Abstract

Objective

Congregate living settings supporting individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) have experienced unprecedented challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study aimed to explore the development and utilization of infection control policies in congregate living settings supporting individuals with IDD during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

This qualitative study employed an interpretive description using semi-structured interviews involving administrative personnel from agencies assisting those with IDD residing in Developmental Services congregate living settings in Ontario, Canada.

Results

Twenty-two semi-structured interviews were conducted with individuals from 22 agencies. Thematic analysis revealed three categories: Development of infection control policies, Implementation of infection control policies, and Impact of infection control policies. Each category yielded subsequent themes. Themes from the Development of infection control policies category included New responsibilities and interpreting the grey areas, and Feeling disconnected and forgotten. Four themes within the Implementation of infection control policies category included, “It’s their home” (i.e. difficulty balancing public health guidance and organizational values), Finding equipment and resources (e.g. supports and barriers), Information overload (i.e. challenges agencies faced when implementing policies), and Emerging vaccination (i.e. perspective of agencies as they navigate vaccination for clients and staff). The category of Impact of infection control policies had one theme—Fatigue and burnout, capturing the impact of policies on stakeholders in congregate living settings.

Conclusion

Agencies experienced difficulties develo** and implementing infection control policies, impacting the clients they serve and their families and staff. Public health guidance should be tailored to each congregate living setting rather than generally applied.

Résumé

Objectif

Les lieux d’hébergement collectif pour les personnes ayant une déficience intellectuelle ou de développement (DID) ont affronté des défis sans précédent durant la pandémie de la COVID-19. La présente étude vise à explorer l’élaboration et l’utilisation des politiques de prévention des infections dans les lieux d’hébergement collectif pour les personnes ayant une DID durant la pandémie de la COVID-19.

Méthodes

Cette étude qualitative repose sur la description interprétative lors d’entrevues semi-structurées auprès du personnel administratif des organismes qui viennent en aide aux personnes ayant une DID et résidant dans des lieux d’hébergement collectif en Ontario, au Canada.

Résultats

Au total, 22 entrevues semi-structurées ont été effectuées auprès de personnes provenant de 22 organismes. L’analyse thématique a révélé trois catégories : Élaboration des politiques de prévention des infections, mise en œuvre des politiques de prévention des infections, et impacts des politiques de prévention des infections. Chaque catégorie a généré des thèmes subséquents. Les thèmes liés à l’élaboration des politiques de prévention des infections comprenaient les nouvelles responsabilités et l’interprétation des zones grises, et le sentiment de détachement et d’avoir été oublié. Quatre thèmes découlant de la mise en œuvre des politiques de prévention des infections comprenaient « c’est leur maison » (c’est-à-dire difficulté d’équilibrer les mesures de santé publique et les valeurs organisationnelles), trouver de l’équipement et des ressources (p. ex., mesures de soutien et obstacles), surcharge d’information (c’est-à-dire les défis qu’ont dû affronter les organismes lors de la mise en œuvre des politiques) et la vaccination émergente (notamment la perspective des organismes lorsqu’ils ont dû composer avec le processus de vaccination pour la clientèle et le personnel). La catégorie des impacts des politiques de prévention des infections avait un thème : la fatigue et l’épuisement professionnel, saisissant les impacts des politiques de prévention des infections dans les lieux d’hébergement collectif sur ses intervenants.

Conclusion

Les organismes ont éprouvé des difficultés lors de l’élaboration et la mise en œuvre de politiques de prévention des infections, touchant ainsi leurs clients, leurs familles et leurs employés. Les mesures de santé publique devraient plutôt être adaptées à chaque lieu d’hébergement collectif, et non pas appliquées de façon générale.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since the beginning of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 pandemic, commonly known as the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals with disabilities have experienced significant challenges (Dickinson et al., 2020; Jumreornvong et al., 2020; Majnemer et al., 2021). One predominant challenge relates to ensuring that these individuals receive appropriate and safe support in their activities of daily living (Dickinson et al., 2020; Jalali et al., 2020; Jumreornvong et al., 2020; Qi & Hu, 2020).

