Abstract

Trisomy 21, the common chromosomal abnormality leading to Down syndrome, has become an important model for human chromosome nondisjunction. Here we review studies of the 90 % of chromosome 21 nondisjunction errors occurring in the oocyte that lead to trisomy 21 and have further separated these maternal cases by type of nondisjunction error: maternal meiosis I (MI) or maternal meiosis II (MII). Given the mechanistic differences and temporal separation of MI and MII, many have hypothesized that the risk factors for MI and MII nondisjunction errors are different. The ability to classify errors by parental and stage of origin of the meiotic event allows analysis of less heterogeneous etiologic-based groups, providing insight into factors associated with nondisjunction. These studies show that maternal age is a dominant risk factor for both MI and MII nondisjunction and all other investigations of nondisjunction risk factors must be carried out in the context of maternal age. Studies of recombination profiles and environmental factors by type of nondisjunction error and by maternal age have begun to suggest important features of meiosis that may be more or less vulnerable to exposures. Although results are not always consistent between studies, they have begun to provide insight into possible modifiable factors.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Penrose LS. The relative effects of paternal and maternal age in mongolism. J Genet. 1933;27(1):219–24.

Penrose LS. The relative aetological importance of birth order and maternal age in Mongolism. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 1934;115:431–50.

Penrose LS. Observations on the aetiology of mongolism. Lancet. 1954;267(6837):505–9.

Book JA, Fraccaro M, Lindsten J. Cytogenetical observations in mongolism. Acta Paediatr. 1959;48:453–68.

Ford CE, Jones KW, Miller OJ, et al. The chromosomes in a patient showing both mongolism and the Klinefelter syndrome. Lancet. 1959;1(7075):709–10.

Jacobs PA, Baikie AG, Court Brown WM, et al. The somatic chromosomes in mongolism. Lancet. 1959;1(7075):710.

Le Mongolism LJ. Premier exemple d’aberration autosomique humaine. Ann Genet. 1959;1:41–9.

Mutton D, Alberman E, Hook EB. Cytogenetic and epidemiological findings in Down syndrome, England and Wales 1989 to 1993. National Down Syndrome Cytogenetic Register and the Association of Clinical Cytogeneticists. J Med Genet. 1996;33(5):387–94.

Hook EB, Mutton DE, Ide R, et al. The natural history of Down syndrome conceptuses diagnosed prenatally that are not electively terminated. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57(4):875–81.

Hassold TJ, Jacobs PA. Trisomy in man. Annu Rev Genet. 1984;18:69–97.

Muller F, Rebiffe M, Taillandier A, et al. Parental origin of the extra chromosome in prenatally diagnosed fetal trisomy 21. Hum Genet. 2000;106(3):340–4.

Antonarakis SE, Petersen MB, McInnis MG, et al. The meiotic stage of nondisjunction in trisomy 21: determination by using DNA polymorphisms. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;50(3):544–50.

Ballesta F, Queralt R, Gomez D, et al. Parental origin and meiotic stage of non-disjunction in 139 cases of trisomy 21. Ann Genet. 1999;42(1):11–5.

Sherman SL, Freeman SB, Allen EG, et al. Risk factors for nondisjunction of trisomy 21. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;111(3–4):273–80.

Petersen MB, Antonarakis SE, Hassold TJ, et al. Paternal nondisjunction in trisomy 21: excess of male patients. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2(10):1691–5.

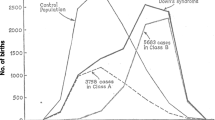

Yoon PW, Freeman SB, Sherman SL, et al. Advanced maternal age and the risk of Down syndrome characterized by the meiotic stage of chromosomal error: a population-based study. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58(3):628–33.

Antonarakis SE, Avramopoulos D, Blouin JL, et al. Mitotic errors in somatic cells cause trisomy 21 in about 4.5 % of cases and are not associated with advanced maternal age. Nat Genet. 1993;3(2):146–50.

Hook EB. Down syndrome rates and relaxed selection at older maternal ages. Am J Hum Genet. 1983;35(6):1307–13.

