Abstract

Background

Adults infected with Plasmodium spp. in endemic areas need to be re-evaluated in light of global malaria elimination goals. They potentially undermine malaria interventions but remain an overlooked aspect of public health strategies.

Methods

This study aimed to estimate the prevalence of Plasmodium spp. infections, to identify underlying parasite species, and to assess predicting factors among adults residing in an endemic area from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). A community-based cross-sectional survey in subjects aged 18 years and above was therefore carried out. Study participants were interviewed using a standard questionnaire and tested for Plasmodium spp. using a rapid diagnostic test and a nested polymerase chain reaction assay. Logistic regression models were fitted to assess the effect of potential predictive factors for infections with different Plasmodium spp.

Results

Overall, 420 adults with an estimated prevalence of Plasmodium spp. infections of 60.2% [95% CI 55.5; 64.8] were included. Non-falciparum species infected 26.2% [95% CI 22.2; 30.5] of the study population. Among infected participants, three parasite species were identified, including Plasmodium falciparum (88.5%), Plasmodium malariae (39.9%), and Plasmodium ovale (7.5%) but no Plasmodium vivax. Mixed species accounted for 42.3% of infections while single-species infections predominated with P. falciparum (56.5%) among infected participants. All infected participants were asymptomatic at the time of the survey. Adults belonging to the “most economically disadvantaged” households had increased risks of infections with any Plasmodium spp. (adjusted odds ratio, aOR = 2.87 [95% CI 1.66, 20.07]; p < 0.001), compared to those from the "less economically disadvantaged” households. Conversely, each 1 year increase in age reduced the risk of infections with any Plasmodium spp. (aOR = 0.99 [95% CI 0.97, 0.99]; p = 0.048). Specifically for non-falciparum spp., males had increased risks of infection than females (aOR = 1.83 [95% CI 1.13, 2.96]; p = 0.014).

Conclusion

Adults infected with malaria constitute a potentially important latent reservoir for the transmission of the disease in the study setting. They should specifically be taken into account in public health measures and translational research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria is a life-threatening illness caused by Plasmodium spp. parasites transmitted to humans through the bites of infected mosquitoes. Despite being preventable and treatable, the disease remains a major public health problem globally, with its highest burden occurring in Africa (i.e., ~ 95% of cases and associated deaths) [1]. More than 200 million cases are reported yearly across African countries due to four main Plasmodium species, including Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium ovale, and Plasmodium vivax [1]. Among them, P. falciparum infections are of greatest concern as they are the most prevalent and fatal due to serious complications occurring mainly in children under 5 years old and pregnant women [1]. Beyond its high morbidity and mortality across the continent, malaria diverts substantial financial resources from individuals and countries towards prevention and treatment efforts [2, 3]. Thus, while affecting the health and wealth of nations, it is both a consequence and a cause of poverty and inequalities [3, 4]. To address this situation, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the “Global Technical Strategy (GTS) for Malaria 2016–2030” as a global agenda to eliminate malaria by 2030, with clear targets and specific milestones [5]. Toward this ambitious plan, the WHO urges countries to implement interventions tailored to local conditions, with a strong emphasis on vector control, early diagnosis, and rapid treatment [1, 5]. However, several African countries have not yet succeeded in achieving GTS milestones despite efforts [6,7,8]. In these countries, adults exposed to Plasmodium spp. are often overshadowed by better-targeted children under five and pregnant women, even though they represent a major challenge for malaria control and elimination efforts. To optimally meet WHO’s ambitions, existing strategies must be optimized, and new strategies developed to account for all population categories including adults infected with Plasmodium spp.

Adults infected with Plasmodium spp. represent a particularly complex problem for the epidemiology and pathogenicity of malaria in high endemicity settings such as Sub-Saharan Africa [9]. Indeed, cumulative exposure to Plasmodium spp. leads to the acquisition of anti-parasitic and anti-disease immunity that reduces blood parasite levels, prevents symptoms, and provides substantial protection against severe malaria and associated deaths [10, 11]. Adults logically accumulate more infections over time and almost all develop this immunity, unless they have specific underlying health problems such as pregnancy or HIV/AIDS [10]. However, the acquired immunity remains partial and does not fully prevent infections. Semi-immune adults can still be infected with Plasmodium spp. while develo** mild or no symptoms and carrying parasites in their blood for prolonged periods [11,12,13]. In sub-Saharan Africa, community surveys report Plasmodium spp. prevalence estimates above 70% but also below 5% among asymptomatic individuals [14,15,16,17,18,19]. Regional variations are likely linked to several local factors, including broad ecological variations (e.g., altitude, temperature, seasons), different existing vector species, and varying intervention coverage. Although often asymptomatic, chronic infections with Plasmodium spp. may have a long-term impact on the health of individuals with complications such as recurrent symptomatic episodes, anemia, and cognitive impairment [12, 15]. Ultimately, they would substantially contribute to lower productivity, higher healthcare costs, and increased economic strain among African populations already facing other societal issues. Moreover, infected adults often carry low blood levels of parasites in endemic areas thereby posing significant challenges to standard diagnostic approaches, including rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) and conventional microscopy [8, 12, 13]. As the expertise and diagnostic tools needed to properly address these challenges are still very limited on the continent, eliminating malaria is proving particularly difficult. Since asymptomatic adults do not necessarily seek care, they would persist in the community while retaining their ability to transmit Plasmodium to others through mosquito bites. They thereby constitute an important part of the living reservoir of parasites which maintains infections within communities [11,12,13, 20,21,22,23]. Plasmodium spp. infections in adults therefore affect both individuals and the wider community, requiring further recognition through policy decision-making and tailored interventions in the light of targeted GTS milestones.

