Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic can have a serious impact on children and adolescents’ mental health. We focused on studies exploring its traumatic effects on young people in the first 18 months after that the pandemic was declared, distinguishing them also according to the type of informants (self-report and other-report instruments).

Objective

We applied a meta-analytic approach to examine the prevalence of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic, considering the moderating role of kind of disorder and/or symptom, type of instrument, and continent.

Method

We used PsycINFO, PubMed, and Scopus databases to identify articles on the COVID-19 pandemic, applying the following filters: participants until 20 years of age, peer-review, English as publication language. Inclusion required investigating the occurrence of disorders and/or symptoms during the first 18 months of the pandemic. The search identified 26 publications.

Results

The meta-analysis revealed that the pooled prevalence of psychological disorders and/or symptoms for children and adolescents, who were not affected by mental health disturbances before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, was .20, 95% CI [.16, .23]. Moreover, we found a moderating role of type of instrument: occurrence was higher for self-report compared to other-report instruments.

Conclusions

The study presented an analysis of the psychological consequences for children and adolescents of the exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic, soliciting further research to identify factors underlying resilience. Notwithstanding limitations such as the small number of eligible articles and the fact that we did not examine the role of further characteristics of the studies (such as participants’ age or design), this meta-analysis is a first step for future research documenting the impact of such an unexpected and devastating disaster like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is a biological natural disaster with a serious impact on both physical and mental health (EM-DAT, 2022; Jones et al., 2021). As many other disasters, pandemics can cause great suffering at the physical, biological, and social level, with dangerous consequences for individuals’ health and wellbeing (World Health Organization, 2022). Generally, children and adolescents exposed to a disaster are considered to be at risk, because of their heightened vulnerability. For this reason, they need special attention compared to adults during emergencies (Peek et al., 2018).

Disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic have cascading and cumulative effects that pose many challenges to young people and their families (Masten & Motti-Stefanidi, 2020). In terms of mental health, among the traumatic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic there can be an increase of psychological disorders and/or symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and sleep disorders in children and adolescents (Golberstein et al., 2020). The knowledge on their prevalence is paramount to develop and implement evidence-informed interventions to cope with the traumatic consequences of the pandemic and to foster their resilience, both during and after its occurrence. Therefore, we examined the literature on psychological disorders and/or symptoms, assessed through self-report or other-report instruments, in children and adolescents; we took into account studies published in the first 18 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, using a meta-analytical approach.

Impact of COVID-19 on Children and Adolescents

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (2022) declared that the spreading of the COVID-19 was a global pandemic. Many countries claimed a state of emergency, implementing strict public health measures. The safety measures taken, such as school closures, social distance, and indications on health protection behaviors, have had a strong impact on global mental health for children and adolescents (Ellis et al., 2020; Holmes et al., 2020). Recent literature confirmed that they are particularly exposed to the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic from a psychological perspective (Cost et al., 2021; Kılınçel et al., 2020; Lavigne-Cerván et al., 2021; Ravens‑Sieberer et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2021, 2022b; Vicentini et al., 2020).

Method

Literature Search and Search Results

We conducted systematic searches in three databases during September 2021: PsycINFO, PubMed, and Scopus. We decided to focus on PsycINFO and PubMed as they are among the most authoritative databases for conducting meta-analyses in mental health research (Cuijpers, 2016). In addition, following guidelines suggesting not to confine reviews to one or two databases (Cheung & Vijayakumar, 2016; Lemeshow et al., 2005), we decided to examine also a citation database like Scopus to find other relevant articles, in line with previous experiences (e.g., Filatova et al., 2017; Hendriks et al., 2018). We used the following search terms: “COVID-19” AND “children and adolescents” AND “mental health”. Concerning inclusion criteria, we considered studies which: (a) involved participants until 20 years of age; (b) included the assessment of at least one measure of psychological disorders and/or symptoms; (d) reported the occurrence of disorders and/or symptoms so that effect sizes (ES) could be calculated; (e) analyzed data that were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic; (f) were written in English. We excluded publications reporting reviews, discussions, single-case studies, and qualitative studies. Moreover, we excluded those studies whose participants suffered from physical or mental illness prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and those studies which did not include the statistical indexes necessary as inputs for a meta-analysis.

