Abstract

Background

The Malaria Frontline Project (MFP) supported the National Malaria Elimination Program for effective program implementation in the high malaria-burden states of Kano and Zamfara adapting the National Stop Transmission of Polio (NSTOP) program elimination strategies.

Project implementation

The MFP was implemented in 34 LGAs in the two states (20 out of 44 in Kano and all 14 in Zamfara). MFP developed training materials and job aids tailored to expected service delivery for primary and district health facilities and strengthened supportive supervision. Pre- and post-implementation assessments of intervention impacts were conducted in both states.

Results

A total of 158 (Kano:83; Zamfara:75) and 180 (Kano:100; Zamfara:80) healthcare workers (HCWs), were interviewed for pre-and post-implementation assessments, respectively. The proportions of HCWs with correct knowledge on diagnostic criteria were Kano: 97.5% to 92.0% and Zamfara: 94.7% to 98.8%; and knowledge of recommended first line treatment of uncomplicated malaria were Kano: 68.7% to 76.0% and Zamfara: 69.3% to 65.0%. The proportion of HCWs who adhered to national guidelines for malaria diagnosis and treatment increased in both states (Kano: 36.1% to 73.0%; Zamfara: 39.2% to 67.5%) and HCW knowledge to confirm malaria diagnosis slightly decreased in Kano State but increased in Zamfara State (Kano: 97.5% to 92.0%; Zamfara: 94.8% to 98.8%). HCWs knowledge of correct IPTp drug increased in both states (Kano: 81.9% to 94.0%; Zamfara: 85.3% to 97.5%).

Conclusion

MFP was successfully implemented using tailored training materials, job aids, supportive supervision, and data use. The project strategy can likely be adapted to improve the effectiveness of malaria program implementation in other Nigerian states, and other malaria endemic countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria, a preventable and treatable disease, is a major cause of morbidity and mortality globally. An estimated 241 million cases of malaria occurred worldwide in 2020, of which 228 (95%) million cases were from the African region. African children under 5 years of age are the most vulnerable group accounting for 77% of all malaria deaths worldwide [1].

Nigeria has year-round malaria transmission, with 97% of its population at risk of malaria infection, transmission in the northern part of the country is however highly seasonal [2]. According to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2021 malaria report, Nigeria contributed 27% of the 241 million global malaria cases [1]. In the 2015 Nigeria Malaria Indicator Survey, 60% of outpatient visits to health facilities, 30% of childhood deaths, and 25% of infant mortality are attributed to malaria [3]. Under-five children experience an average of 2–4 episodes per year and account for as much as 90% of national malaria mortality with 36% attributable to malaria [4]. Nigeria’s high under-five malaria mortality is largely attributable to a health financing system that leaves many individuals uninsured, resulting in high out-of-pocket (OOP) medical expenditure that discourages care-seeking behaviour. The country accounts for the lowest rates of care-seeking for suspected cases of under-five malaria in the world accounting for less than 20% of all under-fives with fever being brought to health facilities for clinical consultation and parasitological testing [4]. Furthermore, malaria has been shown to account for over 40% of the total monthly curative healthcare costs incurred by households in Nigeria as compared to a combination of other illnesses; the cost of treating malaria and other illnesses depleted 7.03% of the monthly average household income, and treatment of malaria cases alone contributed 2.91% of these costs [5].

In Nigeria, the burden of malaria varies by geopolitical zones and states, with the northwestern states having the highest burden [6, 7]. The 2015 National Malaria Indicator Survey (MIS) showed the national average of malaria parasitemia by rapid diagnostic test (RDT) for children under five years old was 45%, but Kano and Zamfara States had parasitemia of 60.2% and 69.9% respectively [6].

The National Malaria Elimination Program (NMEP) implemented the National Malaria Strategic Plan 2014–2020 with [3] outlined targets to ensure transition from malaria control to malaria elimination.. The plan has multiple interventions based on WHO recommendations that are being scaled up for population impact. The interventions are Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS) across some geographical regions in the northern part of the country, universal coverage of Long Lasting Insecticidal Nets (LLIN), strategic use of larval source management (larvicide and environmental management), increased coverage of Intermittent Preventive Treatment (IPTp) with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) for malaria prevention during pregnancy, strategic deployment of seasonal malaria chemoprevention in the northern part of the country (an area of high seasonal malaria transmission), and provision of prompt access to effective malaria case management with emphasis on parasitological confirmation before treatment [3]. Despite concerted efforts in implementing these interventions, malaria has continued to endanger lives, with resultant increase in morbidity and mortality amongst the population and socio-economic impact [3, 8].

In July 2012, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the African Field Epidemiology Network (AFENET) established the National Stop Transmission of Polio program (NSTOP) to strengthen the Nigeria Polio Eradication Program at the subnational (state and LGA) levels and strengthen the routine immunization program [9]. NSTOP staff provide technical support to implement the National Polio Eradication Emergency Plan in polio high-risk areas, strengthen routine immunization, and improve maternal and child health indices [9, 10]. NSTOP staff also respond to communicable diseases outbreaks like measles and rubella, across states in Nigeria.

