Abstract

This paper constructs a six-variable VAR model (including NASDAQ returns, TSE returns, NT/USD returns, net foreign purchases, net domestic investment companies (dic) purchases, and net registered trading firms (rtf) purchases) to examine: (i) the interaction among three types of institutional investors, particularly to test whether net foreign purchases lead net domestic purchases by dic and rtf (the so-called demonstration effect); (ii) whether net institutional purchases lead market returns or vice versa; and (iii) whether the corresponding lead-lag relationship is positive or negative? The results of unrestricted VAR, structural VAR, and multivariate threshold autoregression models show that net foreign purchases lead net purchases by domestic institutions and the relation between them is not always unidirectional. In certain regimes, depending on whether previous day’s TSE returns are negative or previous day’s NASDAQ returns are positive, we find ample evidence of a feedback relation between net foreign purchases and net domestic institutional purchases. The evidence also supports a strong positive-feedback trading by institutional investors in the TSE. In addition, it is found that net dic purchases negatively lead market returns in Period 4. The MVTAR results indicate that net foreign purchases lead market returns when previous day’s NASDAQ returns are positive and have a positive influence on returns.

Readers are well advised to refer to chapter appendix for detailed discussion of the unrestricted VAR model, the structural VAR model, and the threshold VAR analysis.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

This is because foreign institutions may well have better research teams and buy stocks according to the fundamentals such as the firm’s future profitability. In contrast, local institutions and individual investors usually choose stocks based on insider information or what the newspapers write about. However, if stocks bought by foreign investors have a better performance than that of local institutions and individual investors, the latter tend to buy the stocks bought by successful foreign investors the previous day. Hence this gives rise to the so-called “demonstration effect.” Such a concept is similar to the “herding” which Lakonishok et al. (1992) referred to as correlated trading across institutional investors. Nonetheless, their definition is close to the contemporaneous correlation rather than the lead-lag relation under study, and as such this leads to the demonstration effect which we documented.

- 2.

Froot et al. (2001) also use daily data, but they examine the behavior of capital flows across countries. In addition, our models and approaches used in the estimation differ drastically from theirs.

- 3.

Lakonishok et al. (1992) refer to the positive-feedback trading or trend chasing as buying winners and selling losers and the negative feedback trading or contrarian as buying losers and selling winners. Cai and Zheng (2002) point out that feedback trading occurs when lagged returns act as the common signal that the investors follow.

- 4.

Karolyi (2002) reaches such a conclusion because there is little evidence of any impact of foreign net purchases on future Nikkei returns or currency returns.

- 5.

The data began on December 13, 1995, since the inception of the TEJ.

- 6.

The main purpose of this paper is to improve our understanding on the interaction among institutional investors and the relationship between institutional trading and stock returns. The following discussion will therefore focus on these two issues.

- 7.

- 8.

Recall that both the positive-feedback and negative-feedback trading are associated with the sign of market returns on the previous trading day.

- 9.

Here, we assume that net purchases by institutions are only affected by market returns on the previous trading day.

- 10.

For more details see Tsay (1998).

- 11.

A previous study by Sadorsky (1999) also splits data into two regimes based on the sign of the variable to discuss whether variables used would change their behaviors under different regimes.

- 12.

To economize space, only relevant impulse responses are presented here; the remaining are available upon request.

Fig. 17.4 Selected impulse responses to innovations up to ten periods in the MVTAR models. (a) r t−1 < 0, (b) r t−1 ≥ 0. Notes: See also Fig. 17.2

References

Brennan, M., & Cao, H. (1997). International portfolio investment flows. Journal of Finance, 52, 1851–1880.

Cai, F., & Zheng, L. (2002). Institutional trading and stock returns (Working paper). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Business School.

Choe, H., Kho, B. C., & Stulz, R. (1999). Do foreign investors destabilize stock markets? The Korean experience in 1997. Journal of Financial Economics, 54, 227–264.

