Abstract

Positive parenting and appropriate interaction with children are globally recognized as pivotal in enhancing children’s quality of life. Evaluating family intervention programs is therefore vital, particularly in regions that lack reliable tools for assessment. This manuscript details a study conducted in Ecuador, a country noted for its scarcity of validated instruments to assess the impact of such interventions, especially for vulnerable preschool children. We focused on the application of the North Carolina Family Assessment Scale (NCFAS), a well-established measure to evaluate family functioning internationally, to Ecuadorian families with preschool children who are deemed vulnerable. The Spanish translation of the original scale was administered by trained evaluators to 470 preschool children in Machala, Ecuador. Our examination of the psychometric properties of the NCFAS in this context demonstrated high internal consistency. Additionally, factor analysis corroborated the reliability and validity of this adapted version of the NCFAS, albeit with a reduced item count. This research supports the effectiveness of the NCFAS in the Ecuadorian setting and underscores its potential utility in further studies involving varied demographic groups within the country. The results of this study have substantial implications for the enhancement of children’s quality of life in Ecuador through family intervention programs.

Highlights

-

The Ecuadorian study used the NCFAS to assess 470 vulnerable preschoolers’ environments.

-

High internal consistency and reliability were confirmed in this context.

-

The adapted version with fewer items was validated through factor analysis.

-

The results are pivotal for designing interventions in areas lacking reliable tools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Social programs are essential tools for governments that aim to mitigate the effects of socioeconomic disadvantage, vulnerability, morbidity, and mortality (Bernal-Salazar & Rico, 2010; Shahidi et al., 2019). Researching and evaluating these programs enhances their effectiveness, further benefiting public management (Haefner, 2011; Rossi et al., 2018).

Vulnerability is often characterized by limited economic income, unstable employment, lower education levels, challenges in accessing basic services, inadequate housing, and difficulty in navigating adverse situations. These conditions frequently result in environments marked by violence and family conflict that often have the greatest impact on women and children (Busso, 2001; Ortiz-Ruiz & Díaz-Grajales, 2018). This is a pervasive issue in Latin America (Giacometti & Pautassi, 2014). In Ecuador, for instance, there are alarming statistics regarding child violence; for instance, 47% of afro-descendant parents use physical discipline on their children. Although this trend appears to be declining among the mestizo/white and indigenous populations, it remains a concern (Yumbay, 2019).

To promote children’s well-being and prevent abuse, early intervention and support for vulnerable families that emphasize positive parenting are crucial (Fernandez, 2007). Such programs must be evidence-based, and their designs and evaluations must be firmly grounded in previous research. A significant challenge in non-English-speaking countries arises when psychological tools developed in different cultural contexts are employed without proper adaptation or without understanding of their psychometric properties (Matus et al., 2008). This situation complicates the assessment of programs that target childhood and family functioning (Valencia & Gómez, 2010).

Several instruments assess family functioning. Some instruments primarily highlight problems or dysfunctional family attributes, while others focus on family strengths, balancing the consideration of challenges with resources and resilience (Early & GlenMaye, 2000). Johnson et al. (2008) conducted an exhaustive review of 85 family assessment instruments related to children’s well-being. They identified seven scales that were particularly promising: the North Carolina Family Assessment Scale (NCFAS), the North Carolina Family Assessment Scale for Reunification (NCFAS-R), Strengths and Stressors Tracking Device (SSTD), Family Assessment Form (FAF), Family Assessment Checklist (FAC), Ackerman-Schoendorf Scales for Parent Evaluation of Custody (ASPECT), and Darlington Family Assessment System (DFAS). Among these, the NCFAS emerged as the most validated scale for assessing children’s well-being and demonstrated excellent suitability for evaluations in such contexts.

