Abstract

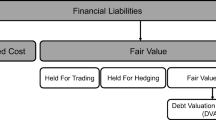

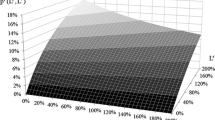

Under SFAS No. 159, U.S. firms can measure debt liabilities at fair value, which results in recognition of unrealized gains and losses from debt valuation adjustments (DVA) when a firm’s own credit risk changes. Critics have raised concerns about the counterintuitive income consequences of DVA; that is, when a firm’s credit risk increases (i.e., bad news), debt values decrease, and resulting DVA gains increase the firm’s income (i.e., good news), and vice versa. In this paper, we examine the relation between market valuation and DVA gains and losses, conditioning on the level of unrecognized asset value (UAV). We develop a model to demonstrate the mitigating effect of UAV on the relation between equity returns and DVA. We show that, while the association between equity returns and DVA is positive when the level of UAV is low, the association decreases and eventually turns negative with increasing levels of UAV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

SFAS No. 157 and 159 are now incorporated into the FASB Accounting Standards Codification in Topics 820–10 and 825–10, respectively.

See SFAS No. 157 Appendix C47 for further discussion on the counterintuitive nature of DVA (FASB 2006).

For example, in 2008, Goldman Sachs reported a pretax profit of $2.3 billion, approximately half of which represented DVA gains. In an even more extreme case, DVA gains changed what would have been Morgan Stanley’s 2008 $3.3 billion loss into a $1.7 billion gain. In contrast, as the banking sector recovered in 2009, Citigroup recognized a $4.2 billion DVA loss on the strengthening of its own creditworthiness.

Chris Lucas (Group Finance Director of Barclays), “Banks are one step away from greater transparency.” The Financial Times, Letters to the Editor (November 14, 2011). https://www.ft.com/content/a53627b2-0c88-11e1-8ac6-00144feabdc0. Accessed December 21, 2017.

In the “Basis for Conclusions” section of ASU 2016–01, the FASB acknowledged that it was responding to stakeholder complaints about the counterintuitive nature of DVA gains and losses: “Many stakeholders consider recognizing a gain due to a decrease in credit standing to be potentially misleading because an entity often lacks the ability to realize those gains” (Paragraph BC100).

We thank the reviewer for this insight.

For example, SFAS No. 107, Disclosures about Fair Value of Financial Instruments (December 1991); SFAS No. 115, Accounting for Certain Investments in Debt and Equity Securities (May 1993); and SFAS No. 133, Accounting for Derivative Instruments and Hedging Activities (June 1998), among others.

One of the FASB’s stated goals for SFAS No. 159 was to make it easier for firms to match the fair value of financial assets with related liabilities and thereby provide firms the opportunity to mitigate earnings volatility without having to apply complex hedge accounting provisions (see paragraph 1 of SFAS No. 159). Consistent with this purpose, many firms’ stated reason for electing the fair value option for liabilities was to align the accounting for such liabilities with the firm’s risk management practices and to mitigate volatility in reported earnings. For example, in its 2007 annual report, JPMorgan Chase & Co. disclosed the following: “The Firm’s fair value elections were intended to mitigate the volatility in earnings that had been created by recording financial instruments and the related risk management instruments on a different basis of accounting or to eliminate the operational complexities of applying hedge accounting (page 119).” Chung et al. (2017) investigate the effects of SFAS No. 159 on earnings volatility.

Since DVA is recognized as a component of net income during our sample period, DVA will influence equity valuation through net income, whereas in the post-ASU 2016–01 period, it will be through OCI.

We develop our model with a focus on the association between market value of equity and DVA gains and losses. A bank’s asset portfolio risk (and thus its own credit risk) can vary throughout the year, not just when DVA amounts are released to the market. As we are interested in the overall value-relevance of DVA and not simply the market’s reaction to the release of DVA amounts with quarterly earnings, we focus on the association between returns and DVA over a long (e.g., quarterly) window, rather than market reaction to DVA over a short (e.g., three-day) window. We assume that an efficient market impounds the effects of the firm’s credit risk in returns over the fiscal quarter in which these changes occur. Given that the accounting systems for quarter t produce meaningful measures of the firm’s own credit risk for that quarter, the reported DVA and market return for quarter t should demonstrate a contemporaneous association.

In this context, “dividends” refers to net dividends, meaning the difference between actual dividend payout and equity financing or liquidation activities (e.g., share issuance and share repurchase).

For the post-ASU 2016–01 period, when DVA gains and loses become a part of OCI, similar models can be constructed by decomposing OCI into pre-DVA OCI and DVA. The effect of UAV on the value-relevance of DVA will be the same as what we demonstrate in our current models.

