Abstract

Peer victimization serves as a risk factor contributing to emotional and behavioral problems among college students. However, limited research has investigated the longitudinal association between peer victimization and problematic social media use (PSMU), as well as its underlying mechanism. Drawing upon the compensatory internet use theory, self-determination theory, and the stress-buffering model, we assumed that fear of missing out (FoMO) could potentially serve as a mediating factor in the relationship between peer victimization and PSMU, while school belongingness may act as a moderator for these direct and indirect associations. A total of 553 Chinese college students (Mage = 21.87, SD = 1.07) were recruited to participate in a three-wave longitudinal study (6 months apart) and completed questionnaires assessing peer victimization (T1), school belongingness (T1), FoMO (T2), and PSMU (T3). With a moderated mediation model, the results indicated the following: (1) Controlling for demographic variables, T1 peer victimization was positively and significantly associated with T3 PSMU; (2) T1 peer victimization also influenced T3 PSMU indirectly by increasing both two dimensions of T2 FoMO; (3) T1 school belongingness significantly moderated the mediating effect of T2 fear of missing social opportunities. Specifically, the indirect effect of peer victimization on PSMU via fear of missing social opportunities was found to be more pronounced when the level of school belongingness was lower. These findings are of great value in extending the studies regarding the multi-systematical risk factors causing PSMU and providing the scientific reference for the prevention and intervention of PSMU among Chinese college students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Peer victimization (e.g., verbal abuse and physical harm) has been identified as a significant public health concern that extends beyond elementary and middle schools to the college and university level (Lund & Ross, 2017; Rahman et al., 2021; Young-Jones et al., 2014). Its impact on youth can result in a range of negative consequences (Chokprajakchat & Kuanliang, 2018; Schacter, 2021). For instance, both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have demonstrated that young people who have experienced peer victimization are more likely to experience sleep problems (van Geel et al., 2016), poorer academic performance (Espelage et al., 2013), lower levels of well-being (Armitage et al., 2021), higher levels of emotional problems (e.g., anxiety and depression; Bernasco et al., 2022), and more addictive behaviors (Nepon et al., 2021). Recently, several studies have identified peer victimization as a significant risk factor for problematic Internet use among adolescents (Jia et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020; Tu et al., 2022), particularly when utilized for social purposes (Tu et al., 2022). However, these studies have been limited to cross-sectional designs and have primarily focused on elementary and secondary school students. It remains unclear whether peer victimization is associated with problematic social media use (PSMU) over time during late adolescence (i.e., college students), given the crucial role of social media in young individuals’ social lives (Kim et al., 2016). Therefore, the present study aims to investigate the longitudinal association between peer victimization and PSMU among college students, filling a crucial gap in the current literature. Additionally, it is also important to explore the underlying mechanism concerning in what way and for whom peer victimization is associated with PSMU.

To address these gaps, this study used a three-wave longitudinal design to investigate the longitudinal association between peer victimization and PSMU, while also exploring the mediating role of fear of missing out (FoMO) in this association, based on self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) and compensatory internet use theory (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014). Moreover, inspired by the stress-buffering model, school belongingness, an essential contextual factor in adolescents’ development (Valido et al., 2021), could act as a protective factor to alleviate the risk of the above direct and indirect relationships. Hence, we also explored school belongingness as a potential, yet understudied, moderator that identified those more sensitive to peer victimization and show more FoMO, thus engaging in more PSMU. The current study not only fills a gap in the literature and provides insights into potential risk factors associated with college students’ PSMU, but also contributes to the development of prevention and intervention strategies aimed at reducing the risk of peer victimization and PSMU among college students.

Literature Review

Peer Victimization and Problematic Social Media Use

PSMU refers to an addiction-like, compulsive, and uncontrollable social media use (Franchina et al., 2018). According to a recent national report (CNNIC, 2024), the number of Chinese netizens aged 20 to 29 has accounted for 13.7% of the total number of Chinese netizens. Although social media enables youths to stay connected with peers and facilitates engagement in online social activities (Jarman et al., 2021; Meshi & Ellithorpe, 2021), it can lead to a series of negative outcomes when being used in problematical ways (Al-Yafi et al., 2018; Stevens et al., 2020). Given the extensive detrimental consequences of PSMU on youth, it is necessary to explore the risk factors associated with the development of PSMU.