Located within the WHO African region, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is one of the countries where adults infected with Plasmodium spp. represent the most a gap in public health. This vast country has continuously hosted more than 10% of the global malaria burden, especially since 2015 [1, 6, 24, 25]. Nearly 97% of the Congolese population resides in areas where malaria transmission is stable 8–12 months per year, involving P. falciparum, P. malariae, P. vivax, and P. ovale [19, 26,27,28,29]. A significant proportion of community infections with these Plasmodium spp. is, therefore, expected among semi-immunized adults [25]. Moreover, beyond the country's tropical climate and inadequate sanitation, socio-economic factors such as poverty and lack of education likely make more adults vulnerable to malaria [4]. However, public health efforts aimed at mitigating the impact of malaria have preferentially focused on population categories other than adults, notably young children and pregnant women [13, 25]. Likewise, malaria diagnosis and treatment policies remain primarily focused on P. falciparum [25, 30] despite that three other Plasmodium spp. (i.e., P. malaria, P. ovale, and P. vivax) are endemic across the country and would be more prevalent among adults. Furthermore, in the absence of targeted interventions, adults infected with Plasmodium spp. remain underreported in national surveys such as the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS), the Health Management Information System (HMIS), or the District Health Information Software 2 (DHIS). The prevalence and impact of Plasmodium spp. infections are thus widely underestimated in adults. Although P. falciparum remains the major species, non-falciparum species may increasingly contribute to infections [11, 22]. They could therefore raise additional obstacles to malaria elimination efforts due to limited access to accurate diagnosis, to possible divergent responses to anti-malarial drugs, and to the presence of dormant liver-stage parasites associated with relapses [11]. In this context, the country’s aim to reduce its malaria-related morbidity and mortality by 90% by 2030 [25], could be difficult to achieve without an adequate response to adults infected with Plasmodium spp. Further research on Plasmodium spp. is warranted to draw deserved attention to infections among adults and provide evidence for tailored interventions to achieve sustainable malaria control throughout the country. The presents study was therefore conducted in an endemic area of the DRC to estimate the prevalence of Plasmodium spp. infections among adults while determining the underlying parasite species, associated clinical aspects and predictive factors. This work is timely and relevant to national malaria programmes in the DRC and the most endemic regions of SSA, where the GTS elimination milestones appear most difficult to achieve and sustain.

Methods

Study area

This study was carried out in the Lukelenge health zone which is located at approximately 533 m altitude and extends between − 6.3 and − 6.1 latitude and 23.61 to 25.63 longitude, at the western outskirts of Mbujimayi (Fig. 1). Mbujimayi is the capital city of Kasai Oriental—a region of 9425 km2 corresponding to the smallest province of the DRC. The land use pattern in this region is heterogeneous, with densely populated areas separated by large semi-rural and rural areas where agriculture is practiced. Administratively, Kasai Oriental comprises one city (i.e., Mbujimayi) surrounded by five rural territories (i.e., Tshilenge, Katanda, Kabeya Kamuanga, Miabi, and Lupatapata). Two thirds of the region’s population (3,189,886 inhabitants) reside in Mbujimayi with a density of 326 inhabitants per km2 [31]. The local health system is organized as a health district, divided into 18 health zones. Health zones are the primary operational units that autonomously plan and implement national health policies, each covering an area of 100,000 to 150,000 and 200,000 to 250,000 inhabitants in rural and urban areas respectively [26, 32]. On a national scale, the DRC’s health system has a pyramidal architecture with the health zone as its base. Divided on average into 15 health areas which cover 10,000 to 15,000 inhabitants, a health zone includes a general referral hospital connected to a network of health centers and community health workers interacting with the population [32]. Mbujimayi city spans nine health zones, including Lukelenge which has a semi-rural profile. Predictions from the Malaria Atlas Project (MAP) (https://malariaatlas.org/pf-pv-cubes-2019/) [5, 7] locate Lukelenge in an area of significant endemic malaria within the country (Additional file 1: Fig S1). The climate is tropical and humid (AW4 according to the Koppen classification), with a long rainy season lasting from September to April and a short dry season, from May to August [33]. The present field survey took place in August 2018, at the end of the dry season.

