Abstract

Purpose

Although various studies have improved our knowledge about the clinical features and outcomes of acute kidney injury develo** in the hospital (AKI-DI) in elderly subjects, data about acute kidney injury develo** outside the hospital (AKI-DO) in elderly patients (age ≥ 65 years) are still extremely limited. This study was performed to investigate prevalence, clinical outcomes, hospital cost and related factors of AKI-DO in elderly and very elderly patients.

Methods

We conducted a prospective, observational study in patients (aged ≥ 65 years) who were admitted to our center between May 01, 2012, and May 01, 2013. Subjects with AKI-DO were divided into two groups as “elderly” (group 1, 65–75 years old) and “very elderly” (group 2, >75 years old). Control group (group 3) consisted of the hospitalized patients aged 65 years and older with normal serum creatinine level. In-hospital outcomes and 6-month outcomes were recorded. Rehospitalization rate within 6 months of discharge was noted. Hospital costs and mortality rates of each group were investigated. Risk factors for AKI-DO were determined.

Results

The incidence of AKI-DO that required hospitalization in elderly and very elderly patients was 5.8 % (136/2324) and 11 % (100/905), respectively (p < 0.001), with an overall incidence of 7.3 % (236/3229). Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was developed in 43.4 % of group 1 and 67 % of group 2 within the 6 months of discharge (p < 0.001). Progression to CKD was significantly lower in the control group than in groups 1 and 2 (p < 0.001). Mortality rates for groups 1, 2 and 3 were 23.5 % (n = 32), 31 % (n = 31) and 4.2 % (n = 8), respectively (p < 0.05). Rehospitalization rate within the 6 months of discharge for the groups with AKI-DO was higher than for the control group (p < 0.001). Hospital cost of groups 1 and 2 was significantly higher than that of the control group (p < 0.001). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (OR: 6.839, 95 % CI = 4.392–10.648), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) (OR: 7.846, 95 % CI = 5.161–11.928), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) (OR: 6.466, 95 % CI = 4.813–8.917), radiocontrast agents (OR: 8.850, 95 % CI = 5.857–13.372), hypertension (OR: 4.244, 95 % CI = 2.729–6.600), diabetes mellitus (OR: 2.303, 95 % CI = 1.411–3.761), heart failure (OR: 3.647, 95 % CI = 2.276–5.844) and presence of infection (OR: 3.149, 95 % CI = 1.696–5.845) were found as the risk factors for AKI-DO in elderly patients (p < 0.001 for all). Patients with AKI-DO had higher 6-month mortality rate (HR 1.721, 95 % CI: 1.451–2.043, p < 0.001). Mortality risk increased 0.519 times at 20th day.

Conclusions

The incidence of AKI-DO requiring hospitalization is higher in very elderly patients than elderly ones, especially in male gender. Use of ACEI, ARB, NSAID and radiocontrast agents is the main risk factors for the development of AKI-DO in the elderly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Twelve percent of the total population consist of elderly individuals, and it is expected to rise to 21 % by the year 2040. This tendency causes a gradual rise in the number of rehabilitation beds, emergency and acute care beds, as seen mainly in the developed nations [1]. In this sense, the specific renal problems along with their management should be well defined in elderly people.

The increased incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) in the elderly people is favored by certain predisposing factors such as histological and functional alterations in the aged kidneys, different pharmacokinetics of drugs, polypharmacy and associated comorbid diseases like diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HT) and heart failure [2].

Acute kidney injury, even mild or moderate, can result in increased morbidity and mortality [3]. Elderly adults are more susceptible to AKI, but it is more important to understand whether AKI is associated with more or less severe consequences in elderly population. Although various studies have expanded our knowledge about clinical features and outcomes of acute kidney injury develo** in the hospital (AKI-DI) in the elderly subjects [4], data about acute kidney injury develo** outside the hospital (AKI-DO) in the elderly (age ≥ 65 years old) and very elderly patients (age ≥ 75 years old) are extremely limited. Although the incidence of AKI-DO was 3.5 times more than AKI-DI [5] and increased mortality was reported [6], the studies carried out are still not enough.

The aim of this study is to investigate the incidence, clinical presentations, risk factors, associated factors, mortality, hospital cost and outcomes of AKI-DO in elderly and very elderly patients.

Patients and methods

A prospective, observational case–control study was designed, and patients aged 65 years and older who admitted to our center between May 01, 2012, and May 01, 2013, were included in the study. Data collection and analysis of the study were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (2012/104, 22.04.2012). Written informed consent was obtained from patients for their participation in the study.

