Abstract

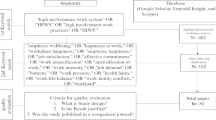

This study proposes and tests empirically a configural asymmetric theory of the antecedents to hospitality employee happiness-at-work and managers’ assessments of employees’ quality of work-performance. The study confirms and goes beyond prior statistical findings of small-to-medium effect sizes of happiness-performance relationships. The study merges data from surveys of employees (n = 247) and surveys completed by their managers (n = 43) and by using qualitative comparative analysis via the software program, fsQCA.com. The study analyzes data from Janfusan Fancyworld, the largest (in revenues and number of employees) tourism business group in Taiwan; Janfusan Fancyworld includes tourist hotels, amusement parks, restaurants and additional firms in related service sectors. The findings support the four principles of configural analysis and theory construction: recognize equifinality of different solutions for the same outcome; test for asymmetric solutions; test for causal asymmetric outcomes for very high versus very low happiness and work performance; and embrace complexity. Additional research in other firms and additional countries is necessary to confirm the usefulness of examining algorithms for predicting very high (low) happiness and very high (low) quality of work performance. The implications are substantial that configural theory and research will resolve perplexing happiness-performance conundrums. The study provides algorithms involving employees’ demographic characteristics and their assessments of work facet-specifics which are useful for explaining very high happiness-at-work and high quality-of-work performance (as assessed by managers)—as well as algorithms explaining very low happiness and very low quality-of-work performance. The study is the first to propose and test the principles of configural theory in the contest of hospitality frontline service employees’ happiness-at-work and managers’ assessments of these employees quality of work performances.

Relationships between variables can be non-linear with abrupt switches occurring, so the same “cause” can, in specific circumstances, produce different effects.

(“The Complexity Turn”, Urry 2005 ).

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Babin BJ, Darden WR, Griffin M (1994) Work and/or fun: measuring Hedonic and utilitarian shop** value. J Consum Res 20(4):644–656

Baker J (1986) The role of the environment in marketing services: the consumer perspective. In: Czepiel JA, Congram C, Shanahan J (eds) In the services challenge: integrating for competitive advantage. American Marketing Association, Chicago, IL, pp. 79–84

Barsade S (2000) The ripple effect: emotional contagion in groups. Working paper. Yale University Press, Hew Haven, CT. http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=250894 Accessed 7 February 2011.

Barsade S (2002) The ripple effect: emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. Adm Sci Q 47(4):644–676

Bartel CA, Saavedra R (2000) The collective construction of work group moods. Admin Sci Quart 45(2):197–231

Bass FM, Tigert DJ, Lonsdale RT (1968) Market segmentation: group versus individual behavior. J Market Res 5(3):264–270

Bettencourt LA, Brown S (1997) Contact employees: relationships among workplace fairness, job satisfaction, and pro-social service behaviors. J Retail 73(1):39–61

Bettencourt LA, Gwinner KP, Meuter ML (2001) A comparison of attitude, personality, and knowledge predictors of service-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors. J Appl Psychol 86(1):29–41

Bitner MJ (1990) Evaluating service encounters: the effects of physical surroundings and employee responses. J Market 54(4):69–82

Bitner MJ (1992) Servicescapes: the impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. J Market 56(2):57–71

Borman WC, Motowidlo SJ (1993) Expanding the criterion domain to include elements of contextual performance. In: Schmitt N, Borman WC (eds) Personnel selection in organizations. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, pp. 71–98

Choi HJ, Kim YT (2012) Work-family conflict, work-family facilitation, and job outcomes in the Korean hotel industry. Int J Contemp Hospit Manag 24(7):1011–1028

Clark BH (1999) Marketing performance measures: history and interrelationships. J Market Manag 15(8):711–732

Cohen J (1977) Statistical Power Analysis or the Behavioral Sciences. Academic, New York

Collins PH (1990) Black feminist thought: knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Unwin Hyman, Boston, MA

Crosby LA, Evans KR, Cowles D (1990) Relationship quality in services selling: an interpersonal influence perspective. J Mark 54(3):684–781

Donovan RJ, Rossiter JR (1982) Store atmosphere: an environmental psychology approach. J Retail 58(1):34–57

Fisher CD (2010) Happiness at work. Int J Manag Rev 12(4):384–412

Fiss PC (2007) A set theoretic approach to organizational configurations. Acad Manage Rev 32(4):1180–1198

Fiss PC (2011) Building better casual theories: a fuzzy set approach to typologies in organizational research. Acad Manage J 54:393–420

Foxall GR, Greenley GE (1999) Consumers’ emotional responses to service environments. J Bus Res 46(2):149–157

Frijda N (1988) The laws of emotion. Am Psychol 43(5):349–358

Frone MR (2000) Interpersonal conflict at work and psychological outcomes: testing a model among young workers. J Occup Health Psychol 5(2):246–255

Galunic DC, Eisenhardt KM (1994) Reviewing the strategy-structure-performance paradigm. Res Organ Behav 16:215–255

