Abstract

Background

Super 304H austenitic stainless steel tubes containing 2.3 to 3 (wt.%) of Cu are mainly used in superheaters and reheaters of ultra super critical boilers due their excellent corrosion and oxidation resistance. Cu addition causes precipitation strengthening effect by fine Cu-rich precipitates which evolve during creep conditions and results in increased creep strength. The microstructural evolution of stainless steels during welding significantly affects the material properties.

Methods

In this work, solidification mode microstructure and hot tensile properties of autogenous and filler-added Super 304H gas tungsten arc (GTA) welded tube joints were correlated.

Results

Autogenous welds of Super 304H solidified as austenite with 1.57 % delta ferrite and intercellular (Fe,Cr)23(C,B)6 borocarbides. In filler-added welds, the higher Ni equivalent and addition of carbide stabilizing elements (Nb,Mo) eliminated δ ferrite and segregation of B as borocarbides.

Conclusions

The filler-added welds exhibited superior tensile strength than autogenous welds at both room and high temperature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Efficiency of the power plant strongly depends on the operating steam temperature and pressure. The concern for reducing the CO2 emission and coal consumption leads to the efforts to build power plants operating at higher steam parameters (Brozda 2007; Shu ** et al. 2010; David et al. 2013). Austenitic stainless steels are selected for use in sections of superheaters and reheaters, which require good oxidation and fire side corrosion resistance, in addition to the creep strength. The recent improvements in operating steam temperatures up to 620 °C were achieved through the development of creep-resistant stainless steels, containing Cr, Ni, W, Co, Cu and N. Future plans of increasing the efficiency of the power plants up to 49 % require creep-resistant steels operating at steam temperatures of 760 °C and pressures of 35 MPa (Viswanathan et al. 2005). Super 304H austenitic stainless steel is used in recently installed ultra super critical (USC) power units of Japan operating at steam temperature of about 613 °C (Thomas 2013). Further, Super 304H is listed as a candidate material for superheaters and reheaters in the US program for development of materials for USC with steam temperatures of 760 °C (Viswanathan et al. 2005). Super 304H with nominal composition of 0.1C-18Cr-9Ni-3Cu-Nb-N derives excellent creep strength from the distinct Cu addition which precipitates as fine Cu-rich particle under creep conditions, in addition to NbCrN, Nb(C,N) and M23C6 particles (Li et al. 2010).

The different modes of solidification mechanism (A-AF-FA-F) and the methods to predict the volume percentage of ferrite along with the solidification modes are described in detail elsewhere (Valiente Bermejo 2012). A ternary alloy with a composition of Super 304H is expected to solidify as austenite under equilibrium conditions (Hunter and Ferry 2002). In non-equilibrium cooling conditions such as welding, the solidification sequence of the stainless steel depends on the cooling rate and, in highly alloyed steels such as Super 304H, it may result in local compositional variation due to segregation, which alters the solidified phases at room temperature (Darja Steiner et al. 2011).

Recently, few investigations (Indrani et al. 2011; Yang et al. 2006; Li et al. 2010; Bai et al. 2013; Ha and Jung 2012) were carried out to understand the ageing behaviour of Super 304H alloy at high temperatures and evaluated the effect of varying Cu content on microstructure and mechanical properties of the alloy. Works carried out on weldability studies and high temperature properties of Super 304H weld joints reported the tendency of Super 304H to hot cracking and use of matching Super 304H filler metal as an alternate to Ni-based filler metal (Vekeman et al. 2014; Kim et al. 2014). However, the available information on solidification behaviour of gas tungsten arc (GTA) welds of Super 304H and its effects on high temperature properties are very scant. Hence in this work, an attempt has been made to compare the solidification modes, microstructure and hot tensile properties of autogenous and filler-added GTA-welded tube joints of Super 304H austenitic stainless steel. The amount of alloy segregation, composition of segregated elements in autogenous joints, and the role of alloying elements added in the filler metal to avoid detrimental segregation along with their effects on tensile strength of the joints are discussed in this paper.

