Abstract

Background

Adolescent malignant-bone tumor patients' fear of cancer recurrence is a significant psychological issue, and exploring the influencing factors associated with fear of cancer recurrence in this population is important for develo** effective interventions. This study is to investigate the current status and factors influencing fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) related to malignant bone-tumors in adolescent patients, providing evidence for future targeted mental health support and interventions.

Design

A cross-sectional survey.

Methods

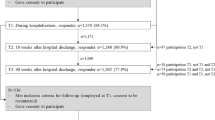

In total, 269 adolescent malignant-bone tumor cases were treated at two hospitals in Zhejiang Province, China from January 2023 to December 2023. Patients completed a General Information Questionnaire, Fear of Progression Questionnaire-Short Form (FoP-Q-SF), Family Hardiness Index (FHI), and a Simple Co** Style Questionnaire (SCSQ). Univariate and multivariable logistic regressions analysis were used to assess fear of cancer recurrence.

Results

A total of 122 (45.4%) patients experienced FCR (FoP-Q-SF ≥ 34). Logistic regression analysis analyses showed that per capita-monthly family income, tumor stage, communication between the treating physician and the patient, patient's family relationships, family hardiness a positive co** score, and a negative co** score were the main factors influencing FCR in these patients (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

FCR in malignant-bone tumor adolescent patients is profound. Healthcare professionals should develop targeted interventional strategies based on the identified factors, which affect these patients; hel** patients increase family hardiness, hel** patients to positively adapt, and avoid negative co** styles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malignant bone tumors occur in bones and appendant tissues. Early symptoms are atypical, but as the disease progresses, painful swelling, dysfunction, and even bony damage can develop at lesion sites [1]. Common malignant bone tumors include osteosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, and chondrosarcoma. Osteosarcoma is the most common malignant bone tumor; the disease has a 5-year survival rate of 60%–70%, with half of patients not surviving for more than 10 years, and a postoperative recurrence srate as high as 35% [2].

According to the Union for International Cancer Control, approximately 105,000 new bone cancer cases are recorded in adolescents every year: incidence rates are growing at approximately 1.5% per year, with the disease burden showing increasing trends year on year, concomitant with a significant economic impact on society [3]. In a study in a tertiary hospital in Bei**g [4], new malignant bone tumors were recorded at approximately 28,000 per year and were most common in adolescents, possibly due to vigorous bone growth [4]. Although lung, breast, and prostate cancers have the highest incidence rates, primary malignant bone tumors are the third leading cause of death in cancer patients under 20 years of age [5].

Due to the risk of local tumor recurrence and an unfavorable prognosis in adolescents after surgery, fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) has become a major psychological issue afflicting adolescent patients. One study reported that between 39 and 97% of cancer patients had varying degrees of FCR (average 73%), with moderate to high levels recorded in 22%–87% of cancer patients [6]. Low FCR is a normal and temporary psychological reaction, which helps patients be alert to disease progression and recurrence, and may facilitate positive and timely interventions. In contrast, high FCR levels can potentially impair psychological functioning, which in turn affects the quality of life of patients [7].

Currently, most FCR studies have focused on breast [8], prostate [9], lung [10], and ovarian cancer patients [11], but studies in adolescent malignant-bone tumor patients are rare. Therefore, by investigating FCR levels in these patients and analyzing influencing factors, we can begin to provide a theoretical basis for reducing FCR levels in this group.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

We recruited 269 adolescent malignant-bone tumor patients treated from January 2023 to December 2023 at two tertiary care hospitals in Zhejiang Province, China. Inclusion criteria: (1) patients diagnosed with malignant bone tumors by pathological tissue examination, who knew of their condition, and met 2020 World Health Organization (WHO) bone tumor classification rules [12]; (2) patients aged 10–19-years-old [1] (by following per under the age standard of adolescents stipulated by WHO; (3) patients with a degree of writing ability and verbal communication; and (4) patients aware of their condition and who voluntarily participated in the study.

Exclusion criteria: (1) patients with other cancers or more severe underlying diseases; (2) Patients with psychiatric diseases or cognitive disorders; (3) patients with a history of anxiety and depression; and (4) patients with severe hearing and speech disorders.

According to Logistic regression analysis requirements statistical requirements, the sample size had to be 5–10 times the number of variables. The total number of statistically analyzed variables in this study was 20 items (13 in the General Information Questionnaire; two in the Fear of Progression Questionnaire-Short Form (FoP-Q-SF); two in the Simple Co** Style Questionnaire (SCSQ); and three in the Family Hardiness Index (FHI). National and international studies revealed a 73% incidence of fear of cancer recurrence. In our study, Considering the 10% invalid questionnaire, the minimum sample size required for this study is: 20 × 5 x (1 + 10%) ÷ 73% = 150, and the maximum sample size is: 20 × 10 x (1 + 10%) ÷ 73% = 301. Investigators distributed 280 questionnaires to adolescents with malignant bone tumors and excluded 11 ineligible questionnaires. Therefore, 269 valid questionnaires were recovered with a valid return rate of 96.1%.

