Abstract

This paper investigates the effects of bargaining power on downstream firms’ profits. Consider a vertically related industry consisting of one upstream and two downstream firms, the latter having different marginal costs. Each pair bargains over a linear wholesale price, and then the downstream firms engage in Cournot competition. We show that the inefficient downstream firm may benefit from an increase in the bargaining power of the upstream firm. Furthermore, we obtain similar results when each downstream firm trades with its exclusive upstream agent, under non-linear demand function, or when downstream firms compete in price.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Cai and Li (2014) consider how political interaction between policymakers and domestic and foreign firms endogenously determines tariff rates.

Matsushima (2015) presents numerous real-world cases where buyers encourage suppliers to organize collective associations to negotiate with them although this would weaken the buyers’ bargaining power.

Grennan (2013) uses a bilateral Nash Bargaining to empirically analyze bargaining and price discrimination in the medical device market.

In contrast, Bonnet and Dubois (2010) find that manufacturers use two-part tariff contracts with resale price maintenance in the bottled water retail market in France. Villas-Boas (2007) also obtains results consistent with non-linear pricing by manufacturers or high bargaining power of retailers in the yogurt market in the US.

Christou and Papadopoulos (2015), in contrast, show that by correcting for payoffs and outside options in Chen (2003), the profit of the dominant retailer never decreases with buyer power. Matsushima and Yoshida (2016) find that the profit of the dominant retailer may decrease with buyer power when the dominant retailer works as sales promoter.

Dertwinkel-Kalt et al. (2015) consider a vertically related market with downstream firms that have different input efficiencies, and they find that a higher input price benefits a subset of relatively efficient downstream firms.

In management, Iyer and Villas-Boas (2003) investigate bargaining over the terms of trade between manufacturers and retailers in distribution channels. They find that when the manufacturer’s bargaining power goes from its lower to upper limit, the manufacturer’s profit first increases and subsequently decreases. Matsushima (2015) considers a Hotelling duopoly model with buyer-supplier negotiations and product positioning choices of downstream firms, and finds that a downstream firm’s profit is not always improved if it strengthens its bargaining power with its exclusive supplier.

Following Horn and Wolinsky’s (1988b) interpretation, this setting can be viewed as a situation in which the workers join forces for the purpose of bargaining. That is, suppose for example that one of the workers is authorized to represent both. When the labor market is not completely flexible (e.g., Japan), or workers must incur high switching costs, it is difficult for the low wage firm’s worker to move to the high wage firm.

We provide a numerical example of a non-linear demand function when the upstream market consists of exclusive suppliers in the next section.

We discuss implications of when disagreement profits come from the monopoly profit of the other downstream firms in the Sect. 5.

Matsumura and Yamagishi (2017) find that incumbents can have incentive to strengthen regulations, which affect the cost of all firms equally, depending on the demand condition.

This is also true when there are two upstream agents in the next section.

This assumption is not essential because the results are qualitatively the same if we consider the case where downstream firms do not incur any costs expect input prices, while each upstream firm faces a constant marginal cost of production.

Fanti (2016) analyzes the effects of two-sided cross-ownership structures in a Cournot duopoly with firm-specific unions, and shows that an increase in the degree of two-sided cross-ownership reduces wage, which implies that cross-ownership and bargaining power have a similar effect on wage.

References

Aghadadashli H, Dertwinkel-Kalt M, Wey C (2016) The Nash bargaining solution in vertical relations with linear input prices. Econ Lett 145:291–294

Basak D, Marjit S, Mukherjee A (2016) Upstream market power and downstream profits under convex costs, mimeo

Binmore K, Rubinstein A, Wolinsky A (1986) The Nash bargaining solution in economic modelling. RAND J Econ 17(2):176–188

Bonnet C, Dubois P (2010) Inference on vertical contracts between manufacturers and retailers allowing for nonlinear pricing and resale price maintenance. RAND J Econ 41(1):139–164

Cai D, Li J (2014) Protection versus free trade: lobbying competition between domestic and foreign firms. South Econ J 81(2):489–505

Chen Z (2003) Dominant retailers and the countervailing-power hypothesis. RAND J Econ 34(4):612–625