Study population and design

A cross-sectional community-based survey at the level of households in the study area was carried out. Households were selected using a simple random sampling process based on a frame established from satellite images and geospatial datasets that were captured over the study area with Google Earth (www.google.com/intl/eng/earth). In each household, a single adult (i.e. an individual aged ≥ 18 years) was recruited according to the “first come, first included” principle. Among potentially eligible participants, those for whom a good quality blood sample or complete interview could not be obtained were excluded. The minimum sample size was determined by assuming that this was a single population survey with a 33.8% prevalence of Plasmodium spp. infections, based on existing estimates [28] and a marginal error of 5%, a confidence interval of 95% (z-score = 1.96), and an expected coverage rate of 90%. Therefore, while the survey targeted a minimum of 378 subjects, 420 were ultimately included, resulting a statistical power above 90%.

Data collection and definition of variables

A standard semi-open questionnaire was used to collect information about participants and their households through an individual interview and brief clinical examination (Additional file 2). In addition to sociodemographic data, individual information collected included use of any malaria preventive measures, possible uptake of anti-malarial drugs, and history of putative symptomatic malaria episodes in the last 3 days, 1 month, and 6 months. Additionally, during the survey, axillary temperature and test results for Plasmodium spp. on each participant were recorded. Subsequently, a symptomatic malaria episode was defined based on detected fever (i.e., axillary temperature above 37.7 °C) or on a self-reported history of acute symptoms, including fever, chills, generalized body aches, or headache. Conversely, during the survey, an asymptomatic Plasmodium spp. infection was defined based on as a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) result for Plasmodium spp. without any prior antimalarial drugs uptake and any malaria acute symptoms occurring over the last 3 days. Furthermore, different study variables were combined to define different categories of participants. Participants were considered to have a “high” or “low” education level whenever they had or had not reached secondary school. Besides individual information, the questionnaire also covered the characteristics of the households to which each study participant belonged. Housing conditions (i.e. the structure of walls, floors, and roofs of houses) were used to define a two-level socio-economic categorization of households based on principal components analysis (PCA). As a result, households were classified as being among either “most economically disadvantaged” or “least economically disadvantaged”. Finally, the number of household members sharing a slee** room was used to define an occupancy index reflecting the crowding of houses. “Overcrowded households” were households whose occupancy index was higher than that of the median population index.

Blood samples processing and malaria testing

A skin puncture on a participant's finger was performed to collect capillary blood samples for malaria testing. A fresh drop of blood was thus gently transferred to a SD Bioline Malaria Ag Pf test (Standard Diagnostics, Suwon city, Republic of Korea) for detecting the histidine-rich protein 2 (HRP2) of P. falciparum according to the Manufacturer’s instructions. Then, 70 µl of blood were sampled with a single-use 75 mm micro-hematocrit capillary tube (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Each blood sample was spotted and dried at ambient temperature on a Whatman 903 filter card (GE Healthcare Ltd., UK) for storage in a zipped plastic bag including a desiccant within it. Dried blood spots (DBS) were afterward shipped to the Department of Parasitology, Osaka Metropolitan University Graduate School of Medicine for molecular testing of Plasmodium spp. infections following a previously developed approach [34]. Briefly, a quarter of each DBS (approximately 17.5 µl) was sterilely cut and allocated for DNA extraction using the QIAamp Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Then, the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase III (cox3) gene of Plasmodium spp. was amplified using a nested PCR protocol that detects and differentiates the four major Plasmodium species (i.e., P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, and P. malariae) [34,48]. Non-falciparum infections therefore increased attention given the potential complexities they may pose for malaria control, management, and research. First, the biology of non-falciparum species remains less understood, negatively impacting the successful development of species-specific control strategies [55]. Typically, non-falciparum infections may be chronic or dormant for long periods due to hypnozoite formation [55], further complicating the practical understanding of their epidemiology. Second, during co-infections, P. malariae can increase P. falciparum gametocyte production, suggesting that complex epidemiological interactions exist between species [56, 57]. Third, in addition to their propensity for hypnozoite formation and their differential drug susceptibility, non-falciparum species pose significant obstacles to early and accurate diagnosis that potentially undermine any rational management especially in resource-limited settings such as the DRC [55, 58]. Finally, although considered benign, non-falciparum infections can cause significant morbidity and overt complications such as anemia [59, 60]. The relevance of non-falciparum species is thus increasingly recognized across Africa, particularly when considering malaria elimination goals [54]. Furthermore, a significant contribution of non-falciparum isolates to Plasmodium spp. infections among adults was observed, highlighting the need for the NMCP to update national policies and practices to target all species appropriately.