Long-term care living settings have been a predominant focus during the COVID-19 pandemic due to outbreaks in these facilities and the subsequent alarming consequences, including a high mortality rate (Rotenberg et al., 2021). In contrast, other congregate living settings, such as group homes for individuals with disabilities, have received minimal attention (Rotenberg et al., 2021) despite experiencing outbreaks of COVID-19 (Hall, 2020).

Intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) as defined from a medical perspective in the DSM-5 is characterized by an IQ score between 70 and 75 and difficulty reasoning, planning and abstract thinking (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Importantly, diagnostic criteria emphasize the consideration of the ability of the individual to function within the world (Nevill & Havercamp, 2013). Individuals with intellectual disability may also be diagnosed with other developmental disabilities such as Down syndrome or motor disabilities such as cerebral palsy, which may increase their need for support for tasks of daily living (Majnemer et al., 2021). In Ontario, a recent analysis found that those living with IDD have a 1.28 greater risk of contracting COVID-19 compared to adults without IDD (Lunsky et al., 2021). Individuals with IDD residing in congregate living settings are at a greater risk of contracting COVID-19 and experiencing severe outcomes (Landes et al., 2020; Public Health England, 2020).

Reasons for the increased risk of both contracting COVID-19 and experiencing severe outcomes experienced by individuals with IDD are a combination of environmental and personal factors. Congregate living settings experience an increased risk of virus transmission due to the nature of these settings, such as the consistent flow of support staff entering and exiting the homes (FitzGerald et al., 2022; Hassiotis et al., 2020). Moreover, individuals with IDD may require assistance with activities of daily living that cannot be provided in a physically distant manner (FitzGerald et al., 2022; Perera et al., 2020). Medical comorbidities, such as diabetes, obesity, and chronic respiratory disease, which may increase the risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19, are also more likely to be present in this population (Campanella et al., 2021; Hassiotis et al., 2020).

At the start of the pandemic, a small number of media reports began to appear regarding COVID-19 outbreaks in congregate living settings providing support to those with IDD in Ontario (Hall, 2020). However, it is uncertain how congregate living agencies developed and implemented their infection control policies in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the potential harm associated with contracting COVID-19 for individuals with IDD in congregate living settings, there was an immediate need to understand the experiences of agencies. The aim of this study was to explore the development and utilization of infection control policies by agencies supporting individuals with IDD in congregate living settings during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

This qualitative study conducted semi-structured interviews with administrative personnel from agencies providing support to individuals residing in Developmental Services (DS) congregate living settings in Ontario, Canada. The methodological approach used was interpretive description (ID). ID is an approach that explores clinical questions from an applied disciplinary grounding, with an appreciation for the conceptual and contextual realm in which the target audience is positioned (Thorne, 2016). ID seeks to understand the social and environmental forces that influence a phenomenon and use the acquired information to inform clinical practice (Burdine et al., 2020). This study protocol was approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (#13019).

Research team and relationship to the topic

ID, like other approaches to qualitative research, recognizes that research is influenced by researchers, so it is important to declare our lens and roles. The primary investigator, BDR, is an occupational therapist with a research interest in individuals with IDD in community settings. GR formally served as senior management and as a practicing psychologist in the role of clinical director within an organization providing services to individuals with IDD in a congregate living setting in Ontario. MF is an individual with a congenital physical disability familiar with shared support services provided in the community within Ontario. EF has worked with individuals with IDD and has a research interest focused on infection control in congregate living settings for individuals with IDD. AC and LG were student occupational therapists who assisted with data collection and analysis. MR and RY are disability research trainees who assisted with the environmental scan, interviews, transcription and compilation of the data. HF served as the research assistant for the project.