Subjects of the study

Patients were eligible for enrollment if they were aged ≥ 65 years and were diagnosed AKI-DO that needed hospitalization. As average life expectancy is 74 years in our country (http://www.tuik.gov.tr/PreHaberBultenleri.do?id=8428), patients were divided into two groups as “elderly” (group 1, 65–75 years) and “very elderly” (group 2, >75 years). Patients aged 65 years old and older who were hospitalized with normal serum creatinine level were included in the control group (group 3). The criteria for diagnosis of AKI were increase in serum creatinine level by 0.3 mg/dl within 48 h or increase in serum creatinine level to 1.5 times baseline, which is known or presumed to have occurred within the prior 7 days or urine volume less than 0.5 ml/kg/h for 6 h [7]. Patients were followed up for 6 months after discharge from the hospital. Return of serum creatinine level back to normal range (serum creatinine: 0.6–1.1 mg/dl) was accepted as complete recovery.

Data collection

Vital signs, plasma glucose, urea, serum creatinine, sodium, potassium, magnesium, chloride, calcium, phosphate, serum albumin, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), liver enzymes, C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, analysis of arterial blood gases, urinalysis and albumin/creatinine ratio in spot urine sample were measured at admission for all subjects.

Serum urea, creatinine, sodium, fasting blood glucose, albumin were assessed by “Olympus AU 640, Japan.” Serum potassium, magnesium, chloride, calcium, phosphorus were measured by “Roche Cobas İntegra 800 Chemistry Analyzer, Switzerland.”

Urinalysis was evaluated by “Urisys 2400/UF100, Japan.” Albumin/creatinine ratio in spot urine was assessed by “Roche Cobas İntegra 800 Chemistry Analyzer, Switzerland.”

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated for each participant by “Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration” (CKD-EPI) formula which can be shown as CKD-EPI = eGFR = 141 × min(Scr/κ,1)α × max(Scr/κ,1)−1.209 × 0.993Age × 1.018 [if female] × 1.159 [if black] [8].

Exclusion criterias

Patients younger than 65 years of age, patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) (eGFR < 60 ml/min, persistent proteinuria [>1 g/day], persistent glomerular hematuria or persistently high serum creatinine level), patients with renal anatomic abnormalities including polycystic kidney disease, atrophic kidney(s) (vertical length <9 cm), bilateral renal artery stenosis, renal artery stenosis of solitary kidney, transplanted kidney and patients with AKI-DI were all excluded from the study.

Etiologic factors

Use of nephrotoxic agents like intravenous contrast agents, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB), aminoglycoside, spironolactone, loop diuretics was recorded. Factors which may cause prerenal AKI like diarrhea, vomiting, decrease in oral intake, gastrointestinal bleeding were noted. Respiratory, urinary and gastrointestinal system infections were recorded. Comorbid diseases like DM, HT, cirrhosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Alzheimer’s disease, neoplastic diseases, congestive heart failure, stroke, and eventually total number of comorbidities were recorded. The reasons for admission to the hospital were analyzed. Postrenal causes such as benign prostatic hypertrophy and prostatic adenocarcinoma, pelvic malignancies which may result in urethral obstruction, retroperitoneal fibrosis were investigated. Renal biopsy was performed for the patients whose etiology of prolonged AKI could not be determined.

Clinical outcomes of AKI-DO

Clinical outcomes of AKI-DO like complete recovery, progression to CKD and in-hospital mortality and 6-month mortality rates were recorded. Clinical outcomes and mortality reasons of each group were compared with each other. Need for hemodialysis (HD), intensive care unit (ICU) and mechanic ventilator (MV), and length of hospital stay, hospital cost, mortality rates of groups were compared with each other. Rehospitalization rate of each group was calculated.

Related factors of AKI-DO

Associations of AKI-DO and age, sex, serum potassium level, presence of infection, need for HD, need for ICU, duration of hospitalization, clinical outcomes (mortality, progression to CKD, recovery), hospital cost, number of comorbidities, use of NSAID, ACEI, ARB, radiocontrast agents were investigated.

Risk factors for AKI-DO

Age, sex, number of comorbidities, presence of infection, HT, DM, heart failure, use of NSAID, ACEI, ARB and radiocontrast agents were investigated whether they were risk factors for AKI-DO. In addition to this, risk of AKI-DO due to specific drug combinations was investigated. Risk of AKI-DO in the presence of specific comorbid disease was investigated. Mortality risk analysis was performed for patients with AKI-DO by using serum creatinine values.

