Abstract

Internet surveys are the future of migration studies given that migrants engage more and more often in multidirectional movements and reside in multiple destination countries. The richness of the growing variety of geographical and temporal migrant trajectories pose particular challenges for quantitative researchers studying such spatially dispersed populations for which sampling frames are not available. The Web-based Respondent Driven Sampling (RDS) method addresses many of the challenges occurring in such a context. However, its implementation is not an easy task and does not succeed in all migratory settings. The goal of this chapter is to outline the opportunities and challenges associated with using Web-based RDS for researching migrant populations. While the RDS method can be powerful in fact-to-face interviews, its usefulness in Internet surveys is debatable. We examine this issue by using the example of a survey of Polish multiple migrants worldwide conducted in 2018–2019. We outline observations from the fieldwork (selection of seeds, formation of referral chains, etc.), and discuss the challenges of using Web-based RDS by focusing on the barriers to referral chain formation related to RDS assumptions and study design. The observed constraints relate to the definition of a target group, the management of incentives online, and the anonymity issues of online surveys.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Web-based respondent-driven sampling

- Multiple migrants

- Online survey

- Hard-to-survey populations

- Polish migrants

1 Introduction

Migrants are an example of what survey researchers call a “hard-to-survey population” (Tourangeau et al., 2014). Challenges in surveying migrants can occur at various stages of the survey process. In many countries, sample frames for surveying migrants are not available, which makes this group hard-to-sample. If migrant populations are hidden, subject to social stigma or even persecution (as may be the case with undocumented migrants), they also remain hard-to-identify. Migrants also may be hard-to-reach, since they may be highly mobile people or international elites living in gated communities or they may be less privileged migrants living in more vulnerable areas difficult to access by researchers. Additionally, issues such as language barriers may make migrants hard-to-persuade to take part in research, and, even once they agree to take participate, hard-to-interview.

These challenges, however, make up for the one of the most fascinating features of migration studies: as researchers we constantly learn about and test-and-try to address these issues. This chapter testifies to this learning process by focusing on a particularly challenging sub-group of migrants—the multiple migrants who have migrated more than once and to more than one destination country. We know relatively little about multiple migrants, but we can assume that they are a rather small population and flexible with respect to changing their destinations (Jancewicz & Salamońska, 2020). Consequently, researching these migrants involves a wide array of challenges related to hard-to-survey populations, which demands an innovative methodological approach beyond the traditional survey methods.

To study multiple migrants from Poland (within the MULTIMIG project, which we describe in more detail in one of the following sections on survey design and implementation), we employed a Web-based survey to deal with their spatial dispersion and high mobility. Due to the lack of a sampling frame, we decided to use the respondent-driven sampling (RDS) method (originally introduced by Douglas Heckathorn, see Heckathorn, 1997) with the aim to improve the representativeness of the sample. Such an approach, referred to in the literature as Web-based RDS (Bauermeister et al., 2012), seemed to address most of the challenges involved in studying Polish multiple migrants. Owing to implementation of the Web-based RDS survey, we learned about the characteristics of the mobility of Polish multiple migrants, but above all, we learned about the extent to which Web-based RDS can actually work in the field in general, and in the case of this group in particular.

Thus, the goal of this chapter is to address the challenges and opportunities of using the Web-based RDS method for migration studies and beyond. Although in our particular case, we used the method to analyze international mobility, we believe that it can be of value more generally in a variety of thematic contexts.

The chapter proceeds as follows: first, it introduces the RDS survey method by pointing to the differences between traditional and Web-based approaches and by outlining the strengths of the Web-based RDS approach for the migration research. Next, we describe the research design of the MULTIMIG project and provide an overview of the survey sample we obtained. Then, we turn to our assessment of the effectiveness of the Web-based RDS method in our study of multiple migrants. Finally, we outline the challenges to overcome and the outlook for future uses of Web-based RDS in studies on migration and beyond.

2 Respondent Driven Sampling in Migration Studies: Face-to-Face and Web-Based Approaches

2.1 RDS Assumptions

The RDS method is a modified version of chain-referral sampling with a double incentive system. Respondents are remunerated for taking part in the research (primary incentive) and for recruiting a peer (secondary incentive). This system facilitates the recruitment process and reduces some of the biases that have been found to occur with “traditional” snowball sampling (for an elaboration, see Heckathorn, 1997). RDS starts with a selection of a small number of individuals (so-called seeds) who initiate the recruitment chains. These initial seeds should be diversified with regard to the characteristics that influence how social ties are formed (including, age, social standing, and geographical location). They also should possess wide networks and be highly motivated to take part in the research (Wejnert & Heckathorn, 2008). The seeds and subsequent recruiters are allowed to recruit only a limited number of persons each (usually two to three) by physically passing them coupons with a unique code (Tyldum & Johnston, 2014: 13). Therefore, the recruitment within chains proceeds without the intervention of researchers, and is based on the social networks of respondents. Consequently, face-to-face RDS surveys have limited geographical coverage. Respondents, while physically passing coupons to persons they invite to the study, have a tendency to approach the people living in their neighborhood (McCreesh et al., 2011). At the same time, RDS is not only a recruitment method, but also a broader analytical approach based on a number of rigorous assumptions that allow for the procurement of unbiased estimators for the studied populations (Heckathorn, 1997, 2007; Volz & Heckathorn, 2008).