Sauer MV. The impact of age on reproductive potential: lessons learned from oocyte donation. Maturitas. 1998;30(2):221–5.

Mikkelsen M, Hallberg A, Poulsen H. Maternal and paternal origin of extra chromosome in trisomy 21. Hum Genet. 1976;32:17–21.

Warren AC, Chakravarti A, Wong C, et al. Evidence for reduced recombination on the nondisjoined chromosome 21 in Down syndrome. Science. 1987;237:652–4.

Freeman SB, Allen EG, Oxford-Wright CL, et al. The National Down Syndrome Project: design and implementation. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(1):62–72.

Allen EG, Freeman SB, Druschel C, et al. Maternal age and risk for trisomy 21 assessed by the origin of chromosome nondisjunction: a report from the Atlanta and National Down Syndrome Projects. Hum Genet. 2009;125(1):41–52.

Page SL, Hawley RS. Chromosome choreography: the meiotic ballet. Science. 2003;301(5634):785–9.

Koehler KE, Boulton CL, Collins HE, et al. Spontaneous X chromosome MI and MII nondisjunction events in Drosophila melanogaster oocytes have different recombinational histories. Nat Genet. 1996;14(4):406–14.

Krawchuk MD, Wahls WP. Centromere map** functions for aneuploid meiotic products: analysis of rec8, rec10 and rec11 mutants of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 1999;153(1):49–55.

Moore DP, Miyazaki WY, Tomkiel JE, et al. Double or nothing: a Drosophila mutation affecting meiotic chromosome segregation in both females and males. Genetics. 1994;136(3):953–64.

Rasooly RS, New CM, Zhang P, et al. The lethal(1)TW-6cs mutation of Drosophila melanogaster is a dominant antimorphic allele of nod and is associated with a single base change in the putative ATP-binding domain. Genetics. 1991;129(2):409–22.

Ross LO, Maxfield R, Dawson D. Exchanges are not equally able to enhance meiotic chromosome segregation in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(10):4979–83.

Sears DD, Hegemann JH, Shero JH, et al. Cis-acting determinants affecting centromere function, sister-chromatid cohesion and reciprocal recombination during meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1995;139(3):1159–73.

Zetka MC, Rose AM. Mutant rec-1 eliminates the meiotic pattern of crossing over in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1995;141(4):1339–49.

Lamb NE, Sherman SL, Hassold TJ. Effect of meiotic recombination on the production of aneuploid gametes in humans. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;111(3–4):250–5.

Lamb NE, Feingold E, Savage A, et al. Characterization of susceptible chiasma configurations that increase the risk for maternal nondisjunction of chromosome 21. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6(9):1391–9.

Lamb NE, Freeman SB, Savage-Austin A, et al. Susceptible chiasmate configurations of chromosome 21 predispose to non-disjunction in both maternal meiosis I and meiosis II. Nat Genet. 1996;14(4):400–5.

Oliver TR, Feingold E, Yu K, et al. New insights into human nondisjunction of chromosome 21 in oocytes. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(3):e1000033.

Oliver TR, Tinker SW, Allen EG, et al. Altered patterns of multiple recombinant events are associated with nondisjunction of chromosome 21. Hum Genet. 2012;131(7):1039–46.

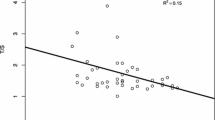

Lamb NE, Yu K, Shaffer J, et al. Association between maternal age and meiotic recombination for trisomy 21. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76(1):91–9.

Ghosh S, Feingold E, Dey SK. Etiology of Down syndrome: evidence for consistent association among altered meiotic recombination, nondisjunction, and maternal age across populations. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A(7):1415–20.

Ghosh S, Hong CS, Feingold E, et al. Epidemiology of Down syndrome: new insight into the multidimensional interactions among genetic and environmental risk factors in the oocyte. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(9):1009–16.

Knowles BA, Hawley RS. Genetic analysis of microtubule motor proteins in Drosophila: a mutation at the ncd locus is a dominant enhancer of nod. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(16):7165–9.

Cheslock PS, Kemp BJ, Boumil RM, et al. The roles of MAD1, MAD2 and MAD3 in meiotic progression and the segregation of nonexchange chromosomes. Nat Genet. 2005;37(7):756–60.