Our assumption of a negative relation between asset risk and asset value will not hold under the case of pure asset substitution (i.e., when only unsystematic asset risk changes). For example, a firm can sell $100 of risk-free assets and buy $100 of risky assets. This substitution changes the risk profile of the assets but not their value, while at the same time decreasing the value of debt (and thus increasing the value of equity since Equity = Assets – Liabilities). We thank the reviewer for suggesting this example.

The literature on the impact of bond rating changes on common stock returns has two conflicting theories. Some researchers (Griffin and Sanvicente 1982; Holthausen and Leftwich 1986; Glascock et al. 1987) argue that credit rating changes provide incremental information to the stock market, because of the embedded internal information from company management. In contrast, Pinches and Singleton (1978) argue that credit rating changes merely summarize public information. However, Choy et al. (2006) find abnormal negative returns on the day of a credit rating downgrade, consistent with the incremental information theory.

The Bank Holding Act of 1956 regulates the activities of bank holding companies. We follow the act, defining a bank holding company as a company that controls one or more banks. FR Y-9C reports are made available by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago on its website. As we describe shortly, the vast majority of our sample firms are depository institutions that are classified as traditional commercial banks under SIC codes, whereas the remainder must have at least some involvement in banking activities, since they fall under the regulatory purview of the Federal Reserve and file FR Y9-C reports.

SFAS No. 159 is effective for fiscal years beginning after November 15, 2007, with early adoption permitted. As a result, BHCs adopted SFAS No. 159 either in the first quarter of 2008 or in the first quarter of 2007 if they chose early adoption. We hand-collected each BHC’s adoption date in its Form 10-K. 50% of BHCs in our sample are early adopters. Untabulated analyses show that our results hold for both early adopters and regular adopters.

We use the CRSP-FRB link provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/banking_research/datasets.html) to link FR Y-9C data and CRSP data.

Because the fair value option is made on an instrument-by-instrument basis upon inception of the instrument (or upon adoption of SFAS No. 159 if inception was earlier), a bank may not necessarily have liabilities recorded at fair value during every quarter in the sample period (although most of our sample banks do). For example, a firm may not choose the fair value option for any of its existing liabilities in the quarter in which it adopts SFAS No. 159 but adopt the fair value option for new liabilities as they arise in a later quarter.

Both SFAS No. 107 and FSP No. SFAS 107–1 are now contained within the FASB Accounting Standards Codification Topic 825–10.

We use the 2005–2006 period immediately prior to SFAS No. 159 adoption. We also run a robustness check using a two-year rolling-window for the computation of earnings volatility. Our results are largely unaffected.

News of credit risk change may come before the quarter-end reporting of DVA gains and losses, and market reaction to credit risk change may subsume the market reaction to later DVA reporting. However, the purpose of our paper is to examine how DVA information is associated with market valuation over DVA reporting periods, not the timeliness of the DVA reporting itself. Therefore, we choose a quarterly window for our return measure, instead of a three-day window typical in event studies.

The Federal Reserve requires BHCs to file FR Y-9C reports within 40 calendar days after a quarter end (45 calendar days in the case of the fourth quarter). We note that 97% of BHCs in our sample announce earnings within the FR Y-9C reporting deadline. Thus we believe that the market will be aware of updated financial information by the FR Y-9C reporting deadline. Our results remain qualitatively unchanged if we shift the return window 40 days, rather than 22 days (untabulated).

Dhaliwal et al. (1999) study OCI after SFAS No. 130, Reporting Comprehensive Income, was effective in 1997 and find limited evidence on its value-relevance, although they note that financial institutions and available-for-sale securities adjustments are an exception to this. Chambers et al. (2007) provide evidence that OCI is priced on a dollar-for-dollar basis in the post-SFAS No. 130 period, as predicted by economic theory for transitory income items.

Leone et al. (2017) discuss the relative merits of trimming versus winsorizing. On one hand, winsorizing might induce measurement error in observations in its attempt to mitigate the effect of influential observations. On the other hand, trimming tends to impart a bias towards zero in OLS coefficients. We rerun our main regression tests after winsorizing, rather than trimming, our sample and find that our main results on variation in the relation between DVA and returns with the level of UAV continue to hold.

The two alternative UAV measures, the UAV estimated from Beaver et al.’s (1989) model and the market UAV (defined as the market value of equity less its book value), have comparable descriptive statistics (untabulated).

