Abstract

Introduction

Laparoscopic surgery has greatly improved surgical outcome in many areas of abdominal surgery. But many concerns of safety have limited its application in abdominal trauma. We hypothesized that laparoscopy could be safe and efficacious in treatment of patients with abdominal trauma, and reduce the laparotomy related complications (i.e. wound infection, pain, or long hospital stay) as avoiding unnecessary laparotomy.

Methods

From January 2006 to August 2012, a total of 111 patients underwent emergent surgical exploration (laparoscopic, 41; open laparotomy, 70) in Andong General Hospital. Of the 41 patients subjected to laparoscopy, 30 patients had suffered blunt trauma, the remaining 11 patients had sustained penetrating trauma. 31 patients were treated exclusively by laparoscopy and 10 patients underwent laparoscopy-assisted surgery.

Results

The conversion rate was 18%. Major complication was none without postoperative mortality. Comparing laparoscopic surgery with open laparotomy, lesser wound infection, early gas passage, and shorter hospital stay. Otherwise operative times were similar, and neither approach was complicated by missed injury or postoperative intra-abdominal abscess.

Conclusions

Laparoscopic surgery can be performed safely whether injuries are blunt or penetrating, given hemodynamic stability and proper technique. Patients may thus benefit from the shorter hospital stays, greater postoperative comfort (less pain), quicker recoveries, and low morbidity/mortality rates that laparoscopy affords.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Laparoscopy has greatly improved surgical outcomes in many areas of elective abdominal surgery. In acute care surgery, laparoscopy is becoming widely accepted and used with significant advantages in the majority of ACS patients in certain centers with specific experience and laparoscopic skills [1]. However, a number of safety issues have limited its application in abdominal trauma [2]. Due to a high rate of missed injuries, laparoscopy was not well-received for diagnostic evaluation of trauma to the abdomen. However, equipment improvements over time and growing experience on the part of surgeons have overcome former misgivings with respect to penetrating abdominal injuries. Laparoscopy has being slowly attempted as a diagnostic tool for such patients, provided they are hemodynamically stable [3,4]. Under these circumstances, laparoscopic surveillance has been shown to reduce the negative laparotomy rate [5-8]. On the other hand, its utility in patients sustaining blunt abdominal trauma has received only minor attention [9], and the therapeutic role of laparoscopy in trauma patients is still evolving. It was our contention that laparoscopy could be safe and efficacious in both diagnosis and treatment of patients with abdominal trauma, eliminating unnecessary laparotomies and the risks attached.

Methods

Medical records from the trauma registry at Andong General Hospital were reviewed retrospectively between January, 2006 and August, 2012. A total of 111 patients required surgical exploration for abdominal trauma in this time frame. For patients with penetrating injuries, breach of the peritoneum was grounds for surgical exploration. In patients with blunt injuries, those with unexplained free fluid/air by computed tomography (CT) or worrisome clinical signs and symptoms (ie, evidence of peritoneal irritation, tachycardia, and leukocytosis) were typically evaluated surgically. Five surgeons, each well-trained in colorectal, upper gastrointestinal, or hepatobiliary laparoscopy, performed the collective procedures. Laparoscopy was used at the discretion of the attending trauma surgeon, regardless of the nature of trauma (blunt or penetrating), but hemodynamic stability was mandatory. Therefore, to match two groups, 15 patients that had preoperative hemodynamic instability were excluded in the open group.

Demographic and clinical data retrieved included the type of injury, hemodynamic status on admission, indication for surgery, operative findings, therapeutic procedures performed, need for conversion (to laparotomy), Injury Severity Score (ISS), Sum of abdominal Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS), presence of peritonitis, operative time, postoperative complications, and mortality. Complications of note were wound infection (requiring delayed closure), anastomotic leak, bleeding with reoperation, missed injury, and postoperative intra-abdominal abscess development. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Laparoscopic techniques

