Abstract

Background

Dietary supplementation with a fucoidan-rich Ascophyllum nodosum extract (ANE), possessing an in vitro anti-Salmonella Typhimurium activity could be a promising on-farm strategy to control Salmonella infection in pigs. The objectives of this study were to: 1) evaluate the anti-S. Typhimurium activity of ANE (containing 46.6% fucoidan, 18.6% laminarin, 10.7% mannitol, 4.6% alginate) in vitro, and; 2) compare the effects of dietary supplementation with ANE and Zinc oxide (ZnO) on growth performance, Salmonella shedding and selected gut parameters in naturally infected pigs. This was established post-weaning (newly weaned pig experiment) and following regrou** of post-weaned pigs and experimental re-infection with S. Typhimurium (challenge experiment).

Results

In the in vitro assay, increasing ANE concentrations led to a linear reduction in S. Typhimurium counts (P < 0.05). In the newly weaned pig experiment (12 replicates/treatment), high ANE supplementation increased gain to feed ratio, similar to ZnO supplementation, and reduced faecal Salmonella counts on d 21 compared to the low ANE and control groups (P < 0.05). The challenge experiment included thirty-six pigs from the previous experiment that remained on their original dietary treatments (control and high ANE groups with the latter being renamed to ANE group) apart from the ZnO group which transitioned onto a control diet on d 21 (ZnO-residual group). These dietary treatments had no effect on performance, faecal scores, Salmonella shedding or colonic and caecal Salmonella counts (P > 0.05). ANE supplementation decreased the Enterobacteriaceae counts compared to the control. Enterobacteriaceae counts were also reduced in the ZnO-residual group compared to the control (P < 0.05). ANE supplementation decreased the expression of interleukin 22 and transforming growth factor beta 1 in the ileum compared to the control (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

ANE supplementation was associated with some beneficial changes in the composition of the colonic microbiota, Salmonella shedding, and the expression of inflammatory genes associated with persistent Salmonella infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Weaning is a critical period in pig production as the associated nutritional, emotional, social and environmental stressors reduce feed intake and increase gastrointestinal dysfunction and dysbiosis [1,2,3,4]. These changes result in reduced growth performance and increased susceptibility to pathogens including Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotypes. Previous studies have demonstrated that weaned pigs disseminate and maintain Salmonella infection at farm level [5,6,7,8]. Movement to grower and finisher houses, handling and re-grou** are additional stress factors that could increase Salmonella shedding and susceptibility to infection resulting in further pig-to-pig and contaminated environment-to-pig transmission on farms [6, 9]. Dietary supplementation with ZnO at pharmacological doses (2000–3000 mg/kg feed) during the immediate post-weaning period is a common practice to alleviate the negative impact of weaning on pig performance [10] and gastrointestinal functionality and health [11,12, A. nodosum was harvested in February 2019 (Quality Sea Veg Ltd., Burtonport, Co. Donegal, Ireland). Whole seaweed biomass was oven-dried at 50 °C for 9 d and milled to a 1 mm particle size (Christy and Norris Hammer Mill, Chelmsford, UK) and stored at room temperature. The ANE extract was obtained using a hydrothermal-assisted extraction method using the optimal conditions for best fucoidan yield (120 °C, 62.1 min, 30 mL 0.1 mol/L HCl/g seaweed) as described previously [34]. The ANE composition as % w/w dry matter was as follows: 46.6% fucoidan, 18.6% laminarin, 10.7% mannitol, 4.6% alginate, 4.5% protein and 0.75% ash. The ANE was stored at − 20 °C. The concentration of fucoidan was estimated according to the method described by Usov et al. [35], with modifications as described by Garcia-Vaquero et al. [34]. The concentration of laminarin and mannitol was determined using standard kits (Megazyme Ltd., Bray, Co. Wicklow, Ireland) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of alginate was estimated according to the method described by Truus et al. [36]. The ash content was determined after ignition of a weighed sample in a muffle furnace (Nabertherm GmbH, Lilienthal, Germany) at 550 °C for 6 h according to the AOAC.942.05 [37]. The nitrogen content was determined using the LECO FP 528 instrument (Leco Instruments UK Ltd., Cheshire, UK) according to the AOAC.990.03 [37]. The conversion factor 4.17 was used to calculate protein content, as described for brown macroalgae [38]. The revival and culture of the S. Typhimurium phage type (PT) 12 and Bifidobacterium thermophilum (DSMZ 20210) and the subsequent pure culture growth assays were carried out as described by Venardou et al. [39]. Briefly, S. Typhimurium and B. thermophilum were revived from cryoprotective beads (TS/71-MX, Protect Multi-purpose, Technical Service Consultants Ltd., Lancashire, UK) and sub-cultured following standard procedures to obtain 24 h cultures. The pure culture growth assays were carried out in 96-well microtiter plates (CELLSTAR, Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmünster, Austria). ANE was diluted appropriately in 10% de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe broth (MRS, Oxoid Ltd., Hampshire, UK) and 10% Tryptone soya broth (TSB, Oxoid Ltd., Hampshire, UK) to obtain a final concentration of 5, 4, 3, 2 and 1 mg/mL prior to the assay. S. Typhimurium and B. thermophilum were diluted in 10% TSB and MRS, respectively, to obtain an inoculum of 106–107 CFU (Colony-forming unit)/mL with initial bacterial enumeration performed each time. Equal quantities of each ANE concentration and inoculum were transferred to duplicate wells and control wells containing no ANE were also included. To evaluate the sterility, blank wells containing equal quantities of 10% medium and each ANE concentration were included. Plates were agitated gently for thorough mixing and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h aerobically for S. Typhimurium or anaerobically for B. thermophilum. After incubation, a 10-fold serial dilution (10−1–10−8) followed by spread plating onto Tryptone soya agar (Oxoid Ltd., Hampshire, UK) for S. Typhimurium and de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe agar (Oxoid Ltd., Hampshire, UK) for B. thermophilum were used to determine both the bacterial viability and counts at the increasing ANE concentrations. Plates were incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 24 h for S. Typhimurium and anaerobically at 37 °C for 48 h for B. thermophilum. Anaerobic conditions were established within sealed containers using AnaeroGen 2.5 and 3.5 L sachets (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The dilution resulting in 5–50 colonies was selected for the calculation of CFU/mL using the formula CFU/mL = Average colony number × 50 × dilution factor. The bacterial counts were logarithmically transformed (logCFU/mL) for the subsequent statistical analysis. Zero counts at the neat dilution (100) were assigned the arbitrary value of 1.30 logCFU/mL which was considered the minimum detection limit using spread plating [40]. All experiments were carried out with technical replicates on three independent occasions (3 biological replicates). The experiment had a randomised complete block design and consisted of the following dietary treatments: (T1) basal diet (control); (T2) basal diet + 3.1 g ZnO (pharmacological dose)/kg feed (ZnO); (T3) basal diet + 2 g ANE/kg feed (low ANE) and (T4) basal diet + 4 g ANE/kg feed (high ANE). The ANE inclusion levels were selected based on the in vitro anti-S. Typhimurium activity of the 2 and 4 mg/mL ANE. In particular, the concentration of 2 mg/mL was the lowest ANE concentration with some anti-S. Typhimurium activity, whereas the concentration of 4 mg/mL ANE, along with 5 mg/mL, had the strongest effect. Ninety-six healthy pigs [progeny of meat-line boars × (Large White × Landrace sows)] with average weight 8.6 (standard deviation (SD) 1.12) kg were sourced from a commercial pig farm at weaning (28 days of age) and were penned in groups of two. At the time of weaning, the Salmonella seroprevalence for the herd in the farm of origin was estimated at 46.7% (weighted average of previous three months data). The pigs were blocked based on weaning weight, litter of origin and sex and within each block assigned to one of the four treatments (12 replicates/treatment). The basal diet contained 10.6 MJ/kg net energy and 14.0 g/kg standard ileal digestible lysine. All amino acid requirements were met relative to lysine [41]. The ingredient composition and the analysed and calculated chemical composition of the diet are presented in Table 1. All treatment diets were milled on site and fed in meal form for 21 d. The ZnO (Cargill, Naas, Co. Kildare, Ireland) was included at 3100 mg/kg feed and contained 80% Zn, resulting in an inclusion level of 2500 mg Zn per kg feed.

