Abstract

Central Asia is highly vulnerable to climate change owing to a set of critical interactions between the region’s socio-economic and environmental contexts. While some of the Central Asian countries are among the states contributing the least to global greenhouse gas emissions, they are already suffering directly from the effects of climate change. This chapter presents an overview of the physical impacts of climate change in Central Asia using the most recent literature, including the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). It identifies climate change-related risks and sectoral vulnerabilities for the region, providing background information to serve as context for the later chapters.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Central Asia’s Climate

Central Asia is one of the most mountainous regions in the world, but has landscapes ranging from grasslands to deserts and woodlands in addition to its high mountains. The mountains of Central Asia consist of two major mountain ranges—the Pamir and the Tien Shan—which are critical to the livelihoods of the local communities. As shown in Fig. 1, the region is influenced by a variety of climates, with the desert and Mediterranean type environments in the south and continental climes everywhere else. The wide range of climates results in a high level of temporal and spatial variability in temperature and precipitation in the region. In most high-elevation areas, where the climate is dry and continental, there are hot summers and cool or cold winters with periodic snowfall. At lower elevations, the climate is mostly semi-arid to arid, with hot summers and mild winters with occasional rain and/or snow.

Map of the different climates in Central Asia according to the Köppen climate classification. Credit: ‘Central Asia map of Köppen climate classification’. Source World Köppen classification (with authors), enhanced, modified and vectorized by Ali Zifan. This figure is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution License (cc-by), license: CC-BY-SA-4.0, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

2 Current and Projected Impacts of Climate Change

In 2021, Working Group I of the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) released its contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report in which they presented the most up-to-date physical understanding of the Earth’s climate system and climate change. Once again, they pointed to the unequivocal human influence on our planet, and our warming of the atmosphere, oceans and land. This new report specifically examines the regional impacts of climate change—or Climate Impact Drivers (CIDs)—on the so-called ‘climate reference regions’. These include ‘West Central Asia’ (WCA), which corresponds to our area of interest. For simplicity, we refer to the WCA region as ‘Central Asia’ in this chapter.

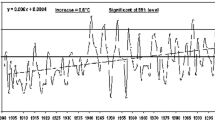

For Central Asia, the IPCC (2021) foresees several key changes in CIDs, including some that are predicted with ‘high confidence’. The IPCC predicts a future increase in mean temperature and extreme heat as well as a decrease in cold spells and frost. They also report that, with the exception of a reduction in frost, these changes have already emerged in the historical period covered by their analysis. This is consistent with several studies (Hu et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2019) showing how Central Asia has been warming faster than the global average over recent decades, with altitudinal variations (Haag et al. 2019) already affecting the region and local populations in multiple ways. These trends are concerning, particularly as the IPCC (2021) also predicts other changes with high confidence, for instance a loss of snow, glaciers and icesheets, declines in which have already been observed in several locations in the Pamir and Tien Shan mountain ranges (Sorg et al. 2012; Barandun et al. 2020). These changes have important implications in terms of water availability, a crucial and contentious resource in Central Asia (Vakulchuk et al. 2022). This issue could be aggravated further since the IPCC predicts—with medium confidence—an increase in aridity, alongside an increase in agricultural and ecological droughts. The combined increase in droughts and heatwaves can produce favorable conditions for wildfires, increasing the potential for burning across Central Asia (IPCC 2021) and the related risk of biodiversity loss (IPBES 2021).

Unlike mean temperature, changes in mean precipitation can be difficult to assess as climate models diverge on the direction and magnitude of the predicted changes (Christensen et al. 2013). The region’s complex topography and lack of climate observations can at least partly explain the heterogeneous results. More recent work, however, is starting to shed light on expected future changes for Central Asia, such as a robust increase in annual mean precipitation, which is expected to be greatest over the Tian Shan mountains and the northern part of the region (Jiang et al. 2020). According to the 2021 IPCC report, the climate models also agree (with high confidence) on an increase in extreme precipitation leading to an increase in pluvial floods and associated landslides (the latter with medium confidence). Other types of flood risk are also expected: Zaginaev et al. (2019) have already observed an increase in glacial lake outburst floods over recent decades in Central Asia owing to its many high-altitude lakes and rapidly melting glaciers.