Methods

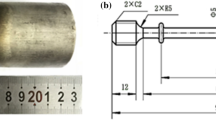

Super 304H austenitic stainless steel tubes of outer diameter 57.1 mm and wall thickness of 3.5 mm were used in this investigation. Chemical composition of the Super 304H tube and filler metal used in this investigation are presented in Table 1. The tensile properties of tube in solution-annealed condition are given in Table 2. For autogenous welds, the joints with square butt preparation with no gap was employed, and for filler-added welds, the joints with single ‘V’ butt preparation was welded using GTAW process. Argon was used as the shielding and purging gas for both cases, with flow rates of 12 and 10 L/min, respectively. The welding parameters used in this investigation are shown in Table 3.

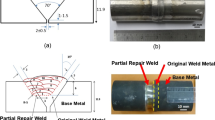

Photographs of the autogenous and filler-added GTA-weld joints are shown in Fig. 1a, b, respectively. To identify the mode of weld solidification, microstructural examinations were carried out by obtaining samples from the weld joints. The samples were prepared using standard metallographic techniques and etched with Glyceregia for 5–10 s to reveal the general structure and with boiling Murakami’s reagent to reveal δ ferrite and carbides. The microstructural examination of the samples was carried out using light optical microscope (OM) with image analysing software, field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM). The compositional variation within the weld regions was analysed using energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) attached with SEM. The δ ferrite measurement in the welds was carried out using ferritescope. The specimens for transverse tensile test were extracted from the weld joints using wire-cut electric discharge machining. Figure 1c represents the dimension of the transverse tensile specimens extracted from the weld joints. Instron universal testing machine (UTM) was used to carry out the tensile testing, under constant crosshead speed mode with a nominal strain rate of 1 × 10−3 S−1. The tensile tests were carried out at four different test temperatures (room temperature (RT), 550 °C, 600 °C and 650 °C). The UTM system was equipped with a three-zone resistance heating furnace for high temperature tests and a computer with data acquisition system for obtaining digital load-elongation data. The photograph of hot tensile test specimens after the test is shown in Fig. 1d. The hardness was measured across the weld centre line using Vickers microhardness tester with a load of 500 g and dwell time of 15 s. The fracture surfaces of the tensile specimens were analysed using SEM to reveal the mode of fracture.

Results

Microstructure

Figure 2a shows the macrograph of the autogenous GTAW joint and it reveals the various regions of the joint, consisting of parent metal (PM), heat-affected zone (HAZ) and fusion zone (FZ). Figure 2b shows the microstructural variation across the joint at low magnification. The micrograph of weld metal (WM) is shown in Fig. 2c, which reveals the presence of austenite (white phase) with δ ferrite (dark phase). Micrograph of the WM at centre of the joint, shown in Fig. 2d, reveals the presence of precipitates both within the austenite grains and in the austenitic grain boundaries. The presence of precipitates within the δ ferrite at the grain boundaries was also revealed in Fig. 2d. Micrograph of weld fusion line shown in Fig. 2e reveals the presence of δ ferrite with mixed morphology and preferential orientation towards the weld centre.

Macrograph of the filler-added GTAW joint is shown in Fig. 3a and the microstructural variation across the joint is shown in Fig. 3b. The WM micrograph of the filler-added weld joint, shown in Fig. 3c, reveals the presence of fully austenitic equiaxed dendritic structure. The grain size of the filler-added WM is coarser (80–100 μm) than the PM (30–40 μm). Micrograph of filler-added WM is shown at higher magnification in Fig. 3d and reveals no δ ferrite. However, it consists of finer interdendritic and grain boundary precipitates than the autogenous weld. The fusion line of filler-added joint is shown in Fig. 3e, which reveals the partially melted zone with epitaxial growth of austenitic grains towards the weld centre with no evidence of δ ferrite.