Initially, a 10-mm trocar was inserted via infraumbilical incision. A pneumoperitoneum was then created, using carbon dioxide to induce and maintain (at 12 mmHg) pressure. A 0-degree angle, 10-mm laparoscope was generally used for abdominal exploration. Two additional 5-mm laparoscopic ports were also placed under direct vision at right iliac fossa and at right upper quadrant (paramedial area), with mirror-image ports on the left as needed (Figure 1). Upon insertion of the laparoscope, a search for blood, bile, or intestinal contents was done. Standard examination included inspection of the spleen and liver for bleeding, a check for hollow viscus injury from stomach to rectum, and assessment of small bowel from Treitz’s ligament to ileocecal valve. Using atraumatic bowel graspers, small bowel and mesentery were elevated and appraised in segments. By crossing the graspers, the reverse sides were similarly viewable [10] (Figure 2). This approach was repeated until reaching ileocecal valve, at which point colon was inspected from cecum to rectum. Ultimately, the lesser sac was pierced (through gastrocolic ligament), allowing visualization of posterior gastric wall and most of pancreas (body and tail).

Any bowel perforations detected were simply sutured (3–0 vicryl or silk) or closed by linear stapling (endo-GIA®) in the course of the procedure (Figure 3). If segmental resection was needed, a mini-laparotomy was performed by extending the umbilical port to permit laparoscopy-assisted extracorporeal surgery. Bleeding from torn mesentery was controlled by suture ligation or cauterization (Ligasure® or Harmonic scalpel®) (Figure 4). For large volumes of spilled soilage or hematoma (mostly clots) not amenable to aspiration by conventional mode of endo-suction, evacuation was achieved by direct insertion of a silastic tube through a 12-mm port (Figure 5).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis relied on standard windows software (SPSS v20, Chicago, IL), expressing group variables as mean ± standard deviation. Student’s t-test was applied to independent samples of continuous variables, whereas chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical values. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

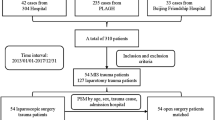

In a 7-year period, 111 patients underwent surgery for abdominal trauma. Of these, 41 patients (36.9%) retained the hemodynamic stability required for a laparoscopic procedure and subsequent analysis. Laparoscopy alone was sufficient in 31 (75.6%) instances, whereas 10 patients underwent laparoscopy-assisted procedures. The other 70 patients (63.1%) were treated by open laparotomy, including any conversions (Figure 6). 15 patients of open laparotomy were excluded due to hemodynamic instability for the comparison between laparoscopy and open laparotomy. Therefore, we analyzed laparoscopic group (n = 41) and open group (n = 55).

Causes of abdominal trauma

Of the 41 patients subjected to laparoscopy, 30 patients (73.2%) had suffered blunt trauma, largely as a consequence of traffic accidents. The remaining 11 patients had sustained penetrating trauma, primarily stab injuries (Table 1).

Injured organs

With blunt trauma, small bowel perforation was most common, followed by torn mesentery. Three patients suffering penetrating trauma also had colon or small bowel perforations. Hemoperitoneum often resulted from injuries of omentum, mesentery, abdominal wall, or spleen (Table 2).

Methods of operation

In the 31 patients treated exclusively through laparoscopy, simple closures with suture or stapling (endo-GIA®) sufficed for 13 patients, whereas 11 patients required hemostasis using Ligasure®, Harmonic scalpel®, or suture. If segmental resection was needed for multiple perforations or transection of bowel or for intestinal ischemic changes due to mesenteric tearing, a laparoscopy-assisted mini-laparotomy was performed (Table 3).

Conversion to open laparotomy

The rate of conversion to open laparotomy was 18% (9/50). In early attempts, three laparoscopic procedures were done for diagnosis only. Reasons for conversion were uncontrolled bleeding, voluminous hematoma or spilled bowel contents, massive adhesions from prior surgery, and poor visibility due to edematous bowel (Table 4).

Comparisons between laparoscopic and open surgery

Comparing laparoscopic surgery with open laparotomy (excluding 15 patients with hemodynamic instability), The parameters presenting severity (ISS, Sum of abdominal AIS, and the presence of peritonitis) were not different between two groups. Wound infection necessitating delayed closure occurred with significantly greater frequency after open laparotomy, and other temporal parameters (time to passage of gas and hospital stay) of open laparotomy were prolonged. Otherwise, respective operative times were similar, and neither approach was complicated by missed injury or postoperative intra-abdominal abscess (Table 5).

