Abstract

The relationship between terrorism and journalism has been described as symbiotic or parasitic, meaning that especially terrorists gain from news media publicity. This chapter describes how journalists cover terrorist attacks and terrorist groups. It focuses on common research designs (e.g., quantitative, qualitative, and computational approaches). Moreover, it explains how variables such as sourcing, labeling of acts and actors of political violence, radicalization narratives, or emotionalization are often studied in terrorism research and journalism studies.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Terrorism research has seen an increase in scholarly debate and empirical studies since the 1970s, with an abrupt rise after the September 11, 2001 attacks (Jones 2007; Kocks et al. 2011; Miller and Mills 2009). Terrorism studies is an interdisciplinary research field, with most studies stemming from disciplines such as political studies, psychology, and sociology and only a few from journalism or media studies (Jones 2007; Silke 2004). The relationship between journalism and terrorism has been described as symbiotic (Elter 2008; Miller 1982; Surette et al. 2009; Wilkinson 1987), meaning that the two are mutually dependent. Terrorists rely on the media to make their acts and atrocities public and reach a wider audience; journalists cannot refuse to report about a terrorist act because of their function as news providers. Moreover, terrorism is a newsworthy topic, so coverage will lead to higher economic revenue. However, some researchers have described the relationship as parasitic rather than symbiotic (Schaffert 1992; Schultz 2017) because terrorists “force” the media to report. This can be regarded as an act of exploitation in which the parasite (the terrorists) (mis)uses the functions of the media that are obliged to report important events to the public.

Common research questions in content analyses include a focus on which terrorist attacks make it into the headlines (Sui et al. 2017; Weimann and Brosius 1991), coverage, labeling, and framing of violent groups (Dunn et al. 2005; Hellmueller et al. 2022); Zhang and Hellmüller 2016), and—to a lesser extent—coverage of individual terrorists (Knight 2007). Studies examining news values, for instance, find that attacks in Western countries with a high number of fatalities and attacks by Muslim perpetrators are considered more newsworthy by the Western media (Hase 2021; Kearns et al. 2019). Studies also analyze radicalization narratives in the media (Auer et al. 2019; Nacos 2005) and radicalizing narratives in terrorist propaganda (Ingram 2017; Mahood and Rane 2017) with the latter strand of research illustrating that terrorists focus on identity building via in- and outgroup dichotomy, crisis reinforcement, and depiction of violence and military success (Colas 2017; Lorenzo-Dus et al. 2018; Rothenberger et al. 2018). Research also includes audience reactions to attacks on social media (Fischer-Preßler et al. 2019). Single case studies prevail, but we find comparative angles across these lines of research (e.g., through comparisons by group, ideology, or motivation of the attack) (Decker and Rainey 1982) or by media from various countries (Peralta Ruiz 2000). Content analyses across media channels (e.g., TV and print coverage), however, are not common.

2 Common Research Designs and Combinations of Methods

Frequent study designs include quantitative and qualitative content analyses of legacy and non-legacy media and of political statements and speeches, with the formal research object being texts and, to a lesser extent, images or videos (Gerstenfeld 2003; Beuthner et al. 2003). We also find surveys and experiments on the understanding and effects of terrorism or terrorism coverage from the recipients’ perspective (Huff and Kertzer 2018; Shoshani and Slone 2008), while surveys concerning the communicators (be it journalists, politicians, or terrorists) are missing. Guided interviews reconstructing working routines have sometimes been used (Konow-Lund and Olsson 2016), but observations of journalists’ working routines in times of terror are largely missing.