It is proposed that peer victimization may be a contributing risk factor for the development of PSMU. Peer victimization, recognized as a prominent stressor among young people (Rudolph et al., 2014), refers to the experience of single or repeated acts of aggression from peers, resulting in actual or perceived harm (Chokprajakchat & Kuanliang, 2018). Compensatory internet use theory (Kardefelt-winther, 2014) posits that adverse life events can trigger a motivation to use the internet to relieve negative emotions and fulfill unmet needs, which potentially leads to problematic outcomes. Accordingly, when young people suffer from peer victimization, they may struggle to form friendships and may experience negative feelings like depression, anxiety, and loneliness (Li et al., 2023), as social media could provide a convenient channel for seeking distractions (e.g., browsing feeds) and interact with other peers (e.g., chatting with friends), potentially fostering PSMU. Empirical evidence underscores the correlation between peer victimization and various forms of problematic digital behaviors, including problematic Internet use (Hsieh et al., 2019; Jia et al., 2018; Li et al., 2004). As FoMO can be conceptualized as a consequence of situational or chronic deficits in psychological needs satisfaction (Przybylski et al., 2013), it is plausible that college students who experience peer victimization may have difficulties in fulfilling these psychological needs, relatedness in particular (Menéndez Santurio et al., 2020), thereby sequentially triggers FoMO. Several papers consistently found that peer victimization was positively associated with FoMO (Dou et al., 2023; Marengo et al., 2021). Furthermore, in accordance with compensatory internet use theory (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014), using social media to compensate for negative feelings (i.e., FoMO) stemming from unmet psychological needs and cope with real-life problems (i.e., peer victimization) may result in problematic use. Therefore, in order to satisfy these psychological needs and mitigate FoMO caused by the experiences of peer victimizing, youth may tend to use social media to keep in touch with their peers (Fabris et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2021). This is because, as described before, social media facilitates young individuals to, for instance, effortlessly access their peers’ profile pages without time and location constraints, thereby resulting in PSMU. Two meta-analysis studies constantly found that FoMO was strongly related to social media use, particularly PSMU (Fioravanti et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). Therefore, we hypothesized that higher levels of peer victimization would predict higher levels of both FoM-NI and FoM-SO, which in turn will predict more PSMU (Hypothesis 2).

The Moderation Role of School Belongingness

Although peer victimization may impact college students’ PSMU through FoMO, not all college students who experience peer victimization homogeneously have increased levels of FoMO and PSMU. The stress-buffering model (Cohen & Wills, 1985) posits that positive factors can mitigate the impact of risk factors on individual development. During the undergraduate period, universities serve as a primary platform for social development among young people and play a pivotal role in sha** their behaviors (Wang et al., 2014). Specifically, school belongingness is an important school-specific environmental factor contributing to the positive development of college students (Korpershoek et al., 2020; Seon & Smith-Adcock, 2021). School belongingness refers to the emotional, cognitive, and behavioral identification and investment of students to the school they belong to (Goodenow, 1993; Pan et al., 2011). Belonging to a school community provides students with a sense of acceptance, respect, inclusion, and support (Arslan & Duru, 2017; Goodenow, 1993). Previous studies showed that students with a higher level of sense of belonging at school are more likely to have positive psychological outcomes (Korpershoek et al., 2020), for example experiencing higher levels of self-esteem (Perry & Lavins-Merillat, 2018), lower anxiety and depression (Benner et al., 2017; Raniti et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2018), and greater overall well-being (Arslan, 2018; Arslan et al., 2020; Arslan & Duru, 2017). Consequently, school belongingness has been widely acknowledged as a crucial protective factor against the development of emotional difficulties among young individuals.

In the current study, we proposed school belongingness may serve as a protective factor against the negative effects of peer victimization. As described before, peer victimization may hinder individuals’ satisfaction of their basic psychological needs, the need for relatedness, in particular, fostering FoMO. This could drive them to resort to social media as a means of compensation, potentially leading to PSMU. Nevertheless, students who have a stronger sense of school belongingness are more likely to have greater social support (i.e., engaging in more social activities at school or having better relationships with teachers). This enables them to employ effective co** strategies, seek support, and demonstrate resilience in the face of adversity, for example by enhancing self-esteem, mitigating feelings of loneliness, and promoting life satisfaction (Chen et al., 2021; Wormington et al., 2016). As a result, their basic psychological needs are less likely to remain unmet, reducing the likelihood of experiencing FoMO or engaging further in PSMU. Research by Arslan (2021) has highlighted the mediating role of school belongingness in the relationship between peer victimization and internalizing/externalizing behaviors, underscoring its potential to buffer the risks associated with bullying. Therefore, we hypothesized that school belongingness would moderate the first path of the indirect relationship between peer victimization and PSMU via FoMO (Hypothesis 3) and the direct relationship between peer victimization and PSMU (Hypothesis 4).