Christou C, Papadopoulos K (2015) The countervailing power hypothesis in the dominant firm-competitive fringe model. Econ Lett 126:110–113

Crawford G, Yurukoglu A (2012) The welfare effects of bundling in multichannel television markets. Am Econ Rev 102(2):643–685

DeGraba P (1990) Input market price discrimination and the choice of technology. Am Econ Rev 80(5):1246–1253

Dertwinkel-Kalt M, Haucap J, Wey C (2015) Raising rivals’ cost through buyer power. Econ Lett 126:181–184

Dowrick S (1989) Union-oligopoly bargaining. Econ J 99(398):1123–1142

Draganska M, Klapper D, Villas-Boas S (2010) A larger slice or a larger pie? An empirical investigation of bargaining power in the distribution channel. Mark Sci 29(1):57–74

Fanti L (2016) Interlocking cross-ownership in a unionised duopoly: when social welfare benefits from “more collusion”. J Econ 119(1):47–63

Farmakis-Gamboni S, Prentice D (2011) When does reducing union bargaining power increase productivity? Evidence from the Workplace Relations Act. Econ Rec 87(279):603–616

Freeman R, Medoff J (1984) What do unions do?. Basic Books, New York

Gaudin G (2016) Pass-through, vertical contracts, and bargains. Econ Lett 139:1–4

Gaudin G (2017) Vertical bargaining and retail competition: What drives countervailing power? Econ J (forthcoming)

Grennan M (2013) Price discrimination and bargaining: empirical evidence from medical devices. Am Econ Rev 103(1):145–177

Grout PA (1984) Investment and wages in the absence of binding contracts: A Nash bargaining approach. Econometrica 52(2):449–460

Han TD, Mukherjee A (2017) Labor unionization structure, innovation, and welfare. J Inst Theor Econ 173(2):279–300

Haucap J, Wey C (2004) Unionisation structures and innovation incentives. Econ J 114(494):149–165

Hirsch B (2004) What do unions do for economic performance? J Labor Res 25:415–455

Ho K, Lee R (2015) Insurer competition in health care markets (No. w19401). National Bureau of Economic Research

Horn H, Wolinsky A (1988a) Bilateral monopolies and incentives for merger. RAND J Econ 19(3):408–419

Horn H, Wolinsky A (1988b) Worker substitutability and patterns of unionisation. Econ J 98(391):484–497

Iozzi A, Valletti T (2014) Vertical bargaining and countervailing power. Am Econ J Microecon 6(3):106–135

Iyer G, Villas-Boas JM (2003) A bargaining theory of distribution channels. J Mark Res 40(1):80–100

Koskela E, Schob R (1999) Does the composition of wage and payroll taxes matter under Nash bargaining? Econ Lett 64(3):343–349

Lerner J, Tirole J (2015) Standard-essential patents. J Polit Econ 123(3):547–586

Li Y, Shuai J (2016) Licensing essential patents: the non-discriminatory commitment and hold-up, working paper

Lopez MC, Naylor RA (2004) The Cournot–Bertrand profit differential: a reversal result in a differentiated duopoly with wage bargaining. Eur Econ Rev 48(3):681–696

Machin SJ (1991) Unions and the capture of economic rents: an investigation using British firm-level data. Int J Ind Org 9:261–274

Matsumura T, Yamagishi A (2017) Lobbying for regulation reform by industry leaders. J Regul Econ (forthcoming)

Matsushima N (2015) Do poor procurement conditions always lead to poor performances? The interplay between procurement conditions and product positions. mimeo

Matsushima N, Yoshida S (2016) The countervailing power hypothesis when dominant retailers function as sales promoters. ISER Discussion Paper No. 981, Institute of Social and Economic Research, Osaka University

Milliou C, Petrakis E (2007) Upstream horizontal mergers, vertical contracts, and bargaining. Int J Ind Org 25(5):963–87

Mukherjee A (2008) Unionised labour market and strategic production decision of a multinational. Econ J 118(532):1621–1639

Mukherjee A, Wang LF (2013) Labour union, entry and consumer welfare. Econ Lett 120(3):603–605

