Abstract

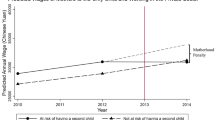

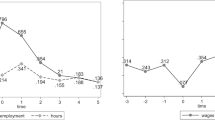

The chapter is dedicated to the analysis of monthly and hourly wages of mothers and non-mothers in Russia. Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Survey HSE is used for the data basis to estimate the motherhood wage penalty between working women without children and working mothers. The study discloses 11% penalty for mothers in their hourly wages on average in Russia in the period of 2000–2015. Despite same level of education, tenure, qualification women with two and more children are paid considerably less than women without children. The small age of the youngest child affects the working hours which reduce the monthly wage considerably, but it does not impact the hourly wage penalty. The chapter shows that the motherhood wage penalty in Russia is lower than in Germany, UK or the US especially for the mothers with pre-school age children.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Harry Becker’s theory of human capital explains, first the existence of a gender pay gap due to the uneven distribution of men and women by industry and occupation (Becker 1964; Mincer and Polachek 1974). In accordance with this approach, women occupy positions in those sectors of economics and give preference to those professions that require less investment in human capital, since the period during which they pay off is shorter than that of men (women spends less time on labor market than men). Companies, for their part, can also give preference to men and avoid hiring women (especially with young children), to places where the presence and application of a large amount of specific skills is required (since women may also have interruptions in work due to the birth of children).

- 2.

- 3.

Number of years a person works at the same company/firm/organization.

References

Aisenbrey S, Evertsson M, Grunow D (2009) Is there a career penalty for mothers’ timeout? A comparison of Germany, Sweden and the United States. Soc Forces 88(2):573–606

Almuendo-Dorates C, Kimmel, J (2004) Themotherhood wage gap for women in the United States: the importance of collage and fertility delay. Working Paper E2004/07

Anderson D, Blinder M, Krause K (2002) The motherhood wage penalty: which mothers pay it and why? Am Econ Rev 92(2):354–358

Anderson D, Binder M, Krause K (2003) The motherhood wage penalty revisited: experience, heterogeneity, work effort and work-schedule flexibility. Ind Labour Relat Rev 56(2):273–294

Avellar S, Smock PJ (2003) Has the price of motherhood declined over time? A cross-cohort comparison of the motherhood wage penalty. J Marriage Fam 65(3):597–607

Becker G (1964) Human capital: a theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Becker G (1971) The economics of discrimination. The University of Chicago, Chicago

Bedi A, Majilla T, Rieger M (2018) Gender norms and the motherhood penalty: experimental evidence from India. IZA Discussion Paper No. 11360, Bonn, Germany

Biryukova & Makarentseva 2017. Estimations of motherhood penalty in Russia, population and economics. Popul Econ 1(1):50–70 (in Russian)

Budig M, England P (2001) The wage penalty for motherhood. Am Sociol Rev 66:204–225

Budig M, Misra J, Boeckmann I (2012) The motherhood penalty in cross-national perspective: The importance of work–family policies and cultural attitudes. Soc Polit: Int Stud Gend, State & Soc 19(2) (Summer):163–193. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxs006

Corinaldi M (2019) Motherhood in the workplace: a sociological exploration into the negative performance standards and evaluations of full-time working mothers. Philol 11(1):13–16

Cukrowska-Torzewska E, Matysiak A (2018) The motherhood wage penalty: a meta-analysis. Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers, 08/2018

Doeringer PB, Piore MJ (1971) Internal labor markets and manpower analysis. ME Sharpe, New York

Domenech M (2005) Employment after motherhood: a Europeen comparison, Labour Econ 12:99–123

Doren C (2019) Which mothers pay a higher price? Education differences in motherhood wage penalties by parity and fertility timing. Sociol Sci 2019(6):684–709

England P, Bearak J, Budig MJ, Hodges MJ (2016) Do highly paid, highly skilled women experience the largest motherhood penalty? Am Sociol Rev 81(6):1161–1189

