Abstract

Using the market values of audit partners’ houses as a measure of their personal wealth, we find that wealthier U.S. partners provide higher-quality audits, as evidenced by fewer material restatements, fewer material SEC comment letters, and higher audit fees. A battery of falsification tests shows that these findings are not driven by the matching of wealthier partners with clients with higher financial reporting quality. Our additional analyses suggest two explanations: greater personal wealth both incentivizes partners to exert more effort in delivering high-quality audits and reveals partners’ audit competence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper investigates whether an audit partner’s personal wealth explains audit quality. Although international studies using individual fixed effects approaches consistently demonstrate the significant influence of individual audit partners on audit quality (e.g., Gul et al. 2013; Aobdia et al. 2015; Knechel et al. 2015), the specific partner attributes responsible for these observed differences remain elusive. Demographic and professional attributes (e.g., age and busyness) offer limited explanatory power for differences in audit quality. Furthermore, there is often a lack of a theoretical foundation supporting their potential effects (Lennox and Wu 2018). Considering the critical role audits play in financial markets, there exists a pressing need, as emphasized by multiple research calls, to explore more impactful and theoretically substantiated partner attributes influencing audit quality (e.g., Aobdia 2019a; Francis 2023).

This study proposes a financial characteristic by which to infer U.S. audit partners’ quality: their personal wealth. We posit that partner wealth explains audit quality for two reasons. First, wealth directly incentivizes audit partners to conduct better audits, because wealthier partners have more to lose when an audit failure occurs (the more-to-lose explanation). In a seminal study, Dye (1993) notes that “an auditor chooses a higher-quality audit as his wealth increases because his wealth is in effect a bond he posts to ensure the performance of an audit of acceptable quality” (p. 893). Even under limited liability partnerships (LLPs)—the most common legal form for today’s audit firms—negligent partners risk not only their within-firm assets but also personal assets, such as their houses (Watts and Zimmerman 1986; Lennox and Li 2012; Lennox and Wu 2018). In a report submitted to the U.S. Department of Treasury, the Big Six audit firms assert that a “partner's personal assets may be vulnerable in lawsuits arising out of audit work in which he or she personally participated” (CAQ 2008, p. 30).

Second, partner wealth indirectly reveals the partners’ competence because more competent partners presumably receive higher pay (the signaling competence explanation). For example, Deloitte emphasizes this connection by saying, “Our partner performance management and remuneration process creates a strong link between audit quality and partner remuneration” (Deloitte & Touche LLP 2015, p. 24). Recent research also shows that audit quality is an important metric in audit firms’ internal evaluations, which primarily determine partner compensation (Coram and Robinson 2017; Knechel et al. 2013; Bik et al. 2021).

We measure partner wealth using the partner’s house value, which, in the United States, is one of a few publicly available pieces of their individual financial information. House values reasonably reflect U.S. partners’ wealth because they usually exceed the partners’ contributed capital in audit firms and represent the partners’ largest personal assets (CAQ 2008). Also, a national survey by the Census Bureau shows, in the accounting profession, a correlation of 75% between house value and personal net worth (2016 U.S. Survey of Income and Program Participation).

We identify 2,287 partners’ houses using property tax records from the LexisNexis Public Record Database and obtain the houses’ market value from Zillow. We find that a U.S. partner’s house value is, on average, $1.34 million, which is more economically significant than the partner’s average contributed capital in the audit firm ($0.4 million) (CAQ 2008). There is substantial variation in house value across partners, ranging from $0.66 million in the 25th percentile to $1.67 million in the 75th percentile.

Our main finding is that wealthier partners provide better audits. After controlling for location and other partner characteristics (e.g., workload and experience), we find that clients audited by a partner with a higher house value are less likely to have materially misstated financial statements and to receive a material comment letter from the SEC. These clients also pay higher audit fees. The economic magnitude appears significant: a one-standard-deviation increase in partner house value is associated with a 0.7 percentage point decrease in restatements (which corresponds to 22% of the unconditional mean), a 0.6 percentage point decrease in SEC comment letters (14% of the unconditional mean), and a 2.5% increase in audit fees. Our falsification tests suggest that the results do not reflect a systematic match between wealthier partners and clients with higher financial reporting quality. We also find that excluding the state-level homestead exemptions from partners’ house values does not affect our inference.Footnote 1

To differentiate the more-to-lose and signaling competence explanations in the association between partner house values and audit quality, we divide partners’ house values into two components. The first, total gains or losses on housing, represents the sum of realized gains or losses from houses sold and unrealized gains or losses from houses owned by a partner. The second component, investment, is calculated as the difference between a partner’s house value and that person’s total gains or losses on housing. This reflects a partner’s investment in houses using income from sources outside the housing market.

We posit that partners’ total gains or losses from the housing market are relatively exogenous to their audit competence, for several reasons. First, individual house prices tend to fluctuate more idiosyncratically than stock prices (Case and Shiller 1989; Giacoletti 2021). Second, buyers have to transact entire houses rather than in shares, inhibiting risk diversification. Third, the limited presence of arbitrageurs in housing markets suggests that house prices can deviate from their fundamental values for extended periods.Footnote 2 These market frictions imply that a partner’s higher competence does not necessarily lead to greater returns from the housing market, particularly when owning only one or two properties. Lastly, using gains or losses on housing as an exogenous variation in wealth is consistent with recent studies (e.g., Aslan 2022; Bernstein et al. 2021; Dimmock et al. 2021).

We show that gains or losses on housing are largely independent of partner competence. Specifically, we find no significant association between gains or losses on housing and partner characteristics typically indicative of pay level: Big Four affiliation, client portfolio size, industry expertise, and office leadership. Furthermore, there is no significant correlation between gains or losses on housing and non-audit fees paid by clients. To the extent that these characteristics capture partner competence, our findings suggest that total gains or losses on housing offer a variation in partner wealth that is reasonably exogenous to that person’s competence.

We find that total gains or losses on housing are positively associated with all three audit quality measures, suggesting that a relatively exogenous increase in partner wealth leads to an improvement in audit quality. These results support our first argument and support Dye’s (1993) theoretical prediction that auditor wealth serves as collateral for ensuring audit quality.

To provide empirical evidence for the second argument—that house value reveals the partner’s audit competence—we focus on the second house value component: partners’ investment in houses using income from sources outside the housing markets. We find that a partner’s investment in houses is positively associated with all partner characteristics that indicate pay level (i.e., Big Four affiliation, client portfolio size, industry expertise, and office leadership). Additionally, a partner’s investment in houses is significantly associated with non-audit fees paid by clients, consistent with the notion that a competent partner generates more revenue from cross-selling services to afford more expensive houses. Both findings contrast with those of the first component (i.e., gains or losses on housing) and suggest that the second component of a partner’s house value contains information about that partner’s competence.

We find that partners’ investment in houses using income from sources outside the housing markets is significantly associated with all three audit quality measures, consistent with the notion that more competent partners provide better audits. More importantly, we find that both gains or losses on housing and investment in houses explain audit quality when they are included in the model simultaneously. This suggests that the more-to-lose and signaling competence arguments coexist and jointly contribute to the association between partners’ house values and audit quality. Although distinctly different, the two explanations have observationally equivalent effects for investors who aim to discern the quality of U.S. partners.

Our study closely relates to two others. One is by Dekeyser et al. (2021), who investigate the association between partners’ economic incentives and audit quality using a sample of 67 Belgian audit partners. Although they show a positive association between audit quality and partners’ equity-to-asset ratios, they attribute this association to a negative impact of partner debt—rather than a positive effect of partner equity—on audit quality. Furthermore, they find that a partner’s equity is not significantly associated with audit quality, leading to inconclusive evidence on whether partners’ wealth affects audit quality. Our study answers their call for studying the effect of partner wealth in the context of publicly traded firms and a high-litigation-risk environment.