The pigs were housed in fully slatted pens (1.7 m × 1.2 m) and weighed at the beginning of the experiment (d 0) and on d 7, 14 and 21. The ambient environmental temperature within the house was thermostatically controlled at 30 °C for the first 7 d and reduced by 2 °C per week for the remainder of the experiment. The humidity was maintained at 65%. Feed and water were available ad libitum from four-space feeders and nipple drinkers; precaution was taken to avoid feed wastage. Faecal scores (FS) were recorded twice daily in the individual pens by the same operator on a scale ranging from 1 to 5. The scoring system was as follows: 1 = hard, firm faeces; 2 = slightly soft faeces; 3 = soft, partially formed faeces; 4 = loose, semi-liquid faeces; and 5 = watery, mucous like faeces [43]. Faecal samples were collected after natural defaecation into sterile containers (Sarstedt AG & Co. KG, Nümbrecht, Germany) on arrival on d 0 from 19 pigs to determine the Salmonella status of the herd. Rectal faecal samples were collected into sterile containers from the same pig in each pen (n = 48 pigs) on d 14 and 21. Samples were obtained by natural defaecation with rectal stimulation employed only if necessary and solely on d 21. All faecal samples were immediately stored at − 20 °C. On d 21, ZnO supplementation ceased and one pig from each pen from (T1), (T2) and (T4) of the newly weaned pig experiment (n = 36, 12 replicates/treatment) proceeded to the challenge experiment. The pigs from (T1) and (T4) were kept on their original diets as described in the newly weaned pig experiment with (T4) being renamed as ANE, whereas (T2) was renamed as ZnO-residual, whereby the animals were fed a basal diet upon ZnO removal. Between d 21 and 25, all pigs were on their respective diet, however, performance data was collected after the initiation of the challenge experiment on d 25. The challenge experiment had a randomised complete block design. The thirty-six pigs with an average weight of 18.3 (2.44 SD) kg on d 25 were blocked on weight basis and penned in pairs. The pigs were weighed at the beginning (d 25) and end (d 34) of the experiment. The housing and animal management were as described in the newly weaned pig experiment apart from the ambient environmental temperature that was kept at 25 °C during the nine-day experimental period in each house and the FS that was recorded once daily in the individual pens. On d 25, each animal was manually restrained and orally challenged with 5 mL of a S. Typhimurium culture (infectious dose ≈ 4 × 107 CFU) using a syringe (no needle attached). Rectal faecal samples were collected in sterile containers from all pigs on d 25 (prior to S. Typhimurium infection), 27 and 34 for Salmonella quantification and immediately stored at − 20 °C. Samples were obtained following natural defaecation or if necessary with rectal stimulation. On d 34, all 36 pigs were euthanised by pentobarbitone sodium (Euthatal Solution, 200 mg/mL; Merial Animal Health, Essex, UK) overdose (1 mL/kg body weight injected into the cranial vena cava). Euthanasia was completed by a competent person in a separate room away from sight and sound of the other pigs. The entire intestinal tract was immediately removed. Colonic and caecal digesta were collected in sterile containers, snap frozen on dry ice and stored at − 20 °C for bacterial quantification using quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (QPCR). Additionally, 1 cm2 sections from the ileum (15 cm from ileocaecal junction) and colon were removed, emptied by dissection along the mesentery and rinsed using sterile phosphate buffered saline (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The tissue sections were stripped of the overlying smooth muscle before overnight storage in 5 mL RNAlater® solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 4 °C. The RNAlater® was removed before storing the samples at − 80 °C. These ileal and colonic tissue samples were used for gene expression analysis. The feed was milled through a 1-mm screen (Christy and Norris Hammer Mill, Chelmsford, England). The dry matter content was determined after drying overnight at 104 °C. Ash content was determined after ignition of a weighted sample in a muffle furnace at 550 °C for 6 h according to the AOAC.942.05 [37]. The gross energy content was determined using an adiabatic bomb calorimeter (Parr Instruments, Moline, IL, USA). Crude protein content was determined by measuring the nitrogen content of the feed samples using the LECO FP 528 instrument and the conversion factor of 6.25 according to the AOAC.990.03 [37]. The neutral detergent fibre content was determined according to the method of Van Soest et al. [44] and the crude fibre content according to the AOAC method [37]. The crude fat content of the diets was determined using light petroleum ether and Soxtec instrumentation (Tecator, Sweden) according to the AOAC.920.39 [37]. Faecal samples from d 0 were screened for the presence or absence of Salmonella in accordance with the protocol of the International Organisation for Standardization (ISO) 6579–1:2017. Salmonella seroty**, which involved agglutination tests with hyperimmune antisera specific for a range of somatic (O) and flagellar (H) antigens and comparison with the White-Kauffmann-Le Minor scheme [45], was also performed on Salmonella positive samples in accordance with ISO protocol 6579–3:2014. Isolates with a phenotypic partial seroty** were further analysed using a multiplex QPCR for differentiating S. Typhimurium and its monophasic variant S. 4,[5],12:i:- as described previously [46]. Microbial genomic DNA was extracted from faecal, colonic and caecal samples using QIAamp® PowerFecal® Pro DNA Kit (Qiagen, West Sussex, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA quantity and quality were evaluated using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The domain-, function-, family- or genus-specific primers for the selected bacterial groups were available in the literature (with the exception of Salmonella enterica) and are provided in Table 2. The 16S rRNA gene was targeted for most bacterial groups except for Salmonella where the hilA gene, the transcriptional regulator of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 was selected [53] and also the butyrate-producing bacteria where the Butyryl-CoA:acetate CoA-transferase (B-CoA) gene associated with this function was selected [48, 51]. Primers were designed using two tools, Primer3 (https://primer3.org/) for larger amplicons (> 150 bp) and Primer Express™ (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) for smaller amplicons optimised for QPCR (< 125 bp), and their specificity was verified using Primer Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (Primer-BLAST), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/index.cgi.