The RDS conditions and assumptions relate to the network structure of the studied population (linked also to the definition of the studied group) and the sampling procedure (Gille et al., 2015). First, the population has to be densely networked, and the relations between its members should be reciprocal. The definition of the studied group should be formulated with respect to two interlinked conditions—the members of the studied group should be capable of identifying other members of this group, and they should share some feeling of belonging to this group. Both assumptions are important prerequisites for effective RDS recruitment. Moreover, respondents must be able to report the number of peers in their network who belong to the target population. Researchers use reported information to assess the bias of the obtained RDS data. In the studied group, barriers for contacts and bottlenecks in the network may exist, but the network has to constitute a single component.Footnote 1 Homophily—understood as a tendency of an individual to hold ties with others who are like them—within the network should not be too strong, so to avoid the tendency that individuals will only recruit people who are similar to them. Another precondition relates to the sampling procedure that individuals must randomly recruit peers from their networks. These two conditions ensure that a fundamental precondition of RDS is met: that the characteristics of the final sample are independent of the seeds’ selection. However, this precondition can be guaranteed only if the chains in the sample are long enough (for a more elaborate description of the RDS assumptions, see the introduction in Tyldum and Johnston (2014), Heckathorn (1997) and Volz and Heckathorn (2008)).

The RDS method was designed to study populations whose members usually do not want to openly admit their affiliation to the studied group, and thus remain “invisible” to researchers (Heckathorn, 1997). For most such groups, respective registries are incomplete or inexistent, for example, injection drug users, commercial sex workers, and men having sex with men (Malekinejad et al., 2008; Montealegre et al., 2013). The RDS method also has been increasingly used to study migrant populations (Tyldum & Johnston, 2014; Schenker et al., 2014) and has proved to be effective in many contexts, including research on Polish migrants (Tyldum & Johnston, 2014). A comparison of two surveys based on quota sampling and RDS carried out among Ukrainian migrants in the larger Warsaw area demonstrated that the RDS survey provided a more diversified sample with a higher representation of temporary migrants and a broader geographical coverage (Górny & Napierała, 2016). However, it also has been found that the RDS method may lead to an underrepresentation of highly skilled, well-off migrants and those with limited contacts with other migrants (e.g., spouses of natives) (Górny, 2017).

2.2 Web-Based RDS vs Face-to-Face RDS

In many respects, the Web-based RDS procedure is similar to the face-to-face RDS version. However, the recruitment process is based on the virtual ties of respondents, which only partly intersect with their personal, physical social networks. On the one hand, the Web-based approach may involve more dense networks of weaker, virtual ties, and on the other, it may limit the possibilities of recruiting those potential participants who are less embedded in the digitalized world. To begin a Web-based RDS study, researchers identify a limited number of seeds in the target population, to whom they send an individualized link to the online questionnaire. While face-to-face RDS makes use of paper and pencil or computer assisted personal interviews, the Web-based RDS interviewees fill in the questionnaires online. On completion of the questionnaire, the respondents receive e-coupons, which they pass on electronically to other persons in the network. Importantly, the Web-based RDS does not have an interviewer who explains the logics of further recruitment to the study. The Web-based RDS uses a dual incentive system, but, unlike the face-to-face RDS with a “cash in hand” transfer, Web-based RDS respondents can receive remuneration only if they provide their personal details, which may prove to be an issue for some respondents. This problem can be reduced when the reward for participating in the study is transferred as a donation for a charity organization. However, the money donation solution might be unattractive for some respondents. When selecting incentives, researchers need to make sure that the form of the reward is suitable for an online transfer (for examples of such rewards, see Bauermeister et al., 2012; Bengtsson et al., 2012; Lachowsky et al., 2016; Strömdahl et al., 2015).

A Web-based version of the RDS builds on the strengths of online surveys and the RDS method. Potentially the Web-based RDS enables the reaching of large populations in a relatively short time, since the recruitment does not require a physical passing of the coupon (instead, it is passed via the Internet) and interview completion occurs without the need to physically go to a specific location (Tyldum & Johnston, 2014; Wejnert & Heckathorn, 2008). Thus, the Web-based RDS does not pose geographical limits on a study, unlike traditional RDS studies (Bengtsson et al., 2012). Perhaps even more importantly with respect to migration research, the selection of research sites is made by the respondents themselves who choose further study participants from their networks, participants who reside in various places (Salamońska & Czeranowska, 2018). Therefore, the Web-based RDS reduces the financial resources required to carry out a study in terms of interview venue rent, interviewers’ remuneration, and questionnaire printing costs (all relevant for the face-to-face version of the RDS). The online interview mode also may be natural to migrants who navigate the online world in their daily lives to stay in touch with their family and friends who live in other countries.

Among the weaknesses of the Web-based RDS, as opposed to the face-to-face RDS, the former assumes a certain level of digital competences among the target population and Internet access, which may introduce a possible underrepresentation bias (Wejnert & Heckathorn, 2008) with respect to groups such as poor or older migrants. Another weak point of the Web-based RDS is generally understood as the limited control researchers have over the research process. Since the Web-based RDS recruitment process progresses quickly online, they may not be able to react in a timely manner if oversampling of specific sub-groups occurs. As in face-to-face RDS surveys, such potential biases are difficult to identify if they do not take an extreme form (e.g., only men being recruited to a sample). This situation may be explained by the fact that the RDS method usually is employed when official statistics and adequate sample frames are unavailable. Importantly, Web-based RDS researchers have virtually no control over who participates in an interview (Wejnert & Heckathorn, 2008) or over the quality of respondent answers. Moreover, an interviewer is not available to explain the logic of further recruitments to the study or the transfer of e-coupons. At the same time, the risks of duplicated responses and of persons from outside the target population filling in the questionnaires (overusing the survey to reap the prizes) is higher with the Web-based RDS than with other online surveys, since respondents can earn more money by filling out more Web-based RDS questionnaires. Also, in the case of targeting a worldwide population, a research team may find it challenging to design an incentive system that could operate equally efficiently in various countries, a situation in which the same reward will have a different purchasing power, depending on the country (Salamońska & Czeranowska, 2018).