George JM, Jones GR (2002) Understanding and managing organizational behavior, 3rd edn. Prentice-Hall, New Jersey

Gibson JL, Ivancevich JM, Donnelly JH Jr (1994) Organizations: business, structure, processes, 8th edn. Irwin, Boston, MA

Gigerenzer G (1991) From tools to theories: a heuristic of discovery in cognitive psychology. Psychol Rev 98:254–267

Gladwell M (1996) The tip** point: how little things can make a big difference. Little, Brown, New York

Gresov C, Drazin R (1997) Equifinality: functional equivalence in organization design. Acad Manage Rev 22:403–428

Havlena WJ, Holbrook MB (1986) The varieties of consumption experience: comparing two typologies of emotion in consumer behavior. J Consum Res 13(3):394–404

Hepbur VG, Loughoin CA, Barling J (1997) Co** with chronic work stress. In: Gottlieb BH (ed) Coo** with chronic stress. Plenum, New York, pp. 343–366

Hess U, Kirouac G (2000) Emotion expression in groups. In: Lewis MJ, Jeannette M (eds) Handbook of emotions. The Guilford Press, New York, pp. 489–497

Howton FW (1963) Work assignment and interpersonal relations in a research organization: some participant observations. Adm Sci Q 7(4):502–520

Iaffaldano MT, Muchinsky PM (1985) Job satisfaction and job performance: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 97:251–273

Jervis R (1997) System effects. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

Judge TA, Thoresen CJ, Bono JE, Patton GK (2001) The job satisfaction—job performance relationship: a qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol Bull 127:376–407

Karatepe OM (2013) High-performance work practices and hotel employee performance: the mediation of work engagement. Int J Hosp Manag 32:132–140

Katz D, Kahn RL (1978) The social psychology of organizations, 2nd edn. Wiley, New York

Kossek EE, Ozeki C (1998) Work-family conflict, policies, and the job-life satisfaction relationship: a review and directions for organizational behavior-human resources research. J Appl Psychol 83(2):139–149

Kotler P (2000) Marketing management: planning, implementation, and control, 10th edn. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

LePine JA, Erez A, Johnson DE (2002) The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: a critical review and meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol 87:52–65

Lin JC (1998) The influence of meditation to business employee’s emotion management and personal relationship. Unpublished Doctor Dissertation

Lorenz K (1961) Arithmetik und Logik als Spiele. Dissertation. Universitat Kiel, Kiel

Lovaglia MJ, Houser JA (1996) Emotional reactions and status in groups. Am Sociol Rev 61(5):867–883

Lovelock CH (1996) Services marketing, 3rd edn. Prentice-Hall, New Jersey

Lucas JW, Lovaglia MJ (1998) Leadership status, gender, group size, and emotion in face-to-face groups. Sociol Perspect 41(3):617–637

Lyubomirsky S, King LA, Diener E (2005) The benefits of frequent positive affect: does happiness lead to success. Psychol Bull 131:803–855

Machleit KA, Eroglu SA (2000) Describing and measuring emotional response to shop** experience. J Bus Res 49(2):101–111

McClelland DC (1998) Identifying competencies with behavioral-event interviews. Psychol Sci 9:331–3339

Motowidlo SJ, Van Scotter JR (1994) Evidence that task performance should be distinguished from contextual performance. J Appl Psychol 79(4):475–480

Netemeyer RG, Maxham JG III, Pullig C (2005) Conflicts in the work-family interface: links to job stress, customer service employee performance, and customer purchase intent. J Market 69(2):130–143

Ragin CC (1997) Turning the tables: how case-oriented methods challenge variable oriented methods. Compar Soc Res 16(1):27–42

Ragin CC (1999) Using qualitative comparative analysis to study causal complexity. Health Serv Res 34(5, Part 2):1225–1239

Ragin C (2008) Redesigning social inquiry: fuzzy sets and beyond. Chicago University Press, Chicago

Ragin CC (2010) Contentious performances. Am J Soc 115(6):1953–1958

Russell JA, Pratt G (1980) A description of the affective quality attributed to environments. J Pers Soc Psychol 38(2):311–322

Russell JA, Lanius UF (1984) Adaptation level and the affective appraisal of environments. J Environ Psychol 4(2):119–135

Schutte NS, Malouff JM, Bobik C, Coston TD, Greeson C, Jedlicka C, Rhodes E, Wendorf G (2001) Emotional intelligence and interpersonal relations. J Soc Psychol 141(4):523–536

Shostack LG (1985) Planning the service encounter. In: Czepiel JA, Solomon MR, Surprenant CF (eds) The service encounter. Lexington Books, New York, pp. 243–254

Singh J (2000) Performance productivity and quality of frontline employees in service organizations. J Market 64(4):15–34

Singh J, Verbeke W, Rhoads GK (1996) Do organizational practices matter in role stress processes? A study of direct and moderating effects for marketing-oriented boundary spanners. J Market 60(6):69–86