The quantification of the selected bacterial groups using QPCR and the preparation of specific plasmids (total bacteria, Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp., Prevotella spp., Enterobacteriaceae) to obtain the standard curves was carried out as described by Venardou et al. [39]. Additionally, plasmids containing the hilA and B-CoA genes were prepared from genomic DNA of S. Typhimurium extracted from pure cultures (DNeasy® Blood & Tissue kit, Qiagen, West Sussex, UK) and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (DSMZ 17677) purchased from Leibniz Institute DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (Braunschweig, Germany) respectively. The primers and genomic locations of all targeted genes that were incorporated into plasmids are outlined in Table S1 (Additional file 1). The plasmids were quantified spectrophotometrically and the copy number/μL was determined using an online tool which employs the formula mol/g × molecules/mol = molecules/g using Avogadro’s constant, 6.022 × 1023 molecules/mole (http://cels.uri.edu/gsc/cndna.html). The QPCR reaction (20 μL) included 3 μL template DNA, 1 μL or 2 μL (for B-CoA) of each primer (10 μmol/L), 5 μL or 3 μL (for B-CoA) nuclease-free water and 10 μL of GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). All QPCR reactions were performed in duplicate on the 7500 ABI Prism Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the following cycling conditions; a denaturation step of 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. Dissociation curves were generated to confirm the specificity of the amplicons. The efficiency of each QPCR assay was established from the slope of the curve derived from plotting the Cycle threshold (Ct) obtained from 5-fold serial dilutions of the plasmid against their arbitrary quantities. Only assays exhibiting 90–110% efficiency and generating specific products were used in this study. Bacterial counts were determined from the standard curve derived from the mean Ct value and the log transformed gene copy number of the plasmid and expressed as Log transformed gene copy number per gram of faeces or digesta (logGCN/g faeces or digesta). Total RNA was extracted from ileal and colonic tissue using TRI Reagent® (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and purified using GenElute™ Mammalian Total RNA Miniprep Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and a DNase removal step (On-Column DNase I Digestion Set, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The quantity and purity (260/280 nm absorbance ratio ≥ 2.0) of the total RNA was determined using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer. The complimentary DNA (cDNA) was synthesised from 2 μg total RNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The total reaction volume (20 μL) was adjusted to 400 μL using nuclease-free water. The QPCR reaction mix (20 μL) contained 10 μL GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix, 1.2 μL forward and reverse primers (5 μmol/L), 3.8 μLnuclease-free water and 5 μL cDNA. All QPCR reactions were carried out in duplicate on the 7500 ABI Prism Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the following cycling conditions; a denaturation step of 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. All primers were designed using the Primer Express™ Software and synthesised by MWG Biotech UK Ltd. (Milton Keynes, UK) and are presented in Table 3. The sequences of the forward and reverse primers have been described and validated previously for porcine gastrointestinal tissues [29, 60, 61] except for IL7, CCL20, TP53, STAT3, CHRM1, NOX1 and DUOX2 genes for which the primer pairs were newly designed, and their specificity was verified in silico using Primer-BLAST. Dissociation curves were generated to confirm the specificity of the resulting PCR products. The efficiency of each QPCR reaction was established by plotting the Ct derived from 4-fold serial dilutions of cDNA against their arbitrary quantities. Assays exhibiting 90–110% efficiency and single products were solely used in this study. Normalised relative quantities were obtained using the qbase™ PLUS software (Biogazelle, Ghent, Belgium) from two stable housekee** reference genes, GAPDH and PPIA for the ileum and B2M and PPIA for the colon. These genes were selected as reference genes due to their lowest stability M value (< 1.5) generated by the geNorm application.

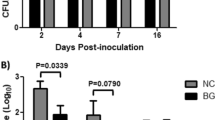

All data was initially checked for normality using PROC UNIVARIATE procedure of Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The bacterial counts from the pure culture growth assays were analysed using PROC GLM procedure for the presence of linear and quadratic effects of ANE concentration. The biological replicate was the experimental unit. The LSMEANS statement was additionally used to calculate the least-square mean values and the standard error of the means (SEM). The performance data from the newly weaned pig experiment, FS data from both experiments and Salmonella shedding data from the challenge experiment were analysed by repeated measures analysis using PROC MIXED procedure of SAS [62]. The model included the fixed effects of treatment and time and their associated interaction. For the performance data, the initial weight was used as a covariate. Salmonella shedding data from the newly weaned pig experiment, performance data from the challenge experiment, bacterial populations data and gene expression data were analysed using PROC GLM procedure of SAS. The Bonferroni adjustment was used in the analysis of the gene expression data. The model assessed the effect of treatment with the experimental unit being the pen for the performance data and the animal within the pen for the bacterial populations and gene expression data. For the performance data, the body weight on d 25 was used as a covariate. Probability values of < 0.05 denote statistical significance. Results are presented as least-square mean values ± SEM. The effects of ANE on the counts of S. Typhimurium and B. thermophilum were evaluated in pure culture growth assays and presented in Fig. 1. There was a linear decrease in the counts of S. Typhimurium (≤ 7.6 logCFU/mL reduction) and B. thermophilum (≤ 1.4 logCFU/mL reduction) in response to the increasing ANE concentrations (P < 0.05). However, the antibacterial effect of ANE was more pronounced for S. Typhimurium than for B. thermophilum (7.6 vs. 1.4 logCFU/mL reduction, respectively).

All 19 pigs sampled on d 0 were identified as Salmonella-positive using QPCR with average counts of 7.41 (SD 0.308) logGCN/g faeces. Salmonella presence was additionally confirmed using standard ISO protocols and the prevalent serotypes were identified. 11 out of the 19 pigs were Salmonella positive with S. Enteritidis being the predominant serotype (8 out of 11 pigs) followed by the monophasic variant of S. Typhimurium, S. 4,[5],12:i:- (3 out of 11 pigs). The effects of ZnO and the two ANE concentrations on final body weight (BW), average daily gain (ADG), average daily feed intake (ADFI) and gain to feed ratio (G:F) are presented in Table 4. There was no time × treatment interaction on final BW, ADG, ADFI and G:F (P > 0.05). However, during the overall 21-day experimental period, dietary supplementation with ZnO increased final BW, ADG and ADFI compared to all other treatments (P < 0.05), whereas none of the ANE concentrations had an effect on these parameters (P > 0.05). Both ZnO and high ANE supplementation increased G:F compared to the other treatments (P < 0.05).

The effects of ZnO and the two ANE concentrations on FS are presented in Fig. 2. There was no time × treatment interaction on FS (P > 0.05). Overall, dietary supplementation with ZnO reduced FS compared to all other treatments during the 21-day experimental period [2.83 (ZnO) vs. 3.04 (control), 3.11 (low ANE) and 3.11 (high ANE) ± 0.036, P < 0.05]. None of the ANE concentrations had an effect on FS (P > 0.05).

Effect of dietary treatments on faecal consistency during the first 21 d post-weaning. The scoring system was from 1 to 5: (1) hard, firm faeces; (2) slightly soft faeces; (3) soft, partially formed faeces; (4) loose, semi-liquid faeces; (5) watery, mucous like faeces [43]. Data are expressed as least-square mean values ± SEM represented in vertical bars. A total of 12 replicates were used per dietary treatment (replicate = pen). ANE, Ascophyllum nodosum extract; ZnO, Zinc oxide The effects of ZnO and ANE concentrations on Salmonella faecal shedding are presented in Table 5. On d 14, there was no effect of the dietary treatments on Salmonella counts in the faeces (P > 0.05). However, on d 21, dietary supplementation with high ANE reduced Salmonella counts in the faeces compared to the control and low ANE group (P < 0.05).