SEM micrograph of HAZ of the autogenous weld joint is shown in Fig. 4a, and it reveals coarsening of precipitates and austenite grains. Figure 4b shows the SEM micrograph of autogenous WM, which reveals the presence of finer precipitates within austenitic grains and coarse precipitates within the δ ferrite. Chemical composition of the WM region determined by EDS is shown in Fig. 4c, where the composition of alloying elements in WM matches with the PM. In order to determine the type of precipitates available within δ ferrite, the sample was etched with Murakami’s reagent near boiling point. Murakami’s reagent preferentially etches the carbides at the austenite grain boundaries and δ ferrite. Micrograph of WM etched with Murakami’s reagent is shown in Fig. 4d and it shows the intercellular segregation of alloying elements (grey phase). EDS line scan across the grey phase (L1) for elemental variation in Cr and Ni is presented in Fig. 4e. The marginal increase in Cr concentration and reduction in Ni concentration across the grey phase suggests the presence of δ ferrite. The composition of the δ ferrite region was measured by EDS analysis on the spot (S1) and found to be rich in Fe, Cr, B and C.

SEM micrographs of the filler-added weld joint are shown in Fig. 5 and the WM micrograph shown in Fig. 5a reveals randomly oriented fully austenitic dendritic grains with no δ ferrite. The elemental spectrum of the WM region marked in Fig. 5a was determined by EDS and presented in Fig. 5b. The WM composition is similar to the composition of the filler metal added to the weld. The fusion line and HAZ of the filler-added weld joint, shown in Fig. 5c, reveals the columnar austenitic grains in the weld close to the fusion line with no δ ferrite and few coarse precipitates within the coarsened austenitic grains of the HAZ. The WM at higher magnification, shown in Fig. 5d, reveals the presence of interdendritic and grain boundary precipitates. The EDS elemental map** of Nb, Mo and C for the WM region marked in Fig. 5d is shown in Fig. 5e, f, g, respectively. The precipitates are confirmed to be the rich in Nb, Mo and C; segregation of other alloying elements is not observed from the EDS analysis.

Ferrite measurement

The amount of δ ferrite in the WM of autogenous and filler-added weld joints was measured using ferritescope and presented in Table 4. The average ferrite content of the autogenous WM is found to be 1.57 % and no δ ferrite is found in the WM of filler-added joint. The amount of δ ferrite determined using the ferritescope for autogenous WM is much lower than volume of dark phase (termed as δ ferrite) in the microstructure. The amount of dark phase in autogenous weld is found to be 8.23 % by image analysis.

Tensile properties

The engineering stress-strain curves of autogenous and filler-added weld joints at various test temperatures are shown in Fig. 6a, b, respectively, and the tensile properties are presented in Table 5. The RT tensile strength of autogenous weld joint is lesser than the PM strength (−2 %), with failure located in the weld centre. In case of filler-added joint, the tensile strength exceeded the PM strength (+6 %), with failure in the parent material. The tensile strength of both autogenous and filler-added weld joints decreased with increase in test temperature. The tensile strength decreased by 31 % in autogenous weld joints and by 36 % in filler-added weld joint with increase in test temperature from RT to 650 °C. The elongation of both the autogenous and filler weld joints decreased with increase in test temperature.

Hardness

The mid-thickness microhardness measured across the autogenous and filler-added weld joint are shown in Fig. 7. The WM of filler-added joint recorded higher hardness than the WM of autogenous joint; steep hardness variations were observed within the WM region of both autogenous and filler-added joints. The lowest hardness value was recorded in the WM region close to the FL for both autogenous and filler-added joints. The HAZ region of both the autogenous and filler-added joints has not undergone softening due to the weld thermal cycles and retained its hardness equivalent to that of the PM (175 HV).

Fracture surfaces

The fracture surface of autogenous joint tensile tested at RT and 550 °C is shown in Fig. 8a, b, respectively. The reduction in cross-sectional area of the specimen tested at RT is higher (refer to Fig. 8a) than that of the specimen tested at 550 °C. The high magnification SEM fractograph of autogenous joints tested at RT and 550 °C is shown in Fig. 8c, d and invariably consists of dimples. Since the fracture of the autogenous joints was located in the WM, the dimple sizes closely match with that of the dendrite size. The precipitates segregated along the grain boundaries (marked by arrow) assisted in crack initiation.