Selecting agencies

An environmental scan was completed by members of the research team to identify existing congregate living agencies that support adults with IDD across the province of Ontario. The website thehealthline.ca (thehealthline.ca Information Network, 2021) is a nonprofit website providing information about health and social services across municipalities in Ontario. Under the main heading of “Persons with Disabilities”, the subcategory of “Housing and Residential Care” was used to identify agencies. One hundred sixty-six agencies across Ontario were identified. Due to the open-source nature of the website, the list of agencies was reviewed by GR because of their awareness of the DS sector and ability to identify agencies that met the research team’s eligibility criteria. In total, 146 agencies met the inclusion criteria in the final environmental scan. Twenty agencies were removed—twelve entries did not provide congregate living services or did not provide services for individuals with IDD, and eight agencies did not provide services to adults with IDD (e.g. provided services solely to children) or were duplicate records.

Data collection

Initially, we purposefully selected agencies based on demographic data collected from the environmental scan in groups of 10, which included geographic location, population, and services offered. However, the response rate was low, so recruitment was opened to all agencies. Additionally, we found that for many agencies, although their geographic head office was in one location, it was possible for the agency to offer services across multiple municipal boundaries. Therefore, the focus shifted to ensuring that the data that were collected were representative of experiential differences between organizations. Data were collected between March 30, 2021 and May 15, 2021. Interviews were conducted over the online platform Zoom (Zoom Video Communications Inc, 2021) using a semi-structured interview guide. Questions explored participants’ experiences develo** and implementing infection control policies and procedures within their agency prior to, and during, the COVID-19 pandemic. Interviews were manually transcribed verbatim by members of the research team. All identifying personal information and information that could possibly identify the agency were anonymized to maintain confidentiality. Interviews typically involved one participant; however, four interviews were conducted with multiple participants given agencies’ preference. Additionally, two interviews were conducted over two time points given the length of the interview. One agency expressed interest in being interviewed, but the representative did not arrive for the interview and did not respond to subsequent attempts to reschedule.

Data analysis

Data collection and analysis occurred concurrently. A subgroup of the research team was primarily responsible for data analysis. The subgroup met weekly to discuss any issues with the interview process and identify issues occurring in early interviews or changes to Ontario’s pandemic response that required further exploration.

The team employed a constant comparative approach (Thorne, 2016) across the transcripts with the goal of identifying similarities and differences between agencies. Each member of the data analysis team worked independently to identify patterns across transcripts, reviewing a small number of transcripts concurrently on a weekly basis to identify patterns, potential categories, and then themes across transcripts (Thorne, 2016).

An ID methodological approach encourages researchers to discuss research findings with individuals familiar with the phenomenon and practice context being explored during data analysis to ensure depth of description and coherence within interpretation through a process of independent scrutiny (Burdine et al., 2020; Thorne, 2016). Our preliminary thematic analysis involving 10 interviews was discussed with an individual familiar with the experiences of DS agencies during the COVID-19 pandemic but not connected to the research team.

Results

Demographics of agencies and participants

Table 1 describes the participant and agency characteristics. Interviews lasted an average of 1 h and 488 pages of transcribed text were analyzed. All 30 participants had direct involvement in the development and implementation of their agency’s infection control policies. The job titles ranged from accommodations manager to chief executive officer. Participants had been in their current roles for at least 2 years, and approximately half had worked with their agency for over 15 years. The 22 agencies provided a multitude of services extending beyond congregate living, such as day programs, respite services, or independent supported living. Some participants reported that their agency had experienced infectious disease outbreaks prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Eighteen percent (n = 4) reported flu outbreaks and 14% (n = 3) reported experiencing outbreaks during the H1N1 pandemic.

Agency experiences with outbreaks of COVID-19 varied. Fifty-five percent (n = 12) of agencies had experienced an outbreak, and 45% (n = 10) of agencies had not experienced an outbreak. Of the 12 agencies that had experienced an outbreak, the number of outbreaks ranged from one to “dozens”.

Development of infection control policies

The category “Development of infection control policies” was used to organize data when participants were discussing the creation or updating of their infection control policies (Table 2). Two themes emerged from the data in relation to the Development of infection control policies: New responsibilities and interpreting the grey areas, which describes the sources of guidance and the context in which development of policy occurred from the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and Feeling disconnected and forgotten: “We were lumped together”, which describes the relationships between public health units and DS agencies.