The effect of ANE and the residual effect of ZnO on final BW, ADG, ADFI and G:F are presented in Table 6. There was no effect of the dietary treatments on final BW, ADG, ADFI and G:F during the 9-day period (P > 0.05). There were no treatment and time effects and time × treatment interaction on FS (P > 0.05, data not shown).

The effect of ANE and the residual effect of ZnO on Salmonella faecal shedding following the experimental re-infection with S. Typhimurium are presented in Table 7. The dietary treatments had no effect on Salmonella counts in the faeces on any of the days tested (P > 0.05). There was a time effect on Salmonella shedding. Salmonella counts were lower in the faeces on d 25 compared to d 34 (7.13 logGCN/g faeces vs. 7.35 logGCN/g faeces ± 0.150, P < 0.05).

The effect of ANE and the residual effect of ZnO on Salmonella counts in colonic and caecal digesta and on selected colonic bacterial populations of pigs on d 34 are presented in Table 8. There was no effect of the dietary treatments on Salmonella counts in colonic and caecal digesta (P > 0.05). Enterobacteriaceae counts were decreased in the ANE-supplemented and ZnO-residual groups compared to the control group (P < 0.05). Dietary supplementation with ANE increased Bifidobacterium spp. counts compared to the ZnO-residual group (P < 0.05), but not compared to the control group (P = 0.112). There was no effect of the dietary treatments on the counts of total bacteria, Lactobacillus spp., butyrate-producing bacteria (B-CoA) and Prevotella spp. (P > 0.05).

The effect of ANE and the residual effect of ZnO on the expression of selected genes in the ileum and colon of pigs are presented in Table 9. In the ileum, dietary supplementation with ANE decreased the expression of Interleukin 22 (IL22) and Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFB1) compared to the control (P < 0.05). In the colon, dietary supplementation with ANE decreased the expression of C-C motif chemokine ligand 20 (CCL20) compared to the ZnO-residual group (P < 0.05).

In this study, the fucoidan-rich A. nodosum extract (ANE) had a strong concentration-dependent anti-S. Typhimurium activity in vitro and was therefore further explored in two in vivo experiments. In a ‘newly weaned pig’ experimental model with naturally infected pigs, high ANE supplementation reduced Salmonella counts in the faeces on d 21 post-weaning and increased G:F. In a ‘challenge’ experiment, none of the dietary treatments had an effect on performance or Salmonella counts in the faeces or digesta. Nevertheless, ANE supplementation reduced the Enterobacteriaceae counts in the colon compared to the control group, with no effect on the other bacterial populations measured. Additionally, the expression of IL22 and TGFB1 was decreased in the ileum of the ANE-supplemented pigs compared to the control group. These results indicate that ANE may be a promising dietary supplement with which to counteract the negative impact of Salmonella infection on the gastrointestinal microbiota and inflammation in pigs and could be usefully combined with other husbandry measures. An additional finding of this study was the reduced Enterobacteriaceae counts in the ZnO-residual group indicating that short-term ZnO supplementation could have longer lasting residual effects on the gastrointestinal microbiota. In the pure culture growth assay, the inclusion of ANE led to a significant and concentration-dependent reduction in the counts of the pathogen S. Typhimurium. ANE also reduced the counts of the commensal B. thermophilum, though to a lesser extent. While it is not possible to definitively identify which is the bioactive component of the ANE extract, it consisted predominantly of fucoidan (~ 47%), with other polysaccharides including laminarin, mannitol and alginate present at lower concentrations (18.6%, 10.7% and 4.6%, respectively). Depolymerised fucoidans are thought to exert antibacterial activity by disrupting the integrity and permeability of the bacterial cell membrane resulting in cell leakage and death and/or by nutrient trap** [18, 19, 63]. We hypothesise that a mixture of low molecular weight fucoidans with anti-Salmonella activity are present in the ANE as a result of fucoidan depolymerisation due to the HCl and high temperature of the hydrothermal-assisted extraction methodology [32, 64]. The immediate post-weaning period in commercial pig production systems is characterised by reduced growth, reduced feed intake and an increased incidence of diarrhoea [1, 2]. Salmonella infection and shedding in pigs has been associated with similar suboptimal measures of performance [65,66,67,68]. In the newly weaned pig experiment, dietary supplementation with high ANE improved G:F and reduced faecal Salmonella counts. While the ANE displayed a strong anti-S. Typhimurium activity during its in vitro evaluation in the current study, the reduction in Salmonella counts in vivo was not of the same magnitude. This may be due in part to the fact that the depolymerised fractions of fucoidan, previously hypothesised to exert the antibacterial activity, may have increased availability as a substrate for fermentation to different members of the gastrointestinal microbiota as observed elsewhere [20, 69] which might explain the reduced anti-S. Typhimurium activity of ANE in vivo. The influence of ANE supplementation was further explored in pigs during the grower phase. At the start of this phase, the pigs were moved and regrouped and received an experimental Salmonella infection. Even though a slight increase in Salmonella shedding was observed, it appears that the re-infection with S. Typhimurium did not have a major impact on either the established Salmonella population or Salmonella shedding. Despite the reduced Salmonella counts in the faeces of ANE-supplemented pigs in the newly weaned pig experiment, this observation was not evident in the challenge experiment, either in the faeces collected at different time points or in the colonic and caecal digesta collected at the end of the experiment. In a previous study, dietary supplementation with a fucoidan-rich seaweed extract reduced the faecal, colonic and caecal Salmonella counts in grower pigs experimentally infected with S. Typhimurium [29]. However, in that study of Bouwhuis et al. [29], the supplementation of the seaweed extract preceded the S. Typhimurium infection in pigs, whereas in the current study the pigs had a natural Salmonella infection with two different serotypes (S.Enteritidis and S. 4,[5],12:i:-) prior to the ANE supplementation. These results suggest that early ANE supplementation might have been more effective as a preventative dietary intervention for Salmonella infection in pigs. In addition, there may be variation in the antibacterial activity of ANE against different Salmonella serotypes. Nevertheless, ANE supplementation was associated with reduced Enterobacteriaceae counts in the colonic digesta with no negative impact on the counts of the other bacterial populations measured, namely total bacteria, Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp., Prevotella spp. and butyrate-producing bacteria. This finding suggests that ANE has antibacterial activity against various members within the Enterobacteriaceae family, thus, limiting the available fucoidan that could target the Salmonella subpopulation. The lower Enterobacteriaceae counts could be indicative of a healthier composition of the colonic microbiota in the ANE-supplemented pigs, as this bacterial family is considered a marker of dysbiosis and a predisposing factor for intestinal disease post-weaning [3, 70, 71]. Salmonella infection in pigs is accompanied by intestinal inflammation that has a negative impact on the composition of the residing microbiota, thus, facilitating pathogen colonisation and shedding [68, 72]. Dietary supplementation with ANE altered the mucosal immune response in the ileum by reducing the expression of IL22 and TGFB1. Several murine studies have demonstrated that elevated IL22 expression and protein synthesis are associated with increased susceptibility to Salmonella colonisation and persistent infection in the gastrointestinal tract due to the IL22-induced suppression of commensal bacteria via the secretion of antimicrobial proteins (lipocalin-1, S100A8, S100A9, Reg3β, Reg3γ) [73,74,75]. IL22 may also contribute to Salmonella colonisation and the carrier state in pigs as its production was increased following experimental Salmonella infection [76]. The reduction in IL22 expression may be linked to the reduced TGFB1 expression, as TGFβ1 promotes the differentiation of Th17 cells that produce IL22 [77, 78]. Previous studies have characterised the inhibitory effect of fucoidan on TGFβ1 production and activity by interfering with TGFβ1 activation and binding to its receptor [79, 80]. Furthermore, TGFB1 gene expression was elevated in mice with chronic S. Typhimurium colonisation [81], whereas reduced TGFβ1 presence decreased S. Typhimurium counts in both the spleen and liver, highlighting its potential role in pathogen persistence [82]. Thus, ANE supplementation may have the potential to decrease the immune responses that facilitate Salmonella colonisation and persistence, as evidenced by the reduced IL22 and TGFB1 expression. Dietary supplementation with the pharmacological dose of ZnO during the first 21 d post-weaning, improved growth performance and faecal consistency similar to previous weaned pig studies with [83, 88] and AMR [14, 16] within the Escherichia coli population as indicated in previous studies. The residual effect of ZnO on the Enterobacteriaceae counts observed in the current study merits further research concerning the prevalence of Zn resistance and AMR within this family following ZnO removal, particularly in countries where ZnO supplementation is still applicable during the weaning transition. We hypothesise that the observed beneficial effects on Salmonella shedding, the composition of the colonic microbiota and the expression of inflammatory genes in the ileum of the ANE-supplemented pigs were associated with a mixture of low molecular weight fucoidans, as it was the principal component (~ 47%) in this extract. Nevertheless, this should be confirmed by future experiments with purified fucoidan fractions of ANE. Furthermore, the potential contributing role of other components of ANE such as laminarin (~ 19% in ANE) on the observed bioactivities should also be explored. In previous studies, laminarin supplementation led to reduced Enterobacteriaceae counts and expression of inflammatory markers in the gastrointestinal tract of weaned pigs [89,90,91]. This polysaccharide was also present in moderate amount in the A. nodosum extract supplemented to the pigs in the Salmonella study of Bouwhuis et al. [29]. In conclusion, the anti-Salmonella activity of ANE was established in vitro prior to its in vivo evaluation in two consecutive experiments in naturally infected weaned pigs. In the newly weaned pig experiment, high ANE supplementation improved G:F post-weaning while also reducing faecal Salmonella counts. In the challenge experiment, a slight increase in Salmonella shedding was observed in response to pig transfer to the grower houses, regrou** and experimental re-infection with S. Typhimurium. ANE supplementation had no effect on Salmonella counts; nevertheless, it reduced Enterobacteriaceae counts, as well as the expression of the inflammatory IL22 and TGFB1 which are associated with colonisation and persistent Salmonella infection. Thus, the use of ANE as a dietary supplement merits further exploration regarding its potential to prevent Salmonella colonisation and persistence in Salmonella-free pigs and to alleviate the gastrointestinal dysfunction in newly weaned pigs. In this study, a potential long-term residual effect of ZnO on the gastrointestinal tract was indicated by the reduced Enterobacteriaceae counts that should be further investigated regarding its implications on pig health.Materials and methods

