Abstract

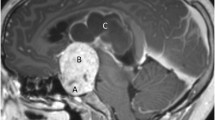

Despite some apparent similarities several differences exist between adult and paediatric craniopharyngiomas starting from the histology. Papillary CPs occur almost exclusively in adults, whereas adamantinomatous CPs can occur in a bimodal age distribution but have been found in any age group. Adamantinomatous CPs tend to be more complicated lesions consisting of large cysts, areas of calcifications and can form strong adhesions to surrounding neurovascular structures. Moreover, children have a unique set of physiological and anatomical factors that can restrict surgical access. They also tend to fair less favourably in long-term outcomes. In this chapter we will discuss these points in an attempt to compare and contrast paediatric and adult craniopharyngiomas.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK. In: Fred T. Bosman ESJ, Lakhani SR, Ohgaki H, editors. WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC; 2007. p. 309.

Sofela AA, et al. Malignant transformation in craniopharyngiomas. Neurosurgery. 2014;75:306.

Nielsen EH, et al. Incidence of craniopharyngioma in Denmark (n = 189) and estimated world incidence of craniopharyngioma in children and adults. J Neuro-Oncol. 2011;104:755.

Zacharia BE, et al. Incidence, treatment and survival of patients with craniopharyngioma in the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program. Neuro-Oncology. 2012;14(8):1070–8.

Dohrmann GJ, Farwell JR. Intracranial neoplasms in children: a comparison of North America, Europe, Africa, and Asia. Dis Nerv Syst. 1976;37(12):696–7.

Haupt R, et al. Epidemiological aspects of craniopharyngioma. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19(Suppl 1):289–93.

Wang L, et al. Primary adult infradiaphragmatic craniopharyngiomas: clinical features, management, and outcomes in one Chinese institution. World Neurosurg. 2014;81(5-6):773–82.

Qi S, et al. Anatomic relations of the arachnoidea around the pituitary stalk: relevance for surgical removal of craniopharyngiomas. Acta Neurochir. 2011;153(4):785–96.

Davis SW, et al. Pituitary gland development and disease: from stem cell to hormone production. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2013;106:1–47.

Prabhu VC, Brown HG. The pathogenesis of craniopharyngiomas. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21(8-9):622–7.

Bao Y, et al. Origin of craniopharyngiomas: implications for growth pattern, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of tumor recurrence. J Neurosurg. 2016;125(1):24–32.

Prieto R, et al. Craniopharyngioma adherence: a reappraisal of the evidence. Neurosurg Rev. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-018-1010-9.

Ciappetta P, Pescatori L. Anatomic dissection of arachnoid membranes encircling the pituitary stalk on fresh, non-formalin-fixed specimens: anatomoradiologic correlations and clinical applications in craniopharyngioma surgery. World Neurosurg. 2017;108:479–90.

Pascual JM, Prieto R, Carrasco R. Infundibulo-tuberal or not strictly intraventricular craniopharyngioma: evidence for a major topographical category. Acta Neurochir. 2011;153(12):2403–25; discussion 2426.

Nielsen EH, et al. Acute presentation of craniopharyngioma in children and adults in a Danish national cohort. Pituitary. 2013;16(4):528–35.

Daubenbuchel AM, et al. Hydrocephalus and hypothalamic involvement in pediatric patients with craniopharyngioma or cysts of Rathke’s pouch: impact on long-term prognosis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172(5):561–9.

Elliott RE, Wisoff JH. Surgical management of giant pediatric craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2010;6(5):403–16.

Schlaffer SM, et al. Rathke’s cleft cyst as origin of a pediatric papillary craniopharyngioma. Front Genet. 2018;9:49.

Borrill R, et al. Papillary craniopharyngioma in a 4-year-old girl with BRAF V600E mutation: a case report and review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2019;35:169.

Apps JR, Martinez-Barbera JP. Molecular pathology of adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma: review and opportunities for practice. Neurosurg Focus. 2016;41(6):E4.

Sekine S, et al. Expression of enamel proteins and LEF1 in adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma: evidence for its odontogenic epithelial differentiation. Histopathology. 2004;45(6):573–9.

Larkin SJ, Ansorge O. Pathology and pathogenesis of craniopharyngiomas. Pituitary. 2013;16(1):9–17.

Schweizer L, et al. BRAF V600E analysis for the differentiation of papillary craniopharyngiomas and Rathke’s cleft cysts. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2015;41(6):733–42.

Brastianos PK, Santagata S. Endocrine tumors: BRAF V600E mutations in papillary craniopharyngioma. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;174(4):R139–44.

Malgulwar PB, et al. Study of beta-catenin and BRAF alterations in adamantinomatous and papillary craniopharyngiomas: mutation analysis with immunohistochemical correlation in 54 cases. J Neuro-Oncol. 2017;133(3):487–95.