New responsibilities and interpreting the grey areas

All agencies had developed infection control policies prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, but participants viewed COVID-19 as different from their previous experiences with infectious diseases.

“[We] had to rely on evolving information and historical practices,” stated Participant 5.

Moreover, Participant 21 referred to their infectious disease policies as now being “living documents”. Participant 8 described the contrast in the following way:

I would describe it as the policy is now much more robust than it would have been 18 months ago. As I say, it was embedded within an emergency preparedness plan that spoke to tornadoes, hurricanes, electrical failures, you know, snowstorms and uh, an outbreak of some kind of infectious disease. That’s obviously now - that component has been pulled out, has been fleshed out. I would describe it more as operational policy now and procedure based on, again, the current circumstances.

Participants relied on multiple sources of guidance to interpret public health information within the context of their setting. Participants identified multiple external sources of guidance when develo** their infection control policies, including the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services (MCCSS) and local public health units. Agencies also identified using internal resources, such as health and safety committees and healthcare professionals on staff, or seeking to hire healthcare professionals to add to their organization.

Regardless of the common guidance established by the MCCSS, which regulates the DS sector, not all agencies took the same approach when develo** or changing policies. Some agencies used their own discretion when considering potential risk.

. . . we’ve found grey areas in between guidelines, uh, to use to our advantage, um, where we can but always with good intentions. And again, it’s always the balance between quality of life and risk. (Participant 9)

In contrast, other agencies had a stronger view of potential harms that could result from not following guidance.

[T]he organization has the liability, so if we are not getting a clear and concrete answer from the ministry or they are saying that we are flexible or we can be lenient in certain areas, we are not going to do that. So we just went to, we just relied back on our own policies and procedures, and, um, the protocols that we put in place to keep everybody safe. (Participant 17)

Feeling disconnected and forgotten: “We were lumped together”

Participants discussed their agencies’ struggles adapting general guidance to align with the characteristics and constraints associated with congregate living settings in the DS sector. Participants described receiving and being expected to implement guidance that was not created for developmental services agencies but instead was created for long-term care settings which are distinct congregate care settings.

[T]he challenge we have is the government and the public health . . . they’re laying the rules down for long-term care facilities but then they just use the same rules for us, and we’re not the same. And they don’t, uh, I don’t think they worked with us sufficiently to understand who we are. So they said ‘you have to do it’. Well, we can’t do it. Well, ‘then you are not in compliance with our requirements’. Well, okay we’ll just do our own thing. (Participant 11)

In addition to experiencing a disconnect with external government agencies and public health, participants also identified a disconnect with their own ministry, the MCCSS. One participant stated:

The ministry were not helpful, um, were not helpful in a timely way[.] [T]hey would come out with a memo or a guideline that was, kind of, would have been helpful two months before. (Participant 8)

In contrast to other participants who highlighted experiences of disconnect, Participant 14 shared positive experiences connecting with their public health unit, stating:

Yeah, our… the primary source that we’ve used is the Public Health Unit. So we have communicated and been in constant contact with them for the last 14 months. Say, here’s the situations that are coming up in our workplace, here’s the scenarios that we support within our services. What is the direction? How does what this clause says in the new directive apply to us? I’m sure you’re aware, there’s, you know, more than enough opinions and interpretations out there.

Implementation of infection control policies

The category of “Implementation of infection control policies” was used when participants discussed the implementation of their infection control policies, and four themes emerged: “It’s their home”, Finding equipment and resources, Information overload, and Emerging vaccination.

“It’s their home”

Participants described how putting information (i.e. public health measures) into practice impacted the individuals and families they support. Participants emphasized the importance of the concept of “home” and spoke to how their agencies’ congregate living settings became less “home-like” due to the implementation of infection control policies and procedures in response to COVID-19. For example:

We always were very you know, um, very very focused on that it’s their home . . . we work in their home, they don’t live in our our workplaces. Um, so we always did really try to create a very family, um, you know oriented, um, kind of feeling and that’s really changed. Um, you know, we have to ensure, you know, physical distance whenever possible, um, so even I think how it’s affected relationships like just within their peer groups and in their homes has changed. (Participant 4)

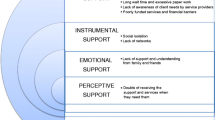

Finding equipment and resources

Another challenge identified when implementing new policy requirements was access to new equipment. One participant shared that their agency was, “woefully short of supplies, and again adequate supplies, and um, supplies that would adhere to standards” (Participant 8).