Potent testing tools should be considered to efficiently address Plasmodium spp. infections among adults

Conventional microscopy could not be applied to detect and identify Plasmodium spp. in this series. This would have required highly qualified and well-trained microscopists, who were lacking on the site at the time of this study, as it is often observed in low-resource settings [55, 61]. Instead, a locally enforced HRP2-based RDT in accordance with national policies was used [25]. RDTs are lateral-flow immunochromatographic devices that had been developed to overcome limitations of conventional microscopy [61]. Unlike microscopy, results obtained with RDTs vary less between examiners and remain as consistent in population surveys as in routine testing, without requiring advanced technical training [61, 62]. Currently available RDTs can achieve a sensitivity that is similar to that of good field microscopy—that is, ∼100 parasites per μl of blood in approximately 5 μl of whole blood [62]. Obviously, microscopy in research settings or reference laboratories may provide greater sensitivity than field microscopy for detecting Plasmodium spp.; nevertheless, its detection threshold generally remains > 10 parasites per µl of blood [62]. Meanwhile, infections with Plasmodium spp. commonly exhibit very low parasitaemias among asymptomatic adults in endemic areas and raise significant diagnostic challenges, especially when involving non-falciparum species [55, 58]. Mixed infections may be masked by more visible concomitant P. falciparum and would go unnoticed under microscopy and RDTs [13, 55, 58]. To circumvent these potential diagnostic limitations, an established nested PCR that can detect the four major Plasmodium spp. (i.e., P. falciparum, P. malariae, P. ovale, and P. vivax) with high sensitivity and specificity was remotely applied [34]. Subsequently, regardless of the species detected, an inadequate agreement was observed between HRP-2-based RDT and nested PCR. This likely reflects a low sensitivity due to high detection thresholds of the RDT used, particularly since nested PCR detected almost twice as many infections, including for P. falciparum. Marginal false-negative results with RDT could be due to a functional deletion of the HRP2 antigen existing in the DRC [63] and possibly to the prozone effect [63]. Conversely, false-positive results were also observed (in ~ 25% of positive RDT results) and can be explained by persistent HRP2 antigenaemia following resolved infections [64] or by cross-reaction with other diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [65]. Overall, these findings suggest poor adequacy of HRP-2-based RDT for community surveys of Plasmodium spp. among adults. To effectively address infected adults in communities, the NMCP should take our results into account and consider updating its diagnostic policies which still rely primarily on HRP-2-based RDTs. Microscopy would have performed similarly to RDTs because nested PCR is known to detect approximately twice as many infections as microscopy in community surveys [13, 62]. Nested PCR methods have been acknowledged along quantitative PCR and nucleic acid sequence-based amplification for highly sensitive diagnosis of Plasmodium spp. in research settings [13]. These molecular methods can, in theory, detect parasitaemias as low as one gene copy per reaction or a single parasite in the blood sample [13]. Molecular detection tools should therefore be integrated into interventions and epidemiological measures to potentiate malaria control and elimination efforts targeting adults.

Hosts' age profile and economic status may help optimize future interventions against Plasmodium spp. infections among asymptomatic adults

Addressing asymptomatic adults infected with Plasmodium spp. at community level in endemic areas requires a multi-pronged approach that goes beyond treating clinical cases. Strategies such as mass screening, mass or targeted drug administration or community engagement campaigns can be implemented. The logistical and financial burden of such mass interventions logically requires defining the population categories presenting the highest risks of infection to optimize the allocation of resources. In this regard, adults belonging to the “most economically disadvantaged” households were most exposed to Plasmodium spp. infections, whether P. falciparum or non-falciparum species. In accordance with this observation, existing evidence show that malaria affects the poorest categories of the population, being both a consequence and a cause of poverty and inequalities [3, 4]. Additionally, males were found with twice the risk of non-falciparum infections compared to females. P. falciparum infections were also more prevalent in males, although without reaching statistical significance. Evidence from school-age children and adults has long suggested this sex-based dimorphism in P. vivax and P. falciparum infections, often escribed to differences in exposure [66,67,68]. Likewise, sex differences in exposure or responses to diseases exist also for other pathogens [69, 70]. Beyond differential exposure, males have also been shown to clear more slowly asymptomatic P. falciparum infections than females, reflecting biological sex-based differences during host-parasite interactions and acquired immunity [71]. Hormonal differences, notably testosterone, would play a role in these sex-related immunological differences in Plasmodium spp. infections [72, 73]. However, further research is needed in this area to fully uncover the underlying mechanisms of these gender disparities. Furthermore, increasing the age of individuals by one year reduced the probability of infections by 1–2% among adults. Plasmodium spp. therefore disproportionately infected people under the age of 20 and gradually declined with age. Similarly, the age-related prevalence of P. falciparum infections peaks in people aged 10–14 years and gradually declines at older ages in the Congolese population [28]. Anti-parasite immunity acquisition in adulthood, following progressive maturation of the immune system (as opposed to anti-disease immunity acquired from childhood with repeated exposures), may partially explain this age-exposure relationship [10, 11]. Besides potential differences in host-parasite interactions and acquisition of immunity, the risk trends observed in this work may also be explained by differences in exposure due to behavioral factors such as occupational activities (e.g. example, school, agriculture, or night work), drug use and compliance with preventive measures [12]. Overall, categories of adult with higher Plasmodium spp. infection risks (e.g., the most economically disadvantaged, men, young adults) were identified, setting priorities to design tailored interventions to reduce transmission and ultimately eradicate malaria from the study regions and possibly elsewhere in the DRC.