The Present Study

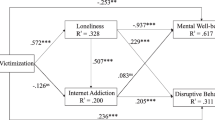

Based on the above literature review, this study proposed a moderated mediation model (see Fig. 1) to reveal the underlying mechanism in the relationship between peer victimization to PSMU among college students. We employed a three-wave longitudinal study to examine the mediating roles of FoM-NI and FoM-SO and the moderating role of school belongingness.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Using a three-wave longitudinal design with a time interval of 6 months, a total of 553 college students were recruited in February 2019 (T1) in Guangzhou, China. At Time 2 (T2), 498 students (retention rate = 90.1%) participated in this study again. Another 6 months later (Time 3, T3), 344 participants (retention rate = 66.5%) remained in the study. In this sample, participating students were between 17 and 24 years old (Mage = 21.87, SD = 1.07) at T1. In addition, 57.7% were female, 69.9% were from urban area, and students were attending education at different levels (12.5% freshmen, 19.0% sophomore students, 57.5% junior students, 11.0% senior students). Regarding parents’ level of education, 55.7% of the fathers and 53.3% of the mothers obtained a degree from middle school, 29.5% of the fathers and 19.7% of the mothers had a college degree or equivalent, and 2.5% of the fathers and 1.1% of the mothers got a graduate degree.

Given the dropouts, attrition analysis was conducted to compare age, gender, parents’ educational levels, and the levels of peer victimization and psychological sense of school membership at T1 between participants who participated in all three measurement waves (i.e., complete group) and those who dropped out at T2 and/or T3 (i.e., attrition group). The results showed that students in the complete group (Mage = 22.03, SD = 1.01) were significantly older than students in the attrition group (Mage = 21.77, SD = 1.11) at T1, t (471) = 2.87, p = 0.004, but the effect size for the difference was small, Cohen’s d = 0.24. Female students were more likely to drop out of the study than male students, χ2(1) = 4.21, p = 0.040. No other significant differences were found between the two groups. In addition, the results of the Little’s missing completely at random (MCAR) test suggested that the missing was completely at random, χ2(2) = 2.92, p = 0.232.

The study was reviewed and approved by the research ethics committee at the Guangzhou University (Protocol Number: GZHU2019018). The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were informed that they had the right to quit the study at any time without any negative consequences, even after the study had begun, and that the participation was voluntary and anonymous. The survey(s) was taken online, and participants were asked to fill in self-report questionnaires via wjx.cn. Consent forms were also collected online. After completing the questionnaires in each wave, participants were provided with a small amount of incentive as a token of appreciation for their participation. The research procedure was identical across waves.

Measures

Peer Victimization at T1

The nine-item revised Chinese version of the Peer Victimization Scale (Zhou et al., 2014), which was adapted from the Multidimensional Peer Victimization Scale (Mynard & Joseph, 2000), was used to assess students’ peer victimization (e.g., “Have you ever been isolated by your peers in the last six months”). Ratings of the items are made on a 5-point scale (1 = never to 5 = greater than or equal to 4 times). The mean score was calculated, where a higher mean score indicated a high level of perceived peer victimization. The nine items in the current sample had a Cronbach’s α value of 0.75.

School Belongingness at T1

School belongingness was measured using the Belongingness subscale of the Chinese version of the Psychological Sense of School Membership Scale (Pan et al., 2011), which was adapted from Goodenow (1993). The Belongingness subscale consists of seven items (e.g., “I took part in many activities at the school”), rated on a 5-point scale (1 = never to 5 = always). The mean score was calculated, where a higher mean score indicated a higher level of school belongingness. The seven items in the current sample had a Cronbach’s α value of 0.90.

Fear of Missing Out at T2

The eight-item revised Chinese version of the Fear of Missing Out Scale (Li et al., 2021), which was adapted from Przybylski et al. (2013), was used to assess students’ fear of missing out. This scale assessed adolescents’ FoM-NI (four items; e.g., “I get worried when I find out my friends are having fun without me”) and FoM-SO (four items; e.g., “It bothers me when I miss an opportunity to meet up with friends”). Ratings of the items are made on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all true for me to 5 = extremely true for me). Mean scores were calculated, where higher mean scores indicated higher levels of FoM-NI/FoM-SO. The Cronbach’s α values of FoM-NI and FoM-SO were 0.78 and 0.75, respectively.

Problematic Social Media Use at T3

The seven-item Chinese version of the Problematic Social Media Use Scale (Franchina et al., 2018) was used to assess students’ problematic social media use (e.g., “How frequently do you find it difficult to quit using social media”). Ratings of the items are made on a 5-point scale (0 = never to 4 = always). The mean score was calculated, where a higher mean score indicated a higher level of PSMU. The seven items in the current sample had a Cronbach’s α value of 0.88.

Covariates at T1

Student gender (1 = male, 0 = female), student age at T1, and mothers’ and fathers’ education (1 = primary school, 2 = middle school, 3 = undergraduate, 4 = graduate student) were included as covariates in all the analyses.