3 Sectoral Impacts and Vulnerabilities

Climate change has the potential to severely impact the livelihoods of local populations in Central Asia, with simultaneous and interlinked effects on the agriculture, energy, and transport sectors, as well as on public health. This section describes the ways in which the vulnerability of some of the most important sectors in Central Asia could increase in the future as a result of the effects of climate change.

3.1 Crop Production, Livestock and Food Security

In Central Asia, the majority of the population lives in rural areas and is highly dependent on agriculture and irrigation. The impacts of climate change on agriculture are diverse, and may be both positive and negative. Higher carbon dioxide concentrations and warmer temperatures can trigger an increase in crop yields (Orlov et al. 2021), whereas the impacts of extreme events (e.g. droughts, floods or heatwaves) can be devastating. The impacts on livestock should also not be omitted: climate change can affect both the quality of the feed and the health of the animals. The impacts on crops and livestock have obvious implications in terms of food security (see Standal et al., this volume).

3.2 Energy and Water Availability

The energy sector is also highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change as it is largely based on hydropower. Similarly to agriculture, the impacts on this sector can be both positive and negative. On the one hand, for some locations the increase in temperatures can lead to a diminution in the number of days where heating is required, therefore reducing the demand on the energy system. On the other hand, the current melting of glaciers and/or extreme precipitation can lead to floods, damaging infrastructure and leaving communities without electricity. In addition, the disappearance of glaciers, decreases in snow and/or changes to precipitation variability can also make water less available, increasing the pressure on the energy system as water is crucial for generating energy through hydropower. Furthermore, as more water will be needed for irrigation in the future, water use could become a source of tension between the energy and agriculture sectors. Water is already a contentious resource in Central Asia; a decrease in water availability could also exacerbate tensions between nations.

3.3 Health and Air Pollution

The expected increase in extreme temperatures will enhance heat stress for both urban and rural populations. In cities, more frequent and intense heatwaves can affect the health of the population, especially the most vulnerable, e.g. the youngest and the oldest (Meade et al. 2020). For rural populations, an increase in heat stress can affect the health of livestock, as well as impacting the health of the farmers and their ability to work outside (Orlov et al. 2021). Additionally, the impacts of climate change can lead to a decline in food quality via a decrease in nutrients, leading to increasing malnutrition (Myers et al. 2014). The potential increase in wildfires could also lead to an increase in air pollution, which is already a concern in urban areas in this region (UNDP 2021).

3.4 Transportation and Mobility

Transportation is interconnected with many sectors as it encompasses the mobility of people, energy and goods. In Central Asia, the projected effects of climate change (e.g. increase in flooding) can limit road access, limiting transportation or rendering it impossible. These impacts can have severe consequences for the livelihoods of local populations as well as the energy or agriculture sectors (see Blondin, this volume).

4 Conclusion

This chapter has provided an overview of the physical impacts of climate change in Central Asia and shown the increasing threat it represents for this region. According to the most recent literature, including the 2021 IPCC report, multiple changes in Climate Impact Drivers (CIDs) are expected in the future, including changes in mean temperatures and precipitation levels (rain and snow), as well as extreme events such as droughts, heatwaves and floods. The IPCC report also shows that some of these trends have already emerged in the historical period of their analysis. All these changes will increase the vulnerability of local populations via impacts to and across the energy, agriculture and transport sectors, as well as to public health (Vakulchuk et al. 2022). In this context, climate change can generate multiple tensions, including between sectors and between nations. For instance, the agriculture and energy sectors may find themselves fighting over water, an already contested resource in Central Asia, while questions of water scarcity and energy and food security could potentially cause or exacerbate tensions between Central Asian countries.