Study limitations

Several limitations of the present study should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, the community-based survey captured only adults from a specific location within a vast country. Children not included in the present study, who may also develop significant asymptomatic infections, should be considered in future investigations [20, 23]. Therefore, extrapolating our findings to any other context requires caution. Second, additional caution should be taken with the molecular methods used in this investigation, which may result in excessive positivity due to the persistence of parasite DNA left over from past infections [74]. Furthermore, conventional microscopy that could have provided information on blood parasite density, which is an important correlate of acquired immunity and transmission dynamics in the population, is sorely lacking [13]. Finally, this study is based in part on interviews and self-assessments which may involve significant information and memory biases.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding the above limitations, this study has the merit of drawing attention to Plasmodium infections in adults, an often-neglected aspect of malaria epidemiology in endemic countries such as the DRC. Obtained results show that asymptomatic adults are broadly infected with Plasmodium spp. While P. falciparum remains the main species infecting adults, a surprisingly high contribution of non-falciparum species was noted, notably with P. malariae and P. ovale. Infected adults thus provide a large reservoir of Plasmodium spp. transmission, significant diagnostic challenges, complex malaria control efforts, and impact on individual health. This underscores the need for increased awareness of Plasmodium spp. infected adults and non-falciparum malaria in the study area. Effective interventions tailored to the population studied can be designed by prioritizing the socio-economic categories identified as most relevant in this survey (i.e. age, gender, and economic level). Molecular methods rather than common RDTs should be considered for diagnostic goals during various interventions targeting infected adults. Further research is needed to expand knowledge on Plasmodium spp. infecting adults and to establish programmatic and effective elimination strategies.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated during this study are included in the published article and its additional file.

Abbreviations

- DRC:

-

Democratic Republic of Congo

- RDT:

-

Rapid diagnostic test

- NMCP:

-

National Malaria Control Program

- LLIN:

-

Long-lasting insecticide net

- MAP:

-

Malaria Atlas Project

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- HRP-2:

-

The Plasmodium falciparum histidine rich protein 2 antigen

- COX3:

-

Cytochrome c oxidase III

- AIC:

-

Akaike Information Criterion

- IQR:

-

Interquartile interval

- AMED:

-

The Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development

- JSPS:

-

The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science

References

WHO. World malaria report 2022. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022.

Ricci F. Social implications of malaria and their relationships with poverty. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2012;4:e2012048.

Gallup JL, Sachs JD. The economic burden of malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64:85–96.

Kayiba NK, Yobi DM, Devleesschauwer B, Mvumbi DM, Kabututu PZ, Likwela JL, et al. Care-seeking behaviour and socio-economic burden associated with uncomplicated malaria in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Malar J. 2021;20:260.

WHO. Global technical strategy for malaria 2016–2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

WHO. World malaria report 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

Chen I, Cooney R, Feachem RG, Lal A, Mpanju-Shumbusho W. The lancet commission on malaria eradication. Lancet. 2018;391:1556–8.

Monroe A, Williams NA, Ogoma S, Karema C, Okumu F. Reflections on the 2021 World malaria report and the future of malaria control. Malar J. 2022;21:154.

Miller LH, Baruch DI, Marsh K, Doumbo OK. The pathogenic basis of malaria. Nature. 2002;415:673–9.

White M, Watson J. Age, exposure and immunity. Elife. 2018;7:e40150.

Lindblade KA, Steinhardt L, Samuels A, Kachur SP, Slutsker L. The silent threat. asymptomatic parasitemia and malaria transmission. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2013;11:623–39.

Chen I, Clarke SE, Gosling R, Hamainza B, Killeen G, Magill A, et al. “Asymptomatic” malaria: a chronic and debilitating infection that should be treated. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1001942.