The NCFAS emerges as a pivotal scale for assessing family functioning that emphasizes the identification of family strengths and extensive utilization within vulnerable populations. It facilitates in-depth analyses of improvements in family intervention processes, sustained monitoring of user progress, and comprehensive assessment of program efficacy (Johnson et al., 2008). In 1991, following the approval of the Intensive Family Preservation Services (IFPS) program by North Carolina legislation, the NCFAS was developed as part of a state contract. The original authors were assigned to develop an evaluative tool aimed at identifying alterations in family functioning induced by the program. The scale was intended to be ecologically oriented and to align with the primary objective of the IFPS program of preventing unnecessary removal of children from their homes and inducing transformation while maintaining family unity (Kirk & Reed-Ashcraft, 2004). Over the years, several versions of the NCFAS have been introduced: the NCFAS-R for reunification, the NCFAS-G for general services, and the NCFAS G + R, which blends elements from the NCFAS-G and the NCFAS-R. Each version of the scale is distinctly formulated with respect to its intended objective (Kirk, 2012).

These versions of the NCFAS serve as potent tools for a holistic assessment of family well-being. Initially conceived with child welfare issues in mind, the applicability of these scales have been broadened to families that do not necessarily interface with child protection agencies (Kirk, 2012). Several studies, including those by Reed (1998), Reed-Ashcraft et al. (2001), Kirk et al. (2005), Kirk and Martens (2006), Kirk et al. (2007), Valencia and Gómez (2010) and Kirk and Martens (2015), have affirmed the psychometric integrity of the NCFAS across its various iterations. Supported by evidence of its internal consistency and validity, the original NCFAS and its subsequent versions have been a staple in myriad studies, as delineated in Table 1. Examples of these studies include works by Fernandez (2007), Farrell et al. (2010), Gómez et al. (2010), Hurley et al. (2011), Conner and Fraser (2011), and Olsen et al. (2015).

Lee and Lindsey (2010) investigated the measurement properties of the NCFAS within the realm of youth mental health services. They found that the NCFAS did not operate identically between child mental health contexts and child welfare frameworks. This pivotal revelation underscores the necessity of tailoring the NCFAS when deploying it for specific cohorts, such as vulnerable preschool-aged children, to ensure its potency and pertinence.

An agreement between the National Family Preservation Network (NFPN) and the Child Protector of Chile facilitated the translation of the NCFAS into Spanish. The Spanish rendition was developed using expert evaluations from both the NFPN and the Faculty of Education and Family Sciences of the Finis Terrae University of Chile. The translated version encompasses five components: scale and definitions; frequently asked questions; goal establishment; case studies; and a PowerPoint presentation for training purposes. The Spanish iteration of the NCFAS exhibited sound psychometric properties when applied to the Chilean populace. The Chilean exploration centered on children and adolescents who averaged 9.4 years of age (SD = 4.2) and were enrolled in programs that catered to families with high-risk indicators for child maltreatment (Valencia & Gómez, 2010).

The NCFAS has been extensively used in contexts characterized by elevated risks with the aim of preventing family disintegration. In Ecuador, the most culturally proximate environment where the scale received validation was Chile. Researchers investigated the psychometric properties of the scale congruent with the original objectives of its creation with a focus on high-risk children. We propose that in Ecuador, the NCFAS might be suitable for preschoolers who are vulnerable due to their social circumstances, even if they are not explicitly recognized as high-risk or incorporated into the protection system. The Ecuadorian cohort differs from the Chilean cohort both demographically and in its unique characteristics. Hence, we address two pivotal questions: (1) What is the factorial structure of the NCFAS for Ecuadorian families with vulnerable preschoolers? and (2) How internally consistent is the NCFAS for this sample?

Methods

Participants

Recruitment and Eligibility

We recruited participants for this study through 14 Child Development Center (CDC) coordinators who held degrees in various fields of psychology, including clinical, educational, and child psychology. At the onset of the study, these professionals were already acquainted with the children and had been familiar with their family environments for a minimum of seven months.

The inclusion criteria required the children to belong to vulnerable populations with families that were unable to provide adequate care due to circumstances such as poverty, extreme poverty, unemployment, suboptimal income levels, insufficient parental capabilities, reduced cultural acuity, and/or a lack of educational attainment. We determined eligibility by analyzing the vulnerability forms completed by each family.