Invoices regarding laboratory tests, imaging procedures, surgical interventions, histopathologic investigations, medications, feeding, consultations, medical equipment, and all supportive care performed during the hospital stay were evaluated in order to determine total hospital cost.

Statistical analysis

MedCalc packet program was used for statistical analysis. Shapiro–Wilk test was used to identify whether variables were normal distribution. Mean ± standard deviation was used for descriptive statistics for non-normal distribution variables. The mean comparisons of binary groups were done with Student’s t test. Spearman correlation was used to test correlation between two continuous variables. Chi-square statistics were used to compare two categorical variables. Logistic regression and odds ratios were used for risk analysis.

Results

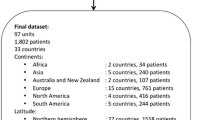

The study included 3229 patients, aged ≥ 65 years. Group 1 consisted of 136 participants [male/female (M/F): 78/58], whereas group 2 consisted of 100 participants (M/F: 58/42), and group 3 (control group) included 190 subjects (M/F: 112/78).

Incidence of AKI-DO

The incidence of AKI-DO in group 1 and group 2 was 5.8 % (136/2324) and 11 % (100/905), respectively (p < 0.001), whereas the overall incidence of AKI-DO was 7.3 % (236/3229) in elderly patients. Incidence of AKI-DO was 4.2 % for males and 3 % for females (p < 0.05). Clinical and laboratory parameters of the groups are shown in Table 1.

Etiology of AKI-DO

Clinical features of the groups at admission are listed in Table 2. Frequency of prerenal, renal and postrenal causes for AKI-DO was 63, 27 and 10 % in group 1 and 63, 29 and 8 % in group 2, respectively. Prerenal factors were the most common cause of AKI-DO in both groups (p < 0.05). Inadequate oral intake was the most common prerenal factor in both groups. Use of NSAID, ACEI, ARB, radiocontrast agents, loop diuretics, spironolactone and other nephrotoxic agents was 14.7 and 14, 37.5 and 35, 11.8 and 10, 11.8 and 15, 2 and 3, 4.4 and 3, 5.2 and 5.4 % for groups 1 and 2, respectively. Administration of nephrotoxic drugs was similar for two groups (p > 0.05).

The most common reasons for admission to the hospital were as follows: infection/fever 40 versus 43 %, dyspnea 22 versus 11 %, oliguria 12 versus 17 %, vomiting/diarrhea 12 versus 13 %, others 14 versus 16 %, for group 1 and 2, respectively. Fever/focal infection was the most common reason for admission in both groups. No significant difference was obtained between the admission reasons of two groups (p > 0.05), other than dyspnea (p < 0.05).

Males were exposed to radiocontrast agents more common than women (18.6 vs. 9.2 %, p < 0.05), and use of NSAID (17.3 vs. 11.4 %, p < 0.05), ACEI (41 vs. 29 %, p < 0.05), ARB (13.1 vs. 8 %, p < 0.05) was also more common in males. Other etiologic factors were similar in both groups.

Comorbidities

In this study, majority of the patients with AKI-DO had ≥2 comorbid diseases. Among AKI-DO patients, 81.3 % had ≥2 comorbid diseases, whereas 18.7 % had <2 comorbid diseases (p < 0.001). When groups were analyzed separately 73.5 versus 92 % of subjects had ≥2 comorbid diseases and 26.5 versus 8 % had <2 comorbid diseases for groups 1 and 2, respectively (p < 0.05 for all). Only 25.8 % of control group had ≥2 comorbid diseases, whereas 74.2 % had <2 comorbid diseases (p < 0.05). In control group, the number of the subjects with ≥2 comorbid diseases was significantly lower in comparison with groups 1 and 2 (p < 0.001). A total of 85.2 % of males and 72 % of females had ≥2 comorbid diseases (p < 0.05).

Clinical outcomes of AKI-DO

The length of hospital stay, need for MV support, number of comorbidities were found to be higher in very elderly patients than in elderly subjects (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Need for ICU was 33.8 % for all patients with AKI-DO. Need for ICU in control group was significantly lower than in groups 1 and 2 (p < 0.05) (Table 2). Need for HD was 32.6 % for all patients with AKI-DO, whereas it was significantly lower in control group than in groups 1 and 2 (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Rehospitalization rate of AKI-DO within 6 months after discharge was 15.6 % for all patients with AKI-DO. Rehospitalization was needed for 15 % of group 1 patients and 17 % of group 2 patients (p > 0.05), whereas 8.4 % of patients in control group needed rehospitalization within this period. Need for rehospitalization during 6 months after discharge in groups 1 and 2 were higher than in control group (p < 0.001).