The other is by Lennox and Li (2012), who find no significant change in audit quality after U.K. audit firms switch from general partnerships to LLPs. Because the switch changes the risk exposure of nonnegligent partners, the study speaks to the effect of mutual monitoring among partners, which, according to Watts and Zimmerman (1986), is the second way partnerships affect audit quality. Our study complements the work of Lennox and Li (2012) by focusing on the first explanation proposed by Watts and Zimmerman (1986)—the audit partners’ use of personal assets as collateral for their actions. We conclude that greater personal assets do improve audit quality.

This paper contributes to the literature on the impact of individual partners on audit quality. Answering calls for more research on the determinants of partner quality, we show that partner wealth has an economically significant influence on audit quality, consistent with the theoretical prediction of Dye (1993). Our study also contributes to a growing literature on the impact of personal wealth. Recent research documents that variations in housing wealth impact job performance of equity analysts, innovative workers, and financial advisors (Bernstein et al. 2021; Aslan 2022; Dimmock et al. 2021). Our study adds to this line of literature by showing that house wealth also affects audit partners’ behavior.

Last, our study contributes to the current debate regarding the value of disclosing audit partner names in the United States. When the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) proposed disclosing engagement partners’ identities, the U.S. audit industry strongly opposed the idea, arguing that partner identification would heighten their litigation risk without offering tangible benefits (Deloitte & Touche LLP 2009, 2012). Our finding that partners’ house values explain audit quality implies that partner identities, if revealed, could offer investors a new way to assess audit quality. This aligns with the PCAOB’s broad goal of enhancing transparency in the audit process.

2 Literature review and hypothesis development

Building on the management style literature (e.g., Bamber et al. 2010), audit research using international data finds that audit partners have a persistent style effect across engagements (e.g., Gul et al. 2013; Cameran et al. 2022; Knechel et al. 2015). For example, using the U.K. data, Cameran et al. (2022) find that partner fixed effects dominate both audit firm and office fixed effects and account for 25% of the explained variation in audit quality. As a result, Francis (2023, p. 11) asserts: “The relative importance of audit-related factors in explaining audit outcomes is the opposite of what I previously believed: partner-led engagement teams are an important factor—maybe the most important—in explaining audit outcomes.”

In examining which partner characteristic influences audit styles, research has focused on demographic factors, such as gender, age, and IQ, as well as professional attributes like busyness and experience (e.g., Aobdia et al. 2021; Burke et al. 2019; Kallunki et al. 2019; Lee et al. 2019). Yet these factors account for only a small fraction of the variation in partner styles (Gul et al. 2013; Aobdia 2019a). Recognizing the partner attributes’ limited explanatory power for their overall large effect on audit quality, researchers have stressed the need for more partner-level studies, especially ones grounded in “a strong underlying theory” (Lennox and Wu 2018, p. 23).

We propose that partner wealth explains audit quality through two channels. In the first, we posit that partners with more to lose are incentivized to provide higher-quality audits, as suggested by Dye (1993). Under LLPs, audit partners’ personal assets are vulnerable to litigation risks from their engagements (Lennox and Wu 2018). This risk is significant, as neither the audit firms’ internal equity nor their external professional liability insurance is likely to suffice in the face of catastrophic litigation (U.S. Chamber of Commerce 2007; U.S. Treasury 2008). There is historical evidence of audit partners losing all their personal assets in lawsuits. Stone (1994, p. 33) notes that several partners declared bankruptcy following the 1990 collapse of Laventhol & Horwath. Similarly, Pacelle and Dugan (2002) report that many Arthur Andersen partners feared the loss of their personal assets when the firm dissolved in 2002, despite Andersen being an LLP.

The PCAOB partner identity disclosure rule in 2016 may further increase personal litigation risk. Analyzing litigation cases from 2012 to 2021 from Audit Analytics, we observe a rise in lawsuits against partners. Specifically, audit partners were named defendants in 18% (4/22) of lawsuits from 2017 to 2021—the five years post the PCAOB’s partner identification rule—compared to only 2% (1/42) from 2012 to 2016. For instance, in 2019, Joshua Abrahams, a former PWC partner who audited Mattel Inc., was sued by Mattel’s investors. In 2020, INTREorg Systems sued its audit firm, LBB & Associates, and its managing partner, Carlos Lopez, for improper professional conduct and failure to disclose an SEC investigation. These cases underscore the potential escalation of partners’ personal liability concerns. (See Appendix C for details.)

In the second channel, partner wealth may imperfectly indicate the partner’s competence. Research indicates that audit quality is a key metric in audit firms’ internal evaluations, influencing partners’ compensation. For example, Knechel et al. (2013) find that Swedish audit partners’ pay is negatively impacted by going concern reporting errors. Coram and Robinson (2017) observe a formal link between partners’ compensation and audit quality in Australian audit firms. Similarly, Bik et al. (2021) show that Dutch audit firms commonly assign partners to competence classes. Partners who do not meet expectations in internal quality reviews face a monetary penalty and risk being demoted to a lower class, which harms their long-run pay. In the United States, neither partner compensation nor internal evaluations are publicly available. Therefore house value could reasonably proxy for a partner’s compensation and unobserved competence.

Nevertheless, there are reasons why wealthier partners might not deliver better audits. For example, U.S. partners have been highly motivated for audit quality, due to the firm’s internal control system, career concerns, and professional integrity. Thus their personal wealth may add little to their motivation. Wealthier partners might also earn more income by increasing fee revenues than by prioritizing high audit standards, making it less clear whether a partner’s wealth should be positively associated with audit quality. In an alternative form, our hypothesis is:

-

H1: Ceteris paribus, partners’ wealth is positively associated with audit quality.

3 Data and sample construction

We use three data sources. The first is the PCAOB Form AP, which contains information about partners’ names and client engagements. The second is the LexisNexis Public Record Database. This database collects property tax records for more than 1,000 U.S. counties in 46 states, the District of Columbia, and the Virgin Islands, and deed transfer records for more than 600 U.S. counties in 46 states and the District of Columbia. It also contains professional license information from 22 states. The third is Zestimate on Zillow.com, which is Zillow’s estimate of a house’s market value based on its home valuation model. As the biggest U.S. online real estate website, Zillow captured 57% of the online real estate traffic as of 2017 (Feeney 2016; Lu 2018). After multiple algorithm updates over the years, Zestimate is currently calculated based on a neural network-based model that incorporates numerous data fields, including square footage, number of bedrooms, tax assessment, prior sales, historical listing prices, comparable homes in the area, days listed on the market, and market conditions (Zillow 2021). Recent research finds that individuals heavily rely on Zestimate to reach the final sales price (Lu 2018; Yu 2021).

We begin our sample construction with all partner identities disclosed in the PCAOB Form AP as of June 2020. We exclude employee benefit plans and investment companies and restrict the sample to U.S.-based clients audited by U.S. audit firms. After merging the data with Compustat and Audit Analytics, our initial sample consists of 13,903 firm-year observations audited by 2,912 unique audit partners from 2016 to 2019. We first search for each partner in the LexisNexis Public Record Database. When a name search yields multiple individuals in the database, we collect more of the partner’s personal information (e.g., age and current state location) from professional websites (e.g., LinkedIn) to narrow the range. We also cross-check professional licenses in the LexisNexis database, when available, to confirm that the individual is a CPA. Once we identify the partner in the database, we collect that person’s current houses and previous houses from deed and property tax records. To calculate the partner’s total gains or losses from the housing markets, we manually extract the price at which the partner bought or sold each house. We collect Zestimate for current houses from Zillow as of early 2019. (See an example in Appendix B.)Footnote 3

To compare Zestimate with other market estimates, we randomly select 200 houses in our sample and searched their estimated market value from Realtor.com and Redfin.com, the two other most popular real estate websites. We find that the correlation between Zestimate and the estimated market value from Realtor (Redfin) is 97% (96%), suggesting that there would be little difference if we measured partners’ house value using alternative sources. Nevertheless, we caveat that Zestimate may not perfectly reflect a house’s market value. For example, it may not fully account for home improvements.