Sample Characteristics

A total of 470 children met the inclusion criteria. Table 2 presents the descriptive characteristics of the participants. Due to the constraints of the COVID-19 pandemic, we were able to obtain socioeconomic information for only 413 of the 470 children. From the collected data, 29% of the children reported experiencing insufficient food availability in recent weeks, and 82% of the parents were employed, although 50% were employed in temporary capacities. Of the children’s mothers, 62% were employed, with only 22% in permanent positions. A substantial 99% of children resided with their biological mothers; however, 33% did not live with both biological parents. It was reported that 15% resided in households where domestic violence was prevalent.

Procedure

We obtained authorization to use the scale by contacting the NFPN, which supplied us with the original Spanish-translated scale package. Subsequently, the Ministry of Economic and Social Inclusion granted approval for the implementation of the NCFAS at the 14 CDCs in Machala, Ecuador. To ensure adherence to the NCFAS, we conducted training using the package supplied by the NFPN involving professionals across all 14 CDCs. Although these professionals developed their assessment skills independently, our team collaborated on completing each NCFAS form to enhance the rigor of the process. We recruited an external evaluator skilled in conducting psychological interviews to enable collaboration with the principal researcher in overseeing, monitoring, and controlling the completion of the NCFAS forms.

We created a Google Forms document to optimize data collection by facilitating online registration and transitioning from paper and pencil to a digital instrument. After obtaining informed consent from the children’s representative and the coordinator, we began the information collection process with scheduled visits to each CDC.

Each analysis took approximately 30 min per child. During this time, professionals answered the questions of the scale, relying on their knowledge acquired through daily interactions and care processes and referring to individual file information. This file contained (a) a record of individuals receiving care at the center, (b) a vulnerability sheet, (c) a general data sheet, (d) a child care sheet, (e) a child nutritional status monitoring sheet, and (f) a comprehensive child development indicators sheet. From July 2019 to February 2020, we meticulously executed data collection. The data were coded to maintain confidentiality and preserve the anonymity of the digital records of cases.

Measurement

We used the original version of the NCFAS, which was translated into Spanish by the NFPN. It features 5 global and 31 specific items as presented in Table 3 (Kirk & Reed-Ashcraft, 2007). This scale is designed to assess difficulties and strengths, with scoring occurring at the commencement and conclusion of the program. Initial ratings assist in develo** intervention plans and setting objectives, while final ratings assess changes after program application (Kirk & Reed-Ashcraft, 1998). The evaluation employs a scaling system ranging from -3 to +2, with each value corresponding to a distinct level of family functioning. A score of -3 indicates a “severe problem”, showing deteriorating family dynamics. A score of +2 represents a “clear strength” or an optimum level of familial functioning. A score of 0 serves as the baseline, representing an “adequate” level of functioning and suggesting no immediate need for intervention from protective services, although it does not signify the absence of familial challenges. A guideline is provided to aid professionals in the scoring process. For intermediate values such as +1, “minor strength,” and -1 and -2, representing “minor problem” and “moderate problem,” there are no fixed criteria; therefore, professionals use their judgment and expertize to assign these scores (Kirk & Reed-Ashcraft, 2007).

Kirk and Reed-Ashcraft (2004) found that certain items are not applicable in specific family structures. For instance, when children are not of school age or lack siblings, evaluation is not feasible, and the item is marked NA (not applicable).

Data Analysis

We analyzed descriptive statistics and internal consistency using the Python program (Python, 2022). We ascertained validity through data processing with Jamovi version 2.2 computer software (Jamovi, 2021). The data management necessitated the conversion of rating values from +2 (clear strength) to -3 (serious problem) into positive values ranging from 1 (clear strength) to 6 (serious problem).

We conducted an initial descriptive analysis to ascertain the distribution of the items. In this analysis, we focused on global items, which are equivalent to specific items, and used methodologies similar to those in preceding studies of the same scale. The principal descriptive statistics encompassed the mean, mode, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis. We processed the data associated with the child well-being factor using a method that handles listwise deletion, incorporating the items “school performance” and “relationship with sibling(s)” This approach was essential because 233 out of the 470 children were only children, and some were not of age for academic performance measurement.