In 2016, the CDC established the Malaria Frontline Project (MFP) in collaboration with AFENET/NSTOP and NMEP to support the elimination of malaria in Nigeria using the NSTOP structure. The project was implemented in the high malaria burden states of Kano and Zamfara. These states (Fig. 1) were selected because of their high malaria burden as documented in the 2015 MIS and their state governments’ commitment to their malaria elimination programs.

The objectives of the project were to strengthen the technical capacity of healthcare workers (HCWs) to implement malaria interventions (diagnosis, treatment, and prevention services), strengthen malaria surveillance and facilitate evidence-based decision making, and improve malaria commodities distribution to health facilities using routine health facility data. This paper describes MFP implementation and its contributions to malaria control programs in health facilities in Kano and Zamfara States, Nigeria.

Project areas

The project states are in the northwest geopolitical zone of Nigeria. Kano state has 44 local government areas (LGAs) and 484 political wards, with 14 LGAs and 147 wards in Zamfara state. The projected 2016 population for Kano and Zamfara states are 13,076,892 and 4,515,427 respectively [11]. MFP was implemented in 20 high-burden malaria LGAs out of the 44 LGAs in Kano state, and the entire 14 LGAs in Zamfara state (Fig. 1). In Kano state, the total number of health facilities in the project area was 726, of which 575 are publicly owned and 151 privately owned. Primary Health Care (PHC) facilities are 608 (83.7%), secondary facilities are 116 (16.0%) and tertiary facilities are two (0.3%). Zamfara state has 739 health facilities of which 713 are publicly owned and 26 are private. There are 715 (96.8%) PHCs, 22 (3.0%) secondary facilities and two (0.3%) are tertiary [12]. Pre-implementation and implementation activities of the Malaria Frontline Project (Fig. 2).

Baseline project assessment

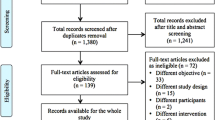

A baseline assessment was conducted (July – August 2016) before commencing MFP implementation. A modified President’s Malaria Initiative protocol for malaria intervention assessment in Nigeria was the basis for our assessments [13]. The baseline assessment data were obtained from (1) Interviews of primary and secondary facilities’ healthcare workers about their knowledge and practices of malaria case management and (2) exit interviews of health facility clients assessing malaria case management, LLIN distribution, and IPTp practices. Twenty-three PHCs from the project LGAs and 29 General Hospitals (GHs) in Kano State, and 23 PHCs and 16 GHs in Zamfara State were surveyed during the baseline assessment.

Healthcare workers interviews

Two HCWs at each selected PHC (officer-in-charge and staff attending to patients) and at secondary health facilities, also known as General Hospitals (head of the out-patient department and staff attending to patients) were interviewed using a structured questionnaire. If the heads of the out-patient department do not consult with patients, then two HCWs attending to patients were interviewed about knowledge and practices regarding malaria case management.

Client exit interviews

Client exit interviews (5 clients in each selected PHC facility) were conducted using questionnaires to assess client responses regarding HCWs’ adherence to national malaria case management guidelines, including both clinical and parasitological diagnostic confirmation of malaria and treatment with Artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT). Interviewees were clients who came to the facility due to fever. If the client with fever was a child, the interview was conducted with the adult caregiver who brought the child to the facility. After interviewing a client, the next client to exit the PHC with fever as the main complaint was selected and interviewed until a total of 5 clients were interviewed during the facility visit.

Pregnant women in their second and third trimesters exiting the facility after antenatal care service were interviewed about receiving SP and the adherence of HCWs to the guidelines of SP administration under directly observed therapy. A total of five pregnant women were interviewed consecutively at each facility.

Details of the methodology and findings of the baseline assessment is as referenced [14].

Project implementation approach

The MFP worked within the organogram of NSTOP at the national and sub-national levels, with two staff at headquarters, one at each state program, and one at each LGA totaling 38 MFP staff (Fig. 3). The project was modelled after the NSTOP implementation strategy. It centered on health system strengthening through capacity building of the health workforce at all levels. Assessments were conducted in the project states to collect baseline and end-line information of the state malaria control activities regarding case management, surveillance, malaria in pregnancy, and program management, with focus on leadership and coordination activities. Findings from the baseline assessment guided the MFP to adapt the NSTOP three-pronged training strategy. The three-prong strategy included classroom didactic training taught using structured lessons, post-training group work assignments with case studies, and health facility supportive supervisory visits conducting on-the-job training for challenged facilities. During the field practicum, trainees were given assignments to report back for the next training session one to two months later.

Training strategy

Training materials were developed for different malaria control themes based on the findings from the baseline assessment. Training content was oriented towards the expected services to be delivered by HCWs at PHC or hospital at ward or LGA level respectively. The training used cascade approach based on the levels of healthcare administration in the country. The project’s training strategy comprises a didactic and post-training assignment (field work) components. A National training of trainers was conducted in Abuja, FCT for state level officers for each thematic modules, this was followed up with a state level training in Kano and Zamfara state for LGA level officers based on the thematic areas of interest facilitated by trained state level officers. A cascade level training for healthcare workers at the health facility level facilitated by trained LGA level officers with a post-training assignment as field work over some weeks which will later be assessed during the conduct of a new thematic modular training. The categories of trainees for the various thematic areas clearly stated. (Tables 1 and 2).