We drop 614 partners whose house values were missing because either the houses could not be found in the LexisNexis database or the house values are unavailable on Zillow. We drop five partners for whom we could not determine gains or losses on housing, due to missing house purchase prices, four partners whose total house values were below $10,000 (likely due to erroneous records), and two partners with missing age or gender information. Overall we obtain 2,287 partners’ house values. These partners audit 10,771 firm-year observations from 2016 to 2019, accounting for 77% of our initial client sample. These firm-years also account for 78% (72%) of total audit fees (market value) of the initial sample. We report our sample selection in Table 1.

Table 2 shows that 64% of the 2,287 partners in our final sample work for the Big Four auditors, 12% are industry specialists, 18% are female, and 12% are local office leaders. On average, the clients they serve have total assets of $845 million. These partners themselves average 25.8 years of experience. About two-thirds of the partners own one house, with an average value of $1.34 million per partner. House value varies substantially across partners—from $0.66 million at the 25th percentile to $1.67 million at the 75th percentile.

We also break down partners’ house value by partners’ gender, Big Four affiliation, industry expertise, and office leadership. At the univariate level, we find that male and female partners own houses of similar value, but partners with Big Four affiliation, industry expertise, and office leadership positions have significantly higher house values (p-value < 0.01). When we break down partners by state, we find that those in California and Washington have the most expensive houses, while those in Louisiana and Nebraska have the cheapest. These statistics underscore the importance of controlling for locations when comparing partners’ house values.

We also conduct a multivariate regression to explore which partner characteristics are associated with house value.Footnote 4 We report the results in Table 3. We find that partners from Big Four firms and those with greater workloads (more and larger clients), industry expertise, local office leadership positions, and longer tenure have higher house values. These findings are consistent with previous research showing that partners with these characteristics have higher compensation (Knechel et al. 2013).

4 Research design

We examine the association between the partner’s house value and audit quality using the following regression model:

We measure audit quality using material restatements, material comment letters from the SEC, and audit fees. We use restatements and SEC comment letters because they are ranked as the top two audit quality indicators by audit partners and senior managers (Christensen et al. 2016). Both are output-based external indicators for low-quality audits and thus are less likely to correlate with the client firm’s business fundamentals and operating environment.

Although restatements have been shown to be associated with audit deficiencies identified by the PCAOB, the SEC, and private lawsuits (Aobdia 2019b; Rajgopal et al. 2021), Lennox and Li (2020) suggest that not all restatements indicate egregious audit failures that impose litigation risk or threaten partners’ income and reputation. Specifically, they find that audit firms are more likely to be sued only if the restatement involves 1) fictitious revenue, 2) fictitious or overvalued assets, 3) fictitious reductions of expenses, or 4) undervalued expenses or liabilities. All these deficiencies result in either inflated earnings or inflated shareholders’ equity. Therefore, to precisely capture audit failures, we exclude revision restatements that do not downwardly affect earnings or shareholders’ equity. Restatement, our first audit quality measure, equals 1 if the firm restates earnings or shareholders’ equity downward or issues an Item 4.02 nonreliance restatement and 0 otherwise. We include all nonreliance restatements because they are severe restatements that require the reissuance of previous financial statements.Footnote 5

The SEC’s comment letters frequently predate its enforcement actions, which target individual partners more frequently than audit firms (Feroz et al. 1991; Johnston and Petacchi 2017; Kedia et al. 2018). Following Czerney et al. (2019) and Ahn et al. (2020), we use SEC comment letters related to annual financial statements as the second proxy for audit quality. Cunningham and Leidner (2022) suggest that, because many SEC comment letters are not material, do not involve accounting issues, or are closed after a single response from the company, receiving one does not necessarily indicate an audit failure. Following their suggestions, we use only comment letters 1) that involve at least one accounting issue, 2) for which the company files at least two correspondence letters, and 3) that are not solely related to extension requests, duplicate issues, cover letters, or phone conversations. We downloaded both restatements and SEC comment letters in December 2022.

Last, we use audit fees to complement the two output-based audit quality measures. The literature (e.g., Aobdia 2019b) shows a high correlation between audit hours and audit fees in the United States, so Audit Fees is a continuous input-based measure that primarily captures audit efforts (Lobo and Zhao 2013).

We define House Value as the total market value, in millions of dollars, of all houses owned by an audit partner. If wealthier partners provide better audits, we expect β in Eq. (1) to be negative (positive) when the dependent variable is Material Restatements or Material Comment Letters (Audit Fees). The literature that uses data from outside the United States finds mixed evidence on whether partner characteristics, such as gender and experience, are associated with audit quality. Recent studies using U.S. data find that few partner characteristics are associated with audit quality in the United States (e.g., Lee et al. 2019; Baugh et al. 2022; Aobdia et al. 2021). Nonetheless, to mitigate the concern about omitted correlated variables, we control for partner characteristics examined in the literature, including workload, industry expertise, office leadership, experience, and gender.

When examining the relationship between partners’ house values and audit quality, it is important to control for location because 1) house value is largely determined by it and 2) audit quality may vary with it. Following Francis et al. (2005), Reichelt and Wang (2010), and Swanquist and Whited (2015), we collect auditors’ states and cities from Audit Analytics and convert them to micropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) using the U.S. Census Bureau’s MSA cross-map. We control for the MSA fixed effects in Model (1).

Following prior studies (e.g., Bills et al. 2016), we include a large number of client and auditor characteristics. For the restatement and the SEC comment letter model, our control variables include Size, Leverage, ROA, Loss, Total Accruals, M&A, Issuances, Foreign, Internal Control, Big 4, Client Importance, Auditor Tenure, Office Size, Office Industry Specialist, and NAS Ratio. For the audit fees model, our control variables include Size, Leverage, ROA, Loss, Current Ratio, Receivable + Inventory, Number of Segments, M&A, Issuances, Foreign, Internal Control, Big 4, Going Concern, Auditor Tenure, Office Size, and Office Industry Specialist. Last, we include two-digit SIC industry and year fixed effects. We omit Big 4 when we include audit firm fixed effects.

5 Results on partners’ house value and audit quality

5.1 Main results

In this section, we examine the association between a partner’s house value and audit quality. First, we report the descriptive statistics of all variables used in the test in Table 4. Our sample consists of 10,771 firm-year observations from 2016 to 2019. About 3% of firms in our sample have a subsequent material restatement, and 4% of firms subsequently receive a material comment letter from the SEC related to annual financial statements. Clients on average pay $2.4 million in audit fees.

We report the regression results based on restatements and SEC comment letters in Table 5. We find that a higher House Value is significantly associated with a lower likelihood of restatement and a lower chance of receiving an SEC comment letter (p-value < 0.01 for all specifications). To determine the economic magnitude, we first calculate the standard deviation of house values after controlling for all fixed effects (i.e., industry, year, audit firm, and MSA) in Model (1). This within-fixed effect standard deviation is 0.81, slightly smaller than the unconditional sample standard deviation of 1.02. Using the within-FE variation, we find that a one-standard-deviation increase in house value is associated with a 0.65 (= 0.008 × 0.81 × 100) percentage point lower likelihood of restatements (equal to 22% of the unconditional mean of restatements) and a 0.57 (= 0.007 × 0.81 × 100) percentage point lower likelihood of SEC comment letters (equal to 14% of the unconditional mean of SEC comment letters).