Froot, K. A., O’Connell, P. G. J., & Seasholes, M. S. (2001). The portfolio flows of international investors. Journal of Financial Economics, 59, 151–193.

Griffin, J. M., Harris, J. H., & Topaloglu, S. (2003). The dynamics of institutional and individual trading. Journal of Finance, 58, 2285–2320.

Grinblatt, M., & Keloharju, M. (2000). The investment behavior and performance of various investor-types: A study of Finland’s unique data set. Journal of Financial Economics, 55, 43–67.

Hamao, Y., & Mei, J. (2001). Living with the “enemy”: An analysis of foreign investment in the Japanese equity market. Journal of International Money and Finance, 20, 715–735.

Huang, C.-H., & Hsu, Y. Y. (1999). The impact of foreign investors on the Taiwan stock exchange. Taipei Bank Monthly, 29(4), 58–77.

Kamesaka, A., Nofsinger, J. R., & Kawakita, H. (2003). Investment patterns and performance of investor groups in Japan. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 11, 1–22.

Karolyi, G. A. (2002). Did the Asian financial crisis scare foreign investors out of Japan? Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 10, 411–442.

Lakonishok, J., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1992). The impact of institutional trading on stock price. Journal of Financial Economics, 32, 23–44.

Lee, T. S., & Oh, Y. L. (1995). Foreign investment, stock market volatility and macro variables. Fundamental Financial Institutions, 31, 45–47 (in Chinese).

Lee, Y.-T., Lin, J. C., & Liu, Y. J. (1999). Trading patterns of big versus small players in an emerging market: An empirical analysis. Journal of Banking and Finance, 23, 701–725.

Nofsinger, J. R., & Sias, W. (1999). Herding and feedback trading by institutional and individual investors. Journal of Finance, 54, 2263–2295.

Sadorsky, P. (1999). Oil price shocks and stock market activity. Energy Economics, 21, 449–469.

Sias, R. W., & Starks, L. T. (1997). Return autocorrelation and institutional investors. Journal of Financial Economics, 46, 103–131.

Tsay, R. S. (1998). Testing and modeling multivariate threshold models. Journal of American Statistical Association, 93(443), 1188–1202.

Wang, L.-R., & Shen, C. H. (1999). Do foreign investments affect foreign exchange and stock markets? – The case of Taiwan. Applied Economics, 31(11), 1303–1314.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

17.1.1 The Unrestricted VAR Model

The prices of many Taiwanese electronics securities are affected by the NASDAQ returns and hence foreign portfolio inflows may induce fluctuations of exchange rate. To investigate interactions emanated from the three types of institutional investors and the relationship between institutional trading activity and stock returns in Taiwan, we employ a six-variable VAR model using the NASDAQ returns (nasr t ), currency returns (Δe t ), TSE returns (r t ), net foreign purchases (qfiibs t ), net dic purchases (dicbs t ), and net rtf purchases (rtfbs t ) as the underlying variables. We attempt to answer the issues pertaining to (i) the interaction among trading activities of the three types of institutions and (ii) the relationship between stock returns and institutional trading. First, we propose a six-variable unrestricted VAR model shown below:

Where ϕ ij (L) is the polynomial lag of the jth variable in the ith equation. To investigate the lead-lag relation among three types of institutional investors, we need to test the hypothesis that each off-diagonal element in the sub-matrix \( \left[\begin{array}{l}{\phi}_{44}(L)\kern0.5em {\phi}_{45}(L)\kern0.5em {\phi}_{46}(L)\\ {}{\phi}_{54}(L)\kern0.5em {\phi}_{55}(L)\kern0.5em {\phi}_{56}(L)\\ {}{\phi}_{64}(L)\kern0.5em {\phi}_{65}(L)\kern0.5em {\phi}_{66}(L)\end{array}\right] \) is zero.