The main method of scientific data collection and analysis used in research on terrorism and media is content analysis, mostly of articles in Western print media. A review of the state of research revealed a strong focus on content analyses of print and television coverage of specific terrorist acts (event centered) and few analyses of background information during attacks (context centered) (Rothenberger 2022). Discourse analyses and longitudinal comparative studies are less frequent. Traditional manual content analyses are the most common, but computational methods, such as automated content analysis or network analysis, are increasingly used, such as to uncover journalistic sourcing (Rauchfleisch et al. 2017) or automatically analyze topics of social media discussions on terrorism (Fischer-Preßler et al. 2019). Some studies also combine media data with extra-media data such as databases recording terrorist attacks and their characteristics (Hase 2021; Hellmueller et al. 2022). Knelangen (2009) examined the pros and cons of qualitative versus quantitative terrorism research. He concluded that it is ultimately the research question that decides which method or combination of methods is appropriate.

Concerning the research object, there is a lack of content analyses of radio programs and of ethnographic studies of terrorists’ daily lives in the respective areas, including observations of their media use (Ross 2007). Although Gerstenfeld’s (2003) content analysis of 157 extremist websites concluded that the internet is a particularly powerful and effective instrument for extremists to reach an international audience, recruit members, network with other groups, and enable a high level of image control, content analyses of traditional mass media are still most common.

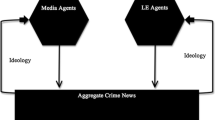

If we follow the order determined by the course of communication from the attack to the audience, we have studies dealing with terrorists’ utterances on the internet (An et al. 2018), media coverage (with word choice playing an important role during the journalistic production phase) (Badr 2017; Glück 2007), and the effects on recipients, including emotional reception (Haußecker 2013).

One always has to take into account that normative prescriptions of how to cover terrorism may change over time according to editorial guidelines (e.g., insofar as a TV channel speaks of “martyrs” or not or whether perpetrators are named and visualized). Beermann (2004), Cohen-Almagor (2005) and Schmid (1992) notice many differences in editorial policies and coherence of using the label “terrorism”. According to Beermann (2004), the Reuters news agency, for example, does not refer to specific events as “terrorism” since the 1960s.

3 Main Constructs

While studies deal with different research objects (e.g., terrorist attacks, terrorist groups, single terrorists, or radicalization) and use different methods of analysis, spanning from computational to discourse analysis, six variables are measured repeatedly:

-

1.

Key issue: Many studies analyze the key issue in an article (i.e., what aspect is emphasized when it comes to terrorism). Studies thereby differentiate between descriptions of a terrorist attack and its course, the severity and consequences of an attack, political reactions in the form of official statements by politicians, military reactions in the form of the “war against terror,” and how to counter terrorism as key issues (Guzek 2019; Mogensen et al. 2002; Zhang and Hellmüller 2016).

-

2.

Sources: Many studies analyze frequent sources used in terrorism coverage. They find that government officials/politicians are predominantly sourced, but so are other media outlets/news agencies, security/police, witnesses/ordinary people, or terrorists themselves (Matthews 2013; Venger 2019; Zhang and Hellmüller 2016). As social media allows for quick updates, the use of Twitter, for example, normalized over time (Bennett 2016).

-

3.

Labeling of groups and events: Content analyses also examine labels of violent events and groups (i.e., what attacks and perpetrators are called in news coverage). Labeling is an important aspect of coverage, as different labels for groups (e.g., “terrorists” vs. “freedom fighters”) and incidents (e.g., “terrorist attack” vs. “crime”) attach dissimilar normative associations and motives (Bhatia 2005). Military action against a perpetrator, for example, might be more easily supported if that person is explicitly labeled a “terrorist” (Baele et al. 2019), as the term implies “that a given action is illegitimate” (Steuter 1990, p. 261) and thus legitimizes military reactions. This might also be why news media generally tend to be cautious about attaching that label (Nagar 2010).

Studies operationalizing such labeling differentiate between labels for events (e.g., “attack,” “explosion,” “seizure”) and groups (e.g., “rebel,” “terrorist,” “murderer”) and find that these vary with incident and perpetrator characteristics and by who is providing the description (Elmasry and el-Nawawy 2020; Lavie-Dinur et al. 2018; Hase 2021; Simmons and Lowry 1990). With the rise of religious terrorism, many studies find that outlets have created new labels connecting Islam and terrorism (e.g., “radical Islam” or “Islamic terrorists”) (Mahony 2010).