Ascophyllum nodosum extract (ANE) preparation and chemical composition analyses

In vitro screening of ANE antibacterial activity

Newly weaned pig experiment (d 0–21)

Experimental design and diets

Housing and animal management

Sample collection for Salmonella presence and quantification

Challenge experiment (d 25–34)

Experimental design and diets

Housing and animal management

S. Typhimurium experimental infection

Sample collection

Feed analyses

Salmonella isolation and seroty**

Quantification of selected bacterial groups using QPCR

DNA extraction

Bacterial primers

Plasmid preparation and QPCR for absolute quantification

Gene expression

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

QPCR for relative quantification

Statistical analysis

Results

In vitro effects of ANE on S. Typhimurium and B. thermophilum growth

Salmonella presence and isolated serotypes in pigs on d 0

Newly weaned pig experiment (d 0–21)

Pig performance and faecal consistency

Salmonella faecal shedding

Challenge experiment (d 25–34)

Pig performance and faecal consistency

Salmonella faecal shedding

Enumeration of Salmonella in colonic and caecal digesta and selected bacterial populations in the colonic digesta

Gene expression in ileum and colon

Discussion

Conclusion

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and/or analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADFI:

-

Average daily feed intake

- ADG:

-

Average daily gain

- AMR:

-

Antimicrobial resistance

- ANE:

-

Ascophyllum nodosum extract

- B2M:

-

Beta-2-microglobulin

- B-CoA:

-

Butyryl-CoA:acetate CoA-transferase

- bp:

-

Base pairs

- BW:

-

Body weight

- CCL20:

-

C-C motif chemokine ligand 20

- cDNA:

-

Complimentary DNA

- CFU:

-

Colony-forming unity

- CHRM1:

-

Cholinergic receptor muscarinic 1

- Ct:

-

Cycle threshold

- CXCL8:

-

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8

- DUOX2:

-

Dual oxidase 2

- FOXP3:

-

Forkhead box P3

- FS:

-

Faecal scores

- GAPDH:

-

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GCN:

-

Gene copy number

- G:F:

-

Gain to feed ratio

- IFNG:

-

Interferon gamma

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- ISO:

-

International Organisation for Standardization

- MRS:

-

de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe broth

- MUC2:

-

Mucin 2

- NOX1:

-

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase 1

- PPIA:

-

Peptidylprolyl isomerase A

- QPCR:

-

Quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction

- SAS:

-

Statistical Analysis Software

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SEM:

-

Standard error of the means

- STAT3:

-

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- TGFB1:

-

Transforming growth factor beta 1

- TJP1/ZO-1:

-

Tight junction protein 1/Zona occludens 1

- TLR4:

-

Toll-like receptor 4

- Tm:

-

Melting temperature

- TNF:

-

Tumour necrosis factor

- TP53:

-

Tumour protein p53

- TSB:

-

Tryptone soya broth

- ZnO:

-

Zinc oxide

References

Pluske JR, Hampson DJ, Williams IH. Factors influencing the structure and function of the small intestine in the weaned pig: a review. Livest Prod Sci. 1997;51(1):215–36.

Heo JM, Opapeju FO, Pluske JR, Kim JC, Hampson DJ, Nyachoti CM. Gastrointestinal health and function in weaned pigs: a review of feeding strategies to control post-weaning diarrhoea without using in-feed antimicrobial compounds. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2013;97(2):207–37.

Gresse R, Chaucheyras-Durand F, Fleury MA, Van de Wiele T, Forano E, Blanquet-Diot S. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in postweaning piglets: understanding the keys to health. Trends Microbiol. 2017;25(10):851–73.

Moeser AJ, Pohl CS, Rajput M. Weaning stress and gastrointestinal barrier development: implications for lifelong gut health in pigs. Anim Nutr. 2017;3:313–21.

Kranker S, Alban L, Boes J, Dahl J. Longitudinal study of Salmonella enterica aerotype typhimurium infection in three Danish farrow-to-finish swine herds. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(6):2282–8.

Nollet N, Houf K, Dewulf J, Duchateau L, De Zutter L, De Kruif A, et al. Distribution of Salmonella strains in farrow-to-finish pig herds: a longitudinal study. J Food Prot. 2005;68(10):2012–21.