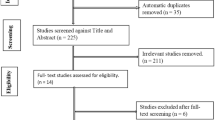

The initial search identified a total of 1163 works published between the outbreak of the pandemic and September 30, 2021. Four-hundred and thirty-eight publications were indexed in PsycINFO, 448 were indexed in PubMed, and 277 were indexed in Scopus. As a first step, we removed 432 duplicates from this initial set, i.e., the same publications downloaded in different searches. Then, we screened the 731 selected publications. As a second step, we read all the titles and abstracts and included only the publications pertinent in terms of topic—i.e., respecting the inclusion criteria—for a total of 83. As a third step, we read each article, and this led us to exclude 36 publications because they were off topic, and 21 because they reported reviews, discussions, single-case studies, and qualitative studies. This last step of the selection process was conducted by two independent judges; the reliability was 100%. No publications were excluded after the discussion between judges. Thus, the search identified a selection of 26 publications. We report in the PRISMA diagram (Fig. 1) the results of the selection process (Moher et al., 2009).

PRISMA diagram (Moher et al., 2009)

For ethical issues, we adhered to the recommendations of the American Psychological Association.

Coding and Reliability

We reviewed and coded the eligible studies for several variables. We coded measures of psychological disorders and/or symptoms, in terms of occurrence of depression, anxiety, PTSD, and psychological distress. We also coded the type of instrument (distinguishing self-report and other-report instruments) and the continent (North America, Asia, and Europe). The moderating effect of age was not examined, because in most studies children and adolescents were not separated. For an overview of the included studies, see Table 1.

Measures

Several authors explored the incidence of psychological disorders and/or symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents. We coded their occurrence, distinguishing them in four categories: depression (e.g., Cao et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2008).

Following the suggestion of Van den Noortgate and Onghena (2003), we used a two-step procedure. First, we ran a traditional random-effects meta-analysis: we evaluated the main effects, performed the influence analyses, and checked the publication bias. Second, we ran a multilevel mixed-effects meta-analysis to examine the role of the moderators. We checked whether the results of the traditional random-effects model differed from the results of the multilevel mixed-effects model, and we found that they were not substantially different.

For the multilevel mixed-effects models, we chose to use the restricted maximum-likelihood estimation method, because it seemed more appropriate for considering non-independent sampling errors due to the presence of multiple effects in the studies (Borenstein, 2009). We used Cochran’s heterogeneity statistic (Q) to test if the effect sizes of different studies were similar or not. A significant value of Q means that there is heterogeneity between the effect sizes. We used the I2 statistic to assess the level of heterogeneity. It measures the proportion of total variance due to the variability between the studies. We have low heterogeneity if the value of the statistic is between 1 and 49, medium if the value is between 50 and 74, and high if the value is between 75 and 100. We assessed the role of each moderator with mixed-effect models, considering the dependence of effect sizes through multilevel modelling (level 1 = effect sizes; level 2 = study). We conducted a test to evaluate the possible moderating effect of one or more variables included in the model. In this test, the null hypothesis was that all the regression coefficients were equal to zero, while the alternative hypothesis was that at least one of the regression coefficients was not equal to zero.

We examined the moderating role of the kind of disorder and/or symptom (depression, anxiety, PTSD, and psychological distress), the type of instrument used to assess disorders and/or symptoms (self-report and other-report), and the continent (North America, Asia, and Europe). We excluded those studies that did not have information on each moderator in the corresponding analysis. We assessed the potential publication biases using the trim and fill approach of Duval and Tweedie (2000). This approach estimates the number of studies missing from a meta-analysis by eliminating those studies that create patterns of asymmetry, and adding new data estimated on the initial sample to generate a symmetrical distribution of effect sizes. The output of this analysis is a funnel plot that is designed using the effect size against the standard error for each study.

Results

Prevalence of Psychological Symptoms and/or Disorders in Children and Adolescents

Initially, we analyzed the data concerning the proportions of children and adolescents affected by psychological disorders and/or symptoms reported in the studies included in the meta-analysis. Their incidence ranged from .07 to .67. Then, we transformed the proportions applying the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation and we ran a first random-effects model. This model, k = 47, n = 155.282, estimated a pooled incidence of psychological disorders and/or symptoms equal to .21, 95% CI [.17, .26], SE = .03. The effect sizes were heterogeneous, Q(46) = 22,862.65, p < .001, and the proportion of total variance due to the variability between the studies was very high, I2 = 99.76%.