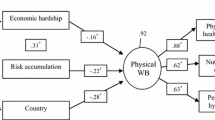

To validate the Ecuadorian iteration of the NCFAS, we employed both confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and exploratory factor analysis (EFA). For these analyses, global weighting items were omitted because their outcomes are contingent on the ratings of other items. We first executed CFA on the complete sample (n = 470) to confirm the coherence in the item distribution based on the original NCFAS. Following this, cross-validation was instituted by partitioning the study group into two distinct, nonoverlap** subsamples (n1 = 235, n2 = 235). The first subsample underwent a sequence of EFAs with oblique rotation, a method that is suitable for correlated and uncorrelated factors and yields accessible interpretation (Osborne, 2015). Finally, we applied CFA on the alternate subsample (n2 = 235) to confirm coherence in item distribution in alignment with the EFA outcomes and compared it with the reference values of the EFA adjustment indices: comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Indices indicative of optimal fit included CFI values of 0.95 or higher, RMSEA values of 0.05 or lower (Lai, 2021), TLI values greater than 0.90 (** stone to gain insight into the reliability and validity of the NCFAS in the unique context of Ecuador. The findings illuminate the need for further nuanced explorations and validations in varied settings to truly grasp the multifaceted implications and applications of the NCFAS.

Practical Implications

The proven psychometric reliability and validity of the NCFAS make it an integral part of various research and intervention programs (Akin & Gomi, 2017; Akin et al., 2018; Conner & Fraser, 2011; Taibo et al., 2018; Farrell et al., 2010; Fernandez, 2007, 2013a, 2013b; Fernandez & Atwool, 2013; Fernandez & Lee, 2011, 2013; Gómez, 2010; Gómez et al., 2012; Hurley et al., 2011; Katsikitis et al., 2013; Malvaso & Delfabbro, 2020; Meadowcroft et al., 2018; Pérez & Santelices, 2016; Yan & De Luca, 2021). By evaluating its psychometric properties and outlining a factorial structure suitable for preschoolers within vulnerable families in Ecuador, we enable the use of the NCFAS in child-centered programs in Ecuador. This allows for the quantification of the outcomes and transformations that families experience during interventions.

Likewise, we can use the scale as a pivotal tool in creating innovative programs aimed at preempting child maltreatment within familial contexts. Historically, there has been a lack of measures dedicated to exploring family dynamics among Ecuadorian preschoolers and evaluating the effectiveness of intervention schemes. The NCFAS fills this gap as a validated, reliable, concise, and user-friendly tool that is essential for both researchers and practitioners in evaluating familial functions.

Limitations

We recognize the limitations of the current study. Our ability to generalize the findings is potentially constrained by the specific sample, especially in the context of the extensive research on NCFAS. Additionally, the unique characteristics of our sample, which was derived from the CDC of a single city in Ecuador, indicate that our results may not apply to vulnerable preschoolers in other cities or reflect the broader Ecuadorian populace. Despite these limitations, our study provides evidence of internal consistency and reliability within a three-factor model and offers empirical support for the use of the NCFAS in evaluating vulnerable preschoolers. This aids in identifying immediate family functioning issues that require intervention and promotes improvements in family functionality. Seeing this scale as the first instrument to assess family functioning with validated psychometric properties in Ecuador accelerates the evaluation of programmatic outcomes in terms of economic efficacy and societal benefit. Furthermore, it can form a basis for future studies exploring the psychometric properties of the NCFAS in other representative samples, covering various areas and demographic sectors in Ecuador, and including high-risk or nonvulnerable populations.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript. The data have been deposited in BD INTEGRADA database, https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1dCrJ4u75YuvotSCQjwqcR-YKHrTtwqxzN-2XdG2pBeQ/edit?usp=sharing. Requests for material should be made to the corresponding authors. The data held by the Ministry of Economic and Social Inclusion, supports our claims. For data access, provide rationale at: https://bit.ly/NCFAS-EC-2023.

Code Availability

Stored on Google Docs, access requires ministry authorization and privacy adherence.