The SEM fractographs of filler-added joint tested at RT and 550 °C is shown in Fig. 8e, f, respectively, which reveals a similar behaviour with much lesser reduction in the cross-sectional area of the specimen tested at 550 °C than at RT. The fracture in the filler-added joints was located at the PM, which is evident from the absence of dendritic structure in the high magnification fractographs shown in Fig. 8g, h. The specimen tested at 550 °C reveals coarse and fewer dimples than the specimen tested at RT (refer to Fig. 8g). Flat featureless regions which are much prominent in specimen tested at 550 °C evidence the reduction in elongation of the joint at high temperatures. The Nb-rich precipitates (marked by arrow) associated with the voids in the fracture surface of RT specimen act as the crack initiation site.

Discussion

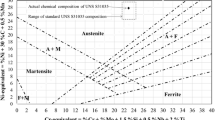

The mode of solidification in stainless steels is strongly dependent on the chemical composition which is usually represented as Cr and Ni equivalents (Valiente Bermejo 2012; Brooks et al. 1983). The WRC-1992 constitution diagram Cr/Ni equivalents are commonly used to predict the solidification mode and ferrite content of the weld based on composition of the alloy (Srinivasan et al. 2012). The Cr and Ni equivalent of autogenous weld metal is determined as 18.2 and 14.7 %, respectively. Similarly, the Cr and Ni equivalent for filler-added weld metal is determined as 19.4 and 23.1 %. The welds of both autogenous and filler-added joints are predicted to solidify as primary austenite (A-mode) with no δ ferrite in the WM (as per WRC-1992 diagram). The WM of autogenous weld consists of 1.57 % δ ferrite (refer to Table 4), which is in contrary to the predicted weld metal microstructure.

The autogenous weld solidifies by epitaxial growth and a plane front solidification zone near the fusion line (refer to Fig. 2d) and transforms to cellular mode with microsegregation to the cellular boundaries (refer to Fig. 2b) (Elmer et al. 1989). The vertical section of the Fe-Ni-Cr ternary diagram is shown in Fig. 9 with lines representing the compositional range of the Super 304H. The first solidifying structure in the weld depends on the side in which the eutectic liquidus nominal composition lies and the remaining liquid may solidify as eutectic or peritectic based on the level of segregation (Brooks and Thompson 1991).

Vertical section of Fe-Ni-Cr ternary diagram at 70 % Fe content (Brooks et al. 1983)

The autogenous weld of Super 304H first solidifies as δ ferrite near the fusion line due to the peritectic solidification, followed by eutectic single austenite solidification phase evident from the cellular structure of austenite in the weld centre. The austenite continues to grow into the peritectic δ ferrite by solid state transformation, with austenite as the more stable phase. Metalographically hard to distinguish peritectic and eutectic ferrite was retained in the intercellular austenitic/austenitic and austenitic/δ-ferrite boundaries of the autogenous weld (refer to Fig. 2b), as the solid state transformation of δ ferrite to austenite is not complete due to segregation or cooling conditions (Brooks et al. 1983). The addition of B to stainless steel enhances the hardenability and creep strength, however the B in solid solution is beneficial and precipitated borides are detrimental. The segregation of Fe, Cr, B and C (refer to Fig. 4f) in the intercellular region of the austenite reveals the presence of (Fe,Cr)23(C,B)6 borocarbides (Hoffman and ASM 1989; Karlsson et al. 1982). The limited solubility of B in austenitic stainless steel of 30 PPM at 900 °C may cause the excess B to segregate along the grain boundaries and combine with Cr and Fe to form a low melting eutectic with the austenite (Carinci 1994). Such eutectic formation and borocarbide precipitation within the ferrite stringers alter the composition of the solidifying liquid ahead of the austenite/liquid interface and hinder the liquid to solidify as austenite in the intercellular boundaries.

