidays. The packets contained an introductory letter with information about screening (see ESM Appendix), the FIT kit with lab requisition form, pictorial instructions for FIT completion, and a prepaid mailer to send the completed kit directly to the lab for analysis. Materials were designed to be readable at the 6th grade reading level and adhered to key principles of literacy-sensitive design. The introductory letter made clear that the FIT would be processed without any cost to the patient and that follow-up colonoscopy would be performed without charge for uninsured patients. The packet also contained a foldable records postcard, which the patient could send back with details if they were already up to date on screening. Patients also had the option to opt out of future outreach related to this program.

If the patient did not complete the test or return the records postcard, a text message reminder was sent 3 weeks after the initial mailing, and a letter reminder was sent 5 weeks after the initial mailing.

Negative FIT results were recorded in the EHR lab results section and communicated to the patient via letter by the program.

Positive FIT Follow-up and Navigation to Colonoscopy

Positive FIT results were returned to the screening program and also communicated to the physician in the EHR, and a bilingual patient navigator notified patients of the positive result via telephone. The bilingual patient navigator helped patients with a positive FIT on the path to complete a follow-up colonoscopy, building patient self-efficacy and confidence, overcoming fears, and providing a referral to a faculty gastroenterologist embedded within the FQHC system, at which point the patient completed a pre-procedure evaluation. At that evaluation appointment, patients received instructions on how to complete the colonoscopy prep; however, the navigator also followed up to ensure the patient understood the process and provided further explanation as needed. The navigator confirmed that the patient had an appointment for the colonoscopy and would facilitate re-scheduling if needed. The navigator addressed patient barriers; alleviated concerns about test results, prep, or procedures; and helped with any required follow-up after the colonoscopy. Most colonoscopies were completed by faculty gastroenterologists practicing in a hospital-based endoscopy suite. The program navigator communicated with endoscopy facilities and with the patients to help obtain record of the colonoscopy results, including pathology.

Data Management

A secure database was maintained in REDCap to organize patient information, FIT mailing, FIT completion, follow-up colonoscopy completion, and colonoscopy results. We used program data through September 24, 2021 (6 months from the date of the last mailing) to assess outcomes.

Statistical Analyses

We assessed the proportion of patients completing mailed FIT as a result of the first year cycle of intervention and the proportion of patients who completed a follow-up colonoscopy in response to positive FIT in the initial cycle of outreach. We compared whether these proportions varied based on patient demographics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, preferred language) and insurance status obtained from the EHR. We calculated bivariate odds ratios of mailed FIT completion with 95% confidence intervals using the following reference groups: age less than 60 years; male for gender; white, non-Hispanic for race/ethnicity; English for language; and commercial insurance for payer.

To understand differences by demographic characteristics in the proportion of patients completing colonoscopy after a positive FIT, we used chi-square tests to examine differences in any colonoscopy completion after positive FIT and completion of colonoscopy within 90 days of the positive FIT. We also examined median time to colonoscopy completion and whether it differed by demographic characteristics, using Mood’s median test. Because we found similar patterns as the analyses examining proportion ever completing or completing within 90 days, we do not present the differences in median time here.

All statistical analyses were performed using R statistics software.18

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

There were 33,606 patients who were eligible and received mailed FIT outreach during the study period (Table 1). As demonstrated in the table, the program population was diverse in terms of race/ethnicity, primary language, and insurance status.

During the program period studied, 1037 patients returned the records update postcard. Of these, 810 (78.1%) included information on screening status, with 292 indicating recent FOBT screening and 546 indicating a previous colonoscopy (36 patients documented both). Of the returned cards, 217 patients opted out of future contact, although 17% of those patients also completed a FIT and 81% provided updated screening information on the same returned card. Of the 33,606 participants, 1715 (5.1%) had their packet returned as “undeliverable” and could not be reached subsequently.

Overall Results

Overall, 6672 patients (19.9%) completed at a mailed FIT during the study period. Of these 6672 patients, 374 (5.6%) had a positive result. Of the 6672 respondents, 4616 responded to the initial mailing only, 356 after the text reminder but before a letter reminder, and 1700 after the letter reminder.