Considering the forest plot, we identified two potential outlying effect sizes. We examined them further to determine whether they were really influential to the overall effect size. Following Viechtbauer and Cheung’s (2010) suggestions, we analyzed the outlying effect sizes (Chen et al., 2020a, 2020c). However, our results can be viewed focusing on the bright side of the medal: about 80% of the participants did not show the disorders and/or symptoms at issue. Future research should further explore the factors underlying the occurrence of mental health disturbances in certain cases and the absence of their development in many other cases. Such knowledge would be of primary relevance to implement actions to sustain children and adolescents’ resilience, also for possible future traumatic events.

References

*References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Assink, M., & Wibbelink, C. J. (2016). Fitting three-level meta-analytic models in R: A step-by-step tutorial. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 12(3), 154–174. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.12.3

Borenstein, M. (2009). Effect sizes for continuous data. In H. Cooper, L. V. Hedges, & J. C. Valentine (Eds.), Handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (2nd ed., pp. 221–235). Russell Sage Foundation.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2010). A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 1(2), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.12

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

*Cao, Y., Huang, L., Si, T., Wang, N. Q., Qu, M., & Zhang, X. Y. (2021). The role of only-child status in the psychological impact of COVID-19 on mental health of Chinese adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 282, 316–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.113

*Chen, X., Qi, H., Liu, R., Feng, Y., Li, W., **ang, M., Cheung, T., Jackson, T., Wang, G., & **ang, Y. T. (2021). Depression, anxiety and associated factors among Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak: A comparison of two cross-sectional studies. Translational Psychiatry, 11(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01271-4

Cheung, M. W. L., & Vijayakumar, R. (2016). A Guide to conducting a meta-analysis. Neuropsychology Review, 26, 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-016-9319-z

*Cost, K. T., Crosbie, J., Anagnostou, E., Birken, C. S., Charach, A., Monga, S., Kelley, E., Nicolson, R., Maguire, J. L., Burton, C. L., Schachar, R. J., Arnold, P. D., & Korczak, D. J. (2021). Mostly worse, occasionally better: Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01744-3

Courtney, D., Watson, P., Battaglia, M., Mulsant, B. H., & Szatmari, P. (2020). COVID-19 impacts on child and youth anxiety and depression: Challenges and opportunities. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie, 65(10), 688–691. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743720935646

Cuijpers, P. (2016). Meta-analyses in mental health research: A practical guide. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Dimitry, L. (2012). A systematic review on the mental health of children and adolescents in areas of armed conflict in the Middle East. Child: Care, Health and Development, 38(2), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01246.x

*Duan, L., Shao, X., Wang, Y., Huang, Y., Miao, J., Yang, X., & Zhu, G. (2020). An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in China during the outbreak of COVID-19. Journal of Affective Disorders, 275, 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029

Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x

*Ellis, W. E., Dumas, T. M., & Forbes, L. M. (2020). Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 52(3), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000215

EM-DAT. (2022). The international disaster database. Retrieved January 13, 2022, from https://emdat.be

Filatova, S., Koivumaa-Honkanen, H., Hirvonen, N., Freeman, A., Ivandic, I., Hurtig, T., Khandaker, G. M., Jones, P. B., Moilanen, K., & Miettunen, J. (2017). Early motor developmental milestones and schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research, 188, 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.01.029

Freeman, M. F., & Tukey, J. W. (1950). Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 21(4), 607–611. https://doi.org/10.1214/aoms/1177729756

Furr, J. M., Comer, J. S., Edmunds, J. M., & Kendall, P. C. (2010). Disasters and youth: A meta-analytic examination of posttraumatic stress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(6), 765–780. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021482

*Gladstone, T., Schwartz, J., Pössel, P., Richer, A. M., Buchholz, K. R., & Rintell, L. S. (2021). Depressive symptoms among adolescents: Testing vulnerability-stress and protective models in the context of COVID-19. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-021-01216-4

Golberstein, E., Wen, H., & Miller, B. F. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 819–820. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456

Grolnick, W. S., Schonfeld, D. J., Schreiber, M., Cohen, J., Cole, V., Jaycox, L., Lochman, J., Pfefferbaum, B., Ruggiero, K., Wells, K., Wong, M., & Zatzick, D. (2018). Improving adjustment and resilience in children following a disaster: Addressing research challenges. American Psychologist, 73(3), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000181