References

Akin, B. A., & Gomi, S. (2017). Noncompletion of evidence-based parent training: An empirical examination among families of children in foster care. Journal of Social Service Research, 43(1), 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2016.1226229.

Akin, B. A., Lang, K., Yan, Y., & McDonald, T. P. (2018). Randomized trial of PMTO in foster care: 12-month child well-being, parenting, and caregiver functioning outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review, 95, 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.10.018.

Bernal-Salazar, R., & Rico, D. (2010). La importancia de los programas para la primera infancia en Colombia. Universidad de los Andes, Facultad de Economía, CEDE.

Busso, G. (20 y 21 de junio del 2001). Vulnerabilidad social: nociones e implicancias de políticas para Latinoamérica a inicios del siglo XXI. Seminario Internacional “Las diferentes expresiones de la vulnerabilidad Social en América Latina y el Caribe”, Santiago de Chile. CEPAL.

Carmines, E. G., & Zeller, R. A. (1979). Reliability and validity assessment. SAGE Publications.

Cho, G., Hwang, H., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2020). Cutoff criteria for overall model fit indexes in generalized structured component analysis. Journal of Marketing Analytics, 8(4), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41270-020-00089-1.

Conner, N. W., & Fraser, M. W. (2011). Preschool social–emotional skills training: A controlled pilot test of the making choices and strong families programs. Research on Social Work Practice, 21(6), 699–711. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731511408115.

Early, T. J., & GlenMaye, L. F. (2000). Valuing families: Social work practice with families from a strengths perspective. Social Work, 45(2), 118–130. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/45.2.118.

Farrell, A. F., Britner, P. A., Guzzardo, M., & Goodrich, S. (2010). Supportive housing for families in child welfare: Client characteristics and their outcomes at discharge. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(2), 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.06.012.

Fernandez, E. (2007). Supporting children and responding to their families: Capturing the evidence on family support. Children and Youth Services Review, 29(10), 1368–1394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.05.012.

Fernandez, E. (2013a). Assessment and intervention. In E. Fernandez (Ed.), Accomplishing permanency: Reunification pathways and outcomes for foster children (pp. 45–66). Springer Netherlands.

Fernandez, E. (2013b). Care patterns and outcomes of reunification. In E. Fernandez (Ed.), Accomplishing permanency: Reunification pathways and outcomes for foster children (pp. 79–86). Springer Netherlands.

Fernandez, E., & Atwool, N. (2013). Child protection and out of home care: Policy, practice, and research connections Australia and New Zealand. Psychosocial Intervention, 22(3), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.5093/in2013a21.

Fernandez, E., & Lee, J.-S. (2011). Returning children in care to their families: Factors associated with the speed of reunification. Child Indicators Research, 4(4), 749–765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-011-9121-7.

Fernandez, E., & Lee, J.-S. (2013). Accomplishing family reunification for children in care: An Australian study. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(9), 1374–1384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.05.006.

Giacometti, C., & Pautassi, L. C. (2014). Infancia y (des)protección social: Un análisis comparado en cinco países latinoamericanos. Naciones Unidas; CEPAL-UNICEF

Gómez, E. (2010). El desafío de evaluar familias desde un enfoque ecosistémico: Nuevos aportes a la confiabilidad y validez de las escalas NCFAS. In L. Lira (Ed.), Familia y diversidad (pp. 95–126). Fundación San José para la Adopción

Gómez, E., Cifuentes, B., & Ortún, C. (2012). Padres competentes, hijos protegidos: Evaluación de resultados del programa “viviendo en familia. Psychosocial Intervention, 21(3), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.5093/in2012a23.

Gómez, E. A., Cifuentes, B., & Ross, M. I. (2010). Previniendo el maltrato infantil: Descripción psicosocial de usuarios de programas de intervención breve en Chile. Universitas Psychologica, 9(3), 823–840. https://doi.org/10.11144/javeriana.upsy9-3.pmid.