Holsken A, et al. Adamantinomatous and papillary craniopharyngiomas are characterized by distinct epigenomic as well as mutational and transcriptomic profiles. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2016;4:20.

Hussain I, et al. Molecular oncogenesis of craniopharyngioma: current and future strategies for the development of targeted therapies. J Neurosurg. 2013;119(1):106–12.

Yoshimoto K, et al. High-resolution melting and immunohistochemical analysis efficiently detects mutually exclusive genetic alterations of adamantinomatous and papillary craniopharyngiomas. Neuropathology. 2018;38(1):3–10.

Gao C, et al. Exon 3 mutations of CTNNB1 drive tumorigenesis: a review. Oncotarget. 2018;9(4):5492–508.

Yang Y. Wnt signaling in development and disease. Cell Biosci. 2012;2(1):14.

Apps JR, et al. Tumour compartment transcriptomics demonstrates the activation of inflammatory and odontogenic programmes in human adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma and identifies the MAPK/ERK pathway as a novel therapeutic target. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;135(5):757–77.

Preda V, et al. The Wnt signalling cascade and the adherens junction complex in craniopharyngioma tumorigenesis. Endocr Pathol. 2015;26(1):1–8.

Burghaus S, et al. A tumor-specific cellular environment at the brain invasion border of adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas. Virchows Arch. 2010;456(3):287–300.

Stache C, et al. Tight junction protein claudin-1 is differentially expressed in craniopharyngioma subtypes and indicates invasive tumor growth. Neuro-Oncology. 2014;16(2):256–64.

Massimi L, et al. Proteomics in pediatric cystic craniopharyngioma. Brain Pathol. 2017;27(3):370–6.

Martelli C, et al. Proteomic characterization of pediatric craniopharyngioma intracystic fluid by LC-MS top-down/bottom-up integrated approaches. Electrophoresis. 2014;35(15):2172–83.

Benveniste EN, Qin H. Type I interferons as anti-inflammatory mediators. Sci STKE. 2007;2007(416):pe70.

Falini B, Martelli MP, Tiacci E. BRAF V600E mutation in hairy cell leukemia: from bench to bedside. Blood. 2016;128(15):1918–27.

Brastianos PK, et al. Dramatic response of BRAF V600E mutant papillary craniopharyngioma to targeted therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(2):djv310.

Himes BT, et al. Recurrent papillary craniopharyngioma with BRAF V600E mutation treated with dabrafenib: case report. J Neurosurg. 2018;130:1299–303.

Jung TY, et al. Adult craniopharyngiomas: surgical results with a special focus on endocrinological outcomes and recurrence according to pituitary stalk preservation. J Neurosurg. 2009;111(3):572–7.

Cheng J, Fan Y, Cen B. Effect of preserving the pituitary stalk during resection of craniopharyngioma in children on the diabetes insipidus and relapse rates and long-term outcomes. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28(6):e591–5.

Li K, et al. Association of pituitary stalk management with endocrine outcomes and recurrence in microsurgery of craniopharyngiomas: a meta-analysis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2015;136:20–4.

Jung TY, et al. Endocrinological outcomes of pediatric craniopharyngiomas with anatomical pituitary stalk preservation: preliminary study. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2010;46(3):205–12.

Steinbok P, Hukin J. Intracystic treatments for craniopharyngioma. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28(4):E13.

Qiao N. Endocrine outcomes of endoscopic versus transcranial resection of craniopharyngiomas: a system review and meta-analysis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2018;169:107–15.

Alotaibi NM, et al. Physiologic growth hormone-replacement therapy and craniopharyngioma recurrence in pediatric patients: a meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2018;109:487–496.e1.

Smith TR, et al. Physiological growth hormone replacement and rate of recurrence of craniopharyngioma: the Genentech National Cooperative Growth Study. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2016;18(4):408–12.

Shen L, et al. Growth hormone therapy and risk of recurrence/progression in intracranial tumors: a meta-analysis. Neurol Sci. 2015;36(10):1859–67.

Kilday JP, et al. Intracystic interferon-alpha in pediatric craniopharyngioma patients: an international multicenter assessment on behalf of SIOPE and ISPN. Neuro-Oncology. 2017;19(10):1398–407.

Bock RD. Multiple prepubertal growth spurts in children of the Fels Longitudinal Study: comparison with results from the Edinburgh Growth Study. Ann Hum Biol. 2004;31(1):59–74.

Butler GE, McKie M, Ratcliffe SG. The cyclical nature of prepubertal growth. Ann Hum Biol. 1990;17(3):177–98.

Guadagno E, et al. Can recurrences be predicted in craniopharyngiomas? beta-catenin coexisting with stem cells markers and p-ATM in a clinicopathologic study of 45 cases. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36(1):95.