Statistical Analysis

First, we computed descriptive statistics and correlation analyses among all variables by IBM SPSS 26.0. Second, we conducted a mediation model by Mplus 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 2013) to examine Hypotheses 1 and 2. With the bootstrap** (N = 5000) technique (Preacher & Hayes, 2008), we tested the mediating effects of T2 FoM-NI/FoM-SO between T1 peer victimization and T3 PSMU. Third, we integrated the moderator (i.e., school belongingness) into the aforementioned mediation model to test Hypotheses 3 and 4. Across the measurement models, we handled the missing data with the full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML; Acock, 2005).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of the key variables and covariates are shown in Table 1. In specific, T1 peer victimization was positively associated with T2 FoM-NI/FoM-SO, as well as T3 problematic social media use, respectively. Both T2 FoM-NI and FoM-SO were positively associated with T3 problematic social media use. T1 school belongingness was positively associated with T2 FoM-SO.

Mediating Effects of Fear of Missing Out

The mediation model, as depicted in Fig. 2, exhibited an adequate fit to the data: χ2 (4) = 16.937, RMSEA = 0.076; CFI = 0.950, and SRMR = 0.035. After controlling for covariates, T1 peer victimization was significantly and positively associated with T2 FoM-NI (b = 0.35, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001, β = 0.21), T2 FoM-SO (b = 0.15, SE = 0.07, p = 0.031, β = 0.10), and T3 PSMU (b = 0.28, SE = 0.09, p = 0.001, β = 0.17), and both T2 FoM-NI (b = 0.24, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001, β = 0.24) and T2 FoM-SO (b = 0.21, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001, β = 0.21) were positively associated with T3 PSMU. Our results of mediation analyses (see Table 2) indicated that the mediation effects of T2 FoM-NI and T2 FoM-SO were significant, respectively. And the mediating effect of T2 FoM-NI was stronger than that of T2 FoM-SO; however, the difference was not significant.

Moderating Effects of School Belongingness

Based on the mediation model, we tested whether T1 school belongingness would moderate the direct pathway of “T1 peer victimization → T3 PSMU” and the first half of the mediated pathway of “T1 peer victimization → T2 FoM-NI/FoM-SO → T3 PSMU.” The moderated mediation model implied a good fit to the data: χ2 (13) = 34.267; RMSEA = 0.054; CFI = 0.922, and SRMR = 0.040. As shown in Table 3, the results showed that T1 school belongingness only moderated the link between T1 peer victimization and T2 FoM-SO, but did not moderate the link between T1 peer victimization and T2 FoM-NI. Moreover, T1 school belongingness did not moderate the direct relationship between T1 peer victimization and T3 PSMU either. Afterward, the follow-up simple slope test (see Fig. 3) indicated that the link between T1 peer victimization and T2 FoM-SO was stronger when T1 school belongingness was low (b = 0.17, SE = 0.05, p = 0.025) than when T1 school belongingness was high (b = − 0.004, SE = 0.06, p = 0.937).

As shown in Table 4, the moderated mediation model suggested that the indirect effect of FoM-SO was stronger when T1 school belongingness was lower than when T1 school belongingness was high. In sum, we concluded that peer victimization had a positive stronger relationship with college students’ PSMU via FoM-SO when school belongingness was lower.

Discussion

The current study examined the longitudinal association between peer victimization and PSMU among college students in China and also investigated the underlying mediating and moderating mechanisms. Findings indicated that college students who experienced more peer victimization are more likely to indulge in social media use. In addition, peer victimization also predicted PSMU via increasing FoM-NI and/or FoM-SO. Moreover, compared with college students who have higher levels of school belongingness, the indirect effect of peer victimization on PSMU through FoM-SO was stronger among those with lower levels of school belongingness. The above findings provide theoretical support for interpreting the interpersonal risky factors of PSMU and for the prevention and intervention of PSMU among college students.

The Association Between Peer Victimization and PSMU

In line with Hypothesis 1, results demonstrated that peer victimization was positively associated with PSMU over time. The results showed that college students who experienced peer victimization were more likely to engage in PSMU, indicating peer victimization is a risk factor facilitating students to use social media uncontrollably. The current study first examined the longitudinal relationship between peer victimization and PSMU, and the finding is in line with the previous cross-sectional studies suggesting peer victimization is positively associated with PSMU (Feng et al., 2023), problematic internet use (Zhai et al., 2019), and problematic smartphone use (Liu et al., 2020). Furthermore, the finding provides further support for the compensatory internet use theory and expands its applicability to the context of social media use.

The Mediation of Fear of Missing Out

This study is among the first to investigate the mediating role of two dimensions of FoMO between peer victimization and PSMU in explaining why victimized students engage in PSMU. In line with Hypothesis 2, our finding suggested that college students who experienced higher levels of peer victimization exhibit a stronger inclination towards obtaining up-to-date information about their peers (i.e., FoM-NI) and engaging in social interactions with them (i.e., FoM-SO), ultimately leading to PSMU. The finding is consistent with previous studies (Boustead & Flack, 2021; Dou et al., 2023; Marengo et al., 2021) and provides support for self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) and compensatory internet use theory (Daniel Kardefelt-Winther, 2014), suggesting that suffering from peer victimization may impede people’s basic psychological needs, leading to FoMO on social connections and status message with friends. Meanwhile, using social media as a co** strategy to fulfill the unmet psychological needs and mitigate negative emotions caused by real-life difficulties, PSMU may ensue.