Nevertheless, researchers can attempt to track these misuses of Web-based RDS. For example, researchers can restrict participants to only one questionnaire from any one IP, although this strategy would not block people from repeatedly participating in questionnaires by using various electronic devices. Adding internal checks in a questionnaire, with an aim to detect inconsistencies, would be an option for identifying respondents who do not belong to the studied group.

The Web-based RDS was developed and tested across various studies on “hidden populations,” but, to our knowledge to date, Web-based RDS studies on migrants have not been done. Observations regarding the efficacy of sampling with the Web-based RDS method are mixed and depend on the character of the target population. It can be argued that in the case of groups that have a comparatively strong affiliation to a given community, the Web-based RDS method has been relatively effective, for example, in studies of men who have sex with men living in Vietnam (Bengtsson et al., 2012) or marijuana users in Oregon (Crawford, 2014), and American youth (Bauermeister et al., 2012). However, in other Web-based RDS surveys, researchers have frequently struggled with a low propensity of respondents to recruit their peers and with the problem of short referral chains (e.g., Lachowsky et al., 2016; Strömdahl et al., 2015; Truong et al., 2013). It is clear that methodological research is still needed regarding this domain.

3 Web-Based RDS Survey of Polish Multiple Migrants: Research Design and Overview of the Sample

3.1 Survey Design and Implementation

A Web-based RDS survey on Polish multiple migrants was carried out in 2018 by the Centre of Migration Research, University of Warsaw in a project entitled ‘In search of a theory of multiple migration. A quantitative and qualitative study of Polish migrants after 1989’ (MULTIMIG).Footnote 2 The project was designed to study the migration trajectories of Polish multiple migrants via a mixed methods design, including a Web-based RDS survey and a qualitative panel study.

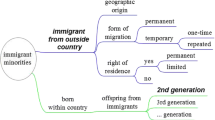

The Web-based RDS target population was defined as adults who were born in Poland and residing abroad at the time of the survey and who had lived for at least 3 months in each of at least two countries other than Poland. No limits were imposed on the country of residence, i.e., the research covered Polish multiple migrants worldwide. The research team also decided to make this definition inclusive of Poles who migrated at different stages of their life courses (also including those who migrated as children) and in different historical periods. Return migrants were not part of the target population.

The data on multiple migrants are scarce, but, for example, according to results of a survey of Polish migrants by the National Bank of Poland in 2016, around 11% of all Polish migrants in four European countries were multiple migrants (with percentages varying by country; see Jancewicz & Salamońska, 2020). Thus, multiple migrants constitute a small fraction of the overall population of Polish emigrants. Multiple migrants also are a hidden and presumably highly geographically dispersed population, which poses additional challenges. They may be quite mobile and yet maintain connections to Poland and other international context(s) in which they have lived. Needless to say, the project design lacked a sampling frame for this group. In other words, for some countries, we had some sample frames that we could use for Polish migrants, but none were available for Polish multiple migrants specifically.

Designing the survey as a Web-based RDS seemed to respond well to the afore-mentioned challenges related to the sampling of this particular target population. However, this assessment would hold only if the two RDS assumptions were met with respect to the existence of the specific virtual network of Polish multiple migrants and the sense of belonging to the group (as required by RDS methodology). Overall, the implementation of the Web-based RDS was supposed to be its methodological test in this research field.

An external market research company specializing in online surveys implemented the Web-based RDS. Our research team had access to a platform that enabled the tracking of the recruitment chains in real time so as to control the recruitment process. We designed the questionnaire in Polish, so knowledge of the Polish language was an additional target group screening criterion, although not explicitly. The questionnaire consisted of the following sections: migrant trajectories, professional trajectories, life course events, social relations, and identity. It also featured RDS-related questions that aimed to assess the size of respondents’ networks of other multiple migrants. Overall, the research topic—tracing the migratory trajectories of multiple migrants and their correlates—required detailed and diversified information from respondents. We designed the questionnaire to take up to 30 min to complete, based on a successful example of an online survey of Latvian emigrants (see Mierina, 2019). We assumed that this length of questionnaire would not increase the number of survey dropouts because of the engaging topic. Additionally, we relied on the expertise of the market research company implementing the survey, which considered the length of our questionnaire as acceptable for an online survey.

We aimed to reach 500 respondents with our survey. At the beginning of the study, our research team identified a small number of potential seeds (four recruited in July 2018) based on the personal networks of researchers and social and professional networking sites. We sent a personalized questionnaire link to these initial seeds. One of the last questionnaire screens included a request for help to recruit three additional respondents to take part in the study. Once the respondents agreed to recruit others (by marking the adequate answer in the questionnaire), we provided them with specific links to the questionnaires and instructed them that they could send these links to up to three other adult Polish multiple migrants living outside of Poland. The provided information included explanations that links were personalized so that they could be used only once and by one person each. The screen with invitation links included information about the reward for recruiting further respondents to the study. It also reminded the participants of the definition of the target population. In hindsight, these explanations did not adequately stress the outstanding importance of the referral system to the study’s success.

For completing an interview, each respondent received PLN40 (equaling to around EUR10). With respect to each successful recruitment of another respondent (a completed interview), a respondent would earn an additional PLN20. So each respondent could earn a maximum of PLN100 (around EUR25). Respondents also could choose PayPal transfer as an incentive form (although this required them to submit personal data when they completed an interview), a charity donation (a reward transfer to one of three charities working with persons with disabilities, animals or older persons), or no prize at all.