We also examine the correlation between DVA and changes in UAV (untabulated) and find a negative correlation of −0.124 (p < 0.01). In addition, as an external validity check, we examine the correlations of changes in credit default spread (CDS, a proxy of credit risk) with DVA and with changes in UAV. CDS increases with firms’ perceived credit risk. Consistent with prior research (Merton 1974; Barth et al. 2008), we find a positive correlation of 0.372 (p < 0.01) between changes in CDS and DVA and a negative correlation of −0.245 (p < 0.01) between changes in CDS and changes in UAV (untabulated). The opposite correlations suggest an offsetting relation between DVA and changes in UAV resulting from changes in credit risk.

We report two goodness of fit statistics for the estimation of the first-stage equation, pseudo R2 and the area under the ROC (receiver operating characteristic) curve. The latter is the estimated probability that the model ranks a randomly selected bank that elects the fair value option higher than a randomly selected bank that does not elect the fair value option. Random guessing generates an area under the ROC curve equal to 0.5, and perfect prediction generates 1. Hosmer et al. (2013) suggest that a model with an area under the ROC curve of 0.70–0.80 (above 0.80) is acceptable (excellent).

To compare our results with Chung et al.’s (2017), we also run a regression of quarterly size-adjusted returns on DVA and pre-DVA income, using only the 191 nonzero DVA observations in our sample. The coefficient on pre-DVA income is significantly positive (p < 0.05), which is consistent with the findings of Chung et al. (2017). However, unlike Chung et al. (2017), we do not find a positive relation between quarterly size-adjusted returns and DVA.

We decomposed our nonzero DVA subsample into two further subgroups of positive DVA observations and negative DVA observations, and we find insignificant results in both groups, suggesting that neither group is driving our overall results. The lack of significance within both groups is likely due to a lack of power, given the relatively small subgroup sizes. Additionally, we rerun our main regression tests on our full sample using a three-way interaction with a new variable indicating whether DVA is negative, and we find an insignificant coefficient on the three-way interaction, while the main effect and the two-way interaction continue to hold, suggesting a lack of a significant difference in valuation of DVA gains versus DVA losses.

References

Ahmed, A., Takeda, C., & Thomas, S. (1999). Bank loan loss provisions: a reexamination of capital management, earnings management and signaling effects. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 28(1), 1–25.

Barth, M., Beaver, W., & Landsman, W. (1996). Value-relevance of banks’ fair value disclosures under SFAS No 107. The Accounting Review, 71(4), 513–537.

Barth, M., Beaver, W., & Landsman, W. (1998). Relative valuation roles of equity book value and net income as a function of financial health. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 25(1), 1–34.

Barth, M., Hodder, L., & Stubben, S. (2008). Fair value accounting for liabilities and own credit risk. The Accounting Review, 83(3), 629–664.

Beaver, W. (1968). The information content of annual earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting Research, 6, 67–92.

Beaver, W., & Ryan, S. (2009). Risky debt, mixed-attribute accounting, and the identification of conditional conservatism. Working paper. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1477528 Accessed 2010.

Beaver, W., Eger, C., Ryan, S., & Wolfson, M. (1989). Financial reporting, supplemental disclosures, and bank share prices. Journal of Accounting Research, 27(2), 157–178.

Begley, J., Chamberlain, S., & Li, Y. (2006). Modeling goodwill for banks: A residual income approach with empirical tests. Contemporary Accounting Research, 23(1), 31–68.

Blankespoor, E., Linsmeier, T., Petroni, K., & Shakespeare, C. (2013). Fair value accounting for financial instruments: Does it improve the association between bank leverage and credit risk? The Accounting Review, 88(4), 1143–1177.

Burne, K. (2011). How weakening credit strengthens banks’ results—and vice versa. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052970204346104576637042309269366. Accessed December 21, 2017.

Chambers, D., Linsmeier, T., Shakespeare, C., & Sougiannis, T. (2007). An evaluation of SFAS No. 130 comprehensive income disclosures. Review of Accounting Studies, 12(4), 557–593.

Chen, C., Kohlbeck, M., & Warfield, T. (2008). Timeliness of impairment recognition: Evidence from the initial adoption of SFAS 142. Advances in Accounting, 24(1), 72–81.

Choy, E., Gray, S., & Ragunathan, V. (2006). Effect of credit rating changes on Australian stock returns. Accounting and Finance, 46(5), 755–769.

Chung, S., Lobo, G., & Ow Yong, K. (2017) Valuation implications of FAS 159 reported gains and losses from fair value accounting for liabilities. Working Paper. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2978730. Accessed 2017 Sept.

Dhaliwal, D., Subramanyam, K., & Trezevant, R. (1999). Is comprehensive income superior to net income as a measure of firm performance? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 26(1–3), 43–67.