Weaver T, Valcanis M, Mercoulia K, Sait M, Tuke J, Kiermeier A, et al. Longitudinal study of Salmonella 1,4,[5],12:i:- shedding in five Australian pig herds. Prev Vet Med. 2017;136:19–28.

Casanova-Higes A, Marin-Alcala CM, Andres-Barranco S, Cebollada-Solanas A, Alvarez J, Mainar-Jaime RC. Weaned piglets: another factor to be considered for the control of Salmonella infection in breeding pig farms. Vet Res. 2019;50(1):45.

Callaway TR, Morrow JL, Edrington TS, Genovese KJ, Dowd S, Carroll J, et al. Social stress increases fecal shedding of Salmonella typhimurium by early weaned piglets. Curr Issues Intest Microbiol. 2006;7(2):65–71.

Sales J. Effects of pharmacological concentrations of dietary zinc oxide on growth of post-weaning pigs: a meta-analysis. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2013;152(3):343–9.

Starke IC, Pieper R, Neumann K, Zentek J, Vahjen W. The impact of high dietary zinc oxide on the development of the intestinal microbiota in weaned piglets. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2014;87(2):416–27.

Zhu C, Lv H, Chen Z, Wang L, Wu X, Chen Z, et al. Dietary zinc oxide modulates antioxidant capacity, small intestine development, and jejunal gene expression in weaned piglets. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2017;175(2):331–8.

**a T, Lai W, Han M, Han M, Ma X, Zhang L. Dietary ZnO nanoparticles alters intestinal microbiota and inflammation response in weaned piglets. Oncotarget. 2017;8(39):64878–91.

Bednorz C, Oelgeschlager K, Kinnemann B, Hartmann S, Neumann K, Pieper R, et al. The broader context of antibiotic resistance: zinc feed supplementation of piglets increases the proportion of multi-resistant Escherichia coli in vivo. Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;303(6–7):396–403.

Vahjen W, Pietruszynska D, Starke IC, Zentek J. High dietary zinc supplementation increases the occurrence of tetracycline and sulfonamide resistance genes in the intestine of weaned pigs. Gut Pathog. 2015;7:23.

Ciesinski L, Guenther S, Pieper R, Kalisch M, Bednorz C, Wieler LH. High dietary zinc feeding promotes persistence of multi-resistant E. coli in the swine gut. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(1):e0191660.

Doyle MP, Erickson MC. Opportunities for mitigating pathogen contamination during on-farm food production. Int J Food Microbiol. 2012;152(3):54–74.

Liu M, Liu Y, Cao MJ, Liu GM, Chen Q, Sun L, et al. Antibacterial activity and mechanisms of depolymerized fucoidans isolated from Laminaria japonica. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;172:294–305.

Palanisamy S, Vinosha M, Rajasekar P, Anjali R, Sathiyaraj G, Marudhupandi T, et al. Antibacterial efficacy of a fucoidan fraction (Fu-F2) extracted from Sargassum polycystum. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;125:485–95.

Kong Q, Dong S, Gao J, Jiang C. In vitro fermentation of sulfated polysaccharides from E. prolifera and L. japonica by human fecal microbiota. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;91:867–71.

Chen L, Xu W, Chen D, Chen G, Liu J, Zeng X, et al. Digestibility of sulfated polysaccharide from the brown seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum and its effect on the human gut microbiota in vitro. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;112:1055–61.

Zhang W, Oda T, Yu Q, ** JO. Fucoidan from Macrocystis pyrifera has powerful immune-modulatory effects compared to three other fucoidans. Mar Drugs. 2015;13(3):1084–104.

Borazjani NJ, Tabarsa M, You S, Rezaei M. Purification, molecular properties, structural characterization, and immunomodulatory activities of water soluble polysaccharides from Sargassum angustifolium. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;109:793–802.

Ale MT, Meyer AS. Fucoidans from brown seaweeds: an update on structures, extraction techniques and use of enzymes as tools for structural elucidation. RSC Adv. 2013;3(22):8131–41.

Venardou B, McDonnell MJ, Garcia-Vaquero M, Rajauria G, O’Doherty JV, Sweeney T. In vitro evaluation of the effects of a Laminaria hyperborea extract on commensal and pathogenic bacterial strains frequently isolated from the gastrointestinal tract of weaned piglets. In: British Society of Animal Science Annual Conference 2018. Dublin: British Society of Animal Science; 2018.

Venardou B, McDonnell MJ, Garcia-Vaquero M, Rajauria G, O’Doherty JV, Sweeney T. In vitro effects of seaweed extracts on intestinal commensals and pathogens of weaned piglets. In: Microbes and Mucosal Surfaces Focused Meeting. Dublin, Ireland: Microbiology Society; 2018.

Venardou B, Kiely C, Garcia Vaquero M, Rajauria G, O'Doherty JV, Sweeney T. Antibacterial potential of Ascophyllum nodosum against pathogens of veterinary significance in weaned piglets. In: Association for Veterinary Teaching and Research Work Irish Branch annual meeting. Dunsany: Association for Veterinary Teaching and Research Work Irish Branch; 2019.

Venardou B, Kiely C, Garcia Vaquero M, Rajauria G, O'Doherty JV, Sweeney T. High pressure extraction conditions influence the antibacterial and bifidogenic properties of bioactives from the macroalgal species Laminaria hyperborea. In: Nutrients 2019 – nutritional advances in the prevention and Management of Chronic Disease. Barcelona: Nutrients; 2019.

Bouwhuis MA, McDonnell MJ, Sweeney T, Mukhopadhya A, O'Shea CJ, O'Doherty JV. Seaweed extracts and galacto-oligosaccharides improve intestinal health in pigs following Salmonella typhimurium challenge. Animal. 2017;11(9):1488–96.

MacArtain P, Gill CI, Brooks M, Campbell R, Rowland IR. Nutritional value of edible seaweeds. Nutr Rev. 2007;65(12 Pt 1):535–43.

Fletcher HR, Biller P, Ross AB, Adams JMM. The seasonal variation of fucoidan within three species of brown macroalgae. Algal Res. 2017;22:79–86.

Yuan Y, Macquarrie D. Microwave assisted extraction of sulfated polysaccharides (fucoidan) from Ascophyllum nodosum and its antioxidant activity. Carbohydr Polym. 2015;129:101–7.

Okolie CL, Mason B, Mohan A, Pitts N, Udenigwe CC. The comparative influence of novel extraction technologies on in vitro prebiotic-inducing chemical properties of fucoidan extracts from Ascophyllum nodosum. Food Hydrocoll. 2019;90:462–71.

Garcia-Vaquero M, O'Doherty JV, Tiwari BK, Sweeney T, Rajauria G. Enhancing the extraction of polysaccharides and antioxidants from macroalgae using sequential hydrothermal-assisted extraction followed by ultrasound and thermal technologies. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(8):457.

Usov AI, Smirnova GP, Klochkova NG. Polysaccharides of algae: 55. Polysaccharide composition of several brown algae from Kamchatka. Russ J Bioorganic Chem. 2001;27(6):395–9.

Truus K, Vaher M, Taure I. Algal biomass from Fucus vesiculosus (Phaeophyta): investigation of the mineral and alginate components. Proc Estonian Acad Sci Chem. 2001;50:95–103.