We started the fieldwork on July 15th 2018, and it proceeded until December 13th 2018, a period of 5 months in total, which was much longer than expected. A pilot survey that preceded the fieldwork was carried out between May 29th 2018 and June 14th 2018. It involved recruitment of two seeds who could recruit as many respondents as possible for the study. This pilot study was set up to test the questionnaire and also the Web-based RDS recruitment component. Only one of the pilot seeds recruited one respondent for the study, which resulted in three interviews collected at the pilot stage. As a consequence of this small pilot study, we amended the questionnaire, and carefully checked the procedure of passing links for technical problems.

3.2 Sample Overview

We closed the online survey after 515 respondents had replied. During the data cleaning process, we discovered that 35 migrants—although having declared at least two migration experiences in two or more countries at the screening stage—pointed to repeated migration experiences in one country only in the migration trajectories section of the questionnaire. These migrants were excluded from the overview of the sample presented below (i.e., the final sample of Polish multiple migrants was 480 respondents).

The Polish multiple migrants who participated in the Web-based RDS survey mostly had experiences of living in two different countries outside of Poland (55%), whereas a further 28% had lived in three countries and 10% had lived in four countries. Only 6% of our respondents’ trajectories involved living in five or more countries. The countries in which the multiple migrants lived at the time of the interview were predominantly European Union member states. The UK, Germany, Czechia, Spain, Australia, Denmark, Norway, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and the US were the top 10 countries in which the multiple migrants resided (in descending order). The top countries, the UK and Germany, hosted about 9% of the sample each. In the case of Switzerland, the Netherlands, and the US, the sample percentage was around 3% each. As regards the motivations for leaving Poland, the respondents indicated work (40%), family reasons (35%), and simply a wish to live in a new country (35%). Also, some declared mixed motivations for moving.

The vast majority of multiple migrants who participated in the survey were women (75%). The respondents also were relatively young, with a mean age of 34, and the majority was between 25 and 34 years old. The respondents also were highly educated, with over 75% completing a third level education (obtained in Poland or abroad). Most (80%) were in a relationship (either registered or not), and about half had children. About 70% worked in the destination country (this proportion was even higher for men), 15% were caretakers for home and family (these percentages were higher for women), and about 7% were students. Overall, the study enabled reaching quite a heterogeneous sample, with the majority holding high levels of human capital.

4 Effectiveness of Recruitment in the Web-Based RDS

4.1 Overview of the Recruitment Process

We assessed the effectiveness of the recruitment for this Web-based RDS survey on Polish multiple migrants on the basis of the whole obtained sample, i.e., 515 questionnaires,Footnote 3 which enabled the tracking of the dynamics of the data collection. This number refers to the completed interviews only. We did not include incomplete interviews in the database because they, by and large, involved situations in which the respondents did not pass a screener—they did not satisfy the definition of the target group. Overall, while the planned number of questionnaires (500) was achieved, the number of respondents who qualified as seeds (regarding the RDS methodology) amounted to 395 persons, i.e., the vast majority (79%) of the sample. One third of all respondents refused outright to recruit anybody, either for a lack of adequate persons in their network or due to other reasons.Footnote 4

Only 3% of the sample was recruited during the fourth or later wave (at least four persons in the chain recruited somebody). All these respondents belonged to one “exceptional” recruitment chain encompassing 22 persons. This chain started from a young man (25 years old) with secondary education residing in Germany who had migration experiences also beyond Europe. Interestingly, this chain consisted of relatively diverse individuals in terms of, for example, their countries of residence (10 different countries, almost all European) and age (persons born between 1957 and 1995). These migrants often undertook their first migration for study (40.9% vs. 33.8% in the total sample). However, at the time of the survey, they were performing jobs that covered almost the whole occupational ladder in the destination countries. What they did have in common was that, except for one person, they selected a PayPal transfer as the remuneration for an interview. Nevertheless, it would be difficult to identify one clear distinctive feature of the persons who belonged to this single “super-chain,” and the group also was too small for carrying out a meaningful statistical analysis. However, it is worth noting that these 22 interviews were collected over 1 month (from November 5th until December 8th), so at a relatively slow pace.

Overall, one sixth of the obtained overall sample was recruited within the first wave (i.e., by seeds invited to participate in the survey by researchers), 3% in the second wave, and only 1% in the third wave (see Table 4.1). Consequently, for the majority of seeds invited to the study by researchers (82% or 325 seeds),Footnote 5 no recruitment chains were formed, and the chains we did obtain were very short. Thus, this recruitment was not satisfactory at all, given the precondition of the RDS method that to obtain a frequency equilibrium of a sample, recruitment chains should be “long enough” (Heckathorn, 1997). So, even if we treat this precondition in a flexible manner, the recruitment process still did not meet the precondition of the RDS method, since the majority of the sample was recruited by researchers.

It became clear during the fieldwork that the recruitment process based on the RDS method was not effective enough to reach a sample of an adequate size. During the first 3 months of fieldwork, the number of collected questionnaires barely exceeded 10 per month. This was a period when only a limited number of seeds (10 seeds) was recruited, as demanded by the RDS methodology, which were expected to induce long recruitment chains. When at the end of the third month (October 13th) only 32 questionnaires had been collected, the research team changed the strategy by introducing a more intensive recruitment of respondents-seeds. At this stage, the research team still assumed that inducing a more intensive recruitment of respondents was possible and that some of those numerous respondents-seeds would initiate recruitment chains. However, we need to stress that the decision about increasing the recruitment of respondents was an initial step towards relaxing the rigid methodological assumptions of the RDS method. We placed the invitations to participate in the study on more than 120 Facebook groups. Persons interested in participating had to contact a researcher to acquire a personalized link to the questionnaire. This move visibly enhanced the collection of interviews. During the following month of fieldwork, we collected almost 90 questionnaires, i.e., 2.8 questionnaires per day. However, the recruitment driven by the survey participants still was not satisfactory, since the vast majority of the seeds did not recruit anyone.