Administratively, a state consists of LGAs and an LGA consists of wards, PHCs are situated in wards. Cascade training approach is a step-down training by a level to the next level below like national to state, state to LGA, LGA to ward and ward to the health facility level. Facilitators from a higher-level train the staff of the level next below them. To minimize interruption of service delivery, PHC training materials are adapted for one-day training with tailored must-know content essential for optimal health service delivery. The master trainers deliver the PHC level modular training to health workers in clusters at the ward level.

NMEP staff served as facilitators. An in-class didactic training was organized for the LGA health team and MFP NSTOP LGA officers (NSLOs), who were given post-training field assignments of four-to-six weeks duration to facilitate practical application of the classroom learning. Supportive supervision for health facility staff from LGA to facility levels was strengthened in collaboration with the state Malaria Elimination Programs and LGA team. The health authorities provided logistic support during the project that enabled the supervisory team to conduct more scheduled supportive visits than previously, as state and LGA activities permitted. During the visits, on-the-job training and mentoring for the facility staff was conducted where necessary if knowledge deficits were identified. An important component of the MFP strategy was the paired training of NSLOs with LGA health teams (especially the LGA malaria focal person) and the combined field visits. The paired training provided opportunities for the exchange of ideas and transfer of skills between the two groups and improvement in work relationships. Thematic trainings began in October 2016, and field implementation of the project at the LGA level commenced in January 2017. Supportive supervision with an updated supervision checklist commenced in April 2017.

Training modules

Five modular training curricula were developed and implemented with NSLOs over a period of 36 months. The first training module focused on an “overview of malaria”. Because the NSLOs did not necessarily have health backgrounds, it was important to orientate them on malaria as a public health problem and introduce the NSLOs to the operation of the malaria program within the state.

To help strengthen health facility and LGA technical capacity, additional thematic training modules were developed on 2) malaria diagnosis and treatment, 3) prevention and treatment of malaria in pregnancy, 4) malaria surveillance, and 5) data management and analysis for health information systems. Refresher courses on these themes were organized at different times during the project implementation. Trainings, refresher trainings, and the number of persons trained are reflected in Tables 1 and 2.

Training and refresher training was conducted across the project (20) LGAs in Kano State, and 14 LGAs in Zamfara state with cascade level trainings done. LGA level officers (PHC Coordinators, Malaria LGA officers, M&E officers, Maternal and Child Health officers, and Malaria NSLOs) were participants in the state level training. Trained LGA level officers later then conduct a 1-day cascade level training to health facility officers. In 2019, Kano State health authorities requested for the expansion of the project to all LGAs in the state so further trainings were conducted for the remaining 24 LGAs. (Table 1).

Case management and malaria in pregnancy

Training materials for malaria case management and malaria in pregnancy were based on the national guidelines tailored to the HCWs expected service provision at the PHC and secondary health facility levels. Job aids for the diagnosis and treatment of uncomplicated malaria and the prevention of malaria in pregnancy algorithm, including IPTp, were developed and distributed to all health facilities in the project states to routinely refresh HCW knowledge.

Surveillance and data analysis for decision making

Health facility data are recorded routinely using the national health management information system (NHMIS) forms and registers. Data from the health facilities are transferred to the monthly summary form (MSF) and submitted to the Monitoring and Evaluation officer of the LGA. This officer at the LGA collates the facility MSF and enter the data into the District Health Information System version 2 (DHIS2) platform. The baseline assessment conducted earlier in the project revealed major gaps in surveillance and data management with missing data, incorrect data summation, and lack of data analysis at facility and LGA levels. These findings informed the development of surveillance-specific training module for malaria data analysis and surveillance training of LGA and health facility staff.

A minimum number of malaria indicators for monitoring and comparison of program performance at the LGA, ward, and facility level were selected in collaboration with health authorities. The following indicators were selected at the facility level: outpatient febrile cases, febrile cases tested for malaria, test-positive cases given correct antimalaria treatment, antenatal care (ANC) attendees due for IPTp who were given SP, and pregnant women and children under five years old issued an LLIN. The training focused on the interpretation of data analyses, thereby facilitating the use of data for decision making and hel** to rectify problems at health facilities. During the project implementation, efforts were made to enhance the visibility of malaria data and increase its use to improve program performance. A Malaria Monitoring wall chart (Fig. 3) was developed and distributed to all health facilities, ward and LGA offices in the project states. Key elements of the wall chart summarizing monthly data were total outpatient visits, total ANC visits, and malaria in pregnancy, and LLIN uptake among children under five years and pregnant women. Key indicators on the wall chart were monitored for the purpose of initiating public health action. The chart helped users understand the malaria trends, adherence/non-adherence to national diagnosis and treatment guidelines, uptake of intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy, and LLIN uptake among pregnant women and children under five years. Gaps such as transcriptional, summarizing, and trans-positional errors were identified by HCWs at the facility and resolved before data entry into DHIS by LGA Monitoring and Evaluation Officer.