Hendriks, T., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Hassankhan, A., Graafsma, T., Bohlmeijer, E., & de Jong, J. (2018). The efficacy of positive psychology interventions from non-Western countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Wellbeing, 8(1), 71–98. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v8i1.711

Holmes, E. A., O’Connor, R. C., Perry, V. H., Tracey, I., Wessely, S., Arseneault, L., Ballard, C., Christensen, H., Cohen Silver, R., Everall, I., Ford, T., John, A., Kabir, T., King, K., Madan, I., Michie, S., Przybylski, A. K., Shafran, R., Sweeney, A., … Bullmore, E. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 547–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

*Hu, T., Wang, Y., Lin, L., & Tang, W. (2021). The mediating role of daytime sleepiness between problematic smartphone use and post-traumatic symptoms in COVID-19 home-refined adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review, 126, 106012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106012

*Islam, M. S., Ferdous, M. Z., & Potenza, M. N. (2020). Panic and generalized anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic among Bangladeshi people: An online pilot survey early in the outbreak. Journal of Affective Disorders, 276, 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.049

Jones, E., Mitra, A. K., & Bhuiyan, A. R. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in adolescents: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052470

*Kılınçel, Ş, Kılınçel, O., Muratdağı, G., Aydın, A., & Usta, M. B. (2020). Factors affecting the anxiety levels of adolescents in home-quarantine during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry: Official Journal of the Pacific Rim College of Psychiatrists, 13(2), e12406. https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12406

Lai, B. S., Auslander, B. A., Fitzpatrick, S. L., & Podkowirow, V. (2014). Disasters and depressive symptoms in children: A review. Child & Youth Care Forum, 43(4), 489–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-014-9249-y

*Lavigne-Cerván, R., Costa-López, B., Juárez-Ruiz de Mier, R., Real-Fernández, M., Sánchez-Muñoz de León, M., & Navarro-Soria, I. (2021). Consequences of COVID-19 confinement on anxiety, sleep and executive functions of children and adolescents in Spain. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 565516. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.565516

LeBreton, J. M., & Senter, J. L. (2008). Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organizational Research Methods, 11(4), 815–852. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106296642

Lemeshow, A. R., Blum, R. E., Berlin, J. A., Stoto, M. A., & Colditz, G. A. (2005). Searching one or two databases was insufficient for meta-analysis of observational studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 58(9), 867–873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.03.004

*Li, S. H., Beames, J. R., Newby, J. M., Maston, K., Christensen, H., & Werner-Seidler, A. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on the lives and mental health of Australian adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01790-x

*Liu, Q., Zhou, Y., **e, X., Xue, Q., Zhu, K., Wan, Z., Wu, H., Zhang, J., & Song, R. (2021a). The prevalence of behavioral problems among school-aged children in home quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Journal of Affective Disorders, 279, 412–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.008

*Liu, Y., Yue, S., Hu, X., Zhu, J., Wu, Z., Wang, J., & Wu, Y. (2021b). Associations between feelings/behaviors during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown and depression/anxiety after lockdown in a sample of Chinese children and adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 284, 98–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.001

Loades, M. E., Chatburn, E., Higson-Sweeney, N., Reynolds, S., Shafran, R., Brigden, A., Linney, C., McManus, M. N., Borwick, C., & Crawley, E. (2020). Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(11), 1218–1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

*Ma, Z., Idris, S., Zhang, Y., Zewen, L., Wali, A., Ji, Y., Pan, Q., & Baloch, Z. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic outbreak on education and mental health of Chinese children aged 7–15 years: An online survey. BMC Pediatrics, 21(1), 95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02550-1

*Mallik, C. I., & Radwan, R. B. (2021). Impact of lockdown due to COVID-19 pandemic in changes of prevalence of predictive psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents in Bangladesh. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 56, 102554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102554

Masten, A. S., & Motti-Stefanidi, F. (2020). Multisystem resilience for children and youth in disaster: Reflections in the context of COVID-19. Adversity and Resilience Science, 1(2), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-020-00010-w

Masten, A. S., & Osofsky, J. D. (2010). Disasters and their impact on child development: Introduction to the special section. Child Development, 81(4), 1029–1039. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01452.x

Miller, J. J. (1978). The inverse of the freeman—Tukey double arcsine transformation. The American Statistician, 32(4), 138. https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.1978.10479283