Coury JR, et al. Histopathological and molecular predictors of growth patterns and recurrence in craniopharyngiomas: a systematic review. Neurosurg Rev. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-018-0978-5.

Dandurand C, et al. Adult craniopharyngioma: case series, systematic review, and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery. 2018;83:631.

Clark AJ, et al. A systematic review of the results of surgery and radiotherapy on tumor control for pediatric craniopharyngioma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29(2):231–8.

Du C, et al. Ectopic recurrence of pediatric craniopharyngiomas after gross total resection: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2016;32(8):1523–9.

Gillis J, Loughlan P. Not just small adults: the metaphors of paediatrics. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(11):946–7.

Patel VS, et al. Outcomes after endoscopic endonasal resection of craniopharyngiomas in the pediatric population. World Neurosurg. 2017;108:6–14.

Alalade AF, et al. Suprasellar and recurrent pediatric craniopharyngiomas: expanding indications for the extended endoscopic transsphenoidal approach. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2018;21(1):72–80.

Cavallo LM, et al. The endoscopic endonasal approach for the management of craniopharyngiomas: a series of 103 patients. J Neurosurg. 2014;121(1):100–13.

Jang YJ, Kim SC. Pneumatization of the sphenoid sinus in children evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Rhinol. 2000;14(3):181–5.

Wijnen M, et al. Excess morbidity and mortality in patients with craniopharyngioma: a hospital-based retrospective cohort study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;178(1):95–104.

Olsson DS, et al. Excess mortality and morbidity in patients with craniopharyngioma, especially in patients with childhood onset: a population-based study in Sweden. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):467–74.

Park SW, et al. Tumor origin and growth pattern at diagnosis and surgical hypothalamic damage predict obesity in pediatric craniopharyngioma. J Neuro-Oncol. 2013;113(3):417–24.

van Iersel L, et al. The development of hypothalamic obesity in craniopharyngioma patients: a risk factor analysis in a well-defined cohort. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(5):e26911.

Muller HL. Hypothalamic involvement in craniopharyngioma-Implications for surgical, radiooncological, and molecularly targeted treatment strategies. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(5):e26936.

Puget S, et al. Pediatric craniopharyngiomas: classification and treatment according to the degree of hypothalamic involvement. J Neurosurg. 2007;106(1 Suppl):3–12.

Van Gompel JJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging–graded hypothalamic compression in surgically treated adult craniopharyngiomas determining postoperative obesity. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28(4):E3.

Muller HL, et al. Post-operative hypothalamic lesions and obesity in childhood craniopharyngioma: results of the multinational prospective trial KRANIOPHARYNGEOM 2000 after 3-year follow-up. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;165(1):17–24.

Muller HL, et al. Xanthogranuloma, Rathke’s cyst, and childhood craniopharyngioma: results of prospective multinational studies of children and adolescents with rare sellar malformations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(11):3935–43.

Pascual JM, et al. Displacement of mammillary bodies by craniopharyngiomas involving the third ventricle: surgical-MRI correlation and use in topographical diagnosis. J Neurosurg. 2013;119(2):381–405.

Prieto R, et al. Preoperative assessment of craniopharyngioma adherence: magnetic resonance imaging findings correlated with the severity of tumor attachment to the hypothalamus. World Neurosurg. 2018;110:e404–26.

Colquitt JL, et al. Surgery for weight loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014(8):Cd003641. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003641.pub4.

Holmer H, et al. Reduced energy expenditure and impaired feeding-related signals but not high energy intake reinforces hypothalamic obesity in adults with childhood onset craniopharyngioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(12):5395–402.

Geerling JC, et al. Paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus: axonal projections to the brainstem. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518(9):1460–99.

Haliloglu B, Bereket A. Hypothalamic obesity in children: pathophysiology to clinical management. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2015;28(5-6):503–13.

Nagai K, et al. SCN output drives the autonomic nervous system: with special reference to the autonomic function related to the regulation of glucose metabolism. Prog Brain Res. 1996;111:253–72.

Harz KJ, et al. Obesity in patients with craniopharyngioma: assessment of food intake and movement counts indicating physical activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(11):5227–31.

Castro-Dufourny I, Carrasco R, Pascual JM. Hypothalamic obesity after craniopharyngioma surgery: treatment with a long acting glucagon like peptide 1 derivated. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr (English ed). 2017;64(3):182–4.

Hamilton JK, et al. Hypothalamic obesity following craniopharyngioma surgery: results of a pilot trial of combined diazoxide and metformin therapy. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2011;2011:1–7.

Ni W, Shi X. Interventions for the treatment of craniopharyngioma-related hypothalamic obesity: a systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2018;118:e59.

McCarty CA, Nanjan MB, Taylor HR. Vision impairment predicts 5 year mortality. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(3):322–6.