End-line project assessment

The end-line assessment was conducted after three-years of the project implementation (October – December 2019) using the same protocol for the baseline assessment [13, 14]. The baseline and end-line assessments used the same protocol to enable comparison of the findings except replacing LGAs not accessible due to security issues. During the end-line assessment, some health facilities that were not visited in both project states due to non-functionality and security concerns at the time of the baseline assessment were replaced and surveyed. A total of 24 PHCs and 36 GHs in Kano State, and 24 PHCs and 16 GHs in Zamfara State were surveyed during the end-line assessment. Supervisory checklist being filled by NSLOs during health facility supportive supervision provide information on proportion of health facilities giving ACT to malaria negative patients, pregnant women who received IPTp, stockout of SP, and use of analyzed data from malaria monitoring wall chart for decision making.

Data analysis

Descriptive analyses of frequencies and corresponding percentages of the baseline and end-line assessments were conducted for the health facility components. The merged dataset was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23 and Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 9.4. Trends of selected malaria indicators from 2017 to 2019 from supervisory reports are described.

Results

Healthcare workers interviews

A total of 158 (Kano: 83, Zamfara: 75) and 180 (Kano: 100, Zamfara: 80) HCWs were interviewed during the baseline and end-line assessments, respectively. Fifty-six percent of HCWs interviewed in the baseline assessment and 59% of those interviewed in the end-line assessment work at PHCs.

Client exit interviews

A total of 131 (Kano: 82, Zamfara: 49) and 978 (Kano: 667, Zamfara: 311) clients were interviewed during the baseline and end-line assessments, respectively. At ANCs, five pregnant women were interviewed consecutively at each facility.

HCWs’ knowledge of and adherence to national guidelines on malaria diagnosis and treatment

Knowledge

Correct diagnosis

Diagnostic criteria for malaria were defined as fever, other symptoms, and signs suggestive and parasitological confirmation of malaria.

Over 90% of the respondents in the baseline and end-line assessments knew the correct diagnostic criteria for malaria (Kano: 94.0% to 92.0%, respectively; Zamfara: 94.7% to 98.8%, respectively). In Kano State, the proportion of HCWs who responded that clinical diagnosis only was the diagnostic criteria of malaria increased in the end-line assessment (Kano: 2.5% to 8.0%) but in Zamfara State there was a decline of the proportion of HCWs who did not know the correct diagnostic criteria (Zamfara: 4.1% to 1.3%) (Table 3).

Treatment

Over 60% of respondents correctly identified Artemether-Lumefantrine as the first-line drug for uncomplicated malaria treatment at baseline and end-line (Kano: 68.7% to 76.0%, respectively; Zamfara: 69.3% to 65.0%, respectively) (Table 3).

HCW-reported adherence to guidelines

The proportion of HCWs who responded that they adhere to the national guidelines of clinical plus parasitological confirmation for malaria diagnosis and treatment with ACT showed improvement from baseline to end-line in both states (Kano: 36.1% to 73.0%; Zamfara: 39.2% to 67.5%) (Table 4).

The proportion of HCWs who reported they adhere to parasitological diagnosis of malaria (using RDT) in both states was high at baseline and increased at the end-line assessment (Kano: 96.4% to 100.0%; Zamfara: 94.7% to 100.0%).

The proportion of HCWs who used the recommended ACTs medicines for treatment of uncomplicated malaria was high between baseline and end-line (Kano: 95.2% to 96.0%; Zamfara: 98.7% to 97.5%) (Table 4).

Facilities supervisory visit reports from 2017–2019 showed declines in the proportions of health facilities that use ACT for treatment of malaria-negative patients (Kano: 2.6%, 1.5% and 1.1%; Zamfara: 1.9%, 0.5%, and 0.5%).

HCWs’ knowledge of Malaria treatment during pregnancy

Between baseline and end-line assessments, the proportion of HCWs with correct knowledge about treatment of uncomplicated malaria in the 1st trimester of pregnancy with quinine tablets according to the national guidelines increased in Kano (36.1% to 54.0%) but decreased slightly in Zamfara (25.3% to 23.8%). The proportion of HCWs with correct knowledge for treatment of uncomplicated malaria in 2nd and 3rd trimester with ACT increase in Kano state but less so in Zamfara state (Kano: 56.6% to 69.0%; Zamfara: 60.0% to 61.3%) (Table 5).