Participants were left to problem solve the issue of personal protective equipment (PPE) procurement, which led to various strategies. Some agencies made connections with other service providers such as long-term care homes, while others made connections with suppliers or retail locations to ensure a steady supply.

In addition to finding PPE to provide protection for staff, agencies experiencing COVID-19 outbreaks had difficulty managing day-to-day operations and meeting staffing requirements. Describing their outbreak situation, Participant 3 discussed independently working to find a hotel in the community for staff to isolate and recuperate before returning to work:

No, so this whole thing about isolation hotels. No one had even done. So we ran them all wave 1. Um, then our numbers went down, and then we ran it again as a crucial part. Uh, we actually got another hotel in wave 2, um, that we used. But now we’re back at the the other one. And um, and one of the reasons we do that as well is just from a public health measure we know our workers are not able to self-isolate safely at home.

Information overload

Participants discussed the large quantity of incoming information negatively impacting their ability to fully read and comprehend everything, and subsequently implement the necessary changes to their policies and procedures. Additionally, participants noted that they received lengthy updated documents, but these documents often only contained small internal changes.

Information overload, I mean just as far as how even just the changes to the policies and the frequencies of those guidelines, and how back and forth and rapidly that’s all changing. Um, you know a lot of people are having a hard time, um, kee** up with that. (Participant 4)

Emerging vaccination

At the time of the interviews, participants identified that a new component of their infection control policies would be vaccinations. Almost all agencies identified that both their staff and the clients they serve had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. Participants recognized the value of the vaccine but were concerned about issues such as vaccine hesitancy and whether vaccinations could be made mandatory for staff.

[W]e were really early adopters with our vaccine policy and did a great job on that. And we sent that to our lawyer . . . we made sure we had that policy in effect before we started getting our staff vaccinated. I know a lot of agencies just started doing vaccinations. But we had it, we had it ready to roll really early on as well. (Participant 15)

In contrast to the policy-based approach used by Participant 15, Participant 4 shared how their agency chose to focus on education and encouragement.

[W]e can’t make the the vaccine mandatory, we are strongly encouraging it. [W]e’ve provided, um, a lot of information, um, to staff . . . we’re also doing a campaign right now to encourage staff to be vaccinated. Um, it’s called ‘Why We Vaccinate’, um and um, just to try and reduce some of the resistance, um, and some of the misinformation and myths, um, that you know staff are are basing, um, their decisions on.

Impact of infection control policies

The category “Impact of infection control policies” was used when participants discussed the impact of the policies as well as the pandemic itself on their organization. A single theme of “Fatigue and burnout” emerged across stakeholders, including individuals living in the congregate care setting, their families and agency staff.

Fatigue and burnout

The experience of fatigue and burnout was apparent across participants and had a major impact on staff, family members, and individuals supported by agencies. Participants described the impact of different guidance and requirements for the general population compared to the individuals their agencies support in congregate living settings. One participant highlighted the negative and unfair impact of the greater restrictions imposed on the individuals supported by developmental services agencies at both an agency and individual level:

[S]o although you know the general public is allowed to you know, um, with precautions go into a grocery store for example, um, our individuals can’t even if they worked in a grocery store previous to COVID. Um, they’re not, they’re they are really restricted as far as their access outside of the congregate living setting and that’s something that that we’ve struggled with, and I know a lot of developmental services, um, agencies have really struggled with it. It does seem to be unfair and that, um, you know they’re they’re imposing greater restrictions. (Participant 4)

From the perspective of frontline staff, all participants noted fatigue. One participant described the exhaustion:

I think [the staff] were all kind of ho** that we would be out of this boat by now, and um, so the COVID fatigue and everything is really starting to set in with people. Um, they’re done, they’re hot, they’re exhausted. (Participant 6)

Additionally, participants described experiences of COVID fatigue and burnout among the individuals their agencies support and their families. One participant stated: “This [COVID-19] has been hugely, hugely harmful and emotionally draining for those parents” (Participant 8).