Jacobsen MF, et al. Predictors of visual outcome in patients operated for craniopharyngioma - a Danish national study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96(1):39–45.

Drimtzias E, et al. The ophthalmic natural history of paediatric craniopharyngioma: a long-term review. J Neuro-Oncol. 2014;120(3):651–6.

Wan MJ, et al. Long-term visual outcomes of craniopharyngioma in children. J Neuro-Oncol. 2018;137(3):645–51.

Astradsson A, et al. Visual outcome, endocrine function and tumor control after fractionated stereotactic radiation therapy of craniopharyngiomas in adults: findings in a prospective cohort. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(3):415–21.

Abrams LS, Repka MX. Visual outcome of craniopharyngioma in children. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1997;34(4):223–8.

Lee MJ, Hwang J-M. Initial visual field as a predictor of recurrence and postoperative visual outcome in children with craniopharyngioma. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2012;49:38.

Prieto R, Pascual JM, Barrios L. Optic chiasm distortions caused by craniopharyngiomas: clinical and magnetic resonance imaging correlation and influence on visual outcome. World Neurosurg. 2015;83(4):500–29.

Danesh-Meyer HV, et al. In vivo retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measured by optical coherence tomography predicts visual recovery after surgery for parachiasmal tumors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(5):1879–85.

Bialer OY, et al. Retinal NFL thinning on OCT correlates with visual field loss in pediatric craniopharyngioma. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013;48(6):494–9.

Mediero S, et al. Visual outcomes, visual fields, and optical coherence tomography in paediatric craniopharyngioma. Neuroophthalmology. 2015;39(3):132–9.

Barbosa DAN, et al. The hypothalamus at the crossroads of psychopathology and neurosurgery. Neurosurg Focus. 2017;43(3):E15.

Ozyurt J, Muller HL, Thiel CM. A systematic review of cognitive performance in patients with childhood craniopharyngioma. J Neuro-Oncol. 2015;125(1):9–21.

Fjalldal S, et al. Hypothalamic involvement predicts cognitive performance and psychosocial health in long-term survivors of childhood craniopharyngioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(8):3253–62.

Memmesheimer RM, et al. Psychological well-being and independent living of young adults with childhood-onset craniopharyngioma. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59(8):829–36.

Ondruch A, et al. Cognitive and social functioning in children and adolescents after the removal of craniopharyngioma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;27(3):391–7.

Pascual JM, et al. Craniopharyngiomas primarily involving the hypothalamus: a model of neurosurgical lesions to elucidate the neurobiological basis of psychiatric disorders. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:e1245.

Hoffmann A, et al. First experiences with neuropsychological effects of oxytocin administration in childhood-onset craniopharyngioma. Endocrine. 2017;56(1):175–85.

Daubenbuchel AM, et al. Oxytocin in survivors of childhood-onset craniopharyngioma. Endocrine. 2016;54(2):524–31.

Dillingham CM, et al. How do mammillary body inputs contribute to anterior thalamic function? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;54:108–19.

Vann SD, Nelson AJ. The mammillary bodies and memory: more than a hippocampal relay. Prog Brain Res. 2015;219:163–85.

Tanaka Y, et al. Amnesia following damage to the mammillary bodies. Neurology. 1997;48(1):160–5.

Savastano LE, et al. Korsakoff syndrome from retrochiasmatic suprasellar lesions: rapid reversal after relief of cerebral compression in 4 cases. J Neurosurg. 2018;128(6):1731–6.

Kahn EA, Crosby EC. Korsakoff’s syndrome associated with surgical lesions involving the mammillary bodies. Neurology. 1972;22(2):117–25.

Crom DB, et al. Health status in long-term survivors of pediatric craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosci Nurs. 2010;42(6):323–8.

Poretti A, et al. Outcome of craniopharyngioma in children: long-term complications and quality of life. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46(4):220–9.

Pedreira CC, et al. Health related quality of life and psychological outcome in patients treated for craniopharyngioma in childhood. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19(1):15.

Laffond C, et al. Quality-of-life, mood and executive functioning after childhood craniopharyngioma treated with surgery and proton beam therapy. Brain Inj. 2012;26(3):270–81.

Heinks K, et al. Quality of life and growth after childhood craniopharyngioma: results of the multinational trial KRANIOPHARYNGEOM 2007. Endocrine. 2018;59(2):364–72.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sweeney, K.J., Mottolese, C., Villanueva, C., Beuriat, P.A., Szathmari, A., Di Rocco, F. (2020). Adult Versus Paediatric Craniopharyngiomas: Which Differences?. In: Jouanneau, E., Raverot, G. (eds) Adult Craniopharyngiomas. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41176-3_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41176-3_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-41175-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-41176-3

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)