AOAC. Official methods of analysis. 18th ed. AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA; 2005.

Biancarosa I, Espe M, Bruckner CG, Heesch S, Liland N, Waagbø R, et al. Amino acid composition, protein content, and nitrogen-to-protein conversion factors of 21 seaweed species from Norwegian waters. J Appl Phycol. 2017;29(2):1001–9.

Venardou B, O'Doherty JV, McDonnell MJ, Mukhopadhya A, Kiely C, Ryan MT, et al. Evaluation of the in vitro effects of the increasing inclusion levels of yeast beta-glucan, a casein hydrolysate and its 5 kDa retentate on selected bacterial populations and strains commonly found in the gastrointestinal tract of pigs. Food Funct. 2021;12(5):2189–200.

McDonnell MJ, Rivas L, Burgess CM, Fanning S, Duffy G. Inhibition of verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli by antimicrobial peptides caseicin a and B and the factors affecting their antimicrobial activities. Int J Food Microbiol. 2012;153(3):260–8.

National Research Council. Nutrient requirements of swine. 11th revised ed. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. p. 420.

Sauvant D, Perez JM, Tran G. Table of composition and nutritional value of feed materials. Pigs, poultry, cattle, sheep, goats, rabbits, horses, fish. Wageningen: Academic Publishers; 2004.

Walsh AM, Sweeney T, O'Shea CJ, Doyle DN. Doherty JVO. Effect of supplementing varying inclusion levels of laminarin and fucoidan on growth performance, digestibility of diet components, selected faecal microbial populations and volatile fatty acid concentrations in weaned pigs. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2013;183(3–4):151–9.

Van Soest PJ, Robertson JB, Lewis BA. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J Dairy Sci. 1991;74(10):3583–97.

Grimont PAD, Weill FX. Antigenic formulae of the Salmonella Serovars. 9th ed. Paris: Institut Pasteur/World Health Organisation; 2007.

Prendergast DM, Hand D, Niota Ghallchoir E, McCabe E, Fanning S, Griffin M, et al. A multiplex real-time PCR assay for the identification and differentiation of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium and monophasic serovar 4,[5],12:i. Int J Food Microbiol. 2013;166(1):48–53.

Frank DN, St. Amand AL, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. PNAS. 2007;104(34):13780.

Metzler-Zebeli BU, Hooda S, Pieper R, Zijlstra RT, van Kessel AG, Mosenthin R, et al. Nonstarch polysaccharides modulate bacterial microbiota, pathways for butyrate production, and abundance of pathogenic Escherichia coli in the pig gastrointestinal tract. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76(11):3692–701.

Penders J, Vink C, Driessen C, London N, Thijs C, Stobberingh EE. Quantification of Bifidobacterium spp., Escherichia coli and Clostridium difficile in faecal samples of breast-fed and formula-fed infants by real-time PCR. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;243(1):141–7.

Takahashi H, Saito R, Miya S, Tanaka Y, Miyamura N, Kuda T, et al. Development of quantitative real-time PCR for detection and enumeration of Enterobacteriaceae. Int J Food Microbiol. 2017;246:92–7.

Louis P, Flint HJ. Development of a semiquantitative degenerate real-time pcr-based assay for estimation of numbers of butyryl-coenzyme a (CoA) CoA transferase genes in complex bacterial samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(6):2009–12.

Matsuki T, Watanabe K, Fujimoto J, Miyamoto Y, Takada T, Matsumoto K, et al. Development of 16S rRNA-Gene-Targeted Group-specific primers for the detection and identification of predominant Bacteria in human feces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68(11):5445–51.

McCabe EM, Burgess CM, O'Regan E, McGuinness S, Barry T, Fanning S, et al. Development and evaluation of DNA and RNA real-time assays for food analysis using the hilA gene of Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica. Food Microbiol. 2011;28(3):447–56.

Sibartie S, O'Hara AM, Ryan J, Fanning A, O'Mahony J, O'Neill S, et al. Modulation of pathogen-induced CCL20 secretion from HT-29 human intestinal epithelial cells by commensal bacteria. BMC Immunol. 2009;10:54.

Flores MV, Crawford KC, Pullin LM, Hall CJ, Crosier KE, Crosier PS. Dual oxidase in the intestinal epithelium of zebrafish larvae has anti-bacterial properties. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;400(1):164–8.

Burton NA, Schurmann N, Casse O, Steeb AK, Claudi B, Zankl J, et al. Disparate impact of oxidative host defenses determines the fate of Salmonella during systemic infection in mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15(1):72–83.

Huang T, Huang X, Shi B, Wang F, Feng W, Yao M. Regulators of Salmonella-host interaction identified by peripheral blood transcriptome profiling: roles of TGFB1 and TRP53 in intracellular Salmonella replication in pigs. Vet Res. 2018;49(1):121.

Jaslow SL, Gibbs KD, Fricke WF, Wang L, Pittman KJ, Mammel MK, et al. Salmonella activation of STAT3 signaling by SarA effector promotes intracellular replication and production of IL-10. Cell Rep. 2018;23(12):3525–36.

Pohl CS, Lennon EM, Li Y, DeWilde MP, Moeser AJ. S. Typhimurium challenge in juvenile pigs modulates the expression and localization of enteric cholinergic proteins and correlates with mucosal injury and inflammation. Auton Neurosci. 2018;213:51–9.

Ryan MT, O'Shea CJ, Collins CB, O'Doherty JV, Sweeney T. Effects of dietary supplementation with Laminaria hyperborea, Laminaria digitata, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae on the IL-17 pathway in the porcine colon. J Anim Sci. 2012;90(Suppl 4):263–5.

Vigors S, O'Doherty JV, Kelly AK, O'Shea CJ, Sweeney T. The effect of divergence in feed efficiency on the intestinal microbiota and the intestinal immune response in both unchallenged and lipopolysaccharide challenged Ileal and colonic explants. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(2):e0148145.

Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD, Schabenberger O. SAS for Mixed Models. 2nd ed. Cary: SAS Institute; 2006.

Huang CY, Kuo CH, Lee CH. Antibacterial and antioxidant capacities and attenuation of lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes by low-molecular-weight fucoidans prepared from compressional-puffing-pretreated Sargassum Crassifolium. Mar Drugs. 2018;16(1):24.

Yuan Y, Macquarrie DJ. Microwave assisted step-by-step process for the production of fucoidan, alginate sodium, sugars and biochar from Ascophyllum nodosum through a biorefinery concept. Bioresour Technol. 2015;198:819–27.

Balaji R, Wright KJ, Hill CM, Dritz SS, Knoppel EL, Minton JE. Acute phase responses of pigs challenged orally with Salmonella typhimurium1. J Anim Sci. 2000;78(7):1885–91.

Turner JL, Dritz SS, Higgins JJ, Minton JE. Effects of Ascophyllum nodosum extract on growth performance and immune function of young pigs challenged with Salmonella typhimurium1. J Anim Sci. 2002;80(7):1947–53.

Farzan A, Friendship RM. A clinical field trial to evaluate the efficacy of vaccination in controlling Salmonella infection and the association of Salmonella-shedding and weight gain in pigs. Can J Vet Res. 2010;74(4):258–63.