Bousema T, Okell L, Felger I, Drakeley C. Asymptomatic malaria infections: detectability, transmissibility and public health relevance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:833–40.

Heinemann M, Phillips RO, Vinnemeier CD, Rolling CC, Tannich E, Rolling T. High prevalence of asymptomatic malaria infections in adults, Ashanti Region, Ghana, 2018. Malar J. 2020;19:366.

Fogang B, Biabi MF, Megnekou R, Maloba FM, Essangui E, Donkeu C, et al. High prevalence of asymptomatic malarial anemia and association with early conversion from asymptomatic to symptomatic infection in a Plasmodium falciparum hyperendemic setting in Cameroon. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2022;106:293–302.

Duguma T, Tekalign E, Kebede SS, Bambo GM. Prevalence of asymptomatic malaria and associated factors among pregnant women in Ethiopia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Reprod Health. 2023;5:1258952.

Agaba BB, Rugera SP, Mpirirwe R, Atekat M, Okubal S, Masereka K, et al. Asymptomatic malaria infection, associated factors and accuracy of diagnostic tests in a historically high transmission setting in Northern Uganda. Malar J. 2022;21:392.

Hayuma PM, Wang CW, Liheluka E, Baraka V, Madebe RA, Minja DT, et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic malaria, submicroscopic parasitaemia and anaemia in Korogwe District, north-eastern Tanzania. Malar J. 2021;20:424.

Mvumbi DM, Bobanga TL, Melin P, De Mol P, Kayembe J-MN, Situakibanza HN-T, et al. High prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum infection in asymptomatic individuals from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Malar Res Treat. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5405802.

Andolina C, Rek JC, Briggs J, Okoth J, Musiime A, Ramjith J, et al. Sources of persistent malaria transmission in a setting with effective malaria control in eastern Uganda: a longitudinal, observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:1568–78.

Koepfli C, Robinson LJ, Rarau P, Salib M, Sambale N, Wampfler R, et al. Blood-stage parasitaemia and age determine Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax gametocytaemia in Papua New Guinea. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0126747.

Tadesse FG, Slater HC, Chali W, Teelen K, Lanke K, Belachew M, et al. The relative contribution of symptomatic and asymptomatic Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum infections to the infectious reservoir in a low-endemic setting in Ethiopia. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:1883–91.

Rek J, Blanken SL, Okoth J, Ayo D, Onyige I, Musasizi E, et al. Asymptomatic school-aged children are important drivers of malaria transmission in a high endemicity setting in Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2022;226:708–13.

Likwela JL. Lutte antipaludique en République Démocratique du Congo à l’approche de l’échéance des OMD: progrès, défis et perspectives. Rev méd Gd Lacs. 2014;3:149–55.

PNLP. Plan Stratégique National de Communication 2017–2020. Kinshasa, RD Congo: Ministère de la Santé Publique; 2017.

Ilunga H, Likwela J, Julo-Réminiac J-E, O’Reilly L, Kalemwa D, Lengeler C, et al. An epidemiological profile of malaria in the Democratic Republic of Congo. A report prepared for the Federal Ministry of Health, Democratic Republic of Congo, the Roll Back Malaria Partnership and the Department for International Development, UK. March 2014.

Deutsch-Feldman M, Brazeau NF, Parr JB, Thwai KL, Muwonga J, Kashamuka M, et al. Spatial and epidemiological drivers of Plasmodium falciparum malaria among adults in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e002316.

Deutsch-Feldman M, Parr JB, Keeler C, Brazeau NF, Goel V, Emch M, et al. The burden of malaria in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. J Infect Dis. 2021;223:1948–52.

Mitchell CL, Topazian HM, Brazeau NF, Deutsch-Feldman M, Muwonga J, Sompwe E, et al. Household prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, and Plasmodium ovale in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2013–2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e3966–9.

PNLP. Directives nationale de prise en charge du paludisme. Kinshasa: Ministère de la Santé Publique; 2017.

Tshonda JO, Kadima-Tshimanga B, Stroobant E, Shotsha DO, Simons E, Mukoko LK, et al. Un noeud gordien dans l’espace congolais. Tervuren: Musée Royal de l’Afrique centrale (MRAC); 2014.

WHO. Improving health system efficiency: Democratic Republic of the Congo: improving aid coordination in the health sector. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Kottek M, Grieser J, Beck C, Rudolf B, Rubel F. World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorolog Zeitschr. 2006;15:259–63.

Isozumi R, Fukui M, Kaneko A, Chan CW, Kawamoto F, Kimura M. Improved detection of malaria cases in island settings of Vanuatu and Kenya by PCR that targets the Plasmodium mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase III (cox3) gene. Parasitol Int. 2015;64:304–8.