To better prepare for climate change and to limit its effects, mitigation and adaptation measures appropriate to the context of Central Asia are needed. To this end, more research is needed across the disciplines (Vakulchuk et al. 2022; Vakulchuk and Overland 2021) on, for example, extreme events and their multiple societal and sectoral impacts or on the linkages between gender and climate change. Some of this knowledge is presented in the following chapters of this book, but additional work is necessary to better assess the impacts of climate change in this region. This research will be key to designing the requisite adaptation and mitigation measures for Central Asia.

References

Barandun M, Fiddes J, Scherler M, Mathys T, Saks T, Petrakov D, Hoelzle M (2020) The state and future of the cryosphere in Central Asia. Water Secur 11:100072. ISSN 2468-3124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasec.2020.100072

Christensen JH et al (2013) Climate phenomena and their relevance for future regional climate change. In: Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 1268–1283

Climate Risk Profile (2021) Climate risk profile: Kyrgyz Republic. The World Bank Group and Asian Development Bank. https://www.adb.org/

Haag I, Jones PD, Samimi C (2019) Central Asia’s changing climate how temperature and precipitation have changed across time, space, and altitude. Climate 7(10):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli7100123

Hu Z, Zhang C, Hu Q, Tian H (2014) Temperature changes in Central Asia from 1979 to 2011 based on multiple datasets. J Clim 27:1143–1167

IPBES (2021) Scientific outcome of the IPBES-IPCC workshop on biodiversity and climate change. https://www.ipbes.net/sites/default/files/2021-06/2021_IPCC-IPBES_scientific_outcome_20210612.pdf

IPCC (2021) Climate change 2021: the physical science basis (eds: Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pirani A, Connors S L, Péan C, Berger S, Caud N, Chen Y, Goldfarb L, Gomis MI, Huang M, Leitzell K, Lonnoy E, Matthews JBR, Maycock TK, Waterfield T, Yelekçi O, Yu R, Zhou B). Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (in press)

Jiang J, Zhou T, Chen X, Zhang L (2020) Future changes in precipitation over Central Asia based on CMIP6 projections. Env Res Lett 15:054009

Meade RD, Akerman AP, Notley SR, McGinn R, Poirier P, Gosselin P, Kenny GP (2020) Physiological factors characterizing heat-vulnerable older adults: a narrative review. Environ Int 144:105909. ISSN 0160-4120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105909

Myers SS, Zanobetti A, Kloog I et al (2014) Increasing CO2 threatens human nutrition. Nature 510(7503):139–142. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13179

Orlov A, Daloz AS, Sillmann J et al (2021) Global economic responses to heat stress impacts on worker productivity in crop production. Econ Dis Cli Change 5:367–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-021-00091-6

Sorg A, Bolch T, Stoffel M et al (2012) Climate change impacts on glaciers and runoff in Tien Shan (Central Asia). Nature Clim Change 2:725–731. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1592

UNDP (2021) Tackling air pollution in Europe and Central Asia for improved health and greener future. http://undp.org/

Vakulchuk R, Overland I (2021) Central Asia is a missing link in analyses of critical materials for the global clean energy transition. One Earth 4(12):1678–1692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.11.012

Vakulchuk R, Daloz AS, Overland I, Sagbakken HF, Standal K (2022) A void in Central Asia research: climate change. Cent Asian Surv: 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2022.2059447

Zaginaev V, Petrakov D, Erokhin S, Meleshko A, Stoffel M, Ballesteros-Cánovas JA (2019) Geomorphic control on regional glacier lake outburst flood and debris flow activity over northern Tien Shan. Glob Planet Change 176:50–59. ISSN 0921-8181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2019.03.003; https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921818118306635

Zhang M, Chen Y, Shen Y, Li B (2019) Tracking climate change in Central Asia through temperature and precipitation extremes. J Geogr Sci 29:3–28

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Daloz, A.S. (2023). Climate Change: A Growing Threat for Central Asia. In: Sabyrbekov, R., Overland, I., Vakulchuk, R. (eds) Climate Change in Central Asia. SpringerBriefs in Climate Studies. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29831-8_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29831-8_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-29830-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-29831-8

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)