Abstract

Background

First-line rituximab therapy together with chemotherapy is the standard care for patients with advanced follicular B-cell lymphoma, as rituximab together with chemotherapy prolongs progression-free and overall survival (Herold et al. 2007; Marcus et al. 2005). However, as not all patient subgroups benefit from combined immuno-chemotherapy, we asked whether the microenvironment may predict benefit from rituximab-based therapy.

Design

To address this question, we performed a retrospective immunohistochemical analysis on pathological specimens of 18 patients recruited into a randomized clinical trial, where patients with advanced follicular lymphoma were randomized into either chemotherapy or immuno-chemotherapy with rituximab (Herold et al. 2007).

Results

We show here that rituximab exerts beneficial effects, especially in the subgroup of follicular lymphoma patients with low intrafollicular CD3, CD5, CD8, and ZAP70 and high CD56 and CD68 expression.

Conclusion

Rituximab may overcome immune-dormancy in follicular lymphoma in cases with lower intrafollicular T-cell numbers and higher CD56 and CD68 cell counts. As this was a retrospective analysis on a small subgroup of patients, these data need to be corroborated in larger clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the most frequent indolent lymphoma diagnosed. In limited stages, radiation-based therapy is thought to have curative potential. In advanced stages, when patients lack symptoms, watch and wait strategy is applied, whereas chemotherapy is the therapy of choice when treatment is needed (Yuda et al. 2016). Over decades, no progress had been seen in the therapy of advanced FL. The introduction of rituximab has changed the therapy of follicular lymphomas (FL) significantly, in that the combined immuno-chemotherapy not only prolongs progression- and event-free survival, but more importantly, overall survival (Herold et al. 2007; Marcus et al. 2008). Transformation into high-grade diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is observed in approx. 4% after 5 years in rituximab-treated patients, which seems lower than in the pre-rituximab era (Janikova et al. 2018).

Predictive factors that discriminate patients who might have a higher benefit from anti-CD20 therapy are not known. Serum concentration of APRIL or low recovery of IgG has been associated with poor survival (Kusano et al. 2018; Li et al. 2008; Taskinen et al. 2007). In contrast, Blaker et al. found that a higher number of intrafollicular CD68-positive macrophages was associated with a higher likelihood of transformation of follicular lymphoma patients into aggressive B-cell lymphoma (Blaker et al. 2016). In their study, all patients had been treated with rituximab-based protocols. However, our study addressed the difference between a small cohort of follicular lymphoma patients treated with rituximab-based chemotherapy and compared this with the cohort treated with chemotherapy only. Both studies thus focused on different issues.

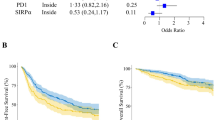

Our study suffers from small numbers, and we used a criterion of p < 0.05 for nominal statistical significance. Therefore, the data presented in this paper need to be interpreted with caution. However, the patients were balanced between the two arms of the original protocol, and the clinical outcome of the 18 patients analyzed here reflected the original trial. As the numbers are small, the data need to be confirmed in larger trials. For such future trials, we propose that the levels as determined for each antigen in the present study (see suppl. Table 3) may be applied as cut-off values since we here demonstrated that the cohort of 18 patients analyzed was representative for the whole trial (see Fig. 1). Naturally, as the chemotherapy given in this trial is not used any more (MCP), we cannot rule out that the herein observed rituximab-based immune activating effect would also be observed when using other chemotherapy regimens such as CHOP or bendamustine. It would also be interesting to apply—in addition to the markers analyzed here—the mutational load of the respective samples, as given in the m7-FLIPI (Pastore et al. 2015).