Differences in Mailed FIT Completion by Demographics

Based upon the percentages completing mailed FIT within each grou**, completion was similar without large absolute differences by any of the demographic characteristics (Table 2). Those aged 60–69, female, Hispanic/Latinx, Other/Multiracial non-Hispanic, patients not speaking English as their primary language, and patients who were uninsured or on sliding scale payment had modestly higher odds of completion than other groups (Table 2).

Follow-up Colonoscopy After Positive FIT

Of 374 patients with positive FIT in the first cycle of screening, 271 (72.5%) completed a follow-up colonoscopy at any subsequent time and just under half (49.7%) completed within 90 days of the positive FIT. Of the 271 who completed any colonoscopy, median time to completion was 55 days.

Demographics of Completion of Colonoscopy After Positive FIT

We found higher colonoscopy completion rates among Spanish-speaking patients and among younger patients (50–59) compared with older patients (Table 3).

Distribution of Findings on Colonoscopy

Of the 271 patients who completed colonoscopy after positive FIT, 9 patients had colorectal cancer, 117 patients (43.1%) had one or more adenomas, and 12 had hyperplastic polyps. Among the 117 with one or more adenomas, 37 were labeled as low-risk and 80 as high-risk.

DISCUSSION

We found that a mailed intervention implemented in a large FQHC with no-cost FIT, easy-to-read, literacy-sensitive instructions, a convenient method of postage-free return mailing, and access to a bilingual patient navigator led to approximately 20% of patients completing FIT with over 70% of those testing positive going on to successful follow-up colonoscopy. Notably, the program was successful in reaching a diverse patient population in a relatively equitable manner: Hispanic/Latinx, Spanish-speaking, and uninsured patients, who have traditionally been less likely to be screened, were somewhat more likely to complete mailed FIT compared with white, English-speaking, and commercially insured patients, respectively. We also observed similar equitable findings for successful completion of colonoscopy after positive FIT, albeit with a smaller sample size. These findings obtained in a diverse patient population suggest that such an intervention may be an important strategy for promoting screening equity and hence reducing disparities in colorectal cancer screening and outcomes.

There are several potential reasons why this intervention may have been effective in ensuring equitable uptake within this FQHC population. One contributing factor may be that the mailed FIT program was implemented without direct cost to participants, which may have encouraged completion among groups with low income and who lacked traditional health insurance. Moreover, literacy-sensitive materials provided in English and Spanish and availability of a bilingual navigator helped overcome language barriers that may contribute to lower completion rates among those speaking Spanish in the general populace. The program also provided financial support for uninsured patients to receive follow-up colonoscopy, removing an important barrier to successful follow-up testing.

Mailed colorectal cancer screening programs implemented in other FQHCs, safety net settings, or clinics serving underinsured/uninsured patients have achieved similar 17–36% completion of mailed FIT or FOBT using similar types of intervention, including literacy-sensitive brochures and instructions and mailed or texted reminders to accompany FIT.6,11,14,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30 Some of these programs also offered phone calls or patient navigation for completion of mailed FIT, a more expensive intervention, and hence are not wholly comparable to our intervention. Notably, several interventions occurred in integrated safety net health care systems or non-FQHC commercially insured populations.24,31

A handful of studies have assessed mailed CRC screening by demographic factors, with no discernible patterns in differences in completion.14,21,22,26,30 Our work in assessing completion by demographic factors helps build out this facet of the literature on equitable implementation of mailed CRC screening. In our population, the mailed FIT screening was completed more often by Hispanic/Latinx, Spanish-speaking, and uninsured populations — populations whose screening rates in national samples tend to be significantly lower than the national average,32 although they represent a large proportion of the patients in this FQHC system.

While achieving high participation for FIT completion is important, the success of FIT-based screening programs also depends on high levels of colonoscopy completion after positive FIT. In previously published mailed FIT program evaluations, successful completion of colonoscopy after positive FIT ranged from 33 to 58% in similar settings, usually defined by completion within 6 or 12 months.15,33,34,35,36,37,38,39 Our program’s 72.5% colonoscopy completion after positive FIT (49.9% within 90 days) is higher than in many FQHC and safety net settings, in large part because of intensive, language-concordant patient navigation, a key feature of our program and one of the proven effective strategies for increasing completion.13 The availability of funding for colonoscopy for uninsured patients was also an important factor.