HCWs’ knowledge and practice of prevention of malaria during pregnancy

IPTp

There was an increase in the proportions of HCWs who knew the recommended medicine for IPTp in Kano (82.0% to 94.0%), and in Zamfara (85.3% to 97.5%). The proportion of healthcare workers who knew the time to commence IPTp decreased in Kano from 90.0% to 85.0%, with an increase in Zamfara from 78.7% to 82.1%. (Table 5). However, the proportion of pregnant women receiving IPTp under direct observation therapy (DOT) at ANC increased [Kano: 42.9% (6/14) to 92.7% (114/131); Zamfara: 0.0% (0/6) to 77.5% (79/140)]. In Kano State, 12 of 14 (85.7%) pregnant women had received one or more doses of IPTp at baseline, and 121 of 131 (92.4%) had received one or more doses at end-line. In Zamfara State, only one of six (16.7%) of pregnant women had received one or more doses at the time of the baseline assessment, but at the time of the end-line assessment 85 of 105 (81.0%) had received one or more doses of IPTp. During the conduct of the baseline assessment, some health facilities could not be visited because of security challenges and inaccessible terrain during the rainy season. These contributed to the small sample size of the clients we interviewed. Also, for some health facilities, days selected for the baseline assessments did not coincide with ANC days in facilities visited, resulting in low client turn out (Table 6).

Reports from health facility supportive supervisory visits from 2017–2019 showed an increase in the proportion of health facilities that provided IPTp services as DOT [Kano: 83.3%, 97.9%, 97.3%; Zamfara: 83.5%, 88.1%, 88.6%].

LLINs

The percentage of pregnant women who were provided with LLINs at ANC visits was 7.1% at baseline and 38.7% at end-line in Kano State, and 33.3% at baseline and 23.3% at end-line in Zamfara State (Table 7).

Client exit interviews: malaria testing

The proportion of febrile patients that clinicians requested malaria parasitological testing increased in both states (Kano:72.8% to 97.2%; Zamfara79.2% to 96.6%) and the proportions of patients tested were high in both states (Kano: 100% to 99.2%; Zamfara: 94.7% to 99.3%) (Table 8).

Health facility supervisory visit reports

Supervisory reports during the project period (2017–2019) based on the facility malaria monitoring wall chart (Fig. 4), showed unconfirmed febrile patient receiving ACT reduced [(Kano: 56 (2.6%), 41 (1.5%) and 30 (1.1%); Zamfara: 24 (1.9%), 8 (0.5%) and 10 (0.5%) (Fig. 5), IPTp for pregnant women given by direct observation of client (DOT) improved (Kano: 1908 (83.3%), 2756 (97.9%) and 2794 (97.3%); Zamfara: 1210 (83.5%), 1662 (88.1%) and 1883 (88.6%) (Fig. 6) and, the proportion of facilities using analyzed data for decision making also improved (Kano: 1874 (92.2%), 2615 (97.6%) and 2708 (98.3%); Zamfara: 922 (90.8%), 1556 (95.0%) and 1886 (97.7%) (Fig. 7).

Discussion

The MFP leveraged the success of the NSTOP program strategy to build capacity of HCWs in malaria case management, surveillance, and data management using the three-prong training strategy approach of didactic training, post-training assignments, and health facility supportive supervisory visits with on-the-job training and mentorship [9]. The content of the training materials was very much oriented to the expected services that is to be delivered at the facility level. There were improvements in some of the malaria control interventions. Improved case management practices reduced clinically diagnosed malaria cases, increased testing of all febrile cases before treatment, and improved use of data for decision making at all levels. Gaps from the baseline assessment were addressed through targeted interventions of conduct of thematic modular trainings and health facility supportive supervisory visits during project implementation and measured through the end-line.

One of the objectives of MFP is capacity building of HCWs at LGA, ward and health facility levels. The National Malaria Strategic Plan 2014–2020 recommends that, by 2020, all febrile persons seeking care should be tested for malaria to confirm or rule out a parasitological diagnosis. The national malaria guideline states that all fever cases should be tested by rapid diagnostic test (RDT) or microscopy [15, 16]. Prior to the implementation of MFP many health workers practiced presumptive diagnosis of malaria, which was contrary to the national recommendations for management of uncomplicated malaria aimed at mitigating the problem of misdiagnosis leading to mismanagement of suspected malaria cases [17,18,19]. Parasitological diagnosis is a component of malaria case management. Improper use of ACTs without confirmatory diagnosis will result in negative clinical and economic impact [20].

The thematic modular trainings, post-training assignments on malaria case management practices, provision of hard copies of a simplified diagnosis and treatment algorithm in the consulting room, and regular (as permitted by other activities) LGA health team supportive supervisory visits mostly driven by NSLOs and on-the-job mentoring are all contributing factors to improvements in health workers knowledge and adherence to national guidelines on malaria diagnosis and treatment.

The capacity building of HCWs in filling out the malaria monitoring wall chart improved data capturing using the monthly summary form and increased health facilities using analyzed data for decision making. All health facilities implemented the use of monitoring wall chart successfully. This provided an opportunity to use data for decision making at the health facility level. But it also improved data validation at that level before the data were transferred into monthly summary form. Data validation meetings provided another layer of data quality assurance such as correction of identified errors for the data aggregated using the MSF. The gaps such as transcriptional, summarizing, and trans-positional errors were identified and resolved before data entry into DHIS. Impact of the project as reflected in key malaria indicators, include declines in clinically diagnosed malaria cases and health facilities administering ACT to negative malaria patients.