Therefore, we introduced another modification to the fieldwork—we substantially shortened the questionnaire. The research team saw this change as a methodological test that took into consideration the recommendation of the survey-methods literature to use shorter questionnaires in a web-mode survey (e.g., Hoerger, 2013). We reduced the number of questions from 139 to 91. These cuts included the deletion of questions about exact dates (month and year) of migration moves. According to comments made by respondents, these questions were posing particular difficulties, since they demanded a detailed recollection of mobility trajectories.

We introduced the shorter version of the questionnaire on November 22nd and boosted the collection of data. Until the end of the fieldwork on December 13th, the average speed of data collection was 14.8 questionnaires per day. Among the 311 questionnaires collected during the last 3 weeks of fieldwork, 53 were the longer versions of the questionnaire; they were still circulating on the Internet because the research team decided not to interrupt the potential recruitment process. Overall, the total number of questionnaires in the longer and shorter versions were 257 and 258, respectively. Table 4.2 provides a more detailed description of the three methodological phases of the project.Footnote 6

It is challenging to assess the influence of the shortening of the questionnaire on the speed of data collection. First, respondents could fill in the questionnaire in stages and return to it as many times as they wanted. Consequently, the measurement of the time devoted to the completion of the questionnaire was problematic (the total time between the start and end of filling in the questionnaire). However, the differences between the median duration of time to answer the two versions of the questionnaires (long and short) were visible: 37 min for the longer version and 23 min for the shorter one (the latter was closer to the recommended length in the literature for an online questionnaire). Second, it is difficult to disentangle the effect of the intensity of the recruitment on Facebook groups and other channels carried out by researchers and the external market research company. As portrayed on Fig. 4.1, this active recruitment was crucial in sha** the pace of data collection. Peaks in the numbers of filled-in questionnaires correlated first of all with the timing of the invitation placements on the Internet (Czeranowska, 2019). Over 60% of respondents declared that they found information about the study on the Internet (55% referred directly to Facebook). The maximum daily number of completed long questionnaires was 17, whereas for short questionnaires, it was 34, which suggests that the shortening of the questionnaires had an impact on the readiness of target group members to participate in the study.

Reducing the length of the questionnaire did not impact the effectiveness of the follow-up recruitment by respondents (the key precondition of the RDS method). The overwhelming majority of the respondents who filled in the shorter version of the questionnaire were seeds (84%), and none were recruited during the fourth or later waves, whereas those recruited within the second or third waves constituted only 2% of the analyzed subsample. Moreover, among the one third of respondents who refused to recruit anybody (did not mark an adequate answer in the questionnaire; see Sect. 3.1), the short and long versions of the questionnaires were evenly distributed (50:50). Thus, the factors that restrained the recruitment by respondents did not relate strongly to the length of the questionnaire. Overall, in our study of multiple migrants, the intensification of the seeds’ recruitment and the shortening of the questionnaire produced an increase in data collection speed, although these changes did not stimulate the recruitment by respondents.

4.2 Potential Barriers for the Effective Recruitment

The effectiveness of follow-up recruitment is conditioned by two main factors—the capability to recruit new respondents and the motivation to do so. The former is directly linked to the character of the definition of the target group, which should be clear to the respondents when recruiting others. Furthermore, the criteria should be clear enough to make it simple for them to identify, in their social networks, persons who can be invited to participate in the study. It can be argued that the definition of the multiple migrant employed in the study is rather straightforward: Poles who spent at least 3 months in at least two destination countries. However, determining whether respondents were always aware of all their friends’ migrations and migration durations is less obvious. Possibly, respondents had to check with their acquaintances about the details of their mobility before inviting them to the study. Additionally, instead of checking these details with their friends, respondents may have chosen not to invite anybody, which could have created a barrier to the speed and effectiveness of the recruitment.

Consequently, respondents could have either under- or over-estimated the number of their friends who could be invited to participate in the study. At the same time, a sufficiently high number of other members of the target group within the social networks of respondents was an essential precondition for RDS recruitment to be effective (Gille et al., 2015). This requirement was not fully met in the discussed study. Although only 5% of studied migrants did not know any multiple migrants, 11% had not been in contact (as declared by the respondents in the questionnaire) with such persons during 3 months preceding the survey (Fig. 4.2). This fraction of the sample had almost no capability to recruit new respondents. Over half of the sample was in touch with up to three multiple migrants, but for one fourth, it was only one multiple migrant. The respondents who knew more than 10 multiple migrants constituted another fourth of the sample, but only 8% had been in touch with that many members of the target population during the last 3 months preceding the survey. Therefore, most respondents did not have large Polish multiple migrant networks. Moreover, their ties within these networks were rather loose and weak, since they involved only occasional contacts, which may have been a crucial barrier for recruitment using the Web-based RDS survey approach.

The recruitment capabilities of respondents also relate to the means for distributing invitations, which explains the limited territorial coverage of face-to-face RDS surveys (McCreesh et al., 2011). Although territorial boundaries do not exist on the Internet, Web-based recruitment requires efficient technical solutions. For example, at one point in our survey, the transfer of links (from an inviting person to an invitee) was found to be problematic. Apparently, the personalized links to the questionnaires were too long, which sometimes resulted in copy-and-paste mistakes in the invitation emails to respondents’ friends (Czeranowska, 2019). Moreover, the correspondence of the research team with invited seeds indicated that it was not always clear to seed-respondents that they should copy the links from their questionnaires. Some of the seeds thought that they needed to provide their friends’ personal data in the questionnaires, which made them uncomfortable. This anxiety may have caused them to refuse to recruit anybody. Others, especially those filling in questionnaires on mobile phones, lost their links after switching to their email screen. In case of problems with managing links, respondents were helped by the researchers who sent another link. However, this solution was only possible if they asked for help in the first place. It is difficult to assess how many did not ask for help (ibid.).