Echeverry DF, Deason NA, Davidson J, Makuru V, **ao H, Niedbalski J, et al. Human malaria diagnosis using a single-step direct-PCR based on the Plasmodium cytochrome oxidase III gene. Malar J. 2016;15:128.

Abdulraheem MA, Ernest M, Ugwuanyi I, Abkallo HM, Nishikawa S, Adeleke M, et al. High prevalence of Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale in co-infections with Plasmodium falciparum in asymptomatic malaria parasite carriers in southwestern Nigeria. Int J Parasitol. 2022;52:23–33.

Wickham H, Wickham MH. Package ‘tidyverse’. See. 2019:1–5.

Pfeffer DA, Lucas TCD, May D, Harris J, Rozier J, Twohig KA, et al. malariaAtlas: an R interface to global malariometric data hosted by the Malaria Atlas Project. Malar J. 2018;17:352.

Larsson J. eulerr: area-proportional Euler diagrams with ellipses. 2018.

Nakazawa M, Nakazawa MM. Package ‘fmsb’. See 2019. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/fmsb/index.html.

Husson F, Josse J, Le S, Mazet J, Husson MF. Package ‘factominer.’ An R Package. 2016;96:698.

Kassambara A, Mundt F. Package ‘factoextra’. Extract and visualize the results of multivariate data analyses 2017, 76.

Devleesschauwer B, Torgerson PR, Charlier J, Levecke B, Praet N, Dorny P, Berkvens D, Speybroeck N. Package ‘prevalence’. 2013.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74.

McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med. 2012;22:276–82.

Brown LD, Cai TT, DasGupta A. Interval estimation for a binomial proportion. Stat Sci. 2001;16:101–33.

Sendor R, Banek K, Kashamuka MM, Mvuama N, Bala JA, Nkalani M, et al. Epidemiology of Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale spp. in Kinshasa Province Democratic Republic of Congo. Nat Commun. 2023;14:6618.

Brazeau NF, Mitchell CL, Morgan AP, Deutsch-Feldman M, Watson OJ, Thwai KL, et al. The epidemiology of Plasmodium vivax among adults in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Nat Commun. 2021;12:4169.

Mitchell CL, Brazeau NF, Keeler C, Mwandagalirwa MK, Tshefu AK, Juliano JJ, et al. Under the radar: epidemiology of Plasmodium ovale in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. J Infect Dis. 2021;223:1005–14.

Howes RE, Reiner RC Jr, Battle KE, Longbottom J, Mappin B, Ordanovich D, et al. Plasmodium vivax transmission in Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004222.

Twohig KA, Pfeffer DA, Baird JK, Price RN, Zimmerman PA, Hay SI, et al. Growing evidence of Plasmodium vivax across malaria-endemic Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007140.

Ilunga HK, Likwela JL, Julo-Réminiac J-E, O’Reilly L, Kalemwa D, Lengeler C, et al. An epidemiological profile of malaria in the Democratic Republic of Congo. A report prepared for the Federal Ministry of Health, Democratic Republic of Congo, the Roll Back Malaria Partnership and the Department for International Development. Glasgow, UK, 2014. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/236199/

Nundu SS, Culleton R, Simpson SV, Arima H, Muyembe JJ, Mita T, et al. Malaria parasite species composition of Plasmodium infections among asymptomatic and symptomatic school-age children in rural and urban areas of Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Malar J. 2021;20:389.

Betson M, Clifford S, Stanton M, Kabatereine NB, Stothard JR. Emergence of non-falciparum Plasmodium infection despite regular artemisinin combination therapy in an 18-month longitudinal study of Ugandan children and their mothers. J Infect Dis. 2018;217:1099–109.

Gimenez AM, Marques RF, Regiart M, Bargieri DY. Diagnostic methods for non-falciparum malaria. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:681063.

McKenzie FE, Jeffery GM, Collins WE. Plasmodium malariae infection boosts Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte production. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:411–4.

Bousema JT, Drakeley CJ, Mens PF, Arens T, Houben R, Omar SA, et al. Increased Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte production in mixed infections with P. malariae. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:442–8.

Mueller I, Zimmerman PA, Reeder JC. Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale—the ‘bashful’malaria parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2007;23:278–83.

Langford S, Douglas NM, Lampah DA, Simpson JA, Kenangalem E, Sugiarto P, et al. Plasmodium malariae infection associated with a high burden of anemia: a hospital-based surveillance study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004195.

Douglas NM, Lampah DA, Kenangalem E, Simpson JA, Poespoprodjo JR, Sugiarto P, et al. Major burden of severe anemia from non-falciparum malaria species in Southern Papua: a hospital-based surveillance study. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001575.