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Myers, K., & Winters, N. C. (2002). Ten-year review of rating scales. I: Overview of scale functioning, psychometric properties, and selection. American Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(2), 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200202000-00004

Panda, P. K., Gupta, J., Chowdhury, S. R., Kumar, R., Meena, A. K., Madaan, P., Sharawat, I. K., & Gulati, S. (2021). Psychological and behavioral impact of lockdown and quarantine measures for COVID-19 pandemic on children, adolescents and caregivers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 67(1), fmaa122. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmaa122

Pappa, S., Ntella, V., Giannakas, T., Giannakoulis, V. G., Papoutsi, E., & Katsaounou, P. (2020). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 88, 901–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026

Peek, L., Abramson, D. M., Cox, R. S., Fothergill, A., & Tobin, J. (2018). Children and disasters. In H. Rodríguez, W. Donner, & J. E. Trainor (Eds.), Handbook of disaster research (pp. 243–262). Springer.

Pekrun, R., & Bühner, M. (2014). Self-report measures of academic emotions. In R. Pekrun & L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 561–579). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Pfefferbaum, B., Weems, C. F., Scott, B. G., Nitiéma, P., Noffsinger, M. A., Pfefferbaum, R. L., Varma, V., & Chakraburtty, A. (2013). Research methods in child disaster studies: A review of studies generated by the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks; the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami; and hurricane Katrina. Child & Youth Care Forum, 42(4), 285–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-013-9211-4

Raccanello, D., Balbontín-Alvarado, R., Bezerra, D. d. S., Burro, R., Cheraghi, M., Dobrowolska, B., Fagbamigbe, A. F., Faris., M. E., França, T., González-Fernández, B., Hall, R., Inasius, F., Kar, S., K., Keržič, D., Lazányi, K., Lazăr, F., Machin-Mastromatteo, J. D., Marôco, J., Marques, B. P., Mejía-Rodríguez, O., et al. (2022a). Higher education students’ achievement emotions and their antecedents in e-learning amid COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country survey. Learning and Instruction, 80, 101629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101629

Raccanello, D., Barnaba, V., Rocca, E., Vicentini, G., Hall, R., & Burro, R. (2021). Adults’ expectations on children’s earthquake-related emotions and co** strategies. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 26(5), 571–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1800057

Raccanello, D., Rocca, E., Barnaba, V., Vicentini, G., Hall, R., & Brondino, M. (2022b). Co** strategies and psychological maladjustment/adjustment: A meta-analytic approach with children and adolescents exposed to natural disasters. Child & Youth Care Forum.. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-022-09677-x

Raccanello, D., Vicentini, G., Brondino, M., & Burro, R. (2020a). Technology-based trainings on emotions: A web application on earthquake-related emotional prevention with children. Advances in Intelligent and Soft Computing, 1007, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23990-9

Raccanello, D., Vicentini, G., & Burro, R. (2020b). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the academic and emotional life of higher education students in Italy. In N. Tomaževič & D. Ravšelj (Eds.), Higher education students and COVID-19: Consequences and policy implications (pp. 11–16). European Liberal Forum.

Raccanello, D., Vicentini, G., Rocca, E., Barnaba, V., Hall, R., & Burro, R. (2020c). Development and early implementation of a public communication campaign to help adults to support children and adolescents to cope with coronavirus-related emotions: A community case study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2184. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02184

R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. The R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved on February, 2020, from http://www.R-project.org/

Racine, N., McArthur, B. A., Cooke, J. E., Eirich, R., Zhu, J., & Madigan, S. (2021). Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(11), 1142–1150. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

*Ravens-Sieberer, U., Kaman, A., Erhart, M., Devine, J., Schlack, R., & Otto, C. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01726-5

Rubens, S. L., Felix, E. D., & Hambrick, E. P. (2018). A meta-analysis of the impact of natural disasters on internalizing and externalizing problems in youth. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(3), 332–341. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22292

Salehi, M., Amanat, M., Mohammadi, M., Salmanian, M., Rezaei, N., Saghazadeh, A., & Garakani, A. (2021). The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder related symptoms in Coronavirus outbreaks: A systematic-review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 282, 527–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.188

Sharma, M., Aggarwal, S., Madaan, P., Saini, L., & Bhutani, M. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on sleep in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine, 84, 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2021.06.002