Baker DJ, Jeganathan KB, Cameron JD, et al. BubR1 insufficiency causes early onset of aging-associated phenotypes and infertility in mice. Nat Genet. 2004;36(7):744–9.

Steuerwald N, Cohen J, Herrera RJ, et al. Association between spindle assembly checkpoint expression and maternal age in human oocytes. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001;7(1):49–55.

Orr-Weaver T. Meiotic nondisjunction does the two-step. Nat Genet. 1996;14(4):374–6.

Angell R. Mechanism of chromosome nondisjunction in human oocytes. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1995;393:13–26.

Angell RR, **an J, Keith J, et al. First meiotic division abnormalities in human oocytes: mechanism of trisomy formation. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1994;65(3):194–202.

Hawley RS, Frazier JA, Rasooly R. Separation anxiety: the etiology of nondisjunction in flies and people. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3(9):1521–8.

Koehler KE, Hawley RS, Sherman S, et al. Recombination and nondisjunction in humans and flies. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5 Spec No:1495–504.

Broman KW, Murray JC, Sheffield VC, et al. Comprehensive human genetic maps: individual and sex-specific variation in recombination. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63(3):861–9.

Cheung VG, Burdick JT, Hirschmann D, et al. Polymorphic variation in human meiotic recombination. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80(3):526–30.

Kong A, Gudbjartsson DF, Sainz J, et al. A high-resolution recombination map of the human genome. Nat Genet. 2002;31(3):241–7.

Lynn A, Koehler KE, Judis L, et al. Covariation of synaptonemal complex length and mammalian meiotic exchange rates. Science. 2002;296(5576):2222–5.

Brown AS, Feingold E, Broman KW, et al. Genome-wide variation in recombination in female meiosis: a risk factor for non-disjunction of chromosome 21. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(4):515–23.

Kong A, Thorleifsson G, Stefansson H, et al. Sequence variants in the RNF212 gene associate with genome-wide recombination rate. Science. 2008;319(5868):1398–401.

Chowdhury R, Bois PR, Feingold E, et al. Genetic analysis of variation in human meiotic recombination. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(9):e1000648.

Fledel-Alon A, Leffler EM, Guan Y, et al. Variation in human recombination rates and its genetic determinants. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20321.

Stefansson H, Helgason A, Thorleifsson G, et al. A common inversion under selection in Europeans. Nat Genet. 2005;37(2):129–37.

Kong A, Thorleifsson G, Gudbjartsson DF, et al. Fine-scale recombination rate differences between sexes, populations and individuals. Nature. 2010;467(7319):1099–103.

Berg IL, Neumann R, Lam KW, et al. PRDM9 variation strongly influences recombination hot-spot activity and meiotic instability in humans. Nat Genet. 2010;42(10):859–63.

Baudat F, Buard J, Grey C, et al. PRDM9 is a major determinant of meiotic recombination hotspots in humans and mice. Science. 2010;327(5967):836–40.

Nagaoka SI, Hassold TJ, Hunt PA. Human aneuploidy: mechanisms and new insights into an age-old problem. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(7):493–504.

Pacchierotti F, Eichenlaub-Ritter U. Environmental hazard in the aetiology of somatic and germ cell aneuploidy. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2011;133(2–4):254–68.

Penrose LS. Genetical aspects of mental deficiency. In: Proceedings of the international Copenhagen Congress on the scientific study of mental retardation; 1964. p. 165–72.

Susiarjo M, Hassold TJ, Freeman E, et al. Bisphenol A exposure in utero disrupts early oogenesis in the mouse. PLoS Genet. 2007;3(1):e5.

Eichenlaub-Ritter U, Wieczorek M, Luke S, et al. Age related changes in mitochondrial function and new approaches to study redox regulation in mammalian oocytes in response to age or maturation conditions. Mitochondrion. 2011;11(5):783–96.

Torfs CP, Christianson RE. Socioeconomic effects on the risk of having a recognized pregnancy with Down syndrome. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2003;67(7):522–8.