As for the other partner characteristics, none are associated with restatements, and only gender is associated with SEC comment letters. These results are consistent with the literature showing that common partner characteristics do not explain audit quality in the United States (e.g., Aobdia et al. 2021; Baugh et al. 2022). In particular, we find that partner experience is not associated with audit quality, consistent with the findings of Lee et al. (2019). Regarding other control variables, we find that large clients are more likely to restate and receive a comment letter from the SEC, possibly due to their greater complexity. Big Four audit firms are associated with fewer restatements, consistent with the notion that larger audit firms provide higher audit quality (Becker et al. 1998; Lennox and Pittman 2010; Jiang et al. 2019).

We report the regression results based on audit fees in Table 6. We find that House Value is significantly associated with higher audit fees. Specifically, a one-standard-deviation increase in House Value is associated with an increase of 2.5% (= 0.81 × 0.031) in audit fees. This economic magnitude is comparable to those in prior studies on the impacts of individuals on audit fees. For example, Abbott et al. (2003) find that an audit committee member with accounting expertise is associated with a 7.0% increase in audit fees, and Bills et al. (2017) find that a new CEO is associated with a 5.7% increase in audit fees. Regarding control variables, we find that the coefficients on most are statistically significant with the expected sign. The adjusted R2 is 91% in the model with all four types of fixed effects, suggesting that the unexplained portion of audit fees is small.

5.2 Client-partner matching: falsification tests and client assignments

An alternative explanation for our main findings is that, because partners are not randomly assigned to clients, wealthier partners could be systematically assigned to ones with higher financial reporting quality or that are less likely to be targeted by the SEC. To mitigate this concern, we conduct the following falsification tests.

Immaterial annual restatements and quarterly restatements

If wealthier partners are systematically assigned to clients with better reporting quality, we expect that the partner’s house value will also be associated with financial reporting failures. To identify these failures, we use immaterial annual restatements and quarterly restatements. Lennox and Li (2020) suggest that annual restatements that do not harm earnings or shareholders’ equity reflect financial reporting failures but not audit failures. Also, because quarterly financial statements are not audited, quarterly restatements reflect low financial reporting quality but not low audit quality. We report the results in Panel A of Table 7. We find that partners’ house values are not associated with immaterial annual restatements or quarterly restatements. These findings mitigate the concern that our main findings are driven by the matching of wealthier partners to clients with higher financial reporting quality.

SEC comment letters other than material accounting-related ones

Receiving a comment letter may reflect more attention paid by the SEC to a given client firm, so the association between SEC comment letters and the partner’s house value may be driven by wealthier partners being assigned to clients that are less likely to be targeted by the SEC. If so, we expect the partner’s house value to be associated with SEC comment letters other than the ones we use to construct the audit quality measure. This would include comment letters that are unrelated to annual financial statements, comment letters that relate to annual financial statements but do not involve accounting issues, and immaterial comment letters that are closed after a single response from the company. We report the results in Panel A of Table 7. We find that partners’ house values are not associated with these SEC comment letters, corroborating the inference that partners with higher house values provide better audits.

Pseudo client-years at t-6

If our main findings are driven by a systematic match between partners and clients, we expect to observe similar positive associations between the partner’s house value and audit quality measures, even when the partners are not incumbent. Exploiting the five-year mandatory partner rotation, we construct a preceding sample consisting of the same clients as our main sample but at year t-6. The audit partner for a given client in year t-6 must differ from the one in our sample period, even though we cannot identify who they were. We chose t-6 instead of t-5 because the incoming partner may shadow the outgoing partner in the latter’s last year on the engagement (Dodgson et al. 2020) and because the outgoing partner works harder in last year to protect her or his reputation (Lennox et al. 2014). We report the results in Panel B of Table 7. We do not find that the house value of the incumbent partner is associated with restatements, comment letters, or audit fees in the pseudo period, corroborating our inference that our main results are attributable to the incumbent partner rather than client assignment.

We also investigate whether wealthier partners are more likely to be assigned to riskier clients. The results in Appendix Table A1 reveal mixed associations between partner wealth and client risk. Nonetheless, our inferences remain the same, even if we control for more client risk characteristics.

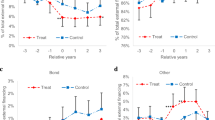

5.3 Cross-sectional analyses on litigation risk and client complexity

In this section, we examine how two client characteristics—litigation risk and complexity—affect the relationship between partner wealth and audit quality. First, we analyze how this relationship varies with a client’s litigation risk. If wealthier partners work harder due to litigation concerns, then the impact of partner wealth on audit quality should be more pronounced for clients with higher litigation risk. To assess this, we construct a litigation risk measure following Kim and Skinner (2012, Model (2) in Table 7) and partition the sample, based on the median of the measure, into low- and high-risk groups.Footnote 6 Panel A of Table 8 presents the results. We find that the difference in coefficients on House Value between the low- and high-litigation-risk groups is statistically significant when the dependent variable is SEC comment letters or audit fees. Thus the association between partner wealth and audit quality strengthens for high-litigation-risk clients in two of the three audit quality tests. This cross-sectional test indirectly supports the more-to-lose channel.

Second, we examine whether the relationship between partner wealth and audit quality varies with client complexity. If wealthier partners are more competent, their impact on audit quality should strengthen for more complex clients. To assess this, we construct a client complexity measure that incorporates both operational and financial reporting complexity. We first rank all clients into deciles by total assets (a proxy for operational complexity) and by the Accounting Reporting Complexity score developed by Hoitash and Hoitash (2018), respectively. Then we partition the sample into the low- and high-complexity groups based on the median of the ranking sum. Panel B of Table 8 presents these results. We find that the difference in coefficients on House Value between the low- and high-complexity groups is statistically significant when the dependent variable is SEC comment letters and audit fees. Thus the association between partner wealth and audit quality strengthens for high-complexity clients in two of the three audit quality tests. These cross-sectional tests provide some indirect evidence for the signaling competence explanation.

5.4 Additional tests

Homestead exemption

In the United States, a homestead exemption is a legal provision that protects a homeowner’s primary residence from being seized to pay off debts. The protection amount varies by state and is set by state laws. The portion of a partner’s house value that exceeds the threshold is at risk in litigation and thus serves as collateral for the partner’s actions. Table A2 of the online appendix reports the state-specific homestead exemption from Dahle (2022). Using these exemption thresholds, we break down partners’ house values into two variables: Assets at Risk and Assets Protected. Assets at risk equals the portion of a partner’s house value above the exemption threshold. For the few states that offer unlimited protection (e.g., Florida), Assets at Risk is set to zero. Assets Protected equals a partner’s house value protected by (i.e., below) the state homestead exemption. We run Model (1) using these two variables instead of House Value and report the results in Table A3 of the online appendix. Assets at Risk is significantly associated with all three audit quality measures, suggesting that excluding the state homestead exemption does not change our inferences. In contrast, Assets Protected is not associated with any audit quality measure.

Nonreliance (4.02 item) restatements and excluding firm-year observations that the SEC is unlikely to have reviewed

Nonreliance (4.02 item) restatements are perceived as severe audit failures. To test the robustness of our findings using restatements, we rerun Model (1) with only nonreliance restatements as the dependent variable. The results in Column (1) in Table A7 of the online appendix show that our inferences regarding partners’ house values remain unchanged.

One concern with using the SEC comment letters as an audit quality measure is that the SEC does not review annual financial statements for all firms every year, and the firm-year observations not reviewed by the SEC mechanically receive no comment letters. Because the data showing which firms are reviewed is not publicly available, we follow Cassell et al. (2013) and exclude observations where the firm did not receive a comment letter in the current year but did receive one in at least one of the past two years. Our inference remains the same. (See Column (2) in Table A7 of the online appendix.) This approach may be too conservative because it assumes that the SEC reviews each firm only once every three years, when in fact over 50% of public firms are reviewed in a typical year (SEC 2017).