Gangl M, Ziefle A (2009) Motherhood, labor force behavior, and women’s careers: an empirical assessment of the wage penalty for motherhood in Britain, Germany, and the United States. Demography 46(2):341–369. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0056

Goldberg M (1982) Discrimination, nepotism and long-run wage differentials. Q J Econ 92(2):307–319

Gorbunova E, Karabchuk T, Sukhova A, Nagernyak M, Pankratova V, Pankratova M (2012 ) Women in the Russian labor market after the birth of a child. In: Bulletin of the Russian Monitoring of the Economic Situation and Public Health of the Higher School of Economics (RLMS-HSE). Vol. 2 (in Russian)

Gupta ND, Nina S (2001) Children and career interruptions: the family gap inDenmark. Economica 69(276):609–629. London School of Economics and Political Science

Kahn JR, García-Manglano J, Bianchi SM (2014) The motherhood penalty at midlife: long-term effects of children on women’s careers. Fam Relat 76:56–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12086

Karabchuk T, Nagernyak M (2013) Determinants of employment for mothers in Russia. J Soc Policy Stud 11(1):25–48 (in Russian)

Kelley H, Galbraith Q, Strong J. (2020) Working moms: motherhood penalty or motherhood return? J Acad Libr 46(1)

Klerman JA, Leibowitz A (1999) Job continuity among new mothers. Demogr 36:145–155

Kühhirt M, Ludwig V (2012) Domestic work and thewage penalty form otherhood in West Germany. J Marriage Fam 74(1):186–200. Hoboken, NJ

Kunze A, Matte E (2004) Wage dips and drops around first birth. IZA Discussion Paper No. 1011

Lindbeck A, Snower DJ (2002) The insider-outsider theory: a survey. IZA Discussion paper series. 534

Luhr S (2020) Signaling parenthood: managing the motherhood penalty and fatherhood premium in the U.S. service sector. Gend & Soc 34(2):259–283

Lundberg S, Rose E. (2000). Parenthood and the earnings of married men and women. Labour Econ (7):689–710

Lutter M, Schröder M (2019). Is there a motherhood penalty in academia? The gendered effect of children on academic publications in German Sociology. Eur Sociol Rev 36:442–459

Möhring K (2017) Is there a motherhood penalty in retirement income in Europe? The role of life course and institutional characteristics. Ageing Soc 38:2560–2589

Miller A (2011) The effects of motherhood timing on career path. J Popul Econ 24(3):1071–1100. Retrieved December 3, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41488341

Mincer J, Polachek S (1974) Family investment in human capital: earnings of women. J Polit Econ 82(2):S76–S108

Mu Z, **e Y (2016) ‘Motherhood penalty’ and ‘fatherhood premium’? Fertility effects on parents in China. Demogr Res 35:1373–1410

Napari S (2007) Is there a motherhood wage penalty in the Finnish private sector? ETLA, Elinkeinoelämän Tutkimuslaitos, The Research Institute of the Finnish Economy, Helsinki

Neumark D, Korenman S (1994) Sources of bias in women’s wage equations: results using sibling data. J Hum Resour 29:379–405

Nielsen HS, Simonsen M, Verner M (2004) Does the gap in family-friendly policies drive the family gap? Scand J Econ 106:721–744

Nivorozhkina L, Nivorozhkin A (2008) The wage costs ofmotherhood: whichmothers are better off and why. (IAB Discussion Paper: Beiträge zum wissenschaftlichen Dialog aus dem Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung, 26/2008). Nürnberg: Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufs forschung der Bundesagentur für Arbeit (IAB). https://nbnresolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-307627

Nizalova OY, Sliusarenko T (2013) Motherhood wage penalty in times of transition. IZA Discussion Papers 7810, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA)

Nizalova OY, Sliusarenko T, Shpak S (2016) The motherhood wage penalty in times of transition. J Comp Econ, Elsevier 44(1):56–75

Nizalova OY (2017) Motherhood wage penalty may affect pronatalist policies. IZA World of Labor, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), pp. 359–359, May

OECD (2012) Closing the gender gap: act now. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264179370-en