Christianson RE, Sherman SL, Torfs CP. Maternal meiosis II nondisjunction in trisomy 21 is associated with maternal low socioeconomic status. Genet Med. 2004;6(6):487–94.

Hunter JE, Allen EG, Shin M, Bean LJH, Correa A, Druschel C, Hobbs CA, O’Leary LA, Romitti PA, Royle MH, Torfs CP, Freeman SB, Sherman SL. The association of low socioeconomic status and the risk of having a child with Down syndrome: a report from the National Down Syndrome Project. Genet Med. 2013. Manuscript under submission.

Kline J, Levin B, Shrout P, et al. Maternal smoking and trisomy among spontaneously aborted conceptions. Am J Hum Genet. 1983;35(3):421–31.

Kline J, Levin B, Stein Z, et al. Cigarette smoking and trisomy 21 at amniocentesis. Genet Epidemiol. 1993;10(1):35–42.

Hook EB, Cross PK. Cigarette smoking and Down syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37(6):1216–24.

Hook EB, Cross PK. Maternal cigarette smoking, Down syndrome in live births, and infant race. Am J Hum Genet. 1988;42(3):482–9.

Shiono PH, Klebanoff MA, Berendes HW. Congenital malformations and maternal smoking during pregnancy. Teratology. 1986;34(1):65–71.

Chen CL, Gilbert TJ, Daling JR. Maternal smoking and Down syndrome: the confounding effect of maternal age. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149(5):442–6.

Torfs CP, Christianson RE. Effect of maternal smoking and coffee consumption on the risk of having a recognized Down syndrome pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(12):1185–91.

Cuckle HS, Alberman E, Wald NJ, et al. Maternal smoking habits and Down’s syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 1990;10(9):561–7.

Kallen K. Down’s syndrome and maternal smoking in early pregnancy. Genet Epidemiol. 1997;14(1):77–84.

Yang Q, Sherman SL, Hassold TJ, et al. Risk factors for trisomy 21: maternal cigarette smoking and oral contraceptive use in a population-based case–control study. Genet Med. 1999;1(3):80–8.

Bernstein BE, Meissner A, Lander ES. The mammalian epigenome. Cell. 2007;128(4):669–81.

Gonzalez-Barrios R, Soto-Reyes E, Herrera LA. Assembling pieces of the centromere epigenetics puzzle. Epigenetics. 2012;7(1):3–13.

Xu GL, Bestor TH, Bourc’his D, et al. Chromosome instability and immunodeficiency syndrome caused by mutations in a DNA methyltransferase gene. Nature. 1999;402(6758):187–91.

Hansen RS, Wijmenga C, Luo P, et al. The DNMT3B DNA methyltransferase gene is mutated in the ICF immunodeficiency syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(25):14412–7.

Chouery E, Abou-Ghoch J, Corbani S, et al. A novel deletion in ZBTB24 in a Lebanese family with immunodeficiency, centromeric instability, and facial anomalies syndrome type 2. Clin Genet. 2012;82(5):489–93.

de Greef JC, Wang J, Balog J, et al. Mutations in ZBTB24 are associated with immunodeficiency, centromeric instability, and facial anomalies syndrome type 2. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(6):796–804.

James SJ, Pogribna M, Pogribny IP, et al. Abnormal folate metabolism and mutation in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene may be maternal risk factors for Down syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70(4):495–501.

Coppede F. The complex relationship between folate/homocysteine metabolism and risk of Down syndrome. Mutat Res. 2009;682(1):54–70.

Coppede F, Bosco P, Tannorella P, Romano C, Antonucci I, Stuppia L, et al. DNMT3B promoter polymorphisms and maternal risk of birth of a child with Down syndrome. Hum Reprod. (Oxford, England). 2013;28(2):545–50.

Brandalize AP, Bandinelli E, Dos Santos PA, et al. Maternal gene polymorphisms involved in folate metabolism as risk factors for Down syndrome offspring in Southern Brazil. Dis Markers. 2010;29(2):95–101.

Fintelman-Rodrigues N, Correa JC, Santos JM, et al. Investigation of CBS, MTR, RFC-1 and TC polymorphisms as maternal risk factors for Down syndrome. Dis Markers. 2009;26(4):155–61.