Haefner, C. (2011). Fortalezas y debilidades del desarrollo regional y social: El caso de la región de los lagos. Revista MAD (2). https://doi.org/10.5354/0718-0527.2000.14858

Hurley, K. D., Griffith, A. K., Casey, K. J., Ingram, S., & Simpson, A. (2011). Behavioral and emotional outcomes of an in-home parent training intervention for young children. Journal of At-Risk. Issues, 16(2), 1–7.

INEC. (2010, October 1). Población y demografía. https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/censo-de-poblacion-y-vivienda/

Jamovi. (2021). The Jamovi Project (version 2.2) [computer software]. https://www.jamovi.org/

Johnson, M. A., Stone, S., Lou, C., Vu, C. M., Ling, J., Mizrahi, P., & Austin, M. J. (2008). Family assessment in child welfare services: Instrument comparisons. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 5(1-2), 57–90. https://doi.org/10.1300/j394v05n01_04.

Katsikitis, M., Bignell, K., Rooskov, N., Elms, L., & Davidson, G. R. (2013). The family strengthening program: Influences on parental mood, parental sense of competence and family functioning. Advances in Mental Health, 11(2), 143–151. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.2013.11.2.143.

Kirk, R. S. (2012). Development, intent, and use of the North Carolina family assessment scales, and their relation to reliability and validity of the scales. https://www.nfpn.org/media/8d86bb8bc37491c/ncfas_scale_development.pdf

Kirk, R. S., Griffith, D. P., & Martens, P. (2007). An examination of intensive family preservation services. https://www.nfpn.org/media/8d86bb4d3205bc1/ifrs-research.pdf

Kirk, R. S., Kim, M. M., & Griffith, D. P. (2005). Advances in the reliability and validity of the North Carolina family assessment scale. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 11(3–4), 157–176. https://doi.org/10.1300/j137v11n03_08.

Kirk, R. S., & Martens, P. (2006). Development and field testing of the North Carolina Family Assessment Scale for general services (NCFAS-G). https://www.nfpn.org/media/8d86bbcfea93b33/ncfasg_research_report.pdf

Kirk, R. S., & Martens, P. (2015). Field test and reliability analyses of trauma and post-trauma well-being domains of the North Carolina Family Assessment Scale for general and reunification services. https://www.nfpn.org/media/8d86b1d66c9613b/trauma-report.pdf

Kirk, R. S., & Reed-Ashcraft, K. (2007). Escala de evaluación familiar de carolina del norte - escala & definiciones (Version 2). National Family Preservation Network.

Kirk, R. S., & Reed-Ashcraft, K. B. (1998). User’s guide for the North Carolina Family Assessment Scale (NCFAS) version 2.0. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.493.5929

Kirk, R. S., & Reed-Ashcraft, K. B. (2004). NCFAS research report. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.493.5929

Lai, K. (2021). Fit difference between nonnested models given categorical data: Measures and estimation. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 28(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2020.1763802.

Lee, B. R., & Lindsey, M. A. (2010). North Carolina family assessment scale: Measurement properties for youth mental health services. Research on Social Work Practice, 20(2), 202–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731509334180.

Malvaso, C. G., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2020). Description and evaluation of a trial program aimed at reunifying adolescents in statutory long-term out-of-home care with their birth families: The adolescent reunification program. Children and Youth Services Review, 119, 105570 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105570.

Matus, T., Haz, A. M., Razeto, A., Funk, R., Roa, K., & Canales, L. (2008). Innovar en calidad: Construcción de un modelo de certificación de calidad para programas sociales. Andros Impresores.

Mavrou, I. (2015). Análisis factorial exploratorio: Cuestiones conceptuales y metodológicas. Revista Nebrija de Lingüística Aplicada a la Enseñanza de Lenguas, 19, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.26378/rnlael019283.

Meadowcroft, P., Townsend, M. Z., & Maxwell, A. (2018). A sustainable alternative to the gold standard EBP: Validating existing programs. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 45(3), 421–439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-018-9599-6.