The Moderated Role of School Belongingness

Another contribution of this study is examining the moderating role of school belongingness. Our expectation that school belongingness moderates the first path of the relationship between peer victimization and PSMU via FoMO (Hypothesis 3) was partially confirmed. Moreover, our expectation that school belongingness moderates the direct relationship between peer victimization and PSMU (Hypothesis 4) was not confirmed. Results showed that school belongingness only moderated the relationship between peer victimization and FoM-SO and the mediating effect of FoM-SO, suggesting that for those students who have higher levels of school belongingness, when they encountered peer victimization, they did not develop higher levels of FoM-SO; ultimately, they did not result in PSMU. In other words, school belongingness acted as a protective factor buffering the risk of peer victimization on FoM-SO, and further PSMU, supporting the stress-buffering model (Cohen & Wills, 1985). The finding is in line with the previous studies suggesting school belongingness is a protective factor preventing young people from engaging in negative emotions and problematic behaviors (Arslan, 2021; Seon & Smith-Adcock, 2021; Valido et al., 2021). Schools play a vital role in fostering student groups and social networks, offering students unique opportunities to develop a sense of belonging. Studies showed that school belonging relates to the number of group memberships and extracurricular activities (Allen et al., 2018). It is comprehensible that those students who have higher levels of school belongingness are more likely to have other social groups beyond the group where they experience peer victimization. Consequently, when they experience peer victimization, they are less likely to develop a fear of missing social opportunities, ultimately resulting in PSMU. Our findings highlight the protective role of school belongingness against the negative impacts of peer victimization on adolescents’ mental health and problematic behavior.

Implications

This study reveals the potential mechanism that connects peer victimization and increased PSMU among college students, which has important implications for the prevention and intervention strategies to reduce students’ problematic social media use. First, our findings indicate that peer victimization is an important risk driver for predicting PSMU in college students. This suggests that intervening in peer victimization may be an effective means of mitigating PSMU in college students, for example, at the beginning of the freshman year, training on interpersonal relationships, communication skills, respect for others, etc. to help students develop a healthy social awareness. In addition, the school has set up a mental health center to provide relationship counseling and support for students who have been victimized to help them reduce their mental stress and establish anonymous reporting channels, with which students can safely report abuse and avoid retaliation (Espelage, 2014). Second, FoMO is found to be a mediator in the “peer victimization–PSMU” link. This suggests that alleviating college students’ fear of missing out may be another effective way to prevent college students from becoming addicted to social media. Therefore, schools and parents can encourage students to make regular digital disconnections to clean up unwanted social media attention and unwanted messages, which helps reduce information overload. At the same time, psychology teachers should assist students in cultivating their focus and learning to concentrate on their current tasks or activities. This can be achieved through practices such as meditation, deep breathing exercises, or focused training. Finally, the stress-buffering effect of school belongingness implies that effective psychological interventions aiming at strengthening school belongingness are especially necessary for victimized students (Li & Zhu, 2022). For instance, schools can strive to create a positive, friendly, and inclusive learning environment to promote positive changes in student attitudes and behaviors. This can help college students mitigate their FoM-SO.

Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations should be taken into account when interpreting the results in this study. First, because of the self-report measures, methodological bias (e.g., social desirability) was inevitable. Therefore, readers should interpret the findings with caution, and it would be ideal for future research to use multi-informant measures to assess the key variables. Second, our sample is college students in southern China, which may not be representative of Chinese students. Future research needs to examine whether the findings of the present research can be generalized to a more representative sample of Chinese college students and to college students from other cultural backgrounds. Third, we only explore the traditional type of peer victimization (i.e., offline peer victimization). However, cyberbullying is also a vital part of peer victimization among undergraduates, which causes a significant negative impact. Future research should extend our findings into cyberbullying.

Conclusion

PSMU is a concerning issue among Chinese college students. Understanding the mechanism and the developmental process is important for the prevention and intervention of reducing PSMU among Chinese college students. This present study examined the potential mechanism regarding in what way and for whom peer victimization was associated with PSMU. Overall, our study indicated that peer victimization is a risk factor contributing to increased PSMU and it influences PSMU via FoMO. Additionally, higher levels of school belongingness prevented the negative effect of peer victimization on FoMO, resulting in more PSMU.