Similarly to our study, multiple programs examining differences in colonoscopy completion after positive FIT by demographic factors have found that patients not speaking English as a primary language tend to complete colonoscopy at higher rates than those speaking English as a primary language.34,35,37 In contrast, some studies have found that Hispanic patients are less likely to complete colonoscopy after positive FIT, suggesting the importance of viewing language and ethnicity as separate factors.36,39 More recent studies have found mixed effects with respect to race/ethnicity. 40,41,42 In our study, Spanish as the patient’s primary language was associated with higher rates of colonoscopy after positive FIT. Further investigation of promoting and limiting factors to colonoscopy may provide insight into these trends, though it is likely that our bilingual (English/Spanish) patient navigator role contributed to our program’s success.

Our intervention took place in an independent FQHC system with varied funding sources and thus differed from integrated health system settings; since Texas has not expanded Medicaid, many patients in the system were uninsured and fell into a self-pay sliding scale or received basic coverage through the county-level Medical Access Program (MAP). Our study is one of few looking into completion by demographic categories in FQHC and safety net settings to identify whether there are inequities in mailed FIT completion.14,21,22,26,30 In moving from positive FIT to colonoscopy, our program relied on a bilingual patient navigator who communicated the positive result to patients, helped set up gastroenterology and colonoscopy appointments as needed, and helped patients overcome any specific barriers to colonoscopy completion. Since our mailed FIT program existed in a non-integrated, multi-system care environment, navigation played a particularly important role in care coordination.

Now that we have quantified the performance of the mailed FIT program, we will perform qualitative analysis via patient interviews to assess barriers and promoting factors to FIT completion, as well as to assess patient attitudes toward mailed screening tests. In particular, we will investigate the impact of COVID on the propensity to complete mailed FIT and we will examine the social network effects on completion — for example, whether family members are more likely to complete screening together. Our analyses also suggest that the mailed FIT program may need increased targeting to patients under age 60 and males. Further investigation is also required to better understand why older adults had lower colonoscopy follow-up after positive FIT. Since the mailed FIT program has now been expanded to a second, more rural FQHC population, and to 45- to 49-year-olds in accordance with the May 2021 US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, we will look into the data to ensure there are no differential effects in these groups as the program continues into the future.

Our study has some limitations. First, because we chose to conduct a pragmatic program evaluation and because prior trials had already shown efficacy of mailed FIT, we did not conduct a controlled trial. As such, we are unable to assess whether these patients would have completed colorectal cancer screening in the absence of receiving mailed FIT. However, our study design’s lack of pre-selection allows approximation of what FIT completion looks like among all eligible patients in the real-world FQHC population. Secondly, we relied on EHR records for our demographic variables. EHR demographic data may not be fully accurate compared with self-report, especially for race/ethnicity and preferred language. Third, our program was implemented in a large, urban setting in Central Texas. Our findings may not be applicable in other settings, although the nature of the mailed intervention makes it particularly well-suited for rural settings. Fourth, our materials were designed to reach English- and Spanish-speaking patients; those whose preferred language was not English or Spanish may not have been reached as effectively, but our sample is too small to adequately assess that concern. Fifth, the mailed nature of the intervention meant that those patients with no or frequently changing addresses may not have been effectively reached. Finally, the screening rate in this FQHC prior to the intervention was 18.6%. Settings whose starting screening rate differs from the FQHC system in this study may see different uptake of a mailed FIT program, although our results are within the range observed in other real-world mailed FIT implementations and were accomplished at a reasonable cost per patient screened.7,17

To summarize, mailed FIT outreach was effective in reaching approximately 20% of patients who were not up to date with colorectal cancer screening and did so in a manner that improved screening equity, including successful follow-up of positive tests. Mailed FIT can be an important part of a comprehensive strategy to improve CRC screening and reduce CRC incidence and mortality while also improving health equity.

References

American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection: Facts & Figures 2021-2022. Available at: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-prevention-and-early-detection-facts-and-figures/2021-cancer-prevention-and-early-detection.pdf. Accessed 27 May 2022.