Chronic kidney disease was developed in 53.3 % of the patients with AKI-DO during 6 months after discharge. Chronic kidney disease was developed 43.4 % of group 1 and 67 % of group 2 (p < 0.001), whereas CKD developed in 5.3 % of control group. Development of CKD was lower in control group than in groups 1 and 2 (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Mortality rates of the patients with AKI-DO for the 6 months following their discharge were 26.6 %. Mortality rate of group 1 was 23.5 %, whereas it was 31 % for group 2 (p < 0.05) and 4.2 % for control group. Mortality rate of control group was significantly lower than that of groups 1 and 2 (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Complete recovery was achieved in 20.1 % of AKI-DO patients within 6 months following discharge. When groups were analyzed, complete recovery rate of group 1 was 33.1 %, whereas it was 2 % for group 2 (p < 0.001) and 90.5 % for control group (Table 2).

Hospital expenditure was 1715 ± 871 USD (United States dollar) for all patients in groups 1 and 2. The mean hospital costs for elderly and very elderly groups were found to be 1383.3 ± 529.6 USD and 2167 ± 1213 USD, respectively (p < 0.05). Hospital cost for control group was 120.7 ± 90.3 USD. Hospital cost for control group was significantly lower than for groups 1 and 2 (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Causes of mortality

The main causes of death were sepsis (61 vs. 63 %), cardiovascular problems (23 vs. 22 %), and miscellaneous (16 vs. 15 %) in elderly and very elderly subjects, respectively (p > 0.05).

Related factor of AKI-DO

There was no association between serum creatinine and age (r = 0.043; p = 0.379). There was positive correlation between serum creatinine and serum potassium level, duration of hospital stay, number of comorbid diseases, presence of infection, need for hemodialysis, need for ICU, mortality, NSAID, ACEI, ARB, spironolactone, loop diuretics and contrast agents (r = 0.368, r = 0.281, r = 0.688, r = 0.783, r = 0.807, r = 0.731, r = 0.406, r = 0.578, r = 0.675, r = 0.876, r = 0.767, r = 0.403, r = 0.566, respectively, p < 0.001 for all).

Risk factors for AKI-DO

Risk factors for AKI-DO for elderly patients were as follows: NSAID (OR: 6.839, 95 % CI = 4.392–10.648), ACEI (OR: 7.846, 95 % CI = 5.161–11.928), ARB (OR: 6.466, 95 % CI = 4.813–8.917), contrast agents (OR: 8.850, 95 % CI = 5.857–13.372), HT (OR: 4.244, 95 % CI = 2.729–6.600), DM (OR: 2.303, 95 % CI = 1.411–3.761), heart failure (OR: 3.647, 95 % CI = 2.276–5.844), presence of infection (OR: 3.149, 95 % CI = 1.696–5.845) (p < 0.001 for all).

Age and sex were not independent risk factors for AKI-DO (p > 0.05). Risk factors for AKI-DO are shown in Table 3. Risk of AKI-DO due to specific substance combinations is shown in Table 4. Use of ACEI, ARB, NSAID, loop diuretics, spironolactone, radiocontrast agents increases risk of AKI-DO more in the presence of comorbid diseases like heart failure, HT, DM. Risk of AKI-DO in a diabetic patient for the use of ACEI, ARB, spironolactone, NSAID, radiocontrast agents or loop diuretics was as follows: OR: 20.25 (95 % CI = 8.89–82.11), OR: 26.83 (95 % CI = 4.92–146.15), OR: 21.54 (95 % CI = 2.46–5.84), OR: 14.50 (95 % CI = 5.16–30.35), OR: 12.50 (95 % CI = 4.88–31.99), OR: 3.34 (95 % CI = 5.63–9.93), respectively. Risk of AKI-DO in a patient with heart failure for the use of ACEI, ARB, spironolactone, NSAID, radiocontrast agents or loop diuretics was as follows: OR: 3.40 (95 % CI = 1.62–7.10), OR: 4 (95 % CI = 0.68–23.51), OR: 2.40 (95 % CI = 1.42–6.10), OR: 3.60 (95 % CI = 0.45–28.56), OR: 1.80 (95 % CI = 1.62–5.10), OR: 3.40 (95 % CI = 1.62–7.10), respectively. Risk of AKI-DO in a patient with hypertension for the use of ACEI, ARB, spironolactone, NSAID, radiocontrast agents or loop diuretics was as follows: OR: 24.15 (95 % CI = 6.59–44.50), OR: 2 (95 % CI = 1.07–3.71), OR: 3.19 (95 % CI = 1.250–2.750), OR: 3.59 (95 % CI = 1.75–4.14), OR: 3.69 (95 % CI = 2.75–5.14), OR: 2.69 (95 % CI = 1.75–4.14), respectively. All of the results are shown in Table 5.