Discussion

The findings of this study provide insight into the development, implementation and impact of infection control policies and procedures of agencies providing congregate living services to adults with IDD in Ontario. First, at the start of the pandemic, agencies had to develop and implement new policies and procedures without information that was tailored to their setting. Ontario’s Ministry of Health guidance, directed towards congregate living settings, advised agencies to establish collaborative relationships external to their agencies, as this was important for develo** strong local sector plans (Ministry of Health Ontario, 2020). As the results show, establishing the relationship proved difficult because participants believed that the public health officials lacked an understanding of the DS sector. Parkes et al. (2005) advocated for infectious disease responses to include multiple disciplines. This recommendation is important to continue to prioritize and expand this lens beyond acute healthcare professionals, physicians and nurses, particularly expanding to include professionals with expertise in IDD. For community-based settings, the multidisciplinary healthcare team may include primary care physicians, nurses, psychiatrists and psychologists, rehabilitation professionals and personal support workers. In addition to integrating the knowledge of these health professionals in the development of public health guidance, it is also important to consider the impact of public health guidance on workers providing frontline support. Lunsky et al. (2021) explored the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on staff supporting those with IDD and found that one in four workers reported mental health distress. The inclusion of multidisciplinary health care providers with experience working with individuals with IDD would foster the creation of productive relationships between the DS sector and public health, and optimize the health and well-being of individuals living with IDD during infectious disease outbreaks.

A second finding is the need for public health information to be tailored to DS agencies, including by respecting the human rights of their clients and the philosophical perspective of their person-centred organizational principles (Gjermestad et al., 2017). Although the settings are described as congregate because there are multiple individuals sharing the same living space, this shared space is the home of all individuals residing there. The Ontario Human Rights Tribunal recently stated that “human rights do not end in a pandemic” (JL v. Empower Simcoe, 2020). While evidence strongly demonstrates that individuals with disabilities are vulnerable to severe outcomes upon contraction of COVID-19 (Lunsky et al., 2021), as the pandemic continues, policies should prioritize the balance between protection and personal safety and the importance of full participation in society, focusing on choice and dignity (Majnemer et al., 2021).

To assist with policy development that balances public health and safety with the rights of individuals with IDD in the DS sector, policymakers should consider increasing the opportunity for the multidisciplinary healthcare teams supporting individuals with IDD in community settings to share their knowledge during the development of health recommendations. One of the barriers identified in a sco** review of responses to infectious disease outbreaks in congregate care settings supporting individuals with IDD was that the institutional environment did not allow for effective infection control measures such as isolating residents who are sick from others (FitzGerald et al., 2022). To address this barrier, it is important for public health guidance to reflect the lived experiences of those with disabilities in the community. There is a need to expand public health teams within communities to include rehabilitation professionals, such as occupational therapists or physiotherapists. Not only do rehabilitation professionals bring professional knowledge of the lived experiences of those with disabilities, the rehabilitation lens also includes the theoretical framework of universal design (Lid, 2014), which can be used to assist agencies and the broader community when designing guidance that is congruent with the day-to-day lived experiences of individuals with IDD in congregate settings.

From the perspective of those being supported by agencies and their families, the imposition of health-based restrictions on congregate living settings reduces individuals to being identified by where they live rather than their individual identities as citizens and participating members of their community (Majnemer et al., 2021). Although beyond the scope of this study, participants from agencies offering other housing models, such as supported independent living, mentioned that those living in non-congregate living settings, such as in their own apartment, experienced more freedom than those living in the group homes. Although individuals may reside in congregate living settings, it is important to recognize that they may also have opportunities, such as employment in a grocery store, which did not stop for others because of COVID-19 restrictions. There is a need to recognize that COVID-19 has imposed new burdens on individuals with IDD, their family members, and the staff assisting them on a daily basis. Unlike members of the community not residing in congregate living settings, individuals with IDD residing in congregate living settings are subject to rules restricting their movements and participation in community activities.