Knetter SM, Bearson SM, Huang TH, Kurkiewicz D, Schroyen M, Nettleton D, et al. Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium-infected pigs with different shedding levels exhibit distinct clinical, peripheral cytokine and transcriptomic immune response phenotypes. Innate Immun. 2015;21(3):227–41.

Hwang PA, Phan NN, Lu WJ, Ngoc Hieu BT, Lin YC. Low-molecular-weight fucoidan and high-stability fucoxanthin from brown seaweed exert prebiotics and anti-inflammatory activities in Caco-2 cells. Food Nutr Res. 2016;60:32033.

Dou S, Gadonna-Widehem P, Rome V, Hamoudi D, Rhazi L, Lakhal L, et al. Characterisation of early-life fecal microbiota in susceptible and healthy pigs to post-weaning diarrhoea. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0169851.

Zeng MY, Inohara N, Nunez G. Mechanisms of inflammation-driven bacterial dysbiosis in the gut. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10(1):18–26.

Drumo R, Pesciaroli M, Ruggeri J, Tarantino M, Chirullo B, Pistoia C, et al. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium exploits inflammation to modify swine intestinal microbiota. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2015;5:106.

Behnsen J, Jellbauer S, Wong CP, Edwards RA, George MD, Ouyang W, et al. The cytokine IL-22 promotes pathogen colonization by suppressing related commensal bacteria. Immunity. 2014;40(2):262–73.

Grizotte-Lake M, Zhong G, Duncan K, Kirkwood J, Iyer N, Smolenski I, et al. Commensals suppress intestinal epithelial cell retinoic acid synthesis to regulate interleukin-22 activity and prevent microbial dysbiosis. Immunity. 2018;49(6):1103–15.

Lo BC, Shin SB, Canals Hernaez D, Refaeli I, Yu HB, Goebeler V, et al. IL-22 preserves gut epithelial integrity and promotes disease remission during chronic Salmonella infection. J Immunol. 2019;202(3):956–65.

Yang GY, Yu J, Su JH, Jiao LG, Liu X, Zhu YH. Oral administration of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG ameliorates Salmonella Infantis-induced inflammation in a pig model via activation of the IL-22BP/IL-22/STAT3 pathway. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:323.

Li MO, Flavell RA. Contextual regulation of inflammation: a duet by transforming growth factor-beta and interleukin-10. Immunity. 2008;28(4):468–76.

Dudakov JA, Hanash AM, van den Brink MR. Interleukin-22: immunobiology and pathology. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:747–85.

Kim TH, Lee EK, Lee MJ, Kim JH, Yang WS. Fucoidan inhibits activation and receptor binding of transforming growth factor-beta1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;432(1):163–8.

Wang L, Zhang P, Li X, Zhang Y, Zhan Q, Wang C. Low-molecular-weight fucoidan attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis: possible role in inhibiting TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition through ERK pathway. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11(4):2590–602.

Grassl GA, Valdez Y, Bergstrom KS, Vallance BA, Finlay BB. Chronic enteric salmonella infection in mice leads to severe and persistent intestinal fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(3):768–80.

Sashinami H, Yamamoto T, Nakane A. The cytokine balance in the maintenance of a persistent infection with Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium in mice. Cytokine. 2006;33(4):212–8.

Janczyk P, Kreuzer S, Assmus J, Nockler K, Brockmann GA. No protective effects of high-dosage dietary zinc oxide on weaned pigs infected with Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium DT104. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79(9):2914–21.

Pei X, **ao Z, Liu L, Wang G, Tao W, Wang M, et al. Effects of dietary zinc oxide nanoparticles supplementation on growth performance, zinc status, intestinal morphology, microflora population, and immune response in weaned pigs. J Sci Food Agric. 2019;99(3):1366–74.

Wang X, Ou D, Yin J, Wu G, Wang J. Proteomic analysis reveals altered expression of proteins related to glutathione metabolism and apoptosis in the small intestine of zinc oxide-supplemented piglets. Amino Acids. 2009;37(1):209–18.

Mukhopadhya A, O'Doherty JV, Sweeney T. A combination of yeast beta-glucan and milk hydrolysate is a suitable alternative to zinc oxide in the race to alleviate post-weaning diarrhoea in piglets. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):616.

Janczyk P, Busing K, Dobenecker B, Nockler K, Zeyner A. Effect of high dietary zinc oxide on the caecal and faecal short-chain fatty acids and tissue zinc and copper concentration in pigs is reversible after withdrawal of the high zinc oxide from the diet. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2015;99(Suppl S1):13–22.

Johanns VC, Ghazisaeedi F, Ep** L, Semmler T, Lubke-Becker A, Pfeifer Y, et al. Effects of a four-week high-dosage zinc oxide supplemented diet on commensal Escherichia coli of weaned pigs. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2734.

Walsh AM, Sweeney T, O'Shea CJ, Doyle DN, O'Doherty JV. Effect of dietary laminarin and fucoidan on selected microbiota, intestinal morphology and immune status of the newly weaned pig. Br J Nutr. 2013;110(9):1630–8.

Rattigan R, Sweeney T, Maher S, Thornton K, Rajauria G, O'Doherty JV. Laminarin-rich extract improves growth performance, small intestinal morphology, gene expression of nutrient transporters and the large intestinal microbial composition of piglets during the critical post-weaning period. Br J Nutr. 2020;123(3):255–63.

Vigors S, O'Doherty JV, Rattigan R, McDonnell MJ, Rajauria G, Sweeney T. Effect of a laminarin rich macroalgal extract on the caecal and colonic microbiota in the post-weaned pig. Mar Drugs. 2020;18(3):157.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Assoc. Prof. Finola Leonard from the School of Veterinary Medicine, University College Dublin for her help and advice in the design of the study and laboratory analysis of the samples and thank the laboratory staff in the Backweston Central Veterinary Research laboratory for their assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) [grant number: 14/IA/2548]. SFI had no involvement in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The contribution of the authors were as follows; conceptualization of experiment and funding acquisition, TS and JVO’D; design of experiment, TS, JVO’D and BV; production and analysis of seaweed extracts, SM, RR, GR and MG-V; animal work, BV, SM and VG; laboratory analysis, BV, CK and MR; data curation, analysis and interpretation, BV, TS and JVO’D; writing of original draft BV; review and editing, BV, TS, JVO’D, MR, SM, VG, CK, RR, GR and MG-V. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experimental procedures described in this study were approved by the University College Dublin Animal Research Ethics Committee (AREC-18-33-Sweeney) and Health Products Regulatory Authority (AE18982/P170) and conducted in accordance with the Irish legislation (SI no. 534/2012) and the EU directive 2010/63/EU for animal experimentation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

List of 16S rRNA regions incorporated into plasmids for the preparation of specific Escherichia coli clones used for the quantification of Salmonella enterica, Lactobacillus spp., total bacteria, Enterobacteriaceae, Bifidobacterium spp., Prevotella spp. and butyrate-producing bacteria.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Venardou, B., O’Doherty, J.V., Maher, S. et al. Potential of a fucoidan-rich Ascophyllum nodosum extract to reduce Salmonella shedding and improve gastrointestinal health in weaned pigs naturally infected with Salmonella. J Animal Sci Biotechnol 13, 39 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-022-00685-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-022-00685-4