Change history

02 July 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01352-7

References

Acock, A. C. (2005). Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(4), 1012–1028. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00191.x

Al-Yafi, K., El-Masri, M., & Tsai, R. (2018). The effects of using social network sites on academic performance: The case of Qatar. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 31(3), 446–462. https://doi.org/10.1108/jeim-08-2017-0118

Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8

Armitage, J. M., Wang, R. A. H., Davis, O. S. P., Bowes, L., & Haworth, C. M. A. (2021). Peer victimization during adolescence and its impact on wellbeing in adulthood: A prospective cohort study. Bmc Public Health, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10198-w

Arslan, G. (2018). Understanding the association between school belonging and emotional health in adolescents. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 7(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.17583/ijep.2018.3117

Arslan, G. (2021). School bullying and youth internalizing and externalizing behaviors: Do school belonging and school achievement matter? International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20, 2460–2477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00526-x

Arslan, G., & Duru, E. (2017). Initial development and validation of the school belongingness scale. Child Indicators Research, 10(4), 1059–1059. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-016-9418-7

Arslan, G., Allen, K. A., & Ryan, T. (2020). Exploring the impacts of school belonging on youth wellbeing and mental health among Turkish adolescents. Child Indicators Research, 13(5), 1619–1635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09721-z

Benner, A. D., Boyle, A. E., & Bakhtiari, F. (2017). Understanding students’ transition to high school: Demographic variation and the role of supportive relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(10), 2129–2142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0716-2

Bernasco, E. L., van der Graaff, J., Meeus, W. H. J., & Branje, S. (2022). Peer victimization, internalizing problems, and the buffering role of friendship quality: Disaggregating between- and within-person associations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(8), 1653–1666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01619-z

Boustead, R., & Flack, M. (2021). Moderated-mediation analysis of problematic social networking use: The role of anxious attachment orientation, fear of missing out and satisfaction with life. Addictive Behaviors, 119, 106938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106938

Chen, I. H., Gamble, J. H., & Lin, C. Y. (2021). Peer victimization’s impact on adolescent school belonging, truancy, and life satisfaction: A cross-cohort international comparison. Current Psychology, 42, 1402–1419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01536-7

Chokprajakchat, S., & Kuanliang, A. (2018). Peer victimization: A review of literature. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1403396

CNNIC. (2024). The 53rd statistical report on China’s internet development. https://www.cnnic.cn/NMediaFile/2024/0325/MAIN1711355296414FIQ9XKZV63.pdf

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.98.2.310

Collins, W. A., & Laursen, B. (2004). Changing relationships, changing youth: Interpersonal contexts of adolescent development. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 24(1), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431603260882

Dempsey, A. E., O’Brien, K. D., Tiamiyu, M. F., & Elhai, J. D. (2019). Fear of missing out (FoMO) and rumination mediate relations between social anxiety and problematic Facebook use. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 9, 100150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2018.100150

Dou, K., Li, Y. Y., Wang, L. X., & Nie, Y. G. (2023). Fear of missing out or social avoidance? The relationship between peer exclusion and problematic social media use among adolescents in Guangzhou and Macao. Journal of Psychological Science, 46(5), 1081–1089.

Espelage, D. L. (2014). Ecological theory: Preventing youth bullying, aggression, and victimization. Theory into Practice, 53(4), 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2014.947216

Espelage, D. L., Hong, J. S., Rao, M. A., & Low, S. (2013). Associations between peer victimization and academic performance. Theory into Practice, 52(4), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2013.829724

Fabris, M. A., Marengo, D., Longobardi, C., & Settanni, M. (2020). Investigating the links between fear of missing out, social media addiction, and emotional symptoms in adolescence: The role of stress associated with neglect and negative reactions on social media. Addictive Behaviors, 106, 106364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106364

Feng, J., Chen, J., Jia, L., & Liu, G. (2023). Peer victimization and adolescent problematic social media use: The mediating role of psychological insecurity and the moderating role of family support. Addictive Behaviors, 144, 107721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107721

Fioravanti, G., Casale, S., Benucci, S. B., Prostamo, A., Falone, A., Ricca, V., & Rotella, F. (2021). Fear of missing out and social networking sites use and abuse: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 122, 106839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106839

Franchina, V., Vanden Abeele, M., Van Rooij, A. J., Lo Coco, G., & De Marez, L. (2018). Fear of missing out as a predictor of problematic social media use and phubbing behavior among flemish adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(10)2319.https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102319

Fu, W., Li, R., & Liang, Y. (2023). The relationship between stress perception and problematic social network use among Chinese college students: The mediating role of the fear of missing out. Behavioral Sciences, 13(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13060497. Article 6.