The eagerness and engagement of respondents to recruit their peers for a study is, besides their capability to do so, an important precondition for successful recruitment in RDS studies. Thus, it is crucial to create a positive atmosphere around a study (Górny & Napierała, 2016) whether it be carried out in a face-to-face or online setting. Creating such an atmosphere is more difficult for researchers doing Internet surveys, since they do not have any, or at most, have very limited personal contacts with their respondents. Such limited contact usually occurs only with those respondents who get in touch due to problems during the completion of their questionnaire.

Consequently, the research topic and the quality of research tools are the main drivers of the study’s image in an online setting. Our study on multiple migrants seemed attractive to our respondents, although the fact-enumeration style of the questionnaire may have been fatiguing for some of them. In particular, recalling all their migration events was burdensome for those with particularly rich migratory histories (Czeranowska, 2019). In addition, some respondents reported as problematic the lack of the possibility to return to some earlier questions (due to technical issues) to correct answers (e.g., about migrations) (ibid.). These findings suggest that, when attempting to reconstruct migration trajectories by survey questionnaires, an option to enable respondents to correct their earlier answers is a necessity.

The afore-mentioned issues indicate that the questionnaire design can negatively influence the recruitment rate. This finding supports the general rule that Internet surveys need to be simple and engaging, which is even more important with respect to Web-based RDS studies. In this setting, overly demanding questionnaires might not only be a factor that causes them to drop out at some point, but also poses a crucial barrier to respondent recruitment. To put it more clearly, even the respondents who complete a survey might be reluctant to invite their peers to participate if they experienced the survey process as burdensome. Nevertheless, we want to stress that shortening the questionnaire and removing potentially problematic questions in the third phase of the field period did not have a positive effect on the recruitment process by respondents. Only the speed of the seeds’ recruitment increased.

Finally, the incentives used to increase the readiness of respondents to recruit their peers constitute a core element of the method, but their management is always a challenge in RDS studies, particularly as carried out with Web-based surveys. Thus, while money constitutes the most neutral type of incentive, its transfer usually violates the anonymity of respondents in some way. Most research institutes and companies are not allowed to pay money without a signed receipt. With respect to the Internet, the possibility of securing the anonymity of respondents when remunerating them is even more limited, which was the case in this study. Less than half of the respondents (49%) chose to receive a PayPal transfers (which required them to share their personal data with the research company), and 44% decided to donate their renumeration to a charity organization. In fact, respondents valued having the latter option, which is an important methodological observation from the study. At the same time, some respondents expressed their anxiety, in messages to the researchers, about sharing personal data with the research company. It is difficult to evaluate how much this anxiety discouraged some of them from inviting additional participants. Furthermore, regarding the PayPal transfers, some respondents declared (in messages sent to the researchers) that they would not invite their friends to the study until they received a PayPal transfer for the questionnaire they filled-in themselves. Such attitudes may have impeded (time lost waiting for payment) or even restrained (after some time passed, respondents may have forgotten or lost interest in the recruitment) the recruitment of new respondents.

5 Discussion: Challenges to Overcome and Outlook for the Future Use of the Web-Based RDS in Migration Studies and Beyond

The methodological considerations stemming from our study on Polish multiple migrants worldwide using a Web-based RDS strategy relate to the usefulness of online studies in general and the RDS method in particular. On the one hand, the study found that devoting enough time and effort to advertising a survey on the Internet can lead to the collection of a satisfactory number of questionnaires with multiple migrants. On the other hand, inducing the further recruitment of participants by respondents is a challenge when doing Web-based RDS surveys in general (e.g., Lachowsky et al., 2016; Strömdahl et al., 2015; Truong et al., 2013), and, according to our methodological observations, with multiple migrants in particular.

We found that the identified barriers to chain-referral recruitment are of two main types: those linked to RDS assumptions and those related to fieldwork design. The first category refers to the relatively small density of migrants’ networks with other Polish multiple migrants. It also relates to the fact that multiple migrants apparently may not consider themselves a distinct group, i.e., they do not identify themselves with other multiple migrants in terms of a salient social identity. However, the latter is only our supposition because we did not examine group identity in our Web-based RDS survey. This issue could be researched more in-depth in the ongoing MULTIMIG project (in which Web-based RDS was only one of the components), i.e., in a qualitative panel on multiple migrants. Nevertheless, respondents were not necessarily able to identify Poles who had experiences with multiple migration to other destination countries. It seems that Polish multiple migrants do not form a particular social network, but rather seem to be dispersed across various migrant networks (i.e., they are not necessarily directly linked with each other). In other words, although the features of the Web-based RDS method appear to address some challenges related to the sampling of multiple migrants very well, the definition of this migrant group does not fully fit the assumptions of the RDS method in that the respondents were not able to easily identify other members of the target group. An obstacle of a similar kind also has been reported in a study of the early integration patterns of recent migrants (including Poles) in several countries (Platt et al., 2015) in which the RDS recruitment was ineffective due to the limited (direct) connectedness between recent migrants and the fact that the seeds did not refer further respondents—recent migrants—from within their networks.