-

4.

Radicalization narratives: News media try to make sense of the radicalization of especially young people by constructing narratives around their turn toward terrorism and attributing certain reasons for that choice. Common media explanations proposed for the radicalization of (mostly male) adolescents are religious fanaticism, being the victim of brainwashing by extremists, or naively joining in search for an adventure (Berbers et al. 2016). Interestingly, studies find these radicalization narratives to be gendered: when the media describes suspected female terrorists, it concentrates more on their physical appearance, sexuality, supposed naivety, and troubling social life (Conway and McInerney 2012; Martini 2018; Nacos 2005).

-

5.

Emotionalization: Emotionalization is another aspect of coverage and can be operationalized as a the inclusion of persons who express or are ascribed emotions in text or images (Gerhards et al. 2011). Unsurprisingly, studies find around half the coverage to be emotionalized (Wolf 2010) and that the dominant emotions are mostly implicit and negative, such as sorrow, fear, and devastation (Gerhards et al. 2011).

-

6.

Visualization: In addition, research shows that visualization (operationalized, for example, as the number of visuals accompanying textual coverage or what is shown on these) plays an important role for memorial purposes, personification, and calls for solidarity in the wake of an attack. Studies on visualization thereby differentiate between the visuals shown (e.g., if buildings, memorial gatherings, victims, perpetrators, or flags are displayed in news or social media content) (Berkowitz 2017; Beuthner et al. 2003; Kim 2012). Interestingly, violence—an inherent part of terrorism—is more likely to be illustrated in the form of destroyed buildings than mutilations/wounded people. Legacy media mostly show dead people as covered up (Jirschitzka et al. 2010; Linder 2011)—in contrast to propaganda content, where violent images often are part of the terrorists’ message (Winkler et al. 2019).

4 Research Desiderata

This overview clarified that the operationalization of terrorism-related variables remains a challenge. Terrorism as a label that signifies an asymmetric relation always includes a component of “power” that manifests in media content. As only few international studies outside of the US and “the West” exist, it is usually the US/Western perspective on terrorism that we find in empirical studies (this is to some extent also due to language barriers and thus the international visibility of research). Further, analyses often deal with spectacular, singular attacks in Western countries instead of including a broader view (e.g., by including longitudinal coverage of certain groups or radicalization narratives). The selection of studies in this article accordingly reflects this bias.

Content analyses of web content face the difficulty of co** with a plethora of texts and visuals, from politicians, journalists, citizen journalists, extremists, terrorists, etc. Computer-assisted methods of data collection (e.g., scra**) and data analysis (e.g., automated content analyses) are required to deal with such “big data” but are—as of yet—rarely applied. Additionally, it is not only the commonly known web that is of interest to terrorism researchers: “terrorists’/extremists’ internet usage is still under-researched because of the lack of systematic Dark Web content collection and analysis methodologies” (Quin et al., 2006, p. 4). Another problem of content analyses in the field of terrorism studies is that many miss a close link to a coherent theoretical framework guiding the research. Beck and Quandt (2011) complain about many of the content analyses after the September 11 attacks that were published under great pressure of topicality and that leave it unclear to what extent journalism and communication studies can provide a theoretical understanding of the phenomenon.

Relevant Variables in DOCA—Database of Variables for Content Analysis

Key issue: https://doi.org/10.34778/2u

Sources: https://doi.org/10.34778/2w

Labeling of groups and events: https://doi.org/10.34778/2v

References

An, Y., Mejía, N. A., Arizi, A., Villalobos, M. M, & Rothenberger, L. (2018). Perpetrators’ strategic communication: Framing and identity building on ethno-nationalist terrorists’ websites. Communications, 43(2), 133–171.