Discussion

It is generally upheld that patients who undergo laparoscopy, rather than conventional open surgery, are privy to quicker recovery, less pain, and faster resumption of normal daily routines [11,12]. Laparoscopy is thus a universal choice for elective abdominal surgery. However, a number of concerns have limited its application in abdominal trauma.

Until recently, the presence of peritonitis was a perceived contraindication for laparoscopy, based on the theoretical risk of malignant hypercapnia and toxic shock syndrome. The presumptive risk of malignant hypercapnia implies greater carbon dioxide absorption in the presence of severe intra-abdominal infection and inflammation of the peritoneum; and the danger of toxic shock syndrome is based on potential passage of bacteria and toxins into circulation, due to increased intraperitoneal pressure [13,14]. However, numerous reports of successful outcomes in duodenal and colonic perforation [15-17] soon followed the ground-breaking laparoscopic treatment of a perforated peptic ulcer with peritonitis [18,19]. Unfortunately, treatment of traumatic peritonitis and hemoperitoneum is where laparoscopic surgery has lagged. We have found the above concerns unwarranted with either approach.

Two publications in the 1920s were the first to suggest use of laparoscopy in diagnosing traumatic hemoperitoneum or for detecting blood from traumatic rupture of a viscus [20]. However, the modern concept of diagnostic laparoscopy for trauma was proffered in the 1960s by Heselson [21-23], who reported a series of 68 victims of trauma. In this cohort, laparoscopy was performed to detect hemoperitoneum, penetration of parietal peritoneum, and injury to abdominal organs. Thus the safety, efficacy, and economic benefits of laparoscopy, such as reduced hospitalization time and avoidance of unnecessary laparotomies, were demonstrated. Although infrequently reported, laparoscopy has also served as a therapeutic tool in selected trauma scenarios [24,25], to include the following: autotransfusion of hemoperitoneum [26]; stapling or suturing of small-intestinal wounds; stapling or suturing of stomach and diaphragmatic injuries [24]; splenorrhaphy, hepatorrhaphy, cautery, and topical hemostasis of spleen and liver injuries [24,25,27,28]; laparoscopy-assisted sigmoid colostomy [29]; and application of Ligaclips® to control mesenteric bleeding [30].

When first used for trauma, laparoscopy resulted in high rates of missed injury (41-77%), generating considerable criticism [31]. One of the most serious concerns was its lack of consistency in detecting small bowel damage [4,31,32], which is the main reason surgeons still hesitate today; but because these studies involved both prospective and retrospective analyses and procedures were not standardized, the data are difficult to interpret. In addition, the learning curve of laparoscopic surgery was ignored in early evaluations, and subjective preferences do seem to drive decisions during laparoscopy. One prior report underscored the reliability of laparoscopy as a tool for evaluating traumatic injuries, when used for specific indications and with appropriate technique [24,33,34]. Choi [10] and Kawahara, et al. [8] devised systematic laparoscopic explorations of the abdomen that resulted in no missed injuries. In accordance with the method of Choi, we found it relatively easy to effectively inspect all abdominal organs, without missing an injury.

The primary limitation of laparoscopic intervention is the poor visibility conferred by excessively edematous bowel or uncontrolled active bleeding at presentation. These are the major motivations for conversion to open laparotomy. Edema of the bowel is a time-dependent process. Thus, patients presenting shortly after the traumatic event are more easily managed through laparoscopy, whereas lengthier time intervals usually portend severe intestinal edema. Not only is the laparoscopic window obscured by edematous bowel, but traction injury is more likely to occur during manipulation. One patient in our study was converted to open laparotomy on the basis of intestinal edema. On admission, sedation should be administered for the mechanical ventilation required by respiratory failure due to massive lung contusion, so the initial evaluation of abdomen was omitted, unfortunately. finally, bowel perforation was overlooked initially and was detected three days later after reducing a sedative.