Controlling for partners’ location and other fixed effects

In our main results, we have controlled for audit offices’ metropolitan statistical area (MSA) fixed effects. Alternatively, we could control for audit offices’ city fixed effects. We could further interact either MSA fixed effects or city fixed effects with year fixed effects. We rerun Model (1) under these fixed effect specifications and report the results in Panels A, B, and C in Table A9 of the online appendix. Our inferences remain the same.

In addition, because audit partners might not live in the same MSA as their office location, we also control for partners’ home addresses’ MSA fixed effects, instead of their offices’ MSA fixed effects, and report the results in Panel D of Table A9. We further include both the partners’ home address MSA fixed effects and office MSA fixed effects and report the results in Panel E of Table A9. Our inferences remain the same.

We also conduct other additional analyses. These tests include examining whether wealthier partners are more frequently assigned to riskier clients, conducting robustness tests using alternative audit quality measures, using entropy balancing, exploring whether the findings vary across Big Four versus other firms, and addressing the concerns related to partners with missing house values. We report the results and related discussion in the online appendix.

6 Separating the more-to-lose explanation from the signaling competence explanation

We posit that both the more-to-lose and signaling competence explanations offer insight into the positive association between a partner’s house value and audit quality. To separate the explanations, we break down a partner’s house value into two parts: 1) cumulative gains or losses on housing (Gains or Losses on Housing) and 2) investment in houses using income from sources outside the housing markets (Investment). Gains or Losses on Housing equals the sum of the differences between the sale price and the purchase price (i.e., realized gain or loss) of each house sold by the partner and the difference between the market value and the purchase price (i.e., unrealized gain or loss) of each house currently owned by the partner. Investment equals House Value minus Gains or Losses on Housing. This variable also equals the purchase price of a partner’s current houses minus realized gains or losses from that person’s past house sales. The idea is that a partner may use gains from selling an old house to buy the next house. By subtracting the realized gains or losses from the new house’s purchase price, we obtain a cleaner measure of a partner’s investment in housing using income from outside the housing markets. We consider cumulative gains or losses on housing to be a relatively exogenous variation in partner wealth. The remaining portion of house values—Investment—likely signals a partner’s competence by capturing that person’s income from the audit firm.

A partner’s cumulative gains or losses on housing are likely to be exogenous to the partner’s audit competence for two reasons. First, the statistics on the home purchases and sales in our sample indicate that partners purchase houses primarily for personal use rather than for investment purposes. Partners, on average, have purchased a total of three houses and owned each of them for approximately eight years.Footnote 7 The timing of these purchases may correspond to significant life events, such as marriage, family changes, career advancements, and job relocations.

Second, even if some partners purchase houses for speculation, the literature suggests that changes in individual house prices are unpredictable. For instance, Cheng et al. (2014) show that even experienced asset managers on Wall Street failed to anticipate the 2007 housing price crash. Giacoletti (2021) highlights substantial price dispersion even for houses with nearly identical characteristics in the same area, with idiosyncratic risk accounting for 45% to 70% of individual house price variances (due to house illiquidity). This finding is consistent with Case and Shiller’s (1989) argument that the idiosyncratic component is the most substantial determinant of an individual house’s capital gain variance. Because 97% of audit partners hold no more than three houses, it is nearly impossible for most partners to reduce the idiosyncratic risk through diversification. Overall it seems reasonable to believe that partners’ gains or losses on housing constitute a wealth source independent of their audit competence.

We report in Table 4 that, on average, a partner’s cumulative gains or losses on housing are $480,000—a nontrivial amount that could influence their behavior. The amount varies considerably across partners, from $120,000 in the 25th percentile to $620,000 in the 75th percentile. The interquartile difference of $500,000 exceeds the combined price of two average U.S. houses.Footnote 8 A partner’s investment in housing, on average, is $910,000. Although the mean is larger for Investment than for Gains or Losses on Housing, there is relatively less variation in Investment across partners: its coefficient of variation (i.e., the ratio of standard deviation to the mean) is 0.78, compared with 1.27 for Gains or Losses on Housing.

We conduct two tests to evaluate whether the two components of House Value represent distinct constructs. First, we investigate whether they relate to the partner characteristics that capture competence (i.e., Big Four affiliation, client portfolio size, industry expertise, and office leadership). We report the results in Panel A of Table 9. We find that partners’ cumulative gains or losses on housing are not associated with any of these characteristics, while partners’ investments in houses are positively associated with all of them. The contrasting results support the notion that gains or losses on housing, the first house-value component, are exogenous to partner competence, while investment in houses, the second house-value component, primarily captures partner competence.

Second, we examine whether a partner’s gains or losses on housing and investment in housing help explain non-audit fees paid by clients. More competent partners should be able to sell more non-audit services. However, if an increase in partner wealth means the partner has more to lose in the event of audit failure, it should incentivize that partner to provide higher-quality audits but not to sell more non-audit services. Therefore our empirical prediction is that gains or losses on housing is not, but investment in houses is, associated with non-audit fees.

We regress the natural logarithm of non-audit fees on Gains or Losses on Housing and Investment after controlling for the same variables as in Table 6 (i.e., audit fee tests). We report the results in Panel B of Table 9. Consistent with our prediction, we find that a partner’s gains or losses on housing are not associated with non-audit fees but her investment in houses is. These contrasting results further support the inference that the two house-value components represent distinct constructs: Gains or losses on Housing reflects an exogenous variation in partner wealth, while Investments reflects partner competence.

Next we examine the association between each of the two house-value components and audit quality. We report the results in Table 10. We find that both a partner’s gains or losses on housing and investment in housing are positively associated with all three audit quality measures (p-value < 0.05). The coefficient estimates and statistical significance of these two variables barely change when the variables are included in the model together, implying that their underlying constructs do not overlap. Overall these findings and those in Table 8 suggest that both the more-to-lose and signaling competence explanations help illuminate the association between a partner’s house value and audit quality.

We conduct a series of robustness tests and provide the details in the online appendix. In Table A12, we control for partners’ average house purchase price and holding period, as gains or losses on housing might be influenced by initial purchase prices and ownership duration. In Table A13, we include house purchase year fixed effects, as the purchasing timing may reflect a partner’s ability (to time the markets). In Table A14, we decompose gains or losses on housing into the market-driven and house-specific components. We find that gains or losses driven by the local housing markets are associated with two of the three audit quality measures. Finally, in Table A15, we separate house values into unrealized gains or losses and purchase prices. Across all these tests, our inferences about the relationship between partners’ housing gains or losses and audit quality measures remain consistently robust.

7 Conclusion

We provide empirical evidence that audit partners’ wealth explains audit quality. As the largest personal assets for most partners, houses should reasonably capture the variation in personal wealth across U.S. audit partners. Using house value as a proxy for partner wealth, we find that wealthier partners provide better audits, as reflected in a lower likelihood of material restatements, a lower likelihood of material comment letters from the SEC, and higher audit fees. A series of falsification tests show that our results are unlikely to be explained by the matching of wealthier partners to clients with higher financial reporting quality. We also conduct a battery of robustness tests and continue to find a significant association between partners’ house values and audit quality.

We posit that both the more-to-lose and signaling competence explanations provide insight into the positive association between a partner’s house value and audit quality. The former explanation suggests that wealthier partners have more incentives to conduct high-quality audits because they have more to lose in the event of audit failure. The latter one suggests that a partner’s house value indirectly reveals audit competence, as more competent partners are likely to be paid more and thus can afford pricier houses.