In case of filler-added weld, the WM is fully austenitic with no δ ferrite as predicted (refer to Fig. 5a) and it is attributed to the increased addition of Ni, Nb, Mo and N to the weld metal. The higher Ni equivalent of filler-added WM resulted in A mode of solidification with primary austenite dendrites as single phase (refer to Fig. 5d) (Bonollo et al. 2004). The precipitation of (Fe,Cr)23(C,B)6 was to be suppressed by the Mo, Nb and N addition to the WM of filler-added joint. The formation of (Nb,Mo)C clusters or (Nb,Mo) carbonitrides (refer to Fig. 5e, f, g) prevents the supplement of C to the grain boundaries and retards the formation of detrimental carboborides in filler-added joint (Hara et al. 2004).

The failure of the autogenous weld joint was located at the weld centre regardless of the test temperature, recorded the lowest hardness in the weld joint (refer to Fig. 7). In single pass autogenous weld, the weld metal solidifies as coarse columnar grains by epitaxial growth towards the weld centre with preferential orientation, which may result in a weak centre line in the weld (Villafuerte and Kerr 1990). The higher tensile strength of filler-added joint than the autogenous joint at all test temperatures is attributed to the fine Nb- and Mo-rich carbides. In turn, B retained in the austenitic matrix without precipitation of detrimental carboborides in the WM of filler-added joint. The retention of elemental B in the WM increases the hardenability and thereby resulted in increased strength of the filler-added joint. The reduction in the strength values of weld joints with increase in test temperature is attributed to the accelerated recovery process (Choudhary and Rao Palaparti 2012).

Conclusions

-

1.

Autogenously welded GTAW joints of Super 304H austenitic stainless steel resulted in weld metal with austenite and δ ferrite (1.57 %). Boron tends to segregate along the intercellular boundaries to form (Fe,Cr)23(C,B)6 borocarbides.

-

2.

In the filler-added GTAW joints, the increased Mo, Nb and N content suppressed the precipitation of coarse borocarbides by formation of (Nb,Mo)C clusters or (Nb,Mo) carbonitrides and retained elemental B within the matrix to increase the hardenability of the joint.

-

3.

Autogenous GTAW joints exhibited inferior room temperature and high temperature tensile strength compared to filler-added GTAW joints with increased austenite formers (Ni) and carbide formers (Nb and Mo).

References

Bai, J. W., Liu, P. P., Zhu, Y. M., et al. (2013). Coherent precipitation of copper in Super 304H austenite steel. J Mater Sci Eng A, 584, 57–62.

Bonollo, F., Tiziani, A., Tovo, R., et al. (2004). Superaustenitic stainless steels: the microstructure and fatigue strength of welded joints. J Weld Int, 18, 24–30.

Brooks, J. A., & Thompson, A. W. (1991). Microstructural development and solidification cracking susceptibility of austenitic stainless steel welds. J Int Mater Rev, 36, 16–44.

Brooks, J. A., West, A. J., & Thompson, A. W. (1983a). Effect of weld composition and microstructure on hydrogen assisted fracture of austenitic stainless steels. J Metall Trans A, 14, 75–84.

Brooks, J. A., Williams, J. C., & Thompson, A. W. (1983b). Microstructural origin of the skeletal ferrite morphology of austenitic stainless steel welds. J Metall Trans A, 14A, 1271–1281.

Brozda, J. (2007). New generation austenitic steels used in supercritical power industry plant. J Welding International, 21, 512–520.

Carinci, G. M. (1994). Grain boundary segregation of boron in an austenitic stainless steel. J Appl Surf Sci, 76, 266–271.

Choudhary, B. K., & Rao Palaparti, D. P. (2012). Comparative tensile flow and work hardening behaviour of thin section and forged thick section 9Cr-1Mo ferritic steel in the framework of voce equation and Kocks-Mecking approach. Journal of Nuclear Materials, 430, 72–81.

Darja Steiner, P., Grega, K., Miran, P., et al. (2011). Differential scanning calorimetry study of the solidification sequence of austenitic stainless steel. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 105, 251–257.

David, S. A., Siefert, J. A., & Feng, Z. (2013). Welding and weldability of candidate ferritic alloys for future advanced ultrasupercritical fossil power plants. J Sci Technol Weld Joining, 18, 632–651.

Elmer, J. W., Allen, S. M., & Eagar, T. W. (1989). Microstructural development during solidification of stainless steel alloys. J Metall Trans A, 20, 2117–2131.