Taken together, we show here that rituximab exerts beneficial effects especially in the subgroup of follicular lymphoma patients with low intrafollicular CD3, CD5, ZAP70 and CD8, and high CD56 and CD68 expression. Although the study by Dave et al. did not use immunohistology (Dave et al. 2004), they showed that lower T cell and higher macrophage cell signature were both associated with worse prognosis in advanced follicular lymphoma. Our study, therefore, suggests that rituximab therapy could overcome the worse prognostic feature of lower T-cell and higher macrophage infiltration in follicular lymphoma. As this was a retrospective analysis on a small subgroup of patients, these data need to be corroborated in larger clinical trials. Whether rituximab resistance may be overcome by higher dosages of CD20-specific antibodies must be addressed in prospective trials. A hint could be the so-called GADOLIN trial, in which rituximab-resistant patients with indolent lymphomas were randomly assigned to either bendamustine alone or bendamustine plus obinutuzumab that was given at a significant increased dosage as compared to the previously applied rituximab (Sehn et al. 2016).

Notes

The study had been registered as East German Study Group Hematology and Oncology Trial 39 and at ClinicalTrials.gov (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/) under ID 00269113.

References

Blaker YN, Spetalen S, Brodtkorb M et al (2016) The tumour microenvironment influences survival and time to transformation in follicular lymphoma in the rituximab era. Br J Haematol 175:102–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14201

Canioni D, Salles G, Mounier N et al (2008) High numbers of tumor-associated macrophages have an adverse prognostic value that can be circumvented by rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma enrolled onto the GELA-GOELAMS FL-2000 trial. J Clin Oncol 26:440–446. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2007.12.8298

Carbone A, Gloghini A, Cabras A, Elia G (2009) The Germinal centre-derived lymphomas seen through their cellular microenvironment. Br J Haematol 145:468–480. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07651.x

Dave SS, Wright G, Tan B et al (2004) Prediction of survival in follicular lymphoma based on molecular features of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. N Engl J Med 351:2159–2169

Du J, Lopez-Verges S, Pitcher BN et al (2014) CALGB 150905 (Alliance): rituximab broadens the antilymphoma response by activating unlicensed NK cells. Cancer Immunol Res 2:878–889. https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.cir-13-0158

Fischer L, Penack O, Gentilini C, Nogai A, Muessig A, Thiel E, Uharek L (2006) The anti-lymphoma effect of antibody-mediated immunotherapy is based on an increased degranulation of peripheral blood natural killer (NK) cells. Exp Hematol 34:753–759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exphem.2006.02.015

Glas AM, Knoops L, Delahaye L et al (2007) Gene-expression and immunohistochemical study of specific T cell subsets and accessory cell types in the transformation and prognosis of follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 25:390–398

Harjunpaa A, Taskinen M, Nykter M et al (2006) Differential gene expression in non-malignant tumour microenvironment is associated with outcome in follicular lymphoma patients treated with rituximab and CHOP. Br J Haematol 135:33–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06255.x

Herold M, Haas A, Srock S et al (2007) Rituximab added to first-line mitoxantrone, chlorambucil, and prednisolone chemotherapy followed by interferon maintenance prolongs survival in patients with advanced follicular lymphoma: an East German Study Group Hematology and Oncology Study. J Clin Oncol 25:1986–1992

Herold M, Scholz CW, Rothmann F, Hirt C, Lakner V, Naumann R (2015) Long-term follow-up of rituximab plus first-line mitoxantrone, chlorambucil, prednisolone and interferon-alpha as maintenance therapy in follicular lymphoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 141:1689–1695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-015-1963-9

Hilchey SP, Hyrien O, Mosmann TR et al (2009) Rituximab immunotherapy results in the induction of a lymphoma idiotype-specific T-cell response in patients with follicular lymphoma: support for a “vaccinal effect” of rituximab. Blood 113:3809–3812. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2008-10-185280

Huet S, Tesson B, Jais JP et al (2018) A gene-expression profiling score for prediction of outcome in patients with follicular lymphoma: a retrospective training and validation analysis in three international cohorts. Lancet Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(18)30102-5

Janikova A, Bortlicek Z, Campr V et al (2018) The incidence of biopsy-proven transformation in follicular lymphoma in the rituximab era. A retrospective analysis from the Czech Lymphoma Study Group (CLSG) database. Ann Hematol 97:669–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-017-3218-0

Kusano Y, Yokoyama M, Inoue N et al (2018) Delayed recovery of serum immunoglobulin G is a poor prognostic marker in patients with follicular lymphoma treated with rituximab maintenance. Ann Hematol 97:289–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-017-3175-7