Goodenow, C. (1993). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools, 30(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(199301)30:13.0.CO;2-X

Hsieh, Y. P., Wei, H. S., Hwa, H. L., Shen, A. C. T., Feng, J. Y., & Huang, C. Y. (2019). The effects of peer victimization on children’ s internet addiction and psychological distress: The moderating roles of emotional and social intelligence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 2487–2498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1120-6

Hu, Z., Zhu, Y., Li, J., Liu, J., & Fu, M. (2023). The COVID-19 related stress and social network addiction among Chinese college students: A moderated mediation model. PLOS ONE, 18(8), e0290577. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0290577

Jarman, H. K., Marques, M. D., McLean, S. A., Slater, A., & Paxton, S. J. (2021). Motivations for social media use: Associations with social media engagement and body satisfaction and well-being among adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(12), 2279–2293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01390-z

Jia, J., Li, D., Li, X., Zhou, Y., Wang, Y., Sun, W., & Zhao, L. (2018). Peer victimization and adolescent internet addiction: The mediating role of psychological security and the moderating role of teacher-student relationships. Computers in Human Behavior, 85, 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.042

Kardefelt-winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059

Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). The moderating role of psychosocial well-being on the relationship between escapism and excessive online gaming. Computers in Human Behavior, 38, 68–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.05.020

Kim, Y., Wang, Y., & Oh, J. (2016). Digital media use and social engagement: How social media and smartphone use influence social activities of college students. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking, 19(4), 264–269. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0408

Korpershoek, H., Canrinus, E. T., Fokkens-Bruinsma, M., & de Boer, H. (2020). The relationships between school belonging and students’ motivational, social-emotional, behavioural, and academic outcomes in secondary education: A meta-analytic review. Research Papers in Education, 35(6), 641–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2019.1615116

Li, L., & Zhu, J. (2022). Peer victimization and problematic internet game use among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model of school engagement and grit. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues, 41(4), 1943–1950. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00718-z

Li, X., Luo, X., Zheng, R., **, X., Mei, L., **e, X., Gu, H., Hou, F., Liu, L., Luo, X., Meng, H., Zhang, J., & Song, R. (2019). The role of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and school functioning in the association between peer victimization and internet addiction: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Affective Disorders, 256, 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.05.080

Li, Y. Y., Huang, Y. T., & Dou, K. (2021). Validation and psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the fear of missing out scale. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 9896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189896

Liu, Q. Q., Yang, X. J., Hu, Y. T., & Zhang, C. Y. (2020). Peer victimization, self-compassion, gender and adolescent mobile phone addiction: Unique and interactive effects. Children and Youth Services Review, 118, 105397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105397

Lund, E. M., & Ross, S. W. (2017). Bullying perpetration, victimization, and demographic differences in college students: A review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse, 18(3), 348–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015620818

Marengo, D., Settanni, M., Fabris, M. A., & Longobardi, C. (2021). Alone, together: Fear of missing out mediates the link between peer exclusion in WhatsApp classmate groups and psychological adjustment in early-adolescent teens. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(4), 1371–1379. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407521991917

Matthews, T., Caspi, A., Danese, A., Fisher, H. L., Moffitt, T. E., & Arseneault, L. (2022). A longitudinal twin study of victimisation and loneliness from childhood to young adulthood. Development and Psychopathology, 34(1), 367–377. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579420001005

Menéndez Santurio, J. I., Fernández-Río, J., Estrada, C., J. A., & González-Víllora, S. (2020). Connections between bullying victimization and satisfaction/frustration of adolescents’ basic psychological needs. Revista De Psicodidáctica (English ed), 25(2), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psicoe.2019.11.002

Meshi, D., & Ellithorpe, M. E. (2021). Problematic social media use and social support received in real-life versus on social media: Associations with depression, anxiety and social isolation. Addictive Behaviors, 119, 106949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106949

Muthén, B., & Muthén, L. (2013). Mplus 7.1. Muthén & Muthén.

Mynard, H., & Joseph, S. (2000). Development of the multidimensional peer-victimization scale. Aggressive Behavior, 26(2), 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(2000)26:2<169::AID-AB3>3.0.CO;2-A

Nepon, T., Pepler, D. J., Craig, W. M., Connolly, J., & Flett, G. L. (2021). A longitudinal analysis of peer victimization, self-esteem, and rejection sensitivity in mental health and substance use among adolescents. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19(4), 1135–1148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00215-w

Pan, F. D., Wang, Q., & Song, L. L. (2011). A research on reliability and validity of psychological sense of school membership scale. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 19(2), 200–202. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2011.02.011

Perry, J. C., & Lavins-Merillat, B. D. (2018). Self-esteem and school belongingness: A cross-lagged panel study among urban youth. Professional School Counseling, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X19826575. Article 2156759X19826575

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Przybylski, A. K., Kou, M., Dehaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841–1848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014

Rahman, M., Hasan, M., Hossain, A., & Kabir, Z. (2021). Consequences of bullying on university students in Bangladesh. Management, 25(1), 186–208. https://doi.org/10.2478/manment-2019-0066

Ramazanoğlu, M. (2020). The relationship between high school students’ internet addiction, social media disorder, and smartphone addiction. World Journal of Education, 10(4), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v10n4p139

Raniti, M., Rakesh, D., Patton, G. C., & Sawyer, S. M. (2022). The role of school connectedness in the prevention of youth depression and anxiety: A systematic review with youth consultation. Bmc Public Health, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14364-6