To differentiate between these explanations, we separate a partner’s house value into two components: 1) cumulative gains or losses on housing and 2) investment in houses using income from sources outside the housing markets. We first conduct two tests, which show that gains or losses on housing are unlikely to reflect partners’ competence. Then we find that the partners’ gains or losses on housing are associated with higher audit quality—evidence consistent with the more-to-lose explanation. In addition, we find that partners’ investment in houses is significantly associated with partner characteristics that capture her competence. After controlling for these characteristics, we find that investment in houses is also associated with audit quality—evidence consistent with the signaling competence explanation.

We caveat that house value imperfectly proxies for partner wealth, so measurement error may attenuate the wealth effect on audit quality. In particular, because current mortgage balances are not publicly available, we cannot deduct a partner’s mortgage balance from that person’s house value to calculate net assets.Footnote 9 However, based on the 2016 U.S. Survey of Income and Program Participation, the correlation between asset value and equity value for houses owned by accounting professionals is as high as 92%. This suggests that minimal measurement error in our proxy. Our inferences also may not generalize to partners who do not own houses, since our sample only includes homeowners. Nevertheless, our partner sample is larger than those of most concurrent U.S. partner studies (e.g., Baugh et el. 2021; Burke et al. 2019; Lee et al. 2019; Pittman et al. 2021). We call for future research that proposes better ways to measure partner wealth and re-examine its association with audit quality.

Notes

State homestead exemptions are legal provisions that protect a portion of an individual’s primary residence value from creditors.

Shiller (2015) states: “In housing, the smart money has relatively little voice.”.

We started this project in 2018, so the sample period was 2016 to 2017. Because Zillow did not provide historical Zestimate back then, we collected only the current Zestimate (as of early 2019). However, by the time we extended our sample period (to cover fiscal years 2018 and 2019) in 2022, Zillow had made historical Zestimate available. Therefore, for new partners’ houses, we could still collect their 2019 Zestimates to maintain consistency.

One may wonder if a partner’s house value reflects family size. Due to privacy regulations, information about individuals’ family size is generally not publicly available. In a subsample of partners who voluntarily disclose their family size, however, we find no association between house values and family size. (See Table A16 of the online appendix.).

For the observations with a missing risk measure, we classify them based on whether the client is in a high-litigation-risk industry classified in Kim and Skinner (2012).

Seventy-five percent of partners’ current houses are bought after 12 years in their careers. Since the average track to partnership takes about 12 years, this suggests that most acquired their current homes after being promoted to partners.

The average U.S. house price in 2019 is $226,000 (Zillow).

LexisNexis contains information on the initial mortgage contracts when a partner purchased a house, but it does not include the current balance. Current balances are not calculable due to subsequent prepayment and refinance activities.

References

Abbott, L.J., S. Parker, G.F. Peters, and K. Raghunandan. 2003. The association between audit committee characteristics and audit fees. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 22 (2): 17–32.

Ahn, J., R. Hoitash, and U. Hoitash. 2020. Auditor task-specific expertise: The case of fair value accounting. The Accounting Review 95 (3): 1–32.

Aobdia, D. 2019. Why shouldn’t higher I.Q. audit partners deliver better audits? A discussion of Kallunki, Kallunki, Niemi and Nilsson (2019). Contemporary Accounting Research 36 (3): 1404–1416.

Aobdia, D. 2019b. Do practitioner assessments agree with academic proxies for audit quality? Evidence from PCAOB and internal inspections. Journal of Accounting and Economics 67 (1): 144–174.

Aobdia, D., C.J. Lin, and R. Petacchi. 2015. Capital market consequences of audit partner quality. The Accounting Review 90 (6): 2143–2176.

Aobdia, D., S. Siddiqui, and A. Vinelli. 2021. Heterogeneity in expertise in a credence goods setting: Evidence from audit partners. Review of Accounting Studies 26 (2): 1–37.

Aslan, H. 2022. Personal Financial Distress, Limited Attention. Journal of Accounting Research 60 (1): 97–128.

Bamber, L.S., J. Jiang, and I.Y. Wang. 2010. What’s my style? The influence of top managers on voluntary corporate financial disclosure. The Accounting Review 85 (4): 1131–1162.

Baugh, M., N.J. Hallman, and S.J. Kachelmeier. 2022. A matter of appearances: How does auditing expertise benefit audit committees when selecting auditors? Contemporary Accounting Research 39 (1): 234–270.

Becker, C.L., M.L. DeFond, J. Jiambalvo, and K.R. Subramanyam. 1998. The effect of audit quality on earnings management. Contemporary Accounting Research 15 (1): 1–24.

Bernstein, S., T. McQuade, and R.R. Townsend. 2021. Do household wealth shocks affect productivity? evidence from innovative workers during the great recession. Journal of Finance 76 (1): 57–111.

Bik, O, Bouwens J., Knechel W.R, and Zou, Y., 2021. Performance Management and Compensation for Audit Partners. Working Paper.

Bills, K.L., L.M. Cunningham, and L.A. Myers. 2016. Small audit firm membership in associations, networks, and alliances: Implications for audit quality and audit fees. The Accounting Review 91 (3): 767–792.

Bills, K.L., L.L. Lisic, and T.A. Seidel. 2017. Do CEO succession and succession planning affect stakeholders’ perceptions of financial reporting risk? Evidence from audit fees. The Accounting Review 92 (4): 27–52.

Burke, J.J., R. Hoitash, and U. Hoitash. 2019. Audit partner identification and characteristics: Evidence from U.S. Form AP filings. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 38 (3): 71–94.

Cameran, M., D. Campa, and J.R. Francis. 2022. The relative importance of auditor characteristics versus client factors in explaining audit quality. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance 37 (4): 751–776.

Case, K.E., and R.J. Shiller. 1989. The efficiency of the market for single family homes. American Economic Review 79 (1): 125–137.

Cassell, C.A., L.M. Dreher, and L.A. Myers. 2013. Reviewing the SEC’s review process: 10-K comment letters and the cost of remediation. The Accounting Review 88 (6): 1875–1908.

Census. 2019. Net worth of households: 2016 https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2019/demo/p70br-166.html. Accessed 01 Jan 2020.

Center for Audit Quality (CAQ), 2008. Report of the major public company audit firms to the department of the treasury advisory committee on the audit profession.

Cheng, I.H., S. Raina, and W. **ong. 2014. Wall Street and the housing bubble. American Economic Review 104 (9): 2797–2829.

Christensen, B.E., S.M. Glover, T.C. Omer, and M.K. Shelley. 2016. Understanding audit quality: Insights from audit professionals and investors. Contemporary Accounting Research 33 (4): 1648–1684.

Coram, P.J., and M.J. Robinson. 2017. Professionalism and performance incentives in accounting firms. Accounting Horizons 31 (1): 103–123.

Cunningham, L.M., and J.J. Leidner. 2022. The SEC filing review process: A survey and future research opportunities. Contemporary Accounting Research 39 (3): 1653–1688.

Czerney, K., D. Jang, and T.C. Omer. 2019. Client deadline concentration in audit offices and audit quality. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 38 (4): 55–75.

Dahle, J. 2022. The White Coat Investor's Guide to Asset Protection: How to Protect Your Life Savings from Frivolous Lawsuits and Runaway Judgments. WCI Intellectual Property.

Dekeyser, S., A. Gaeremynck, W.R. Knechel, and M. Willekens. 2021. The impact of partners’ economic incentives on audit quality in Big 4 partnerships. The Accounting Review 96 (6): 129–152.

Deloitte & Touche LLP 2009. Re: Concept Release on Requiring the Engagement Partner to Sign the Audit Report. PCAOB Rulemaking Docket Matter No. 029.

Deloitte & Touche LLP 2012. Re: Proposed Standard: Improving the Transparency of Audits PCAOB Rulemaking Docket Matter No. 029.