National Cancer Institute. State Cancer Profiles. Available at: https://statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov/risk/index.php?topic=colorec&risk=v14&race=00&sex=0&type=risk&sortVariableName=default&sortOrder=default#results. Accessed 27 May 2022.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of Colorectal Cancer Screening Tests: 2020 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/statistics/use-screening-tests-BRFSS.htm. Accessed 27 May 2022.

Zhan FB, Morshed N, Kluz N, et al. Spatial insights for understanding colorectal cancer screening in disproportionately affected populations, Central Texas, 2019. Prev Chronic Dis. 2021;18:E20.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030. Available at: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/cancer/increase-proportion-adults-who-get-screened-colorectal-cancer-c-07. Accessed 27 May 2022.

Dougherty MK, Brenner AT, Crockett SD, et al. Evaluation of interventions intended to increase colorectal cancer screening rates in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1645-1658.

Gupta S, Coronado GD, Argenbright K, et al. Mailed fecal immunochemical test outreach for colorectal cancer screening: Summary of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-sponsored Summit. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(4):283-298.

Health Resources & Services Administration. 2020 Health Center Data: National Data. Available at: https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/data-reporting/program-data/national/table?tableName=Full&year=2020. Accessed 27 May 2022.

Health Resources & Services Administration. Texas Health Center Program Uniform Data System (UDS) Data. Available at: https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/data-reporting/program-data/state/TX. Accessed 27 May 2022.

Taplin SH, Haggstrom D, Jacobs T, et al. Implementing colorectal cancer screening in community health centers: addressing cancer health disparities through a regional cancer collaborative. Med Care. 2008;46(9 Suppl 1):S74-S83.

Issaka RB, Avila P, Whitaker E, Bent S, Somsouk M. Population health interventions to improve colorectal cancer screening by fecal immunochemical tests: A systematic review. Prev Med. 2019;118:113-121.

Zorzi M, Battagello J, Selby K, et al. Non-compliance with colonoscopy after a positive faecal immunochemical test doubles the risk of dying from colorectal cancer. Gut. 2022;71(3):561-567.

Selby K, Baumgartner C, Levin TR, et al. Interventions to improve follow-up of positive results on fecal blood tests: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(8):565-575.

Somsouk M, Rachocki C, Mannalithara A, et al. Effectiveness and cost of organized outreach for colorectal cancer screening: a randomized, Controlled Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112(3):305-313.

Thamarasseril S, Bhuket T, Chan C, Liu B, Wong RJ. The need for an integrated patient navigation pathway to improve access to colonoscopy after positive fecal immunochemical testing: a safety-net hospital experience. J Community Health. 2017;42:551-557.

Meenan RT, Coronado GD, Petrik A, Green BB. A cost-effectiveness analysis of a colorectal cancer screening program in safety net clinics. Prev Med. 2019;120:119-125.

Pignone M, Lanier B, Kluz N, Valencia V, Chang P, Olmstead T. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mailed FIT in a safety net clinic population. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(11):3441-3447.

R Foundation. The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available at: https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 27 May 2022.

Brenner AT, Rhode J, Yang JY, et al. Comparative effectiveness of mailed reminders with and without fecal immunochemical tests for Medicaid beneficiaries at a large county health department: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2018;124(16):3346-3354.

Coronado GD, Golovaty I, Longton G, Levy L, Jimenez R. Effectiveness of a clinic-based colorectal cancer screening promotion program for underserved Hispanics. Cancer. 2011;117(8):1745-1754.

Coronado GD, Rivelli JS, Fuoco MJ, et al. Effect of reminding patients to complete fecal immunochemical testing: a comparative effectiveness study of automated and live approaches. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:72-78.

Coronado GD, Green BB, West II, et al. Direct-to-member mailed colorectal cancer screening outreach for Medicaid and Medicare enrollees: Implementation and effectiveness outcomes from the BeneFIT study. Cancer. 2020;126(3):540-548.

Goldman SN, Liss DT, Brown T, et al. Comparative effectiveness of multifaceted outreach to initiate colorectal cancer screening in community health centers: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1178-1184.

Gupta S, Halm EA, Rockey DC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of fecal immunochemical test outreach, colonoscopy outreach, and usual care for boosting colorectal cancer screening among the underserved: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173(18):1725–32.