Laurent C, Muller S, Do C et al (2011) Distribution, function, and prognostic value of cytotoxic T lymphocytes in follicular lymphoma: a 3-D tissue-imaging study. Blood 118:5371–5379. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-04-345777

Li YJ, Li ZM, **a ZJ et al (2015) High APRIL but not BAFF serum levels are associated with poor outcome in patients with follicular lymphoma. Ann Hematol 94:79–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-014-2173-2

Liu S, Chen B, Burugu S et al (2017) Role of cytotoxic tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in predicting outcomes in metastatic her2-positive breast cancer: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2085

Marcus R, Imrie K, Belch A et al (2005) CVP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CVP as first-line treatment for advanced follicular lymphoma. Blood 105:1417–1423

Marcus R, Imrie K, Solal-Celigny P et al (2008) Phase III study of R-CVP compared with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone alone in patients with previously untreated advanced follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 26:4579–4586

Pastore A, Jurinovic V, Kridel R et al (2015) Integration of gene mutations in risk prognostication for patients receiving first-line immunochemotherapy for follicular lymphoma: a retrospective analysis of a prospective clinical trial and validation in a population-based registry. Lancet Oncol 16:1111–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(15)00169-2

Perez EA, Ballman KV, Tenner KS, Thompson EA, Badve SS, Bailey H, Baehner FL (2016) Association of Stromal Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes With Recurrence-Free Survival in the N9831 Adjuvant Trial in Patients With Early-Stage HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncolo 2:56–64. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3239

Sehn LH, Chua N, Mayer J et al (2016) Obinutuzumab plus bendamustine versus bendamustine monotherapy in patients with rituximab-refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (GADOLIN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 17:1081–1093. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30097-3

Taskinen M, Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML, Nyman H, Eerola LM, Leppa S (2007) A high tumor-associated macrophage content predicts favorable outcome in follicular lymphoma patients treated with rituximab and cyclophosphamide-doxorubicin-vincristine-prednisone. Clin Cancer Res 13:5784–5789. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-07-0778

Wahlin BE, Aggarwal M, Montes-Moreno S et al (2010) A unifying microenvironment model in follicular lymphoma: outcome is predicted by programmed death-1–positive, regulatory, cytotoxic, and helper T cells and macrophages. Clin Cancer Res 16:637–650. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-09-2487

Weiner GJ (2010) Rituximab: mechanism of action. Semin Hematol 47:115–123. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminhematol.2010.01.011

Xerri L, Huet S, Venstrom JM et al (2017) Rituximab treatment circumvents the prognostic impact of tumor-infiltrating T cells in follicular lymphoma patients. Hum Pathol 64:128–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2017.03.023

Yuda S, Maruyama D, Maeshima AM et al (2016) Influence of the watch and wait strategy on clinical outcomes of patients with follicular lymphoma in the rituximab era. Ann Hematol 95:2017–2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-016-2800-1

Funding

Supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (KFO210; Ne310/14-1; Ne310/14-2 to AN and AB) and the German José Carreras Leukämie Stiftung (AH06-01, AN).

Funding

Andreas Neubauer and Christian Wilhelm designed the research study. Laura Budau and Roland Moll performed the research. Konstantin Strauch did the statistical analysis. Jörg Jäkel, Carsten Hirt, Gottfried Dölken, Georg Maschmeyer, Ellen Neubauer, Andreas Burchert and Michael Herold contributed essential reagents or tools. Laura Budau and Andreas Neubauer wrote the paper. All authors analyzed the data and agreed on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Georg Maschmeyer reports personal fees from Celgene, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, personal fees from Janssen-Cilag, not related to the current paper. Andreas Neubauer has received honoraria from Medupdate GmbH, not related to the current paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Budau, L., Wilhelm, C., Moll, R. et al. Low number of intrafollicular T cells may predict favourable response to rituximab-based immuno-chemotherapy in advanced follicular lymphoma: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 145, 2149–2156 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-019-02961-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-019-02961-9