Deloitte & Touche LLP 2015. Transparency Report. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/au/Documents/audit/deloitte-au-audit-transparency-report-2015-180915.pdf. Accessed 01/03/2020

Dimmock, S.G., W.C. Gerken, and T. Van Alfen. 2021. Real estate shocks and financial advisor misconduct. Journal of Finance 76 (6): 3309–3346.

Dodgson, M.K., C.P. Agoglia, G.B. Bennett, and J.R. Cohen. 2020. Managing the auditor-client relationship through partner rotations: The experiences of audit firm partners. The Accounting Review 95 (2): 89–111.

Dye, R.A. 1993. Auditing standards, legal liability, and auditor wealth. Journal of Political Economy 101 (5): 887–914.

Feeney 2016. Zillow snags more internet market share than ever. May 19. https://www.inman.com/2016/05/19/zillow-snags-internet-market-share-ever/. Accessed 02/03/2020.

Feroz, E.H., K. Park, and V.S. Pastena. 1991. The financial and market effects of the SEC’s accounting and auditing enforcement releases. Journal of Accounting Research 29 (3): 107–142.

Francis, J.R. 2023. Going big, going small: A perspective on strategies for researching audit quality. The British Accounting Review 55 (2): 1–15.

Francis, J.R., and P.N. Michas. 2013. The contagion effect of low-quality audits. The Accounting Review 88 (2): 521–552.

Francis, J.R., K. Reichelt, and D. Wang. 2005. The pricing of national and city-specific reputations for industry expertise in the US audit market. The Accounting Review 80 (1): 113–136.

Gaver, J.J., and S. Utke. 2019. Audit quality and specialist tenure. The Accounting Review 94 (3): 113–147.

Giacoletti, M. 2021. Idiosyncratic risk in housing markets. Review of Financial Studies 34 (8): 3695–3741.

Guan, Y., L.N. Su, D. Wu, and Z. Yang. 2016. Do school ties between auditors and client executives influence audit outcomes? Journal of Accounting and Economics 61 (2–3): 506–525.

Gul, F.A., D. Wu, and Z. Yang. 2013. Do individual auditors affect audit quality? Evidence from archival data. The Accounting Review 88 (6): 1993–2023.

Hoitash, R., and U. Hoitash. 2018. Measuring accounting reporting complexity with XBRL. The Accounting Review 93 (1): 259–287.

Jiang, J., I.Y. Wang, and K.P. Wang. 2019. Big N auditors and audit quality: New evidence from quasi-experiments. The Accounting Review 94 (1): 205–227.

Johnston, R., and R. Petacchi. 2017. Regulatory oversight of financial reporting: Securities and Exchange Commission comment letters. Contemporary Accounting Research 34 (2): 1128–1155.

Kallunki, J., J.P. Kallunki, L. Niemi, H. Nilsson, and D. Aobdia. 2019. IQ and audit quality: Do smarter auditors deliver better audits? Contemporary Accounting Research 36 (3): 1373–1416.

Kedia, S., U. Khan, and S. Rajgopal. 2018. The SEC’s enforcement record against auditors. Journal of Law, Finance, and Accounting 3 (2): 243–289.

Kim, I., and D.J. Skinner. 2012. Measuring securities litigation risk. Journal of Accounting and Economics 53 (1–2): 290–310.

Knechel, W.R., L. Niemi, and M. Zerni. 2013. Empirical evidence on the implicit determinants of compensation in Big 4 audit partnerships. Journal of Accounting Research 51 (2): 349–387.

Knechel, W.R., A. Vanstraelen, and M. Zerni. 2015. Does the identity of engagement partners matter? An analysis of audit partner reporting decisions. Contemporary Accounting Research 32 (4): 1443–1478.

Lee, H.S., A.L. Nagy, and A.B. Zimmerman. 2019. Audit partner assignments and audit quality in the United States. The Accounting Review 94 (2): 297–323.

Lennox, C., and B. Li. 2012. The consequences of protecting audit partners’ personal assets from the threat of liability. Journal of Accounting and Economics 54 (2–3): 154–173.

Lennox, C., and B. Li. 2020. When are audit firms sued for financial reporting failures and what are the lawsuit outcomes? Contemporary Accounting Research 37 (3): 1370–1399.

Lennox, C., and J. Pittman. 2010. Big Five audits and accounting fraud. Contemporary Accounting Research 27 (1): 209–247.

Lennox, C., and X. Wu. 2018. A review of the archival literature on audit partners. Accounting Horizons 32 (2): 1–35.

Lennox, C., X. Wu, and T. Zhang. 2014. Does mandatory rotation of audit partners improve audit quality? The Accounting Review 89 (5): 1775–1803.

Li, L., B. Qi, G. Tian, and G. Zhang. 2017. The contagion effect of low-quality audits at the level of individual auditors. The Accounting Review 92 (1): 137–163.

Lobo, G.J., and Y. Zhao. 2013. Relation between audit effort and financial report misstatements: Evidence from quarterly and annual restatements. The Accounting Review 88 (4): 1385–1412.

Lu, G. 2018. Learning from online appraisal information and housing prices. Available at SSRN 3489522.

Pacelle, M., and Dugan, I.J. 2002. Andersen partners consult lawyers about limited-liability protection. Wall Street Journal, April 2.

Pittman, J., Stein S.E, and Valentine D.F. 2021. The Importance of Audit Partners’ Risk Tolerance to Audit Quality. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3311682. Accessed 02/03/2020.

Rajgopal, S., S. Srinivasan, and X. Zheng. 2021. Measuring audit quality. Review of Accounting Studies 26 (2): 559–619.

Reichelt, K.J., and D. Wang. 2010. National and office-specific measures of auditor industry expertise and effects on audit quality. Journal of Accounting Research 48 (3): 647–686.

SEC. 2017. Agency Financial Report. https://www.sec.gov/files/sec-2017-agency-financial-report.pdf. Accessed 02/03/2020.

Shiller, R. The housing market still isn’t rational. The New York Times. July 24, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/26/upshot/the-housing-market-still-isnt-rational.html. Accessed on 02/17/2023.

Stone, M.L. 1994. Incorporated CPA firms. Journal of Accountancy 177 (3): 33–34.

Swanquist, Q.T., and R.L. Whited. 2015. Do clients avoid “contaminated” offices? The economic consequences of low-quality audits. The Accounting Review 90 (6): 2537–2570.

U.S. Chamber of Commerce. 2007. Commission on the Regulation of U.S. Capital Markets in the 21st Century Report and Recommendations available at https://www.uschamber.com/assets/archived/images/legacy/reports/0703capmarkets_summ.pdf. Accessed 02/2020.

U.S. Treasury. 2008. Final Report of the Advisory Committee on the Auditing Profession to the US Department of the Treasury. The Department of the Treasury.

Watts, R.L., and Zimmerman J.L. 1986. Positive Accounting Theory. Prentice-Hall Inc.

Yu, S. 2021. Algorithmic Outputs as Information Source: The Effects of Zestimates on Home Prices and Racial Bias in the Housing Market. Available at SSRN 3584896.

Zillow, 2021. Zillow Launches New Neural Zestimate, Yielding Major Accuracy Gains https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/zillow-launches-new-neural-zestimate-yielding-major-accuracy-gains-301312541.html. Assessed 02/01/2023.