Gupta S, Miller S, Koch M, et al. Financial incentives for promoting colorectal cancer screening: a randomized, comparative effectiveness trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(11):1630-1636.

Hendren S, Winters P, Humiston S, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of a multimodal intervention to improve cancer screening rates in a safety-net primary care practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(1):41-49.

Jager M, Demb J, Asghar A, et al. Mailed outreach is superior to usual care alone for colorectal cancer screening in the USA: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(9):2489-2496.

Jean-Jacques M, Kaleba EO, Gatta JL, Gracia G, Ryan ER, Choucair BN. Program to improve colorectal cancer screening in a low-income, racially diverse population: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(5):412-417.

Kemper KE, Glaze BL, Eastman CL, et al. Effectiveness and cost of multilayered colorectal cancer screening promotion interventions at federally qualified health centers in Washington State. Cancer. 2018;124:4121-4129.

Singal AG, Gupta S, Tiro JA, et al. Outreach invitations for FIT and colonoscopy improve colorectal cancer screening rates: A randomized controlled trial in a safety-net health system. Cancer. 2016;122(3):456-463.

Selby K, Jensen CD, Levin TR, et al. Program components and results from an organized colorectal cancer screening program using annual fecal immunochemical testing. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):145-152.

Bandi P, Minihan AK, Siegel RL, et al. Updated review of major cancer risk factors and screening test use in the United States in 2018 and 2019, with a focus on smoking cessation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(7):1287-1299.

Bharti B, May FFP, Nodora J, et al. Diagnostic colonoscopy completion after abnormal fecal immunochemical testing and quality of tests used at 8 federally qualified health centers in Southern California: opportunities for improving screening outcomes. Cancer. 2019;125:4203-4209.

Green BB, Baldwin LM, West II, Schwartz M, Coronado GD. Low rates of colonoscopy follow-up after a positive fecal immunochemical test in a medicaid health plan delivered mailed colorectal cancer screening program. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720958525.

Issaka RB, Singh MH, Oshima SM, et al. Inadequate utilization of diagnostic colonoscopy following abnormal FIT results in an integrated safety-net system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(2):375-382.

Jetelina KK, Yudkin JS, Miller S, et al. Patient-reported barriers to completing a diagnostic colonoscopy following abnormal fecal immunochemical test among uninsured patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1730-1736.

Liss DT, Brown T, Lee JY, et al. Diagnostic colonoscopy following a positive fecal occult blood test in community health center patients. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27(7):881-887.

Martin J, Halm EA, Tiro JA, et al. Reasons for lack of diagnostic colonoscopy after positive result on fecal immunochemical test in a safety-net health system. Am J Med. 2017;130(1):93.e1-93.e7.

Oluloro A, Petrik AF, Turner A, et al. Timeliness of colonoscopy after abnormal fecal test results in a safety net practice. J Community Health. 2016;41(4):864-870.

McCarthy AM, Kim JJ, Beaber EF, et al. Follow-up of abnormal breast and colorectal cancer screening by race/ethnicity. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(4):507-12.

Partin MR, Gravely AA, Burgess JF Jr, et al. Contribution of patient, physician, and environmental factors to demographic and health variation in colonoscopy follow-up for abnormal colorectal cancer screening test results. Cancer. 2017;123(18):3502-3512.

Khoong EC, Rivadeneira NA, Pacca L, et al. Extent of follow-up on abnormal cancer screening in multiple california public hospital systems: a retrospective review. J Gen Intern Med. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07657-4.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Heissel Herrera, Juanita Watkins, Felipe Hernandez, Justin Lopez, Alice Kelly, Nicholas Yagoda, and the providers and staff of the CommUnityCare network for their support.

Funding

Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) funded the program (PP170082). The content of this manuscript solely reflects the authors’ views and not those of the funding agency or the authors’ institutional affiliates.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations

Society of General Internal Medicine 2022 Annual Meeting, April 7, 2022.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Scott, R.E., Chang, P., Kluz, N. et al. Equitable Implementation of Mailed Stool Test–Based Colorectal Cancer Screening and Patient Navigation in a Safety Net Health System. J GEN INTERN MED 38, 1631–1637 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07952-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07952-0