Mortality risk at the end of 20th day after discharge was 0.519 times high. Mortality risk for patients with AKI-DO was increased at the end of 6th month after discharge (HR 1.721, 95 % CI: 1.451–2.043, p < 0.001). Baseline cumulative hazard function is shown in Table 6.

Discussion

Despite significant advances in healthcare technology over the past few years, the incidence of AKI-DO in elderly (65–75 year) and very elderly (>75 year) appears to be on increase. Although there are studies about AKI-DO in general population, data for elderly population are still insufficient. Retrospective studies which were held for AKI-DO in elderly might lead to inadequate or misleading data for short- and long-term clinical results of AKI-DO. Our study differs as it has a prospective design.

Incidence of AKI was 13.6/1000 patients/year for subjects aged 66–69 and 46.9/1000 patients/year for subjects aged older then 85 years [9]. Not enough studies have been carried out to find out incidence of AKI-DO. Furthermore, no study about clinical characteristics, hospital cost and outcome of AKI-DO has been published in our country.

We found the incidence of AKI-DO higher than the previously reported ones [10–12]. This may be related to the different risk factors among different populations.

Few studies in the published literature thoroughly attribute to the cause of AKI. Most common cause of AKI in elderly is acute tubular necrosis (53 %) [13]. However, Kaufman et al. reported that prerenal reasons were the most common etiologic factors of AKI-DO in African-Americans. Gastrointestinal diseases and inadequate oral intake were the most common prerenal factors [10]. In our study, prerenal AKI was the most common type of AKI in both groups. The most striking causes for prerenal AKI were decreased oral intake, vomiting and diarrhea.

Heart failure, CKD, renovascular disease, osteoarthritis and surgical operations are more frequent in elderly people. Therefore, possibility of exposure to iodinated radiocontrast agents, renin–angiotensin system blockers or NSAID is higher [14]. These agents may negatively affect renal hemodynamics and cause a risk for the development of AKI [15, Ross MM, Fisher R, Maclean MJ (2010) End-of-life care for seniors: the development of a national guide. J Palliat Care 16:47–53 Rosner M, Abdel-Rahman E, Williams ME (2010) Geriatric nephrology: responding to a growing challenge. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5:936–942. doi:10.2215/CJN.08731209

Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW (2005) Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 16(11):3365–3370 Chronopoulos A, Cruz DN, Ronco C (2010) Hospital-acquired acute kidney injury in the elderly. Nat Rev Nephrol 6:141–149. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2009.234

Obialo CI, Okonofua EC, Tayade AS, Riley LJ (2000) Epidemiology of de novo acute renal failure in hospitalized African Americans: comparing community-acquired vs hospital-acquired disease. Arch Intern Med 160(9):1309–1313. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.9.1309

Talabani B, Zouwail S, Pyart RD, Meran S, Riley SG, Phillips AO (2014) Epidemiology and outcome of community-acquired acute kidney injury. Nephrology (Carlton) 19(5):282–287. doi:10.1111/nep.12221

Kellum JA, Lameire N, KDIGO AKI Guideline Work Group (2013) Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (Part 1). Crit Care 17(1):204. doi:10.1186/cc11454

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J (2009) A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150(9):604–612. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006

USRDS Annual Report (2013) Acute kidney injury. Am J Kidney Dis 61:e97–e108 Kaufman J, Dhakal M, Patel B, Hamburger R (1991) Community-acquired acute renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis 17:191–198 Liano F, Pascual J (1996) Epidemiology of acute renal failure: a prospective, multicenter, community-based study. Madrid acute renal failure study group. Kidney Int 50(3):811–818 Feest TG, Round A, Hamad S (1993) Incidence of severe acute renal failure in adults: results of a community based study. BMJ 306:481–483 Akposso K, Hertig A, Couprie R, Flahaut A, Alberti C, Karras GA, Haymann JP, Costa De Beauregard MA, Lahlou A, Rondeau E, Sraer JD (2000) Acute renal failure in patients over 80 years old: 25-years’ experience. Intensive Care Med 26:400–406 Coca SG (2010) Acute kidney injury in elderly persons. Am J Kidney Dis 56:122–131. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.034