Limitations and future directions

The findings presented here have limitations. Interviews were conducted primarily with management of agencies. Understanding the perspective of frontline workers and those with IDD residing in congregate living settings is important to consider and include in future research. Data collection occurred during Ontario’s third wave of COVID-19 during vaccine rollout. Further research is needed to explore how vaccination has changed the development of infectious disease policies within agencies. Future research should also compare the experiences of agencies supporting those with IDD across Canada and internationally during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

The findings of this research study indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic, and related infection control policies and procedures, have significantly impacted DS agencies and staff, as well as the individuals they support and their families. Exploration of the development, implementation, and impact of infection control policies and procedures of agencies providing congregate living services to adults with IDD in Ontario provides valuable insight and context into the current COVID-19 policies. Further research is needed to assist in addressing the gap between general public health guidance and its application to DS congregate-living environments in Ontario.

Contributions to knowledge

What does this study add to existing knowledge?

-

This research demonstrates that public health guidance provided during the COVID-19 pandemic was not adequately adapted to congregate living settings providing support to individuals with IDD (outside of long-term care).

-

This research demonstrates the need for public health guidance and policy developers to account for the implementation challenges in a community-based setting within agencies supporting those with IDD. For example, community agencies require guidance to procure necessary resources such as PPE and strategies to combat information overload, which can be a barrier to policy implementation.

What are the key implications for public health interventions, practice or policy?

-

This research demonstrates the need for public health to work together with professionals supporting people with IDD when develo** guidance and implementing infection control policies, including using a person-centred approach that balances safety measures while respecting human rights and the autonomy of clients.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Neurodevelopmental disorders. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders fifth edition. American Psychiatric Association. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.dsm01

Burdine, J. T., Thorne, S., & Sandhu, G. (2020). Interpretive description: A flexible qualitative methodology for medical education research. Medical Education, 55(1), 336–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14380

Campanella, S., Rotenberg, S., Volpe, T., Balogh, R., & Lunsky, Y. (2021). Including people with developmental disabilities as a priority group in Canada’s COVID-19 vaccination program: Key considerations. Health Care Access Research and Developmental Disabilities. https://www.porticonetwork.ca/web/hcardd/news/-/blogs/research-evidence-regarding-covid-19-and-developmental-disabilities

Dickinson, H., Carey, G., & Kavanagh, A. M. (2020). Personalisation and pandemic: An unforeseen collision course? Disability & Society, 35(6), 1012–1017. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1772201

FitzGerald, E. A., Freeman, M., Rinato, M., & Di Rezze, B. (2022). Responses to infectious disease outbreaks in supported living environments for individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders: A sco** review. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2021.2012007

Gjermestad, A., Luteberget, L., Midjo, T., & Witsø, A. E. (2017). Everyday life of persons with intellectual disability living in residential settings: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Disability & Society, 32(2), 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1284649

Hall, J. (2020). Staff walk out at Markham home for mentally, physically challenged adults after COVID-19 outbreak. The Star. https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2020/04/10/donations-of-protective-gear-pour-in-after-coronavirus-outbreak-at-markham-home-for-people-with-disabilities.html

Hassiotis, A., Ali, A., Courtemanche, A., Lunsky, Y., Lee, L., McIntyre, D. N., van der Nagel, J., & Werner, S. (2020). In the time of the pandemic: Safeguarding people with developmental disabilities against the impact of coronavirus. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 13(2), 63–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2020.1756080

Jalali, M., Shahabi, S., Bagheri Lankarani, K., Kamali, M., & Mojgani, P. (2020). COVID-19 and disabled people: Perspectives from Iran. Disability & Society, 35(5), 844–847. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1754165

JL v. Empower Simcoe (2020). HRTO 880 (CanLII), https://canlii.ca/t/jbm2k, retrieved on 2021-08-03.