Oshchepkov A (2007) Gender differences in wages, wages in Russia. Evolution and differentiation. HSE Publishing House, Chapter 5 (in Russian)

Payet A, Sinyavskaya O (2011) Employment of women in France and in Russia: the role of children and gender attitudes. Demoscope (449) (in Russian)

Pankratova M (2013) Satisfaction of Russian women with children and without children with work and life. Econ Sociol 14(2):88–110 (in Russian)

Petersen T, Penner AM, Høgsnes G (2011) The male marital wage premium: sorting vs. differential pay. ILR Rev 64(2):283–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979391106400204

Petersen T, Penner A, Høgsnes G (2014) From motherhood penalties to husband premia: the new challenge for gender equality and family policy, lessons from norway. Am J Sociol 119(5):1434–512. https://doi.org/10.1086/674571

Rosen S (1987) The theory of equalizing differences. In: Ashenfelter O, Layard R (eds) BT Handbook of labor economics vol 1, Issue 12. Elsevier, pp 641–692. https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:labchp:1-12

Roshchin S, Solntsev S (2006) Who overcomes the “glass ceiling”: vertical gender segregation in the Russian economy/preprints. High School of Economics. Series WP4 “Sociology of markets” (03) (in Russian)

Rzhanitsyna L (1997) There is no way to overcome the crisis without solving the “female issue”, women and the labor market. Library of union activist. M., Profizdat (6) (in Russian)

Savinskaya O. (2011) Caring for the children of working Muscovites. Sociol Stud (1) (in Russian)

Sinyavskaya O, Zakharov S, Kartseva M. (2007) Behavior of women in the labor market and childbearing in modern Russia/Parents and children, men and women in the family and society/Under the scientific, T Malevoy, O Sinyavskaya (eds). Independent Institute for Social Policy. M.: IISP (in Russian)

Sommerfeld K (2008) Older babies - more active mothers?: How maternal labor supply changes as the child grows, No 143, SOEP papers on multidisciplinary panel data research. DIWBerlin, The German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP). https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:diw:diwsop:diw_sp143

Yu W, Kuo JC (2017) The motherhood wage penalty by work conditions: how do occupational characteristics hinder or empower mothers? Am Sociol Rev 82(4):744–769

Van Bavel J, Klesment M (2017) Educational pairings, motherhood, and women’s relative earnings in Europe. Demogr 54(6):2331–2349

Viitanen T (2004) The impact of children on female earnings in Britain. Discussion Paper. DIW Berlin and University of Warwick

Waldfogel J (1997) The effect of children on women’s wages. Am Sociol Rev 62(2):209–217

Waldfogel J (1998a) The family gap for young women in the United States and Britain: can maternity leave make a difference? J Labor Econ 16:505–545

Waldfogel J (1998b) Understanding the ‘family gap’ in pay for women with children. J Econ Perspect 12:137–156

Zelenskaya LM (2010) Problems of gender inequality in wages in the Russian labour Market. 542 Manger 5–6(9–10):72–73. (in Russian). Зеленская Л. М. 2010. Проблемы гендерного равенства в оплате труда на российском рынке труда. Управленец. 5–6(9–10):С. 72–73.

Zhao M (2018) From motherhood premium to motherhood penalty? Heterogeneous effects of motherhood stages on women’s economic outcomes in urban China. Popul Res Policy Rev 37:967–1002

Zhitnikova EA (2010) Gender discrimination and its peculiarities in Russia. Sci Note. Orel. GIET2. (in Russian). Житникова Е. А. 2010. Гендерная дискриминация и особенности ее проявления в России. Научные записки ОрелГИЭТ. 2. http://www.orelgiet.ru/monah/75jk.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Annex

Annex

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Karabchuk, T., Trach, T., Pankratova, V. (2021). Motherhood Wage Penalty in Russia: Empirical Study on RLMS-HSE Data. In: Karabchuk, T., Kumo, K., Gatskova, K., Skoglund, E. (eds) Gendering Post-Soviet Space. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-9358-1_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-9358-1_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-15-9357-4

Online ISBN: 978-981-15-9358-1

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)