Slack T (1997) Understanding sport organizations: the application of organization theory. Human Kinetics, Windson, ON

Sloan MM (2012) Controlling anger and happiness at work: an examination of gender differences. Gender Work Organ 19:370–391

Spector PE, Jex SM (1998) Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strains: interpersonal conflict at work scale, organizational constraints scale, quantitative workload inventory, and physical symptoms inventory. J Occup Health Psychol 3(4):356–367

Terry DJ, Tonge L, Callan VJ (1995) Employee adjustment to stress: the role of co** resources, situational factors and co** responses. Anxiety Stress Co** 8(1):1–24

Turley LW, Milliman RE (2000) Atmospheric effects on shop** behavior: a review of the experimental evidence. J Bus Res 49(2):193–211

Urry J (2005) The complexity turn. Theor Cult Soc 22(5):1–14

Van de Vliert E, Euwema MC (1994) Agreeableness and activeness as components of conflict behaviors. J Pers Soc Psychol 66(4):674–687

Vroom VH (1964) Work and motivation. Wiley, New York

Warr P (2007) Searching for happiness at work. The Psychologist 20(12):726–729

Wart S, Robertson TS, Zielinski J (1992) Consumer behavior. Scott, Foresman and Company, Illinois

Wirtz J, Bateson JEG (1999) Consumer satisfaction with service: integrating the environment perspective in services marketing into the traditional disconfirmation paradigm. J Bus Res 44(1):55–66

Woodside AG (2013) Moving beyond multiple regression analysis to algorithms: calling for a paradigm shift from symmetric to asymmetric thinking in data analysis and crafting theory. J Bus Res 63:463–472

Woodside AG, Hsu S-Y, Marshall R (2011) General theory of cultures’ consequences on international tourism behavior. J Bus Res 64:785–799

Yoo C, Park J, MacInnis DJ (1998) Effects of store characteristics and in-store emotional experiences on store attitude. J Bus Res 42(3):253–263

Zelenski JM, Murphy SA, Jenkins DA (2008) The happy-productive worker thesis revisited. J Happiness Stud 9:521–537 available online at http://springer.longhoe.net/article/10.1007/s10902-008-9087-4#page-2

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix: Examples of Computing Scores for Complex Antecedent Conditions

Appendix: Examples of Computing Scores for Complex Antecedent Conditions

Consider the following descriptions of five employees. Bob is very young with little education, he is unmarried with no children, he works part-time, he is a new employee, he is very happy-at-work; Bob’s manager rates Bob’s job performance to be very low.

Edwina is very young with little education, unmarried, children at home, she works full-time, three years of working in the firm, she is very unhappy-at-work; Edwina’s manager rates Edwina’s job performance to be very high.

Helen is 54 years old, married, grown children, 18 years working in the firm, working full-time, very little education, working full-time, very happy at work; Helen’s manager rates her job performance to be very high.

Linda is new to the firm, 24 years old, university graduate, married, not children, working full-time, very happy-at-work; Linda’s manager rates her performance to be acceptable but not high, “she has a long way to go but she shows promise.”

Consider the following complex antecedent conditions:

-

Model D: ~age●~education●~married●~children●gender

-

Model R: ~age●~education●~married●children●~gender

-

Model V: ~age●education●married●~children●~gender

-

With ~age = the negation of age (i.e., high score means very young);

-

~education = very low education score

-

~married = not married

-

~children = no children

-

~gender = female (thus, gender = male).

Using the logical “AND” in Boolean algebra, the membership score for the complex statement is equal to the lowest score among the scores for the simple antecedents in the complex statement. Computing the complex antecedent scores for models D, R, and V, for the four employees:

Case | Age | Education | Married | Children | Gender | D | R | V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bob | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

Edwina | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.01 |

Helen | 0.98 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

Linda | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.82 |

Bob’s score for ~age = .0.99; his score for ~education = 0.99; his score for ~married = 0.99; his score for ~children = 0.99; his score for gender = 0.99. Thus, Bob’s score for model D equals 0.99—the lowest score among the five simple antecedent conditions. Here are Linda’s scores for the simple antecedent conditions in Model V: ~age = .94; education = 0.82; married = 0.99; ~children = 0.99; ~gender = 0.99; Linda’s score for model V is equal to the lowest score among the five values (i.e., .82).

Construction of XY plots by hand is possible with the each set of scores for models D, R, and V on the X-axis and the scores for full-time, happiness, and job performance on the Y-axes. Note that full-time equals 0.00 and part-time equals 0.01; “very happy” equals 0.99 and very unhappy equals 0.01; very high performance equals 0.00 and very low performance equals 0.01. With five demographic antecedent conditions, all possible combinations include 32 models for the complex combinations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hsiao, J.PH., Jaw, C., Huan, TC., Woodside, A.G. (2017). The Complexity Turn in Human Resources Theory and Research. In: Woodside, A. (eds) The Complexity Turn. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47028-3_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47028-3_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-47026-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-47028-3

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)