Wambani J, Okoth P. Impact of malaria diagnostic technologies on the disease burden in the sub-Saharan Africa. J Trop Med. 2022;2022:7324281.

Bell D, Wongsrichanalai C, Barnwell JW. Ensuring quality and access for malaria diagnosis: how can it be achieved? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:682–95.

Gillet P, Mori M, Van Esbroeck M, Ende JVd, Jacobs J. Assessment of the prozone effect in malaria rapid diagnostic tests. Malar J. 2009;8:271.

Plucinski MM, Dimbu PR, Fortes F, Abdulla S, Ahmed S, Gutman J, et al. Posttreatment HRP2 clearance in patients with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J Infect Dis. 2018;217:685–92.

Lee J-H, Jang JW, Cho CH, Kim JY, Han ET, Yun SG, Lim CS. False-positive results for rapid diagnostic tests for malaria in patients with rheumatoid factor. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:3784–7.

Abdalla SI, Malik EM, Ali KM. The burden of malaria in Sudan: incidence, mortality and disability–adjusted life–years. Malar J. 2007;6:97.

Pathak S, Rege M, Gogtay NJ, Aigal U, Sharma SK, Valecha N, et al. Age-dependent sex bias in clinical malarial disease in hypoendemic regions. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35592.

Molineaux L, Gramiccia G. The Garki project: research on the epidemiology and control of malaria in the Sudan savanna of West Africa. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1980.

Nhamoyebonde S, Leslie A. Biological differences between the sexes and susceptibility to tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(Suppl 3):S100–6.

Fischer J, Jung N, Robinson N, Lehmann C. Sex differences in immune responses to infectious diseases. Infection. 2015;43:399–403.

Briggs J, Teyssier N, Nankabirwa JI, Rek J, Jagannathan P, Arinaitwe E, et al. Sex-based differences in clearance of chronic Plasmodium falciparum infection. Elife. 2020;9:e59872.

Delić D, Ellinger-Ziegelbauer H, Vohr H, Dkhil M, Al-Quraishy S, Wunderlich F. Testosterone response of hepatic gene expression in female mice having acquired testosterone-unresponsive immunity to Plasmodium chabaudi malaria. Steroids. 2011;76:1204–12.

Vom Steeg LG, Flores-Garcia Y, Zavala F, Klein SL. Irradiated sporozoite vaccination induces sex-specific immune responses and protection against malaria in mice. Vaccine. 2019;37:4468–76.

Homann MV, Emami SN, Yman V, Stenström C, Sondén K, Ramström H, et al. Detection of malaria parasites after treatment in travelers: a 12-months longitudinal study and statistical modelling analysis. EBioMedicine. 2017;25:66–72.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the community from the Health District of Lukelenge (DRC) for their participation in this study. We are grateful to Ms. Mayumi Fukui and Ms. Ikuko Kusuda (Department of Parasitology, Graduate School of medicine, Osaka Metropolitan University) who helped in running the PCR assays.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI under Grant Number JP18KK0454 and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant numbers JP21wm0125003 and JP19fm0208020 (all to Yasutoshi Kido).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YK, NS, NKK, YN, and TKE conceived the study. NKK and TKE wrote the study protocol. NKK, YN and TKE did the data analyses and made the figures. NKK, YN, and ETK wrote the initial manuscript. All co-authors made a major contribution in revising the manuscript. They read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All study subjects provided their informed consent for inclusion before participation in the study. A formal consent was thus obtained written. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Boards of the University of Mbujimayi in the DRC (N#34/MREC/UM/ETK/GDT/2018).

Consent for publication

All co-authors have read and approved this manuscript for publication.

Competing interests

Authors have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

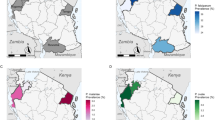

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Surveys assessing P. falciparum infections across Africa. These maps display prevalence estimates of P. falciparum infections through the entire Africa (A) and through the DRC (B) based on the pulled data sources provided by the Malaria Atlas Project (MAP) (https://malariaatlas.org/pf-pv-cubes-2019/). Color palettes reflect the relative prevalence predicted at each site. The Lukelenge health zone where the current survey was conducted is indicated. Table S1. Baseline socio-demographic characteristics of the study population. Table S2. Self-reported history of putative clinical malaria episodes and use of preventive measures in the study population. Table S3. Qualitative agreement between assays for the detection of P. falciparum malaria in the study population. Table S4. Qualitative agreement between assays for the detection of non-falciparum malaria in the study population

Additional file 2.

Survey Questionnaire

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kayiba, N.K., Nitahara, Y., Tshibangu-Kabamba, E. et al. Malaria infection among adults residing in a highly endemic region from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Malar J 23, 82 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-024-04881-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-024-04881-7