Jumreornvong, O., Tabacof, L., Cortes, M., Tosto, J., Kellner, C. P., Herrera, J. E., & Putrino, D. (2020). Ensuring equity for people living with disabilities in the age of COVID-19. Disability & Society, 35(10), 1682–1687. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1809350

Landes, S. D., Turk, M. A., Formica, M. K., McDonald, K. E., & Stevens, J. D. (2020). COVID-19 outcomes among people with intellectual and developmental disability living in residential group homes in New York State. Disability and Health Journal, 13(4), 100969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100969

Lid, I. M. (2014). Universal design and disability: an interdisciplinary perspective. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36(16), 1344–1349. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.931472

Lunsky, Y., Durbin, A., Balogh, R., Lin, E., Palma, L., & Plumptre, L. (2021). COVID-19 positivity rates, hospitalizations and mortality of adults with and without intellectual and developmental disabilities in Ontario, Canada. Disability and Health Journal, 101174. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101174.

Majnemer, A., McGrath, P.J., Baumbusch, J., Camden, C., Fallon, B., Lunsky, Y., Miller, S.P., Sansone, G., Stainton, T., Sumarah, J., Thomson, D., Zwicker, J. (2021). Time to be counted: COVID-19 and intellectual and developmental disabilities. Royal Society of Canada. https://rsc-src.ca/en/covid-19-policy-briefing/time-to-be-counted-covid-19-and-intellectual-and-developmental-disabilities

Ministry of Health Ontario. (2020). COVID-19 guidance: Congregate living for vulnerable populations. https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/coronavirus/docs/2019_cong regate_living_guidance.pdf

Nevill, R. E. A., & Havercamp, S. M. (2013). Intellectual disability. In F. R. Volkmar (Ed.), Encyclopedia of autism spectrum disorders (pp. 1623–1633). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1698-3_1641

Parkes, M. W., Bienen, L., Breilh, J., Hsu, L., McDonald, M., Patz, J. A., Rosenthal, J. P., Sahani, M., Sleigh, A., Waltner-Toews, D., & Yassi, A. (2005). All hands on deck: Transdisciplinary approaches to emerging infectious disease. EcoHealth, 2, 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-005-8387-y

Perera, B., Laugharne, R., Henley, W., Zabel, A., Lamb, K., Branford, D., Courtanay, K., Alexander, R., Purandare, K., Wijeratne, A., Radhakrishnan, V., McNamara, E., Daureeawoo, Y., Sawhney, I., Scheepers, M., Taylor, G., & Shankar, R. (2020). COVID-19 deaths in people with intellectual disability in the UK and Ireland: Descriptive study. BJPsych Open, 6(e123), 1–6 10.1192/bjo.2020.

Public Health England. (2020). Deaths of people identified as having learning disabilities with COVID-19 in England in the spring of 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/933612/COVID-19__learning_disabilities_mortality_report.pdf

Qi, F., & Hu, L. (2020). Including people with disability in the COVID-19 outbreak emergency preparedness and response in China. Disability & Society, 35(5), 848–853. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1752622

Rotenberg, S., Downer, M. B., & Lunsky, Y. (2021). A forgotten high-risk setting: COVID-19 testing in Canadian group homes. Canadian Family Physician Blog. https://www.cfp.ca/news/2021/05/14/514

thehealthline.ca Information Network. (2021). thehealthline.ca. Retrieved October 1, 2021, from https://www.thehealthline.ca/

Thorne, S. (2016). Interpretive description: qualitative research for applied practice.(Second edition). Routledge.

Zoom Video Communications Inc. (2021). Computer software. Retrieved from: https://zoom.us

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by MF, AC, LG, MR, RY, GR and BDR. Data analysis was conducted by MF, AC, LG and BDR. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MF, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (study #13019).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Freeman, M., Crawford, A., Gough, L. et al. Examining the development and utilization of infection control policies to safely support adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities in congregate living settings during COVID-19. Can J Public Health 113, 918–929 (2022). https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-022-00674-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-022-00674-0

Keywords

- COVID-19

- Intellectual disabilities

- Developmental disabilities

- Congregate living

- Infection control policies