On the other hand, to determine whether the TSE returns of the previous day lead net purchases by the three types of institutional investors, we test the hypothesis that each polynomial lag in the vector \( {\left[\begin{array}{ccc}\hfill {\phi}_{43}(L)\hfill & \hfill {\phi}_{53}(L)\hfill & \hfill {\phi}_{63}(L)\hfill \end{array}\right]}^{\prime } \) is zero. Conversely, if we want to determine whether previous day’s net purchases by institutional investors lead current market returns, we test the hypothesis that each element in the vector [ϕ 34(L)ϕ 35(L)ϕ 36(L)] is zero. Before applying the VAR model, an appropriate lag structure needs to be specified. A 3-day lag is selected based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC). Table 17.5 presents the lead-lag relation among the six time series using block exogeneity tests.

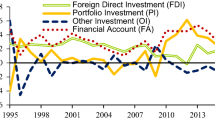

The \( \left[\begin{array}{l}{\phi}_{44}(L)\kern0.5em {\phi}_{45}(L)\kern0.5em {\phi}_{46}(L)\\ {}{\phi}_{54}(L)\kern0.5em {\phi}_{55}(L)\kern0.5em {\phi}_{56}(L)\\ {}{\phi}_{64}(L)\kern0.5em {\phi}_{65}(L)\kern0.5em {\phi}_{66}(L)\end{array}\right] \) block represents the potential interaction among three types of institutional investors. The results indicate that net foreign purchases lead net dic purchases and the dynamic relationship between these two variables can be provided by the impulse response function (IRF) in Fig. 17.2a. Clearly, a one-unit standard error shock to net foreign purchases leads to an increase in net dic purchases, but this effect dissipates quickly by Period 2. Figure 17.2b, c indicate a feedback relation between net purchases by qfii and rtf. A one-unit standard error shock to net foreign purchases results in a positive response to net rtf purchases over the next two periods, which become negative in Period 3, followed by a positive response again after Period 4. Furthermore, a one-unit standard error shock to net rtf purchases also gives rise to an increase in net foreign purchases, which decays slowly over ten-period horizon.

Figure 17.2d shows that net purchases by dic lead net rtf purchases. A one-unit standard error shock to net dic purchases produces an increase in net rtf purchases in the first three periods and then declines thereafter. Overall, these impulse responses suggest that previous day’s net foreign purchases exert a noticeable impact on net rtf purchases, while previous day’s net rtf purchases also has an impact on net foreign purchases. It implies that not only do foreign capital flows affect the trading activity of domestic institutional investors but also the relation is not unidirectional. To be specific, there is a feedback relation between net rtf purchases and net foreign purchases.

As for the effect of the three types of institutional trading activity on stock returns in the TSE, Table 17.5 reveals that net dic purchases on previous day lead the TSE returns. We can also see in Fig. 17.2e that after Period 3, net dic purchases exert a negative (and thus destabilizing) effect on market returns, while the other two institutional investors do not have such an effect over the sample period. Examining the relationship between market returns and trading activity of the three types of institutional investors, we find that either the net foreign purchases or the net dic purchases on previous trading day are affected by the previous day’s TSE returns. Moreover, the IRFs in Fig. 17.2f, g also reveal a significant positive relation between TSE returns and net foreign purchases up to four periods and a significant positive relation between TSE returns and net dic purchases for two periods, which becomes negative after Period 3. In other words, foreign investors in the TSE engage in positive-feedback trading, while those of the dic tend to change their strategy and adopt negative-feedback trading after Period 3.

Table 17.5 indicates that previous day’s NASDAQ returns significantly affect both current TSE returns and net purchases by the three types of institutional investors. The impulse response in Fig. 17.2h–k also confirms that previous day’s NASDAQ returns are positively related to both current returns and net purchases by these institutional investors, with the exception that a negative relation between net dic purchases and previous day’s NASDAQ returns is found after Period 4. Such results are much in sync with the expectation since the largest sector that comprises the TSE-weighted stock index is the electronics industry to which many listed companies on NASDAQ have a strong connection. In addition, although previous day’s net qfii and dic purchases also lead the NASDAQ returns, we find that no significant relation exists except for Period 4 with a significantly negative relation between them (Figs. 17.1 and 17.2).