Barriers to RDS recruitment that stem from the design of the implemented online survey of Polish multiple migrants include a not very effective scheme of distribution of personalized questionnaire links for invitees, the format of the questionnaire (length and the fact-enumeration questions), and last but not least, a reduction of anonymity with respect to PayPal transfers. Moreover, our results suggest that the value of the implemented incentives was of little importance to the recruitment dynamics. The purchasing power of the incentive reward was different depending on in which country the respondents were based. In addition, almost half of the respondents chose the charity donation or no remuneration at all for participating in the survey, which suggests that they had non-financial motivations. Consequently, the dual incentive system, which is integral to recruitment with the RDS method, may have been inefficient in the case of our survey respondents. This tentative finding is in line with the observation that highly-skilled migrants (most of the multiple migrants in our sample) are less likely to participate in RDS surveys because the incentives are relatively unattractive to them, and thus they are not interested in participating and recruiting new participants (Górny, 2017).

Our study of multiple migrants is a useful contribution to ongoing methodological debates in migration studies and beyond. A prerequisite of the RDS method is the recruitment of new participants by respondents themselves, and this is also the main challenge we identified with respect to Web-based RDS surveys. In this regard, our most appealing and straightforward conclusions relate to the limitations of the research design, which can be reduced by intensive testing of the research tool (thus obtaining a relatively short and user-friendly questionnaire), and even more importantly, ensuring smooth operation of the e-coupons transfer. However, we would argue that a more attractive questionnaire format is not always the solution for convincing people to participate in a study, and more importantly, to invite new persons to participate in it. Simply put, not all topics are appropriate for the Web-based RDS approach. The more engaging and salient the topic of the questionnaire is for respondents, the higher the chances of a successful implementation of a Web-based RDS survey, i.e., fast and efficient data collection resulting in long referral chains. While this suggestion is not new, with respect to Web-based RDS surveys it is crucial in order to obtain a sample that would go beyond a mere convenience sample. This, in turn, would not allow for the computation of RDS weights that would enable the obtaining of unbiased estimators for a studied population.

With regard to another element of the research design—the e-coupons form and the procedure of their transfer by respondents—further substantive testing is needed. Prospects for a satisfactory implementation of this procedure should be a pivotal criterion in the choice of the implementation mode of the survey and, if necessary, in the selection of a research company capable of conducting a Web-based RDS survey. Such an approach requires securing substantive resources for the pilot stage in the budget of the Web-based RDS survey because this exploratory stage requires the testing of different recruitment scenarios (to procure a variety of potential seeds) and of various technical solutions. Also during the pilot stage, it would be advisable to do cognitive interviews with respondents, which should focus not only on the comprehension and wording of questions, but also on how an e-coupon transfer occurs in the context of the respondents’ social networks. These interviews should address the recruitment challenges the respondents point to, the solutions to overcome them, the attractiveness of incentives, and the motivations for recruitment. Overall, the e-coupons transfer procedure should be simple and self-governed. We also strongly recommend that researchers provide instructions on how to pass on the coupons, and information on the importance of the referral process for the success of the study. An innovative measure to consider might be the usage of short videos to explain to respondents how to pass on the coupons and to stress the importance of their role as persons inviting new respondents. In face-to-face RDS, this is the interviewers’ role, so, in this regard, the face-to-face RDS version is less demanding.

Another Web-based RDS component that requires attention is the form of incentives used. Both their value (not too high and not too low) and form (easily transferable online) can contribute to the success of the study. On the basis of our review of earlier studies (Bengstsson et al., 2012; Truong et al., 2013), it seems that introducing a lottery element in the incentives scheme will have a positive impact on the eagerness of respondents to participate in a study.

Regarding the RDS assumption-related challenges, the target group should be defined in the simplest way possible, share some common affiliation, and have dense reciprocal ties that bind its members. We would claim that these requirements are even more important in the Web-based RDS, since researchers have less influence on the research process than in face-to-face RDS surveys. This claim directly implies that the formative stage, in preparation for an actual study, should not be neglected in the online versions of RDS surveys. If possible, a pre-study should involve mixed methods and mixed mode approaches, i.e., face-to-face interviews, phone interviews, and online surveying that address the topics important to RDS survey success, such as group affiliation, social networks, readiness to pass coupons, attractiveness of incentives, etc.

To conclude, our methodological test of the Web-based RDS online survey on the population of multiple migrants resulted in several important recommendations regarding such studies’ research design, in particular, with respect to the organization of the e-coupon transfer and the incentives form. It also paid attention to the fact that the Web-based RDS survey, although saving some money on fieldwork (e.g., the costs of organizing the research site, salaries of interviewers), requires substantial funding for an exploratory and testing phase. More studies of this kind are needed to cross-check and validate these recommendations in practice. Finally, the experience we gained during the study led to two important general observations. First, the implementation of established field research methods in a virtual environment provides for new opportunities, but also comes with added challenges. Second, it always is necessary to consider carefully whether the chosen study design procures a sufficiently good fit between its inherent methodological requirements and the particular characteristics of the envisioned target group.

Notes

- 1.

This condition enables the passing of the coupon (via connections in the network) from one person to any other randomly chosen person in the network, independently of the seeds’ selection.

- 2.

This project was funded by the National Science Centre, Poland, under a Sonata Bis Grant, 2016–2021 (ID: 2015/18/E/HS4/00497).

- 3.

Since for 13 respondents the recruitment tracking was missing due to technical issues, we excluded these cases from our analysis of the recruitment process.

- 4.

Before receiving the invitation links, respondents were asked if they would agree to recruit somebody to the study.

- 5.

This number might be lower due to problems with the transfers of links in some invitations (up to 50 cases), so the recruitment process might not have been registered appropriately. We discuss this problem in a later part of this section.

- 6.

This third methodological phase of the project was accompanied by an additional mailing to over 300 Polish organisations worldwide. However, this mailing was not very effective due to a number of inactive addresses and the small response rate from these organisations (IQS, 2018).