Auer, M., Sutcliffe, J., & Lee, M. (2019). Framing the ‘White Widow’: Using intersectionality to uncover complex representations of female terrorism in news media. Media, War & Conflict, 12(3), 281–298.

Badr, H. (2017). Framing von Terrorismus im Nahostkonflikt: Eine Analyse deutscher und ägyptischer Printmedien [Framing terrorism in the mideast conflict: An analysis of German and Egypt print media]. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Baele, S. J., Sterck, O. C., Slingeneyer, T., & Lits, G. P. (2019). What does the “terrorist” label really do? Measuring and explaining the effects of the “terrorist” and “Islamist” categories. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 42(5), 520–540.

Beck, K., & Quandt, T. (2011). Terror als Kommunikation? Was Handlungstheorie, Rational Choice-, Netzwerk- und Systemtheorie aus kommunikationswissenschaftlicher Sicht zur Erklärung leisten [Terror as communication? The contribution of action theory, rational choice, network, and systems theory to an explanation from a communication studies perspective]. In T. Quandt & B. Scheufele (Eds.), Ebenen der Kommunikation [Levels of communication] (pp. 85–110).

Beermann, T. (2004). Der Begriff „Terrorismus“ in deutschen Printmedien. Eine empirische Studie [The term “terrorism” in German print media. An empirical study]. Münster: LIT-Verlag.

Bennett, D. (2016). Sourcing the BBC’s live online coverage of terror attacks. Digital Journalism, 4(7), 861–874.

Berbers, A., Joris, W., Boesman, J., d’Haenens, L., Koeman, J., & Van Gorp, B. (2016). The news framing of the ‘Syria fighters’ in Flanders and the Netherlands: Victims or terrorists? Ethnicities, 16(6), 798–818.

Berkowitz, D. (2017). Solidarity through the visual: Healing images in the Brussels terrorism attacks. Mass Communication and Society, 20(6), 740–762.

Beuthner, M., Buttler, J., Fröhlich, S., Neverla, I., & Weichert, S. A. (2003). Bilder des Terrors – Terror der Bilder? Krisenberichterstattung am und nach dem 11. September [Images of terror – terror of images? Crisis coverage on and after September 11]. Köln: Herbert von Halem Verlag.

Bhatia, M. V. (2005). Fighting words: Naming terrorists, bandits, rebels and other violent actors. Third World Quarterly, 26(1), 5–22.

Cohen-Almagor, R. (2005). Media coverage of acts of terrorism: Troubling episodes and suggested guidelines. Canadian Journal of Communication, 30, 383–409.

Colas, B. (2017). What does Dabiq do? ISIS hermeneutics and organizational fractures within Dabiq Magazine. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 40(3), 173–190.

Conway, M., & McInerney, L. (2012). What’s love got to do with it? Framing ‘JihadJane’ in the US press. Media, War & Conflict, 5(1), 6–21.

Decker, W., & Rainey, D. (1982, November). Media and terrorism. Toward the development of an instrument to explicate their relationship. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED224060.pdf

Dunn, E. W., Moore, M., & Nosek, B. A. (2005). The war of the words: How linguistic differences in reporting shape perceptions of terrorism. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 5(1), 67–86.

Elmasry, M. H., & el-Nawawy, M. (2020). Can a non-Muslim mass shooter be a “terrorist”?: A comparative content analysis of the Las Vegas and Orlando shootings. Journalism Practice, 14(7), 63-879.

Elter, A. (2008). Propaganda der Tat. Die RAF und die Medien [Propaganda of the deed. The RAF and the media]. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Ette, M., & Joe, S. (2018). ‘Rival visions of reality’: An analysis of the framing of Boko Haram in Nigerian newspapers and Twitter. Media, War & Conflict, 11(4), 392–406.

Fischer-Preßler, D., Schwemmer, C., & Fischbach, K. (2019). Collective sense-making in times of crisis: Connecting terror management theory with Twitter user reactions to the Berlin terrorist attack. Computers in Human Behavior, 100, 138–151.