Another cause of open conversion is the spillage of large-sized particulates that cannot be aspirated via the usual mode of endo-suction. However, we were able to achieve complete evacuation in this event by direct insertion of a silastic tube through a 12-mm port. Subsequently, our fears of postoperative intra-abdominal abscess never materialized. A fair number of our open conversions stemmed from trial-and-error in early experience, contributing to an open conversion rate of 18% (9/50). In three patients, the laparoscopies were done for diagnostic purposes only. Two patients with uncontrolled splenic bleeding were converted, as well as two others where large volumes of hematoma and spilled soilage were encountered. With more experience, these conversions very well could have been avoided.

Traumatic abdominal injury is traditionally subject to open exploration and remains a challenge for the general surgeon, especially with respect to controlling wound-related complications. Wound complications still play a major role in lengthy hospital stays and may lead to other delayed morbidities. Our aim was to extend the benefits of minimally invasive surgery to traumatic abdominal injury, thereby decreasing postoperative complications. Indeed, wound infections requiring delayed closure were limited to five patients following open laparotomy. By comparison, none of the patients undergoing laparoscopy suffered a wound complication.

Various temporal parameters (ie, time to passage of gas and hospital stay) were also comparatively better with laparoscopy, although some qualification is needed. Hospital stay was difficult to determine as a function of abdominal surgery in a setting of combined injuries (musculoskeletal, cerebrovascular, pulmonary, etc.). Therefore, we defined hospital stay by points at which oral intake was possible and wound healing was complete.

In conclusion, although we disclose that this study was many limitations caused by selection bias and retrospective study, laparoscopy gradually has being accepted as a diagnostic and/or treatment modality for penetrating abdominal injuries in patients that are hemodynamically stable. The relative rates of morbidity/mortality, postoperative complications, and missed injury are low and compare favorably with an open approach. However, laparoscopic surgery can be performed safely whether injuries are blunt or penetrating, given hemodynamic stability and proper technique. Patients may thus benefit from the shorter hospital stays, greater postoperative comfort (less pain), quicker recoveries, and low morbidity/mortality rates that laparoscopy affords.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ISS:

-

Injury severity score

- AIS:

-

Abbreviated injury scale

References

Di Saverio S. Emergency laparoscopy: a new emerging discipline for treating abdominal emergencies attempting to minimize costs and invasiveness and maximize outcomes and patients' comfort. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77:338–50.

Rossi P, Mullins D, Thal E. Role of laparoscopy in the evaluation of abdominal trauma. Am J Surg. 1993;166:707–10. discussion 710–701.

Fabian TC, Croce MA, Stewart RM, Pritchard FE, Minard G, Kudsk KA. A prospective analysis of diagnostic laparoscopy in trauma. Ann Surg. 1993;217:557–64. discussion 564–555.

Ivatury RR, Simon RJ, Stahl WM. A critical evaluation of laparoscopy in penetrating abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1993;34:822–7. discussion 827–828.

Simon RJ, Rabin J, Kuhls D. Impact of increased use of laparoscopy on negative laparotomy rates after penetrating trauma. J Trauma. 2002;53:297–302. discussion 302.

Chol YB, Lim KS. Therapeutic laparoscopy for abdominal trauma. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:421–7.

Murray JA, Demetriades D, Asensio JA, Cornwell 3rd EE, Velmahos GC, Belzberg H, et al. Occult injuries to the diaphragm: prospective evaluation of laparoscopy in penetrating injuries to the left lower chest. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:626–30.

Kawahara NT, Alster C, Fujimura I, Poggetti RS, Birolini D. Standard examination system for laparoscopy in penetrating abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 2009;67:589–95.

Kaban GK, Novitsky YW, Perugini RA, Haveran L, Czerniach D, Kelly JJ, et al. Use of laparoscopy in evaluation and treatment of penetrating and blunt abdominal injuries. Surg Innov. 2008;15:26–31.

Choi GS. Systematized laparoscopic surgery in abdominal trauma. J Korean Surg Soc. 1998;54:492–500.

Druart ML, Van Hee R, Etienne J, Cadiere GB, Gigot JF, Legrand M, et al. Laparoscopic repair of perforated duodenal ulcer. A prospective multicenter clinical trial. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:1017–20.

Lau WY, Leung KL, Kwong KH, Davey IC, Robertson C, Dawson JJ, et al. A randomized study comparing laparoscopic versus open repair of perforated peptic ulcer using suture or sutureless technique. Ann Surg. 1996;224:131–8.