The liberalization of Taiwan’s stock market has ushered in significant amount of short-term inflows and outflows of foreign capital, which have induced fluctuations in the exchange rate. As is seen from Table 17.5, the TSE returns lead currency returns and it appears that the initial significant effect of stock returns on currency returns is negative for the first three periods and then turns to be significantly positive thereafter (Fig. 17.2n). Given that foreign investors are positive-feedback traders, the capital inflows is expected to grow in order to increase their stakes in TSE securities when stock prices rise. Consequently, NT/USD is expected to appreciate.

17.1.2 The Structural VAR Model

The unrestricted VAR model does not consider the effect of current returns on net purchases by institutions. The prior study by Griffin et al. (2003) includes current returns in the institutional imbalance equation and finds a strong contemporaneous positive relation between institutional trading and stock returns. Therefore, to further examine the relationship between institutional trading and stock returns, we introduce the current TSE returns (r t ) in the net purchases equations of the three types of institutional investors and reestimate the VAR model before conducting the corresponding block exogeneity tests. Table 17.6 presents the estimation results.

As indicated in the last row of Table 17.6, we find evidence of a strong contemporaneous correlation between current returns and net institutional purchases, which confirms the finding by the previous research. As shown in Table 17.5, we find no evidence that past returns lead net rtf purchases when the unrestricted VAR model is used. When the contemporaneous impact of stock returns on net institutional purchases is considered, we find that past returns also lead net rtf purchases as well as net purchases by qfii and dic when the structural VAR model is used (Table 17.6). In other words, net purchases by the three types of institutions are affected by past stock returns as was evidenced by previous studies. The corresponding impulse response relations are presented in Fig. 17.3.

Comparing the impulse response relations in Figs. 17.2 and 17.3, it is clear that when the impact of current returns on net institutional purchases is considered, a one-unit standard error shock from r t does not produce a positive impulse response in institutional trading until Period 2. The responses of foreign investors are rather distinct from those of domestic institutional investors after Period 3. In general, a sustained positive response from foreign investors is observed, while a negative response is witnessed for dic and sometimes, an insignificant response for rtf manifests itself after Period 3.

17.1.3 The Threshold VAR Analysis

We pool all the data together when estimating either the unrestricted or restricted VAR model; however, the trading activity of institutional investors may depend on whether stock prices rise or fall. A small economy like Taiwan also depends to a large degree on the sign of NASDAQ index returns. Consequently, to investigate institutional trading under distinct regimes based on market returns, we use the multivariate threshold autoregression (MVTAR) model proposed by Tsay (1998) to test the relevant hypotheses. Let y t = [nasr t , Δe t , r t , qfiibs t , dicbs t , rtfbs t ]′ be a 6 × 1 vector and the MVTAR model can be described as

where E(ε) = 0, E(εε′) = Σ, and I(⋅) is an index function, which equals 1 if the relation in the bracket holds. It equals zero otherwise. z t−d is the threshold variable with a delay (lag) d.

In order to explore whether institutional trading activity would change during different domestic and foreign market return scenarios, the potential threshold variables used are r t−1 and nasr t−1. Before estimating Eq. 2, we need to test for possible potential nonlinearity (threshold effect) in this equation. Tsay (1998) suggests using the arranged regression concept to construct the C(d) statistic to test the hypothesis H o :ϕ i,1 = ϕ i,2, i = 0, …p. If H 0 can be rejected, it implies that there exists the nonlinearity in data with z t−d as the threshold variable. Tsay (1998) proves that C(d) is asymptotically a chi-square random variable with k(pk + 1) degrees of freedom, where p is the lag length of the VAR model and k is the number of endogenous variables y t . Table 17.7 presents the estimation results of the C(d) statistic.