Gerhards, J., Schäfer, M., Al-Jabiri, I., & Seifert, J. (2011). Terrorismus im Fernsehen. Formate, Inhalte und Emotionen in westlichen und arabischen Sendern [Terrorism on TV. Formats, contents, and emotions in Western and Arab channels]. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Gerstenfeld, P. B., Grant, D. R., & Chiang, C.-P. (2003). Hate online: A content analysis of extremist internet sites. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 3(1), 29–44.

Glück, C. (2007). ETA und die Medien [ETA and the media]. In S. Glaab (Ed.), Medien und Terrorismus – Auf den Spuren einer symbiotischen Beziehung [Media and Terrorism - illustrating a symbiotic relationship] (pp. 17–30). Berlin: BMV Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag GmbH.

Guzek, D. (2019). Religious motifs within reporting of the 7/7 London bombings in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Poland: A transnational agenda-setting network study. Journalism, 20(10), 1323–1342.

Hase, V. (2021). What is terrorism (according to the news)? How the German press selectively labels political violence as “terrorism”. Journalism. Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/14648849211017003.

Haußecker, N. (2013). Terrorismusberichterstattung in Fernsehnachrichten: Visuelles Framing und emotionale Reaktionen [Terrorism coverage on TV: visual framing and emotional reactions]. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Hellmueller, L., Hase, V., & Lindner, P. (2022). Terrorist Organizations in the News: A Computational Approach to Measure Media Attention Toward Terrorism. Mass Communication and Society, 25(1), 134–157.

Huff, C., & Kertzer, J. D. (2018). How the public defines terrorism. American Journal of Political Science, 62(1), 55–71.

Ingram, H. J. (2017). An analysis of inspire and Dabiq: Lessons from AQAP and Islamic State’s propaganda war. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 40(5), 357–375.

Jirschitzka, J., Haußecker, N., & Frindte, W. (2010). Mediale Konstruktion II: Die Konstruktion des Terrorismus im deutschen Fernsehen – Ergebnisdarstellung und Interpretation. [Media construction II: the construction of terrorism in German TV - results and interpretation]. In W. Frindte & N. Haußecker (Eds.), Inszenierter Terrorismus [Staged terrorism] (pp. 81–119). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Jones, A. (2007). Terrorism studies: Theoretically under-developed? Retrieved from http://www.e-ir.info/2007/12/22/terrorism-studies-theoretically-under-developed/

Kearns, E. M., Betus, A. E., & Lemieux, A. F. (2019). Why do some terrorist attacks receive more media attention than others? Justice Quarterly, 36(6), 985–1022.

Kim, Y. S. (2012). News images of the terrorist attacks: Framing September 11th and its aftermath in the pictures of the year international competition. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 20(3), 158–184.

Knelangen, W. (2009). Terrorismus – Im Zentrum der politischen Debatte, immer noch an den Rändern der Forschung [Terrorism – At the heart of the political debate, on the brink of research]? In H.-J. Lange, H.P. Ohly & J. Reichertz (Eds.), Auf der Suche nach neuer Sicherheit: Fakten, Theorien und Folgen [In search of new security: facts, theories and consequences] (pp. 75–88). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Knight, A. (2007). Jihad and cross-cultural media: Osama bin Laden as reported in the Asian press. Pacific Journalism Review, 13(2), 155–174.

Kocks, A., Harbrich, K., & Spencer, A. (2011). Die Entwicklung der deutschen Terrorismusforschung: Auf dem Weg zu einer ontologischen und epistemologischen Bestandsaufnahme [Development of German terrorism research: inventory-taking of ontologies and epistemologies.] In A. Spencer, A. Kocks & K. Harbrich (Eds.), Terrorismusforschung in Deutschland [Terrorism research in Germany] (pp. 9–21). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Konow-Lund, M., & Olsson, E.-K. (2016). When routines are not enough: Journalists’ crisis management during the 22/7 domestic terror attack in Norway. Journalism Practice, 10(3), 358–372.