Ha, V. T., & Jung, W. S. (2012). Creep behavior and microstructure evolution at 750 °C in a new precipitation strengthened heat resistant austenitic stainless steel. J Mater Sci Eng A, 558, 103–111.

Hara, T., Asahi, H., Uemori, R., et al. (2004). Role of combined addition of niobium and boron and of molybdenum and boron on hardnenability in low carbon steels. J ISIJ Int, 44, 1431–1440.

Hoffman, J. P., & ASM, D. j. (1989). The distribution of boron in stainless steels as revealed by a nuclear technique. J S Afr Inst Min Metal, 89, 81–87.

Hunter, A., & Ferry, M. (2002). Phase formation during solidification of AISI 304 austenitic stainless steel. J Scripta Mater, 46, 253–258.

Indrani, S., Amankwah, E., Kumar, N. S., et al. (2011). Microstructure and mechanical properties of annealed SUS 304H austenitic stainless steel with copper. J Mater Sci Eng A, 528, 4491–4499.

Karlsson, L., Andren, H. O., & Nord, H. (1982). Grain boundary segregation in an austenitic stainless steel containing boron - an atom probe study. J Scripta Metallurgica, 16, 297–302.

Kim, M. Y., Kwak, S. C., Choi, I. S., et al. (2014). High-temperature tensile and creep deformation of cross-weld specimens of weld joint between T92 martensitic and Super304H austenitic steels. J Mater Character, 97, 161–168.

Li, X. M., Zou, Y., Zhang, Z. W., & Zou, Z. D. (2010). Microstructure evolution of a novel Super304H steel aged at high temperatures. J Mater Trans, 51, 305–309.

Shu **, T., Zhen Hua, W., Shi Chang, C., et al. (2010). Hot deformation behavior of Super304H austenitic heat resistant steel. J Miner Metall Mater, 17, 167–172.

Srinivasan, G., Bhaduri, A. K., Albert, S. K., et al. (2012). Effect of phosphorous and silicon on hot cracking susceptibility of 14Cr-15Ni-2.3Mo Ti-modified fully austenitic stainless steel. J Weld World, 56, 2–13.

Thomas, B. G. (2013). Recent Advances in Steels for Coal Fired Power Plant: A Review. J Trans Indian Inst Met, 66, 631–640.

Valiente Bermejo, M. A. (2012). Henry Granjon Prize Competition 2012 Winner Category B: Materials Behaviour and Weldability Influence of the [Creq + Nieq] alloy level on the transition between solidification modes in austenitic stainless steel weld metal. J Weld World, 56, 2–14.

Vekeman, J., Huysmans, S., & De Bruycker, E. (2014). Weldability assessment and high temperature properties of advanced creep resisting austenitic steel DMV304HCu. J Weld World, 58, 873–882.

Villafuerte, J. C., & Kerr, H. W. (1990). Grain structures in gas tungsten-arc welds of austenitic stainless steels with ferrite primary phase. J Metall Trans A, 21, 979–986.

Viswanathan, R., Henry, J. F., Tanzosh, J., et al. (2005). U.S. program on materials technology for ultra-supercritical coal power plants. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance, 14, 281–292.

Yang, H., Peng, F., Miao, X., et al. (2006). Investigation of the aging behavior on boiler steel tube Super304H. J Press Equip Syst, 4, 96–99.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their sincere thanks to M/s Mailam India Ltd, Pondicherry, India for providing financial assistance to carry out this research work through the Mailam India Research (MIR) Fellowship, M/s Salzgitter Mannesmann Stainless Tubes Italia Srl of Italy for supplying the Super 304H tubes required to carry out this work and The Director, Naval Materials Research Laboratory, Ambernath, Mumbai for providing the facility to carry out hot tensile testing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Vinoth Kumar, M., Balasubramanian, V. & Gourav Rao, A. Effect of filler addition on solidification behaviour and hot tensile properties of GTA-welded tube joints of Super 304H austenitic stainless steel. Int J Mech Mater Eng 10, 25 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40712-015-0051-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40712-015-0051-x