The improved adherence by HCWs to national guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of malaria is similar to studies conducted in other states in the north west region of the country, which found the expectation of the patient to be given antimalarial treatment and HCWs’ prior receipt of training on malaria case management (both by governmental and non-governmental organizations) were predictors of using rapid diagnostic test results to guide treatment [21, 22]. Studies have shown that when HCWs practice evidence-based medicine most especially, testing fever cases before treatment, resources are conserved, selective pressure on ACT is reduced, and ultimately potential early resistance to anti-malarial medicines can be averted [23]. The majority of HCWs at PHCs in the MFP states were community health extension workers (CHEWs). Within the context of PHC settings in Nigeria, CHEWs play a major role in the provision of basic health care services and have a higher likelihood of adherence to defined guidelines through periodic trainings and re-trainings, as conducted by MFP with support from project states malaria programs and regular health facility supportive supervision and on-the-job mentoring. The study findings of improved adherence to national guidelines on diagnosis and treatment is similar to other studies that reported the relationship between adherence to test results and training [24, 25]. There was improvement in HCW’s knowledge about drugs for intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy (IPTp) using SP and, in Zamfara, about the time of commencement of IPTp. This was likely attributable to the development and distribution of a malaria-in-pregnancy algorithm as a job aid for frontline line workers providing ANC services in health facilities across the two project states. This finding is similar to a study conducted in south-west Nigeria [26] and in contrast to other studies [27, 28]. However, the coverage of IPTp was very low, not meeting the 2016 national target of 80%. This low coverage of IPTp is similar to the study conducted in south-west Nigeria in which late ANC bookings and stock out of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine were associated with the low IPTp uptake [29]. Another study in Malawi found low IPTp uptake was associated with number of ANC visits [30] It is important to conduct a detailed study of factors contributing to the low uptake of IPTp in the second and third trimesters to improve the protection of the pregnant woman and her unborn child. The stockout of SP for IPTp during the MFP implementation contributed to the low uptake, hence partners and state health authorities need to procure adequate amount of SP and have equitable distribution to health facilities.

The client exit interview confirmed the increase in HCWs’ requests for parasitological confirmation of diagnosis and the increased prescription of ACT to treat malaria cases. This finding was similar to a study conducted in North-Central Nigeria in which healthcare providers prescribe ACTs based on test results, and good knowledge of malaria diagnosis and treatment as a result of prior trainings on malaria case management [31]. This finding was in contrast with a study conducted in Ebonyi State, Nigeria [32] in which health workers had poor perceptions of RDTs as reflected in the level of reported wrong prescription practices, and in contrast with other studies [33, 34].

Furthermore, the improvement in clinician’s adherence to national guidelines on diagnosis and treatment can be likely attributed to the collaborative efforts of the national and state malaria programs, MFP, and other malaria implementing partners. With continued trainings and re-trainings, clinicians now appreciate giving feedback to their clients on test results and diagnosis. However, the occasional shortages of diagnostic kits and antimalarial drugs during the project implementation affected HCWs adherence to national guidelines when faced with stockouts. It will be good for the state to assure adequate supply of antimalarial commodities to all health facilities because currently some facilities are not supported by any partner, and the state government is unable to provide adequate commodities. Despite facility records showing high percentages of antimalarial drugs given to confirmed malaria patients, the findings from client exit interview show a moderate result. This could be due to antimalarial commodities stock at the time of the assessment or the need to check on data quality at the facility level. Regular supportive supervision by LGA team to facilities is an important contributing factor for health workers adherence to the national guidelines.

The MFP implementation experienced some limitations which however were addressed. There was high transfer or movement of HCWs between states, within state, and rotation to different departments after training by MFP. This was however addressed by regular advocacy and follow up visits to the State Primary Health Care Board/Agency for retention of service providers across supported health facilities in both project states. Also, MFP did not provide any malaria commodities in the project area, however worked with other malaria implementing partners in ensuring continuous and uninterrupted supply of malaria related commodities to supported health facilities. Sustainability of innovative approaches implemented during the project implementation have been institutionalized with the state and LGA health teams’ involvement and ownership. The conduct of ward level data validation as a peer-to-peer capacity building platform for service providers with the routine health facility supportive supervision and mentorship, and use of data at the health facility for decision making have greatly helped resulted in data quality improvement during and after the project’s implementation in Kano and Zamfara states. The approach provided the opportunity to validate data efficiently in much smaller groups compared to the previous LGA level data validation and it facilitated earlier submission of the data into DHIS2. The ward level data validation meeting was adopted by NSTOP for routine immunization program. NMEP planned to expand the project to other states but there have been lot of changes in the program hierarchy. Our findings are not generalizable to other settings because of the non-probability approach to sampling the study population and the absence of control health facilities.

Conclusion

MFP was successfully implemented in both Zamfara and Kano States using tailored training materials, job aids, and supportive supervision, contributing to improved HCWs knowledge and adherence to guidelines on malaria case management. The strategy used to implement this project can be adapted to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of malaria program implementation in other states in Nigeria as well as other malaria endemic countries, especially on the African continent. Building the capacity of health facility leads in basic data analyses and use of the data for management will improve the health delivery system at the lower levels of the health system.