*Shek, D., Zhao, L., Dou, D., Zhu, X., & **ao, C. (2021). The impact of positive youth development attributes on posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among Chinese adolescents under COVID-19. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 68(4), 676–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.01.011

*Tamarit, A., de la Barrera, U., Mónaco, E., Schoeps, K., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2020). Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in Spanish adolescents: Risk and protective factors of emotional symptoms. Revista de Psicologia Clinica con Ninos y Adolescentes, 7(3), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.21134/rpcna.2020.mon.2037

Tang, B., Liu, X., Liu, Y., Xue, C., & Zhang, L. (2014). A meta-analysis of risk factors for depression in adults and children after natural disasters. BMC Public Health, 14, 623. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-623

*Tang, S., **ang, M., Cheung, T., & **ang, Y. T. (2021). Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: The importance of parent-child discussion. Journal of Affective Disorders, 279, 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.016

Van den Noortgate, W., & Onghena, P. (2003). Multilevel meta-analysis: A comparison with traditional meta-analytical procedures. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63(5), 765–790. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164402251027

Vibhakar, V., Allen, L. R., Gee, B., & Meiser-Stedman, R. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of depression in children and adolescents after exposure to trauma. Journal of Affective Disorders, 255, 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.05.005

Vicentini, G., Brondino, M., Burro, R., & Raccanello, D. (2020). HEMOT®, Helmet for EMOTions: A web application for children on earthquake-related emotional prevention. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, 1241, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52538-5_2

Viechtbauer, W., & Cheung, M. W. (2010). Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 1(2), 112–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.11

*Walters, G. D., Runell, L., & Kremser, J. (2021). Social and psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on middle-school students: Attendance options and changes over time. School Psychology, 36(5), 277–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000438

Wang, N. (2018). How to conduct a meta-analysis of proportions in R: A comprehensive tutorial. Research Gate. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.27199.00161

Wang, C. W., Chan, C. L., & Ho, R. T. (2013). Prevalence and trajectory of psychopathology among child and adolescent survivors of disasters: A systematic review of epidemiological studies across 1987–2011. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(11), 1697–1720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0731-x

*Wang, L., Chen, L., Jia, F., Shi, X., Zhang, Y., Li, F., Hao, Y., Hou, Y., Deng, H., Zhang, J., Huang, L., **e, X., Fang, S., Xu, Q., Xu, L., Guan, H., Wang, W., Shen, J., Li, F., … Li, T. (2021a). Risk factors and prediction nomogram model for psychosocial and behavioural problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national multicentre study: Risk factors of childhood psychosocial problems. Journal of Affective Disorders, 294, 128–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.077

*Wang, J., Wang, H., Lin, H., Richards, M., Yang, S., Liang, H., Chen, X., & Fu, C. (2021b). Study problems and depressive symptoms in adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak: Poor parent-child relationship as a vulnerability. Globalization and Health, 17, 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00693-5

World Health Organization. (2022). Environmental health in emergencies. Natural events. Retrieved January 13, 2022, from https://www.who.int/environmental_health_emergencies/natural_events/en/#:~:text=Every%20year%20natural%20disasters%20kill,wildfires%2C%20heat%20waves%20and%20droughts

**e, X., Xue, Q., Zhou, Y., Zhu, K., Liu, Q., Zhang, J., & Song, R. (2020). Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei province, China. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 898–900. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1619

*Zhang, L., Zhang, D., Fang, J., Wan, Y., Tao, F., & Sun, Y. (2020). Assessment of mental health of Chinese primary school students before and after school closing and opening during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), e2021482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21482

*Zhou, J., Yuan, X., Qi, H., Liu, R., Li, Y., Huang, H., Chen, X., & Wang, G. (2020b). Prevalence of depression and its correlative factors among female adolescents in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00601-3

*Zhou, S. J., Zhang, L. G., Wang, L. L., Guo, Z. C., Wang, J. Q., Chen, J. C., Liu, M., Chen, X., & Chen, J. X. (2020a). Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(6), 749–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01541-4

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Verona within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. We received funding from Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca (MUR), Bando FISR 2020 COVID (2021–2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Raccanello, D., Rocca, E., Vicentini, G. et al. Eighteen Months of COVID-19 Pandemic Through the Lenses of Self or Others: A Meta-Analysis on Children and Adolescents’ Mental Health. Child Youth Care Forum 52, 737–760 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-022-09706-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-022-09706-9