As shown in Table 17.7, the null hypothesis H 0 is rejected using either past returns on the TSE or NASDAQ, suggesting that our data exhibit nonlinear threshold effect. Theoretically, one needs to rearrange the regression based on the size of the threshold variable z t−d before applying a grid search method to find the optimal threshold value c *. Nonetheless, our goal is to know whether the institutional trading behavior depends on the sign of market returns, as such the threshold is set to zero in a rather arbitrary way. Table 17.8 lists the results of block exogeneity tests for the lead-lag relation in the r t−1 < 0 and r t−1 ≥ 0 regimes, respectively.

The interaction among institutional investors is depicted in Table 17.8: Current net purchases by foreign investors affect that by domestic institutions when previous day’s TSE returns are negative. Note that no such relation is evidenced when previous day’s TSE returns are positive. A feedback relation between rtf and qfii is observed when r t−1 is positive or negative. However, dic is found to lead rtf only when r t−1 is positive. Such results reveal different institutional trading strategies under distinct return regimes. The demonstration effect – previous day’s net foreign purchases have on domestic institutions using the unrestricted VAR model – seems to surface only when previous day’s market returns are negative. Therefore, it may produce misleading results if we fail to consider the sign of previous returns.

The impulse responses in Fig. 17.4 illustrate that the responses of dic and rtf from the qfii shock are quite similar to the ones in Fig. 17.2f, g. As for the impact of previous day’s market returns on current net purchases by institutions, it can be shown via the MVTAR model that market returns lead net purchases by qfii and dic when previous day’s market returns are negative, which is consistent with the finding using the one-regime VAR model. When previous day’s market returns are positive, market returns lead net purchases by the dic only. Obviously, returns have more influence on net institutional purchases when previous day’s returns were negative. In addition, we find that net dic purchases on the previous day may affect current returns when the one-regime VAR model is used. Actually, the MVTAR analysis reveals that such a relation emerges only when previous day’s market returns are positive. The impulse responses depicted in Fig. 17.4 (Panel B) demonstrate that a one-unit standard error shock to net dic purchases produces an increase in market returns in Period 2, and then they turns to be negative after Period 4, a result similar to those using the one-regime VAR model.

To further investigate whether the interaction among institutions and the relationship between institutional trading and stock returns are affected by the sign of previous day’s NASDAQ index return, nasr t−1 is used as the threshold variable. That is, block Granger causality tests are performed by splitting our data into two regimes based on the sign of the variable nasr t−1. Table 17.9 reports the results.

The results indicate that net qfii purchases lead that of two domestic institutional investors regardless of the sign of previous day’s NASDAQ returns. Moreover, when nasr t−1 < 0, net rtf purchases lead net qfii purchases, which is in line with that using the one-regime VAR model. However, when nasr t−1 ≥ 0, the net purchases by either dic or rtf lead net qfii purchases, and net qfii purchases lead net purchases by either dic or rtf. In other words, we find strong evidence of a feedback relation between net foreign purchases and two domestic net purchases when previous day’s NASDAQ returns are positive. The results pertaining to the impact of previous day’s returns on institutional trading parallel those using the unrestricted VAR model: Previous day’s returns have an impact on the net purchases by qfii and dic, but not on net purchases by rtf regardless of the sign of previous day’s NASDAQ returns. As for the impact of net institutional purchases on previous day’s stock returns, only net dic purchases still lead stock returns when nasr t−1 < 0, as was the case in the one-regime model. However, we find that net qfii purchases also lead stock returns when nasr t−1 ≥ 0.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this entry

Cite this entry

Huang, BN., Hung, K., Lee, CH., Yang, C.W. (2015). Dynamic Interactions Between Institutional Investors and the Taiwan Stock Returns: One-Regime and Threshold VAR Models. In: Lee, CF., Lee, J. (eds) Handbook of Financial Econometrics and Statistics. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7750-1_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7750-1_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-7749-5

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-7750-1

eBook Packages: Business and Economics