Acknowledgements

The paper was previously titled “Inferring Quality of U.S. Audit Partners from Their Houses.” We express our gratitude to Paul Fischer, the editor, and the anonymous reviewer for valuable feedback. We extend our thanks to Andrew Acito, Musaib Ashraf, Ken Bills, Lauren Cunningham, Ivy Feng, Feng Guo, Chris Hogan, Bin Ke (discussant), Robert Knechel, Clive Lennox, Edward Li, Ling Lisic, Brandon Lock, Monica Neamtiu, Jeff Pittman, Joe Schroeder, Min Shen, Sarah Stein, Marshall Vance, Isabel Wang, Qian Wang, Olena Watanabe, and to workshop participants at Baruch College, Purdue, Virginia Tech, CUHK Accounting Research Conference, Iowa State, Renmin University of China, and Dongbei University of Finance & Economics for their comments. Additionally, we are thankful for the research assistance provided by Noah Blake, Nick Krupa, Nina Hernandez, Geneva Hernandez, and Michael Friedman, and for the financial support from the Fisher School of Accounting, the Luciano Prida, Sr. term professorship, and the Eli Broad Professorship. All authors contributed equally to this research. Any errors are ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Variable Definitions

Variable | Definition [Source] |

|---|---|

Dependent Variables | |

Material Restatements | 1 if the client either restates earnings or shareholders’ equity downward or files a nonreliance (Item 4.02) restatement for its annual financial statements of year t; 0 otherwise [Audit Analytics] |

Material Comment Letters | 1 if the client receives a material comment letter related to the annual financial statements of year t from the SEC; 0 otherwise. Following Cunningham and Leidner (2022), we classify a comment letter as material if 1) it involves at least one accounting issue; 2) the company files at least two correspondence letters; and 3) it is not solely related to extension requests, duplicates issues, cover letters, or phone conversation. [Audit Analytics] |

Log of Audit Fees | The natural logarithm of audit fees paid by a client in dollars [Audit Analytics] |

Log of Non-audit Fees | The natural logarithm of (1 + non-audit fees paid by a client in dollars) [Audit Analytics] |

Immaterial Restatements | 1 if the client restates its annual financial statements of year t but the restatement is not a nonreliance (Item 4.02) restatement and does not adjust earnings or shareholders’ equity downward; 0 otherwise [Audit Analytics] |

Quarterly Restatements | 1 if the client restates at least one of its quarterly financial statements in year t but not its annual financial statement of year t; 0 otherwise [Audit Analytics] |

Other Comment Letters | 1 if the client receives a comment letter not related to its annual financial statements of year t or an immaterial comment letter related to the annual financial statements of year t from the SEC; 0 otherwise [Audit Analytics] |

Audit Partner Characteristics | |

House Value | The sum of market value of houses owned by a partner (in millions of dollars) [LexisNexis, Zillow] |

Gains or Losses on Housing | The total gains or losses from all of a partner’s house transactions (in millions of dollars). It equals the sum of the differences between the sale price and the purchase price of each house sold and the difference between the market value and the purchase price of each house currently owned. [LexisNexis, Zillow] |

Investment | House Value minus Gains or Losses on Housing. It reflects a partner’s investment in his or her current houses using income from outside the housing markets (which is most likely pay) |

Workload | The natural logarithm of the sum of total assets of clients audited by the partner in year t [Compustat] |

Specialist | 1 if the partner is among the top three partners with the largest market share (in total assets) or has a market share of greater than 5% in the client’s industry; 0 otherwise [Audit Analytics] |

Office Leader | 1 if the partner is an office leader; 0 otherwise [LinkedIn] |

Female | 1 if the partner is female; 0 otherwise [LexisNexis, LinkedIn] |

Experience | The number of years since the partner’s work start year. When the partner’s start year is unavailable on LinkedIn, we use age minus 22. [LexisNexis, LinkedIn] |

Client and Auditor Characteristics | |

|---|---|

Total Assets | The natural logarithm of total assets [Compustat] |

Leverage | The sum of debt in current liabilities and long-term debt, divided by total assets [Compustat] |

ROA | Income before extraordinary items divided by total assets [Compustat] |

Loss | 1 if the client’s income before extraordinary items is less than zero; 0 otherwise [Compustat] |

Total Accruals | Income before extraordinary items minus operating cash flows, divided by total assets [Compustat] |

Current Ratio | Current assets divided by current liabilities; we set it to 0 if it is missing [Compustat] |

Inventory + Receivables | The sum of accounts receivable and inventory, divided by total assets [Compustat] |

Number of Segments | The natural logarithm of the number of all segments; 0 if the client has no segment data [Compustat Segment] |

M&A | 1 if the client has an acquisition that contributed to sale; 0 otherwise [Compustat] |

Issuances | 1 if the client has long-term debt issuances or sales of stock in year t; 0 otherwise [Compustat] |

Foreign | 1 if the client has income from foreign operations; 0 otherwise [Compustat] |

Internal Control | 1 if the management’s internal control report discloses a material weakness in year t; 0 otherwise [Audit Analytics] |

Big 4 | 1 if the client is audited by a Big Four audit firm; 0 otherwise [Audit Analytics] |

Going Concern | 1 if the client received a going concern opinion in year t; 0 otherwise [Audit Analytics] |

Client Importance | Audit fees from the client divided by the sum of audit fees for the same audit office in year t [Audit Analytics] |

Auditor Tenure | The number of consecutive years of being audited by the current audit firm [Audit Analytics] |

Office Size | The natural logarithm of (1 + the sum of audit fees) for an audit office in year t [Audit Analytics] |

Office Industry Specialist | 1 if the audit office has the largest market share (in total assets) in the client’s industry in the same city and has more than 10% greater market share than its closest competitor; 0 otherwise [Audit Analytics] |

NAS Ratio | The ratio of total non-audit fees to audit fees [Audit Analytics] |

Office NAS Emphasis | The ratio of an audit office’s non-audit fees to its total fees. In the partner-level analysis, we take the average for each partner. [Audit Analytics] |

Appendix 2: An Example of Data Collection

A partner is disclosed in the PCAOB Form AP.

Audit Firm | Partner Name | Partner ID |

|---|---|---|

A Big Four firm | M. XXX | YYYYYY |

We locate the property tax records in 2018 in the LexisNexis Public Record Database.

Then we search his address in Zillow.

House Value of M. XXX is $1,095,228.

Appendix 3: U.S. Audit Partners Sued

To demonstrate U.S. partners’ personal litigation risk, we download all the private lawsuits against U.S. auditors from 2012 to 2021 from Audit Analytics. We restrict the sample to those classified as accounting malpractice. We find that, in recent years, partners are more frequently sued by investors. Specifically, audit partners were named as defendants in 18% (4/22) of the lawsuits that occurred after the PCAOB’s partner identification rule became effective. These statistics show that partners may face higher personal litigation risk now than before. The historical lack of lawsuits against individual partners does not necessarily mean that partners are not concerned about personal liability nowadays.

Year | Number of lawsuits | Audit partners as defendants |

|---|---|---|

2012 | 15 | 0 |

2013 | 7 | 0 |

2014 | 6 | 0 |

2015 | 10 | 1 |

2016 | 4 | 0 |

Five years before the PCAOB partner identification rule | 42 | 1 |

2017 | 2 | 0 |

2018 | 4 | 0 |

2019 | 4 | 2 |

2020 | 6 | 2 |

2021 | 2 | 0 |

Five years after the PCAOB partner identification rule | 22 | 4 |

We list the five lawsuits that involve at least one audit partner below.

Date | Clients | Audit Firm | Partner(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

2015–2011 | Tauriga Sciences Inc | Cowan Gunteski & Co | William Meyler |

2019–2007 | Breitling Oil & Gas Corp.; Breitling Royalties Corp.; Breitling Energy Corp | Rothstein Kass & Co | Brian Matlock |

2019–2012 | Mattel Inc | PriceWaterHouseCoopers LLP | Joshua Abrahams |

2020–2007 | INTREorg Systems Inc | LBB & Associates Ltd | Carlos Lopez |

2020–2012 | Pioneer Bank | Teal Becker & Chiaramonte CPAs PC | Pasquale M Scisci; Vincent Commisso |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, J.X., He, S. & Wang, K.P. Partner wealth and audit quality: evidence from the United States. Rev Account Stud (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-024-09828-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-024-09828-6