Rudolph, K. D., Lansford, J. E., Agoston, A. M., Sugimura, N., Schwartz, D., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (2014). Peer victimization and social alienation: Predicting deviant peer affiliation in middle school. Child Development, 85(1), 124–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12112

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.55.1.68

Schacter, H. L. (2021). Effects of peer victimization on child and adolescent physical health. Pediatrics, 147(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-003434. Article e2020003434

Seon, Y., & Smith-Adcock, S. (2021). School belonging, self-efficacy, and meaning in life as mediators of bulling victimization and subjective well-being in adolescents. Psychology in the Schools, 58(9), 1753–1767. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22534

Sever, M., & Ozdemir, S. (2022). Stress and entertainment motivation are related to problematic smartphone use: Fear of missing out as a mediator. ADDICTA: The Turkish Journal on Addictions, 9(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.5152/addicta.2021.21067

Skog, O. J. (2003). Chapter 6 - Addiction: Definitions and Mechanisms. In R. E. Vuchinich & N. Heather (Eds.), Choice, Behavioural Economics and Addiction (pp. 157–182). Pergamon. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008044056-9/50047-6

Stevens, C., Zhang, E., Cherkerzian, S., Chen, J. A., & Liu, C. H. (2020). Problematic internet use/computer gaming among US college students: Prevalence and correlates with mental health symptoms. Depression and Anxiety, 37(11), 1127–1136. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23094

Tu, W., Jiang, H., & Liu, Q. (2022). Peer victimization and adolescent mobile social addiction: Mediation of social anxiety and gender differences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10978. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710978

Valido, A., Ingram, K., Espelage, D. L., Torgal, C., Merrin, G. J., & Davis, J. P. (2021). Intra-familial violence and peer aggression among early adolescents: Moderating role of school sense of belonging. Journal of Family Violence, 36(1), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-020-00142-8

van Geel, M., Goemans, A., & Vedder, P. H. (2016). The relation between peer victimization and slee** problems: A meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 27, 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2015.05.004

Wang, W., Vaillancourt, T., Brittain, H. L., McDougall, P., Krygsman, A., Smith, D., Cunningham, C. E., Haltigan, J. D., & Hymel, S. (2014). School climate, peer victimization, and academic achievement: Results from a multi-informant study. School Psychology Quarterly, 29(3), 360–377. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000084

Wang, Y., Liu, B., Zhang, L., & Zhang, P. (2022). Anxiety, Depression, and Stress Are Associated With Internet Gaming Disorder During COVID-19: Fear of Missing Out as a Mediator. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.827519

Wormington, S. V., Anderson, K. G., Schneider, A., Tomlinson, K. L., & Brown, S. A. (2016). Peer victimization and adolescent adjustment: Does school belonging matter? Journal of School Violence, 15(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2014.922472

Yang, H., Liu, B., & Fang, J. (2021). Stress and problematic smartphone use severity: Smartphone use frequency and fear of missing out as mediators. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 659288. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.659288

Young-Jones, A., Fursa, S., Byrket, J. S., & Sly, J. S. (2014). Bullying affects more than feelings: The long-term implications of victimization on academic motivation in higher education. Social Psychology of Education, 18(1), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-014-9287-1

Zhai, B., Li, D., Jia, J., Liu, Y., Sun, W., & Wang, Y. (2019). Peer victimization and problematic internet use in adolescents: The mediating role of deviant peer affiliation and the moderating role of family functioning. Addictive Behavior, 96, 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.04.016

Zhang, M. X., Mou, N. L., Tong, K. K., & Wu, A. M. S. (2018). Investigation of the effects of purpose in life, grit, gratitude, and school belonging on mental distress among Chinese emerging adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102147. Article 2147

Zhang, Y., Li, S., & Yu, G. (2021). The relationship between social media use and fear of missing out: A meta-analysis. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 53(3), 273–290.

Zhao, J., Ye, B., Yu, L., & **a, F. (2022). Effects of stressors of COVID-19 on Chinese college students’ problematic social media use: A mediated moderation model. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 917465. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.917465

Zhou, S. S., Yu, C. F., Xu, Q., Wei, C., & Lin, Z. (2014). Peer victimization and problematic online game use among junior middle school students: Mediation and moderation effects. Educational Measurement and Evaluation, 7(10), 44–48. https://doi.org/10.16518/j.cnki.emae.2014.10.004

Funding

Plan of Philosophy and Social Science of Guangdong Province (GD22CXL05).Guangzhou Education Scientific Research Project (202113700).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: The graphic for Fig. 2 has been replaced to eliminate type that was in red.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dou, K., Wang, ML., Li, YY. et al. The Longitudinal Association Between Peer Victimization and Problematic Social Media Use Among Chinese College Students: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01304-1

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01304-1