Abstract

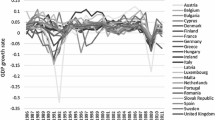

We build a weighted network of business cycle similarities across countries and assess its main quantitative properties. Business cycle similarity is measured at the annual frequency using the Euclidean distance. Network analysis is well suited to map the full set of pairwise similarities at an annual frequency. We find that the global business cycle network has become more dense and more homogeneous over time, reflecting global trends such as rising trade and financial integration. At the same time, similarity exhibits a jagged pattern, underscoring the importance of also taking into account short-term factors to explain the dynamics of global business cycle interdependence. Unlike earlier studies focused on aggregate measures of similarity, our empirical approach is able to uncover and assess both the long-term trend rise and the short-term pattern of business cycle similarity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The terminology varies across the literature, e.g. business cycle synchronisation, correlation, comovement, interdependence, association, or similarity. All these words are interchangeable insofar as they allow for similar business cycle dynamics to emerge either from common shocks, or from country-specific shocks spilling across national borders. In this paper, we adopt the terminology of business cycle similarity in line with the standard jargon of network analysis.

We also estimated the trend component using the Baxter-King filter as a robustness check. The resulting output gaps are very similar.

The full list of countries is available in Table 1 in the Appendix.

Some other studies have used monthly data on industrial production or the rate of unemployment as measures of the business cycle. The former is inadequate as the share of industry in the economy has been shrinking in many countries to a relatively low level. Thus, the evolution of industrial production is not representative of the dynamics of an economy as a whole. The latter is also inadequate as the rate of unemployment is known to be a lagging indicator of economic activity.

For example, Artis and Zhang (1997, 1999) have concluded that participation in the Exchange Rate Mechanism of mutually fixed exchange rates raised business cycle similarity, while Inklaar and De Haan (2001) reached the opposite conclusion using the same dataset but splitting in different sub-samples.

Mink et al. (2012) propose a comparable measure based on the idea of distance.

There is a functional correspondence between the correlation coefficient and the Euclidean distance when two time series are standardised (zero mean and unit variance). In this case, the correlation coefficient and the Euclidean distance provide the same qualitative information about similarity. See Waelti (2012) for further details.

We use the igraph package within the R statistical software to build network graphs and compute some of the quantitative characteristics of the network.

Most of the studies mentioned in the previous section build networks where the business cycles of two countries are either connected or they are not. Said differently, two countries in the network are linked by a straight line only if the similarity between them exceeds an arbitrary threshold. This binary approach is inefficient since it discards useful information contained in continuous measures of similarity.

We use the full sample of countries to assess the properties of the network in the next section.

We experimented with alternative bins. The thrust of our results remains unchanged.

We constructed an alternative network for each year using such a binary concordance index. These charts are available from the authors upon request.

References

Aguiar M, Gopinath G (2007) Emerging market business cycles: the cycle is the trend. J Polit Econ 115(1):69–102

Antonakakis N, Gogas P, Papadimitriou T, Sarantitis GA (2016) International business cycle synchronization since the 1870s: evidence from a novel network approach. Phys A: Stat Mech Appl 447:286–296

Artis MJ, Zhang W (1997) International business cycles and the ERM: is there a European business cycle? Int J Finance Econ 2(1):1–16

Artis MJ, Zhang W (1999) Further evidence on the international business cycle and the ERM: is there a European business cycle? Oxford Econ Pap 51 (1):120–132

Barrat A, Barthelemy M, Pastor-Satorras R, Vespignani A (2004) The architecture of complex weighted networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101 (11):3747–3752

Baxter M, Kouparitsas MA (2005) Determinants of business cycle comovement: a robust analysis. J Monet Econ 52(1):113–157

Caraiani P (2013) Using complex networks to characterize international business cycles. PloS One 8(3):e58109

Cerqueira PA (2011) How pervasive is the world business cycle? Open Econ Rev 22:119–142

Darvas Z, Szapary G (2008) Business cycle synchronisation in the enlarged eu. Open Econ Rev 19:1–19

Dées S, Zorell N (2012) Business cycle synchronisation: disentangling trade and financial linkages. Open Econ Rev 23:623–643

Ductor L, Leiva-Leon D (2016) Dynamics of global business cycle interdependence. J Int Econ 102:110–127

Forbes K, Rigobon R (2002) No contagion, only interdependence: measuring stock market comovements. J Finance 57(5):2223–2261

Frankel JA, Rose AK (1998) The endogenity of the optimum currency area criteria. Econ J 108(449):1009–1025

Gomez DM, Ferrari HJ, Torgler B, Ortega GJ, et al. (2017) Synchronization and diversity in business cycles: a network analysis of the European Union. Appl Econ 49(10):972–986

Imbs J (2004) Trade, finance, specialization, and synchronization. Rev Econ Stat 86(3):723–734

Imbs J (2010) The first global recession in decades. IMF Econ Rev 58(2):327–354

Inklaar R, De Haan J (2001) Is there really a European business cycle? A comment. Oxford Econ Pap 53(2):215–220

Mink M, Jacobs JP, de Haan J (2012) Measuring coherence of output gaps with an application to the euro area. Oxford Econ Pap 64(2):217–236

Otto G, Voss GM, Willard L (2001) Understanding OECD output correlations. Research Paper 2001-05, Reserve Bank of Australia

Papadimitriou T, Gogas P, Sarantitis GA (2016) Convergence of European business cycles: a complex networks approach. Comput Econ 47(2):97–119

Snijders T (1981) The degree variance: an index of graph heterogeneity. Social Netw 3(3):163–174

Waelti S (2012) The myth of decoupling. Appl Econ 44 (26):3407–3419

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Swiss National Bank. Most of the work on this paper was carried out while Amalia Repele was at the Swiss National Bank. We thank the Editor, two anonymous referees, and colleagues at the Swiss National Bank for perceptive comments and suggestions.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Repele, A., Waelti, S. Map** the Global Business Cycle Network. Open Econ Rev 32, 739–760 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-020-09615-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-020-09615-1