References

Bauermeister, J. A., Zimmerman, M. A., Johns, M. M., Glowacki, P., Stoddard, S., & Volz, E. (2012). Innovative recruitment using online networks: Lessons learned from an online study of alcohol and other drug use utilizing a web-based, respondent-driven sampling (webRDS) strategy. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 73(5), 834–838.

Bengtsson, L., Lu, X., Nguyen, Q. C., Camitz, M., Le Hoang, N., Nguyen, T. A., Liljeros, F., & Thorson, A. (2012). Implementation of web-based respondent-driven sampling among men who have sex with men in Vietnam. PLoS One, 7(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0049417

Crawford, S. S. (2014). Revisiting the outsiders: Innovative recruitment of a marijuana user network via web-based respondent driven sampling. Social Networking, 3, 19–31.

Czeranowska, O. (2019). Raport z rekrutacji do badania ilościowego w ramach projektu ‘W poszukiwaniu teorii migracji wielokrotnych. Ilościowe i jakościowe badanie polskich migrantów po 1989 roku’. Centre of Migration Research, University of Warsaw, Warsaw (unpublished report).

Gille, K. J., Johnston, L., & Salganik, M. J. (2015). Diagnostics for respondent-driven sampling. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 178(1), 241–269.

Górny, A. (2017). All circular but different: Variation in patterns of Ukraine-to-Poland migration. Population, Space and Place, 23(8), 1–10.

Górny, A., & Napierała, J. (2016). Comparing the effectiveness of respondent-driven sampling and quota sampling in migration research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 19(6), 645–661.

Heckathorn, D. D. (1997). Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems, 44(2), 174–199.

Heckathorn, D. D. (2007). Extensions of respondent-driven sampling: Analyzing continuous variables and controlling for differential recruitment. Sociological Methodology, 37(1), 151–207.

Hoerger, M. (2013). Participant dropout as a function of survey length in internet-mediated university studies: Implications for study design and voluntary participation in psychological research. Cyberpsychology, Behaviour, and Social Networks, 13(6). https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0445

Jancewicz, B., & Salamońska, J. (2020). Migracje wielokrotne w Europie: polscy migranci w Wielkiej Brytanii, Holandii, Irlandii i Niemczech. Studia Migracyjne—Przegląd Polonijny, 2(176), 7–28. https://doi.org/10.4467/25444972SMPP.20.009.12325

Lachowsky, N. J., Lal, A., Forrest, J. I., Card, K. G., Cui, Z., Sereda, P., Rich, A., Raymond, H. F., Roth, E. A., Moore, D. M., & Hogg, R. S. (2016). Including online-recruited seeds: A respondent-driven sample of men who have sex with men. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(3). https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5258

Malekinejad, M., Johnston, L. G., Kendall, C., Kerr, L. R. F. S., Rifkin, M. R., & Rutherford, G. W. (2008). Using respondent-driven sampling methodology for HIV biological and behavioral surveillance in international settings: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior, 12(Suppl), 105–130.

McCreesh, N., Johnston, L. G., Copas, A., Sonnenberg, P., Seeley, J., Hayes, R. J., Frost, S. D. W., & White, R. G. (2011). Evaluation of the role of location and distance in recruitment in respondent-driven sampling. International Journal of Health Geographics, 10, 10–56.

Mierina, I. (2019). An integrated approach to surveying emigrants worldwide. In K. R. Mierina (Ed.), The emigrant communities of Latvia. National identity, transnational belonging, and diaspora politics (pp. 13–34). Springer.

Montealegre, J. R., Johnston, L. G., Murrill, C., & Monterroso, E. (2013). Respondent driven sampling for HIV biological and behavioral surveillance in Latin America and the Caribbean. AIDS and Behaviour, 17, 2313–2340.

Platt, L., Luthra, R., & Frere-Smith, T. (2015). Adapting chain referral methods to sample new migrants: Possibilities and limitations. Demographic Research, 33(24), 665–700.

Salamońska, J., & Czeranowska, O. (2018). How to research multiple migrants? Introducing web-based respondent-driven sampling survey (CMR Working Papers 110/168). Warsaw University, Warsaw.

Schenker, M. B., Castañeda, X., & Rodriguez-Lainz, A. (Eds.). (2014). Migration and health. A research methods handbook. University of California Press.

Strömdahl, S., Lu, X., Bengtsson, L., Liljeros, F., & Thorson, A. (2015). Implementation of web-based respondent-driven sampling among men who have sex with men in Sweden. PLoS One, 10(10). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138599

Tourangeau, R., Edwards, B., & Johnson, T. P. (Eds.). (2014). Hard-to-survey populations. Cambridge University Press.

Truong, H. H. M., Grasso, M., Chen, Y. H., Kellogg, T. A., Robertson, T., Curotto, A., Steward, W. T., & McFarland, W. (2013). Balancing theory and practice in respondent-driven sampling: A case study of innovations developed to overcome recruitment challenges. PLoS One, 8(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0070344

Tyldum, G., & Johnston, L. (Eds.). (2014). Applying respondent driven sampling to migrant populations. Lessons from the field. Palgrave Macmillan.

Volz, E., & Heckathorn, D. D. (2008). Probability based estimation theory for respondent driven sampling. Journal of Official Statistics, 24(1), 79–97.

Wejnert, C., & Heckathorn, D. D. (2008). Web-based network sampling: Efficiency and efficacy of respondent-driven sampling for online research. Sociological Methods & Research, 37(1), 105–134.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Górny, A., Salamońska, J. (2022). Web-Based Respondent-Driven Sampling in Research on Multiple Migrants: Challenges and Opportunities. In: Pötzschke, S., Rinken, S. (eds) Migration Research in a Digitized World. IMISCOE Research Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-01319-5_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-01319-5_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-01318-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-01319-5

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)