Biselli JM, Zampieri BL, Goloni-Bertollo EM, et al. Genetic polymorphisms modulate the folate metabolism of Brazilian individuals with Down syndrome. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(10):9277–84.

Wang SS, Feng L, Qiao FY, Lv JJ. Functional variant in methionine synthase reductase decreases the risk of Down syndrome in China. The journal of obstetrics and gynaecology research. 2013;39(2):511–5.

Boduroglu K, Alanay Y, Koldan B, et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase enzyme polymorphisms as maternal risk for Down syndrome among Turkish women. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;127(1):5–10.

Chango A, Fillon-Emery N, Mircher C, et al. No association between common polymorphisms in genes of folate and homocysteine metabolism and the risk of Down’s syndrome among French mothers. Br J Nutr. 2005;94(2):166–9.

Kokotas H, Grigoriadou M, Mikkelsen M, et al. Investigating the impact of the Down syndrome related common MTHFR 677C>T polymorphism in the Danish population. Dis Markers. 2009;27(6):279–85.

Mendes CC, Biselli JM, Zampieri BL, et al. 19-base pair deletion polymorphism of the dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) gene: maternal risk of Down syndrome and folate metabolism. Sao Paulo Med J. 2010;128(4):215–8.

Neagos D, Cretu R, Tutulan-Cunita A, et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase (MTHFD) enzyme polymorphism as a maternal risk factor for trisomy 21: a clinical study. J Med Life. 2010;3(4):454–7.

CDC. Recommendations for the use of folic acid to reduce the number of cases of spina bifida and other neural tube defects. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1992;41(RR-14):1–7.

DHHS/PHS. Food standards: amendment of the standards of identity for enriched cereal-grain products to require the addition of folic acid: final rule (21 CFR Parts 136, 137 and 139). Fed Regist. 1996;61:8781–97.

DHHS/PHS. Food additives permitted for direct addition to food for human consumption: folic acid (folacin): final rule (21CFR Part 172). Fed Regist. 1996;61:8797–807.

Ray JG, Meier C, Vermeulen MJ, et al. Prevalence of trisomy 21 following folic acid food fortification. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;120A(3):309–13.

Collins JS, Olson RL, DuPont BR, et al. Prevalence of aneuploidies in South Carolina in the 1990s. Gen Med. 2002;4(3):131–5.

Canfield MA, Collins JS, Botto LD, et al. Changes in the birth prevalence of selected birth defects after grain fortification with folic acid in the United States: findings from a multi-state population-based study. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2005;73(10):679–89.

Simmons CJ, Mosley BS, Fulton-Bond CA, et al. Birth defects in Arkansas: is folic acid fortification making a difference? Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2004;70(9):559–64.

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. Births: final data for 2002. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2003;52(10).

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. Births: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2007;56(6).

Czeizel AE, Puho E. Maternal use of nutritional supplements during the first month of pregnancy and decreased risk of Down’s syndrome: case–control study. Nutrition. 2005;21(6):698–704; discussion 74.

Hollis N, Allen EG, Oliver TR, et al. Preconception folic acid supplementation and risk for chromosome 21 nondisjunction: a report from the National Down Syndrome Project. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161(3):438–44.

Warburton D. Biological aging and the etiology of aneuploidy. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;111(3–4):266–72.

Ghosh S, Feingold E, Chakraborty S, et al. Telomere length is associated with types of chromosome 21 nondisjunction: a new insight into the maternal age effect on Down syndrome birth. Hum Genet. 2010;127(4):403–9.

Hassold T, Chiu D. Maternal age-specific rates of numerical chromosome abnormalities with special reference to trisomy. Hum Genet. 1985;70(1):11–7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sherman, S.L., Allen, E.G., Bean, L.J.H. (2013). Maternal Age and Oocyte Aneuploidy: Lessons Learned from Trisomy 21. In: Schlegel, P., Fauser, B., Carrell, D., Racowsky, C. (eds) Biennial Review of Infertility. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7187-5_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7187-5_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-7186-8

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-7187-5

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)