Financial Accounting Standards Board. (2006). Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 157: Fair value measurements. Norwalk: FASB.

Financial Accounting Standards Board. (2007). Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 159: The fair value option for financial assets and financial liabilities—Including an amendment of FASB Statement No. 115. Norwalk: FASB.

Financial Accounting Standards Board. (2013). Proposed Accounting Standards Update—Financial Instruments—Overall (Subtopic 825–10): Recognition and measurement of financial assets and financial liabilities. Norwalk: FASB.

Fontes, J., Panaretou, A., & Peasnell, K. (2018). The impact of fair value measurement for bank assets on information asymmetry and the moderating effect of own credit risk gains and losses. The Accounting Review, 93(6), 127–147.

Glascock, J., Davidson, W., & Henderson, G. (1987). Announcement effects of Moody’s bond rating changes on equity returns. Quarterly Journal of Business and Economics, 26(3), 67–78.

Griffin, P., & Sanvicente, A. (1982). Common stock returns and rating changes: A methodological comparison. The Journal of Finance, 37(1), 103–119.

Heckman, J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161.

Hodder, L., Hopkins, P., & Wahlen, J. (2006). Risk-relevance of fair-value income measures for commercial banks. The Accounting Review, 81(2), 337–375.

Holthausen, R., & Leftwich, R. (1986). The effect of bond rating changes on common stock prices. Journal of Financial Economics, 17(1), 57–89.

Hosmer, D., Lemeshow, S., & Sturdivant, R. (2013). Applied logistic regression (3rd ed.). Hoboken: Wiley.

Keoun, B., & Henry, D. (2010). Bank profits depend on debt-writedown “abomination” in forecast. Bloomberg Business. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2010-07-11/bank-earnings-depending-on-debt-writedown-abomination-in-latest-forecast. Accessed December 21, 2017.

Kohlbeck, M. (2004). Investor valuations and measuring bank intangible assets. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 19(1), 29–60.

Leone, A., Minutti-Meza, M., & Wasley, C. (2017). Influential observations and inference in accounting research. Working paper. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2407967. Accessed 2017 Sept.

Merton, R. (1974). On the pricing of corporate debt: The risk structure of interest rates. The Journal of Finance, 29(2), 449–470.

Nissim, D., & Penman, S. (2007). Fair value accounting in the banking industry. Working paper. Columbia Business School. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7916/D89310ZS.

Petersen, M. (2009). Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. The Review of Financial Studies, 22(1), 435–480.

Pinches, G., & Singleton, J. (1978). The adjustment of stock prices to bond rating changes. The Journal of Finance, 33(1), 29–44.

Acknowledgements

This paper has benefited from comments of workshop participants at the University of Waterloo, Central University of Finance and Economics, Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, University of Texas at Austin, Georgia State University, Tsinghua University, NYU Pollack Center for Law & Business Corporate Governance Luncheon, American Accounting Association Annual Meeting, Canadian Academic Accounting Association Annual Conference, and Transatlantic Doctoral Conference at London Business School. We particularly thank Stephen Ryan, Patricia O’Brien, Christine Wiedman, Sati Bandyopadhyay, and the anonymous referee, for their insightful comments. We are grateful for the funding provided by Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and CPA/Laurier Centre for the Advancement of Accounting Research and Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

-

1.

An example of DVA loss disclosure in FR Y-9C report filed with the Federal Reserve. Excerpted from Citigroup’s filing as of December 31, 2010 (page 4).

-

2.

An example of DVA loss disclosure in 10-K form filed with SEC. Excerpted from Citigroup’s filing as of December 31, 2010 (page 272)

1.1 Own credit valuation adjustment

The fair value of debt liabilities for which the fair value option is elected (other than nonrecourse and similar liabilities) is impacted by the narrowing or widening of the Company’s credit spreads. The estimated change in the fair value of these debt liabilities due to such changes in the Company’s own credit risk (or instrument-specific credit risk) was a loss of $589 million and $4.226 billion for the years ended December 31, 2010 and 2009, respectively. Changes in fair value resulting from changes in instrument-specific credit risk were estimated by incorporating the Company’s current observable credit spreads into the relevant valuation technique used to value each liability as described above.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cedergren, M.C., Chen, C. & Chen, K. The implication of unrecognized asset value on the relation between market valuation and debt valuation adjustment. Rev Account Stud 24, 426–455 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-019-9486-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-019-9486-2

Keywords

- Debt valuation adjustment

- Unrecognized asset value

- Market valuation

- Fair value of liabilities

- Balance sheet incompleteness