State malaria programs should continue with political commitment for implementation of malaria interventions, continuous capacity building of HCWs on adherence to national guidelines, sustaining and improving health facility supportive supervisory visits, sustaining LGA monthly data analysis of key malaria indicators, and the production of malaria monitoring wall charts.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- NMEP:

-

National Malaria Elimination Program

- IRS:

-

Indoor Residual Spraying

- LLIN:

-

Long Lasting Insecticidal Nets

- IPTp:

-

Intermittent Preventive Treatment during Pregnancy

- SP:

-

Sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine

- MIS:

-

Malaria Indicator Survey

- RDT:

-

Rapid diagnostic test

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- MFP:

-

Malaria Frontline Project

- AFENET:

-

African Field Epidemiology Network

- NSTOP:

-

National Stop Transmission of Polio Program

- HCWs:

-

Healthcare workers

- LGAs:

-

Local Government Areas

- PHC:

-

Primary Health Care

- NSLOs:

-

NSTOP Local Government Officers

- NHMIS:

-

National Health Management Information System

- MSF:

-

Monthly summary form

- DHIS2:

-

District Health Information System version 2

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- GHs:

-

General Hospitals

- ACT:

-

Artemisinin-based combination therapy

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- SAS:

-

Statistical Analysis System

- DOT:

-

Direct observation therapy

- CHEWs:

-

Community health extension workers

References

World malaria report 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2021.

No Title . Available from: https://drive.google.com/file/d/19xdYLZq1NixqrksAqINXPMXpdT7fIhxM/view (accessed April 12, 2021)

Federal Ministry of Health. National Malaria Elimination Program. The National Malaria Strategic Plan: 2021 -2025. Nigeria . Available from: https://www.health.gov.ng

Dasgupta R., Mao W, Ogbuoji O. Addressing child health inequity through case management of under-five malaria in Nigeria: an extended cost-effectiveness analysis. Malar J . 2022;21(81). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-022-04113-w

Onwujekwe O, Uguru N, Etiaba E, Chikezie I, Uzochukwu B, Adjagba A. The Economic Burden of Malaria on Households and the Health System in Enugu State Southeast Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e78362.

National Malaria Elimination Programme (NMEP), National Population Commission (NPopC), National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), and ICF International. 2016. Nigeria Malaria Indicator Survey 2015. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NMEP, NPopC,.

National Population Commission [Nigeria] and ICF International. 2019. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. Rockville, Maryland, USA: National Population Commission and ICF International.

Malaria’s Impact Worldwide . 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/malaria_worldwide/impact.html

Waziri N, Ohuabunwo C, Nguku P, Ogbuanu I, Gidado S, Biya O, et al. Polio Eradication in Nigeria and the Role of the National Stop Transmission of Polio Program, 2012–2013. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(Suppl 1):S111–7.

Michael C, Waziri N, Gunnala R, Biya O, Kretsinger K, Wiesen E, et al. Polio Legacy in Action: Using the Polio Eradication Infrastructure for Measles Elimination in Nigeria—The National Stop Transmission of Polio Program. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(Suppl 1):S373–9.

National Bureau of Statistics. Demographic Statistics Bulletin. 2017.

Bala U, Ajumobi O, Umar A, Adewole A, Waziri N, Gidado S, et al. Assessment of health service delivery parameters in Kano and Zamfara States, Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res . 2020;20(874). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05722-4

MEASURE Evaluation, National Malaria Elimination Programme (NMEP), and the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI/Nigeria). 2017. Malaria implementation assessment in four Nigerian states: Full report. Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA: MEASURE Evaluation, NMEP, and PMI/Nigeria. Available from: https://www.measureevaluation.org/resources/publications/tr-17-191_en.html

Adewole A, Cash S, Umar A, Ajumobi O, Bala U, Waziri N, et al. Malaria Frontline Project: Pre-intervention Malaria Baseline Assessment in Kano and Zamfara States. PAMJ Suppl Artic. 2016;40(1):3.

FMOH. National Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Malaria 2011. Nigeria: Nigeria: Federal Ministry of Health; 2011.

WHO. Test, Treat, Track. Brochure. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

WHO. uidelines for the treatment of malaria, Vol. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

WHO. niversal access to malaria diagnostic testing: an operational manual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

Skarbinski J, Ouma P, Causer L, Kariuki S, Barnwell J, Alaii J. Effect of malaria rapid diagnostic tests on the management of uncomplicated malaria with artemether-lumefantrine in Kenya: A cluster randomized trial. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:919–26.

Na’uzo A, Tukur D, Sufiyan M, Adebowale A, Ajayi I, Bamgboye E, et al. Adherence to malaria rapid diagnostic test result among healthcare workers in Sokoto metropolis, Nigeria. Malar J . 2020;19(2). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-019-3094-2

Bamiselu O, Ajayi I, Fawole O, Dairo D, Ajumobi O, Oladimeji A, et al. Adherence to malaria diagnosis and treatment guidelines among healthcare workers in Ogun State. Nigeria BMC Public Health. 2016;16:828.