Rubinstein A (1982) Perfect equilibrium in a bargaining model. Econometrica 50(1):97–109

Seade J (1985) Profitable cost increases and the shifting of taxation: equilibrium response of markets in oligopoly (No. 260). University of Warwick, Department of Economics

Singh N, Vives X (1984) Price and quantity competition in a differentiated duopoly. RAND J Econ 15:546–554

Symeonidis G (2010) Downstream merger and welfare in a bilateral oligopoly. Int J Ind Organ 28(3):230–243

Van der Ploeg F (1987) Trade unions, investment, and employment: a non-cooperative approach. Eur Econ Rev 31(7):1465–1492

Vetter H (2017) Pricing and market conduct in a vertical relationship. J Econ 121:239–253

Villas-Boas S (2007) Vertical contracts between manufacturers and retailers: inference with limited data. Rev Econ Stud 74:625–652

Zanchettin P (2006) Differentiated duopoly with asymmetric costs. J Econ Manag Strategy 15(4):999–1015

Ziss S (1995) Vertical separation and horizontal mergers. J Ind Econ 43(1):63–75

Acknowledgements

I am especially grateful to Noriaki Matsushima for his valuable advice. I would also like to thank Koki Arai, Keisuke Hattori, Arijit Mukherjee, and the participants of the Japanese Economic Association Conference (Nagoya University) and the seminar participants at Shinshu University for their very useful comments. The author acknowledges the financial support from Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows, Grant Number 16J02442. All remaining errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix: Proofs

Appendix: Proofs

Proof of Lemma 1

Differentiating \(w_1^{*}\) with respect to \(\theta \), we have

Differentiating \(w_2^{*}\) with respect to \(\theta \), we have

Similarly, we have

which proves the lemma. \(\square \)

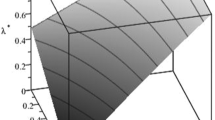

Proof of Proposition 1

Differentiating \(q_1^{*}\) with respect to \(\theta \), we have

Similarly, differentiating \(q_2^{*}\) with respect to \(\theta \), we have

This expression is positive if and only if

We now show that the interval between this lower bound and the upper bound of the interior solution condition is nonempty. Comparing these two values, we have

which gives the condition for Proposition 1. This completes the proof of the proposition. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 2

Differentiating \(Q^{*}\) with respect to \(\theta \), we have

Similarly, we have

Note that \(p^{*}-c_1+q_1^{*}>p^{*}-c_2+q_2^{*}>0\). Since \(\left| \frac{d q_1^{*}}{d \theta }\right| >\frac{d q_2^{*}}{d \theta }\), the sign of Eq. (39) becomes negative. \(\square \)

Proof of Lemma 2

Differentiating \(w_i^{**}\) with respect to \(\theta \), we have

Similarly, we have

which proves the lemma. \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 3

Differentiating \(q_1^{**}\) with respect to \(\theta \), we have

The numerator of the expression can be written as follows:

which proves the first part of the proposition.

Similarly, differentiating \(q_2^{**}\) with respect to \(\theta \), we have

This expression is positive if and only if

We now show that the interval between this lower bound and the upper bound of the interior solution condition is nonempty.

This completes the proof of the proposition. \(\square \)

Proof of Lemma 3

Differentiating \(w_1^{B}\) with respect to \(\theta \), we have

Similarly, we have

which proves the lemma. \(\square \)

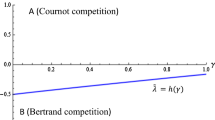

Proof of Proposition 4

Differentiating \(q_1^{B}\) with respect to \(\theta \), we have

Note that we used Lemma 3 to get the inequality on the second line.

We can relatively easy derive the sufficient condition for the result. Applying the mean-value theorem, for some \(\hat{\theta }\in (0,1)\), we have

The condition that the left-hand side of the above expression is positive is

We can confirm that the interval between the above threshold value of \(\alpha \) and that of the interior solution condition is nonempty. That is,

\(\square \)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yoshida, S. Bargaining power and firm profits in asymmetric duopoly: an inverted-U relationship. J Econ 124, 139–158 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-017-0563-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-017-0563-3