Ministerio de Turismo. (2008). Transportes en Ecuador. https://vivecuador.com/html2/esp/transporte.htm#:~:text=El%20servicio%20de%20taxi%20funciona%20eficazmente%20las%2024%20horas.&text=El%20bus%20es%20el%20medio,la%20distancia%20y%20al%20servicio.

Olsen, L. J., Laprade, V., & Holmes, W. M. (2015). Supports for families affected by substance abuse. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 9(5), 551–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2015.1091761.

Ortiz-Ruiz, N., & Díaz-Grajales, C. (2018). Una mirada a la vulnerabilidad social desde las familias. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 80(3), 611–638. https://doi.org/10.22201/iis.01882503p.2018.3.57739.

Osborne, J. W. (2015). What is rotating in exploratory factor analysis? Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 20, 2 https://doi.org/10.7275/hb2g-m060.

Oviedo, H. C., & Arias, A. C. (2005). Aproximación al uso del coeficiente alfa de Cronbach. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, XXXIV(4), 572–580.

Pérez, F., & Santelices, A. M. P. (2016). Sintomatología depresiva, estrés parental y funcionamiento familiar. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, XXV(3), 235–244.

Python. (2022). Python software foundation (version 3) [computer software]. http://www.python.org

Reed-Ashcraft, K., Kirk, R. S., & Fraser, M. W. (2001). The reliability and validity of the North Carolina Family Assessment Scale. Research on Social Work Practice, 11(4), 503–520. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973150101100406.

Reed, K. (1998). The reliability and validity of the North Carolina Family Assessment Scale. University of North Carolina.

Rossi, P. H., Lipsey, M. W., & Henry, G. T. (2018). Evaluation: A systematic approach. SAGE Publications.

Shahidi, F. V., Ramraj, C., Sod-Erdene, O., Hildebrand, V., & Siddiqi, A. (2019). The impact of social assistance programs on population health: A systematic review of research in high-income countries. BMC public health, 19(1), 2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6337-1.

Taibo, L. C., Gutierrez, C. P., & Muzzio, E. G. (2018). Graves vulneraciones de derechos en la infancia y adolescencia: Variables de funcionamiento familiar. Universitas Psychologica, 17(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.11144/javeriana.upsy17-3.gvdi.

Valencia, E., & Gómez, E. (2010). An eco-systemic family assessment scale for social programs: Reliability and validity of NCFAS in a high psychosocial risk population. Psykhe (Santiago), 19(1), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-22282010000100007.

Worthington, R. L., & Whittaker, T. A. (2006). Scale development research: A content analysis and recommendations for best practices. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(6), 806–838. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006288127.

**a, Y., & Yang, Y. (2019). RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behavior Research Methods, 51(1), 409–428. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1055-2.

Yan, Y., & De Luca, S. (2021). Heterogeneity of treatment effects of PMTO in foster care: A latent profile transition analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01798-y.

Yumbay, M. (26 de febrero del 2019). Proyecto de Red de Protección Social en Ecuador. Ministerio de Inclusión Económica Y Social. https://www.inclusion.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/2PRIM.pdf.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.R.-M. collected information and articulated the research narrative. M.S. co-wrote, revised, and refined content. I.R.-M. managed statistics, ensuring accurate analysis. All authors endorsed the manuscript and vouch for its accuracy.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All protocols with human participants were executed in compliance with the Ethics and Biosafety Committee of the University of Girona. This committee endorsed the project “Development of Positive Parenting via a Virtual Reality and Video Intervention Program—Project Code: CEBRU0033-21,” which includes research on “Psychometric Properties of NCFAS in Vulnerable Ecuadorian Populations.”

Informed consent

We uphold ethical standards, ensuring rights protection for all participants. Each provided informed consent, with any identifiable information either anonymized or included for academic purposes with clear consent. We have permissions to publish anonymized data and adhere to the guidelines of the University of Girona and the Journal of Child and Family Studies.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramírez-Morales, K., Sadurní, M. & Ramirez-Morales, I. Psychometric Properties of the North Carolina Family Assessment Scale (NCFAS) for Vulnerable Preschoolers from Ecuador. J Child Fam Stud 33, 103–113 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-023-02709-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-023-02709-7