Lavie-Dinur, A., Yarchi, M., & Karniel, Y. (2018). The portrayal of lone wolf terror wave in Israel: An unbiased narrative or agenda driven? The Journal of International Communication, 24(2), 196–215.

Linder, B. (2011). Terror in der Medienberichterstattung [Terrorism in media coverage]. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Lorenzo-Dus, N., Kinzel, A., & Walker, L. (2018). Representing the West and “non-believers” in the online jihadist magazines Dabiq and Inspire. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 11(3), 521–536.

Mahony, I. (2010). Diverging frames: A comparison of Indonesian and Australian press portrayals of terrorism and Islamic groups in Indonesia. International Communication Gazette, 72(8), 739–758.

Mahood, S., & Rane, H. (2017). Islamist narratives in ISIS recruitment propaganda. The Journal of International Communication, 23(1), 15–35.

Martini, A. (2018). Making women terrorists into “Jihadi brides”: An analysis of media narratives on women joining ISIS. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 11(3), 458–477.

Matthews, J. (2013). News narratives of terrorism: Assessing source diversity and source use in UK news coverage of alleged Islamist plots. Media, War & Conflict, 6(3), 295–310.

Miller, A. H. (1982). Terrorism, the media and the law. Dobbs Ferry: Transnational Publishers.

Miller, D., & Mills, T. (2009). The terror experts and the mainstream media: The expert nexus and its dominance in the news media. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 2(3), 414–437.

Mogensen, K., Lindsay, L., Perkins, J., & Beardsley, M. (2002). How TV news covered the crisis: The content of CNN, CBS, ABC, NBC and Fox. In B. S. Greenberg (Ed.), Communication and terrorism: Public and media responses to 9/11 (pp. 101–120). Cresskill, N.J: Hampton Press.

Nacos, B. L. (2005). The portrayal of female terrorists in the media: Similar framing patterns in the news coverage of women in politics and in terrorism. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 28(5), 435–451.

Nagar, N. (2010). Who is afraid of the T-word? Labeling terror in the media coverage of political violence before and after 9/11. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 33(6), 533–547.

Peralta Ruiz, V. (2000). Sendero Luminoso y la Prensa, 1980–1994. La violencia política peruana y su representación en los medios [Sendero Luminoso/Shining path in the press, 1980–1994. Peruvian political violence and its representation in the media]. Cuzco: SUR Casa de Estudios del Socialismo.

Quin, J., Reid, E., Lai, G., & Chen, H. (2006). Unraveling international terrorist groups’ exploitation of the web: Technical sophistication, media richness, and web interactivity. In H. Chen, F.-Y. Wang, C. C. Yang, D. Zeng, M. Chau, & K. Chang (Eds.), Intelligence and Security Informatics (pp. 4–15). Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer.

Rauchfleisch, A., Artho, X., Metag, J., Post, S., & Schäfer, M. S. (2017). How journalists verify user-generated content during terrorist crises. Analyzing Twitter communication during the Brussels attacks. Social Media + Society, 3(3), 1–13.

Ross, J. I. (2007). Deconstructing the terrorism news media relationship. Crime, Media, Culture, 3(2), 215–225.

Rothenberger, L. (2022). Terrorismus as communication. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Rothenberger, L., Müller, K., & Elmezeny, A. (2018). The discursive construction of terrorist group identity. Terrorism and Political Violence, 30(3), 428–453.

Schaffert, R. W. (1992). Media coverage and political terrorists. A quantitative analysis. New York: Praeger.

Schmid, A. P. (1992). Editors’ perspectives. In David L. Paletz & Alex P. Schmid (Eds.), Terrorism and the Media (pp. 111–136). Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Schultz, T. (2017). Nichts ist sicher. Herausforderungen in der Berichterstattung über Terrorismus [Nothing is certain. Challenges in terrorism coverage]. In K. N. Renner, T. Schultz, J. Wilke & V. Wolff (Eds.), Journalismus zwischen Autonomie und Nutzwert [Journalism between autonomy and utility] (pp. 99–117). Köln: Herbert von Halem Verlag.