Reyburn H, Mbakilwa H, Mwangi R, Mwerinde O, Olomi R, Drakeley C. Rapid diagnostic tests compared with malaria microscopy for guiding outpatient treatment of febrile illness in Tanzania: randomized trial. BMJ. 2007;334:403.

Akinyode A, Ajayi I, Ibrahim M, Akinyemi J, Ajumobi O. Practice of antimalarial prescription to patients with negative rapid test results and associated factors among health workers in Oyo State. Nigeria Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:229.

Singlovic J, Ajayi I, Nsungwa-Sabiiti J, Siribie M, Sanou A, Jegede A. Compliance with malaria rapid diagnostic testing by community health workers in 3 malaria-endemic countries of sub-Saharan Africa: an observational study. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):276–82.

Ladi Akinyemi T, Amoran O, Ogunyemi A, Kanma-Okafor O, Onajole A. Knowledge and implementation of the National Malaria Control Programme among health-care workers in primary health-care centers in Ogin State. Nigeria J Clin Sci. 2018;15:48–54.

Onyeaso N, Fawole A. Perception and practice of malaria prophylaxis in pregnancy among health care providers in Ibadan. Afr J Reprod Heal. 2007;11:69–78.

Arulogun O, Okereke C. Knowledge and practices of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy among health workers in a southwest local government area of Nigeria. J Med Med Sci. 2012;3(6):415–22.

Adewole A, Fawole O, Ajayi I, Yusuf B, Oladimeji A, Waziri E, et al. Determinants of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria among women attending antenatal clinics in primary health care centers in Ogbomoso, Oyo State. Nigeria Pan African Med Journal. 2019;33:101.

Azizi S. Uptake of intermittent preventive treatment for malaria during pregnancy with Sulphadoxine-Pyrimethamine in Malawi after adoption of updated World Health Organization policy: an analysis of demographic and health survey 2015–2016. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:335. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08471-5.

Nkoka O, Chuang T, Chen Y. Association between timing and number of antenatal care visits on uptake of intermittent preventive treatment for malaria during pregnancy among Malawian women. Malar J . 2018;17(211). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-018-2360-z

Welle S, Ajumobi O, Dairo M, Balogun M, Adewuyi P, Adedokun B, et al. Preference for Artemisinin-based combination therapy among healthcare providers, Lokoja, North-Central Nigeria. Glob Heal Res Policy. 2019;4(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-018-0092-9

Obi I, Sabitu K, Ajayi I, Ajumobi O. Health worker’s perception of malaria rapid diagnostic test and factors influencing compliance with test results in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0223869. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223869.

Kyabayinze D, Asiimwe C, Nakanjako D, Nabakooza J, Counihan H, Tibenderana J. Use of RDTs to improve malaria diagnosis and fever case management at primary health care facilities in Uganda. Malar J . 2010;9:200. Available from: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-9-200

Mubi M, Kakoko D, Ngasala B, Premji Z, Peterson S, Bjorkman A. Malaria diagnosis and treatment practices following introduction of rapid diagnostic tests in Kibaha District, Coast Region. Tanzania Malar J BioMed Cent. 2013;12:293.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank NMEP, Kano and Zamfara State Governments, Kano, and Zamfara State Malaria Elimination Programs and partners, LGA Health teams, and service providers. We used Mendeley reference manager in this manuscript.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Funding

This study was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number (GH15-1612) 1U2GGH001635 funded by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through African Field Epidemiology Network to the National Stop Transmission of Polio Program. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AA*, OA, NW, AU, UB, SC, SPK and KA conceived the study idea. AA*, OA, NW, AU, UB, SG, GU, ES, II, AA, SC, SPK and KA participated in the study design, implementation, and analysis. AA*, OA, AU, UB, SC, SPK and KA wrote the manuscript. AA*, OA, AU, UB, SG, CA, BU, PN, PU, BM, MI, SC, JW, SPK, PM and KA reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approvals were obtained for both baseline and end-line assessments from Health Research Ethics Committee, Kano State Ministry of Health and Zamfara State Health Research Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health. This activity was reviewed by CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable U.S. federal law and CDC policy. § Verbal informed consent was approved by Health Research Ethics Committee, Kano State Ministry of Health and Zamfara State Health Research Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health. Verbal Informed Consent to participate in the study was obtained from adult clients, caregivers of child under 15 years of age and caregivers of ward aged 15–17 years. Assent to conduct the study was obtained from minors between the age of 15–17 years. Confidentiality was maintained throughout the assessment by using non-personal identifiers during data analysis. Data were available to only the NSTOP data management team.

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations as approved by the Kano and Zamfara States’ Institutional Review Boards, and CDC with applicable U.S. federal law and CDC policy.

The findings and conclusions in this presentation are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

§See the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services regulations for the protection of human subjects in research at 45 C.F.R. part 46, 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 U.S.C. §241(d); 5 U.S.C. §552a; 44 U.S.C. §3501 et seq.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Adewole, A., Ajumobi, O., Waziri, N. et al. Malaria Frontline Project: strategic approaches to improve malaria control program leveraging experiences from Kano and Zamfara States, Nigeria, 2016–2019. BMC Health Serv Res 23, 147 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09143-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09143-x