Ungprasert P, Cheungpasitporn W, Crowson CS, Matteson EL (2015) Individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Intern Med 26(4):285–291. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2015.03.008

Wu X, Zhang W, Ren H, Chen X, **e J, Chen N (2014) Diuretics associated acute kidney injury: clinical and pathological analysis. Ren Fail 36(7):1051–1055. doi:10.3109/0886022X.2014.917560

Chao CT, Tsai HB, Wu CY, Hsu NC, Lin YF, Chen JS, Hung KY (2015) Cross-sectional study of the association between functional status and acute kidney injury in geriatric patients. BMC Nephrol 16:186. doi:10.1186/s12882-015-0181-7

Schissler MM, Zaidi S, Kumar H, Deo D, Brier ME, McLeish KR (2013) Characteristics and outcomes in community-acquired versus hospital-acquired acute kidney ınjury. Nephrology (Carlton) 18(3):183–187. doi:10.1111/nep.12036

Der Mesropian PJ, Kalamaras JS, Eisele G, Phelps KR, Asif A, Mathew RO (2014) Long-term outcomes of community-acquired versus hospital-acquired acute kidney injury: a retrospective analysis. Clin Nephrol 81(3):174–184. doi:10.5414/CN108153

Wonnacott A, Meran S, Amphlett B, Talabani B, Phillips A (2014) Epidemiology and outcomes in community-acquired versus hospital-acquired AKI. CJASN 9(6):1007–1014. doi:10.2215/CJN.07920713

Dreischulte T, Morales DR, Bell S, Guthrie B (2015) Combined use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with diuretics and/or renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in the community increases the risk of acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 88(2):396–403. doi:10.1038/ki.2015.101

Schmitt R, Coca S, Kanbay M, Tinetti ME, Cantley LG, Parikh CR (2008) Recovery of kidney function after acute kidney injury in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2:262–271. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.03.005

Lo LJ, Go AS, Chertow GM, McCulloch CE, Fan D, Ordonez JD, Hsu CY (2009) Dialysis-requiring acute renal failure increases the risk of progressive chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 76:893–899. doi:10.1038/ki.2009.289

Hsu CY, Chertow GM, McCulloch CE, Fan D, Ordoñez JD, Go AS (2009) Nonrecovery of kidney function and death after acute on chronic renal failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4:891–898. doi:10.2215/CJN.05571008

Bucaloiu ID, Kirchner HL, Norfolk ER, Hartle JE 2nd, Perkins RM (2012) Increased risk of death and de novo chronic kidney disease following reversible acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 81:477–485. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.405

Albright RC, Smelser JM, McCarthy JT, Homburger HA, Bergstralh EJ, Larson TS (2000) Patient survival and renal recovery in acute renal failure: randomized comparison of cellulose acetate and polysulfone membrane dialyzers. Mayo Clin Proc 75:1141–1147 Wald R, Quinn RR, Luo J, Li P, Scales DC, Mamdani MM, Ray JG (2009) University of Toronto acute kidney ınjury research group. Chronic dialysis and death among survivors of acute kidney injury requiring dialysis. JAMA 302:1179–1185. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1322

Tomlinson LA, Wheeler DC (2014) Chronic kidney disease and the uremic syndrome. In: Johnson RJ, Feehally J, Floege J (eds) Comprehensive clinical nephrology, 5th edn. Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp 942–948 Dasta JF, Kane-Gill SL, Durtsch AJ, Pathak DS, Kellum JA (2008) Costs and outcomes of acute kidney injury (AKI) following cardiac surgery. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23:1970–1974. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfm908

Kerr M, Bedford M, Matthews B, O’Donoghue D (2014) The economic impact of acute kidney injury in England. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29(7):1362–1368. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfu016

Bedford M, Stevens PE, Wheeler TW, Farmer CK (2014) What is the real impact of acute kidney injury? BMC Nephrol 15:95. doi:10.1186/1471-2369-15-95

References

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Turgutalp, K., Bardak, S., Horoz, M. et al. Clinical outcomes of acute kidney injury develo** outside the hospital in elderly. Int Urol Nephrol 49, 113–121 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-016-1431-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-016-1431-8