Shoshani, A., & Slone, M. (2008). The drama of media coverage of terrorism: Emotional and attitudinal impact on the audience. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 31(7), 627–640.

Silke, A. (2004). Research on terrorism. Trends, achievements and failures. London: Frank Cass.

Simmons, B. K., & Lowry, D. N. (1990). Terrorists in the news, as reflected in three news magazines, 1980–1988. Journalism Quarterly, 67(4), 692–696.

Steuter, E. (1990). Understanding the media/terrorism relationship: An analysis of ideology and the news in time magazine. Political Communication, 7(4), 257–278.

Sui, M., Dunaway, J., Sobek, D., Abad, A., Goodman, L., & Saha, P. (2017). U.S. news coverage of global terrorist incidents. Mass Communication and Society, 20(6), 895–908.

Surette, R., Hansen, K., & Noble, G. (2009). Measuring media oriented terrorism. Journal of Criminal Justice, 37, 360–370.

Venger, O. (2019). The use of experts in journalistic accounts of media events: A comparative study of the 2005 London Bombings in British, American, and Russian newspapers. Journalism, 20(10), 1343–1359.

Weimann, G., & Brosius, H.-B. (1991). The newsworthiness of international terrorism. Communication Research, 18(3), 333–354.

Wilkinson, P. (1987). Terrorism: An international research agenda? Problems of definition and typology. In P. Wilkinson & A. M. Stewart (Eds.), Contemporary Research on Terrorism (pp. xi–xx). Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press.

Winkler, C., El Damanhoury, K., Dicker, A., & Lemieux, A. F. (2019). Images of death and dying in ISIS media: A comparison of English and Arabic print publications. Media, War & Conflict, 12(3), 248–262.

Wolf, K. (2010). Inszenierungstendenzen der Terrorismusberichterstattung im Fernsehen [Tendencies in staging terrorism coverage on TV]. In W. Frindte & N. Haußecker (Eds.), Inszenierter Terrorismus: Mediale Konstruktionen und individuelle Interpretationen [Staged terrorism: media constructions and individual interpretations] (pp. 232–254). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Zhang, X., & Hellmüller, L. (2016). Transnational media coverage of the ISIS threat: A global perspective? International Journal of Communication, 10, 766–785.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access Dieses Kapitel wird unter der Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de) veröffentlicht, welche die Nutzung, Vervielfältigung, Bearbeitung, Verbreitung und Wiedergabe in jeglichem Medium und Format erlaubt, sofern Sie den/die ursprünglichen Autor(en) und die Quelle ordnungsgemäß nennen, einen Link zur Creative Commons Lizenz beifügen und angeben, ob Änderungen vorgenommen wurden.

Die in diesem Kapitel enthaltenen Bilder und sonstiges Drittmaterial unterliegen ebenfalls der genannten Creative Commons Lizenz, sofern sich aus der Abbildungslegende nichts anderes ergibt. Sofern das betreffende Material nicht unter der genannten Creative Commons Lizenz steht und die betreffende Handlung nicht nach gesetzlichen Vorschriften erlaubt ist, ist für die oben aufgeführten Weiterverwendungen des Materials die Einwilligung des jeweiligen Rechteinhabers einzuholen.

Copyright information

© 2023 Der/die Autor(en)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rothenberger, L., Hase, V. (2023). Content Analysis in the Research Field of Terrorism Coverage. In: Oehmer-Pedrazzi, F., Kessler, S.H., Humprecht, E., Sommer, K., Castro, L. (eds) Standardisierte Inhaltsanalyse in der Kommunikationswissenschaft – Standardized Content Analysis in Communication Research. Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-36179-2_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-36179-2_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer VS, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN: 978-3-658-36178-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-658-36179-2

eBook Packages: Social Science and Law (German Language)