Diebel LN, Wilson RF, Dulchavsky SA, Saxe J. Effect of increased intra-abdominal pressure on hepatic arterial, portal venous, and hepatic microcirculatory blood flow. J Trauma. 1992;33:279–82. discussion 282–273.

Maddaus MA, Ahrenholz D, Simmons RL. The biology of peritonitis and implications for treatment. Surg Clin North Am. 1988;68:431–43.

Katkhouda N, Mouiel J. A new technique of surgical treatment of chronic duodenal ulcer without laparotomy by videocoelioscopy. Am J Surg. 1991;161:361–4.

Regan MC, Boyle B, Stephens RB. Laparoscopic repair of colonic perforation occurring during colonoscopy. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1073.

O'Sullivan GC, Murphy D, O'Brien MG, Ireland A. Laparoscopic management of generalized peritonitis due to perforated colonic diverticula. Am J Surg. 1996;171:432–4.

Nathanson LK, Easter DW, Cuschieri A. Laparoscopic repair/peritoneal toilet of perforated duodenal ulcer. Surg Endosc. 1990;4:232–3.

Mouret P, Francois Y, Vignal J, Barth X, Lombard-Platet R. Laparoscopic treatment of perforated peptic ulcer. Br J Surg. 1990;77:1006.

Short AR. The uses of coelioscopy. Br Med J. 1925;2:254–5.

Heselson J. The value of peritoneoscopy as a diagnostic Aid in abdominal conditions. Cent Afr J Med. 1963;31:395–8.

Heselson J. Peritoneoscopy; a review of 150 cases. S Afr Med J. 1965;39:371–4.

Heselson J. Peritoneoscopy in abdominal trauma. S Afr J Surg. 1970;8:53–61.

Zantut LF, Ivatury RR, Smith RS, Kawahara NT, Porter JM, Fry WR, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic laparoscopy for penetrating abdominal trauma: a multicenter experience. J Trauma. 1997;42:825–9. discussion 829–831.

Chen RJ, Fang JF, Lin BC, Hsu YB, Kao JL, Kao YC, et al. Selective application of laparoscopy and fibrin glue in the failure of nonoperative management of blunt hepatic trauma. J Trauma. 1998;44:691–5.

Smith RS, Meister RK, Tsoi EK, Bohman HR. Laparoscopically guided blood salvage and autotransfusion in splenic trauma: a case report. J Trauma. 1993;34:313–4.

Hallfeldt KK, Trupka AW, Erhard J, Waldner H, Schweiberer L. Emergency laparoscopy for abdominal stab wounds. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:907–10.

Smith RS, Fry WR, Morabito DJ, Koehler RH, Organ Jr CH. Therapeutic laparoscopy in trauma. Am J Surg. 1995;170:632–6. discussion 636–637.

Namias N, Kopelman T, Sosa JL. Laparoscopic colostomy for a gunshot wound to the rectum. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1995;5:251–3.

VanderKolk WE, Garcia VF. The use of laparoscopy in the management of seat belt trauma in children. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1996;6:S45–9.

Villavicencio RT, Aucar JA. Analysis of laparoscopy in trauma. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189:11–20.

Becker HP, Willms A, Schwab R. Laparoscopy for abdominal trauma. Chirurg. 2006;77:1007–13.

Kawahara N, Zantut LF, Poggetti RS, Fontes B, Bernini C, Birolini D. Laparoscopic treatment of gastric and diaphragmatic injury produced by thoracoabdominal stab wound. J Trauma. 1998;45:613–4.

Krausz MM, Abbou B, Hershko DD, Mahajna A, Duek DS, Bishara B, et al. Laparoscopic diagnostic peritoneal lavage (L-DPL): A method for evaluation of penetrating abdominal stab wounds. World J Emerg Surg. 2006;1:3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KHL as lead investigator made substantial contributions to conception, design, collection of data and management of patients; BSC, JYK, and SSK managed patients. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, K.H., Chung, B.S., Kim, J.Y. et al. Laparoscopic surgery in abdominal trauma: a single center review of a 7-year experience. World J Emerg Surg 10, 16 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-015-0007-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-015-0007-8