Procedures

The questionnaire consisted of four sections: demographic characteristics, FoP-Q-SF, FHI, and SCSQ. The investigators received consent from the hospital ethics committee before the investigation, contacted the head of the bone tumor department, the head nurse, and the charge nurse in advance, and obtained their full understanding and cooperation. Investigators explained the purpose and significance of the survey to patients and their families before radiotherapy or surgery and other treatments on the day of admission. All patients signed informed consent before starting to complete the questionnaire. Investigators instructed patients and family members on a “one-on-one” basis to complete questionnaires and objectively answer questions.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics

Questionnaires included 10 items: age, sex, place of residence, education, type of health insurance, religion, per capita monthly household income, tumor stage, and number of chemotherapy treatments.

FoP-Q-SF

This questionnaire was compiled by Mehnert [13], translated by Wu [14] in 2015, and is mainly used to measure and examine a patient’s fear of disease progression. The scale consists of two dimensions: physical health and social family. It contains 12 entries, using a 5-point Likert scale, with a total score of 12–60 points: one point for “never” and two points for “rarely,” two points for “sometimes” and one point for “never”, two points for “rarely” and two points for “sometimes”. The higher the score, the more serious a patient’s fear of disease progression is; i.e., a score ≥ 34. Such scoring establishes if a patient is experiencing psychological dysfunction. Cronbach’s α coefficient for the scale was 0.886, with α coefficients for physical health and social and family dimensions being 0.829 and 0.812, respectively [14].

FHI

This index was proposed by Mccubbin et al. [15] and revised in 2014 by Liu et al. [16]. It consists of three dimensions: responsibility, control, and challenge, with 20 entries. Entries 4–9, 11, 13, and 18 consider responsibility dimensions, entries 1–3, 10, 19, and 20 consider control dimensions, and entries 12, 14, and 17 consider challenge dimensions. A Likert 4-point scale is used, with “strongly disagree” scoring 1, “disagree” scoring 2, “agree” scoring 3, “strongly agree” scoring 4,. The scale includes “strongly disagree” (1 point), “disagree” (2 points), “agree” (3 points), and “strongly disagree” (4 points). “1–3”, “8”, “10”, “14”, “16”, “19”, and “20” (negative points), and “4”, “7”, “9”, “11”, “13”, and “15” (positive points), with a total score of 20–80 points. Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.803, with α coefficients for responsibility, control, and challenge dimensions being 0.764, 0.720, and 0.704, respectively [16].

SCSQ

** styles scale. Chin J Clin Psychol. 1998;13(02):53–4." href="/article/10.1186/s12889-024-18963-3#ref-CR17" id="ref-link-section-d162546270e649">17] developed the SCSQ, which consists of two dimensions, positive and negative co**, with 20 entries. The scale is rated on a 4-point Likert scale, 0 points for “do not take”, one point for “occasionally take”, two points for “sometimes take”, and three points for “often take” The positive co** dimension has 12 entries with scores ranging from 0–36 points. The negative co** dimension has 8 entries with scores ranging from 0–24 points. The higher the score on a dimension, the more prominent the adoption of a particular co** style by the patient. Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.90 [17].

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA). Categorical variables are described as frequency and percentage. To analyze quantitative data, we used the mean ± standard deviation to describe measures which conformed to a normal distribution. Multifactor analyses were performed using According to Logistic regression analysis requirements statistical requirements,. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (Approval No. I2023053).

Results

Patient information and characteristics

We recruited to 269 patients to this study; 156 males and 113 females. 122 patients reported experiencing FCR. Compared with those in the non-FCR group, respondents with fear of cancer recurrence tended to have lower family per capita monthly income and shorter course of disease. Patient characteristics are shown (Table 1).

FHI, and SCSQ scores in patients

A total of 122 (45.4%) patients experienced FCR (FoP-Q-SF ≥ 34). The mean FHI score was 57.88 ± 5.01, with 60.23 ± 4.14 in the non-FCR group and 55.00 ± 4.48 in the FCR group. The mean positive co** style score was 18.14 ± 3.44, with 19.30 ± 3.30 in the non-FCR group and 16.72 ± 3.07 in the FCR group. The mean negative co** style score was 14.00 ± 2.32, with 13.12 ± 2.16 in the non-FCR group and 15.07 ± 2.05 in the FCR group.

Univariate analysis of factors influencing FCR in patients

Univariate analyses showed that per capita monthly family income, disease duration, tumor stage, communication between the treating physician and the patient, and patient's family relationships, and were influential FCR factors in patients (P < 0.05). No difference in other demographic characteristics, including age, gender/sex, place of residence, education level, and payment method of medical expenses marital status, number of chemotherapy sessions was, number of hospitalizations per year observed between the two groups (Table 1).

Multifactorial analysis of factors influencing FCR in patients

The scale independent variable assignments are shown in Table 2. Logistic regression analysis revealed that 3000 ~ 5000 yuan (OR = 0.399, 95%CI: 0.171 ~ 0.929, P = 0.031) and > 5000 yuan (OR = 0.320, 95%CI: 0.114 ~ 0.900, P = 0.031), very satisfactory communication (OR = 0.202, 95%CI: 0.071 ~ 0.578, P = 0.003), good relationships (OR = 0.245, 95%CI: 0.092 ~ 0.658, P 0.005) and very good relationships (OR = 0.076, 95%CI: 0.026 ~ 0.225, P < 0.001), family Hardiness Indexand (OR = 0.734, 95%CI: 0.660 ~ 0.815, P < 0.001), and positive co** style (OR = 0.788, 95%CI: 0.692 ~ 0.898, P < 0.001) were all associated with lower level of FCR. Tumor stage IV (OR = 4.965, 95%CI: 1.135 ~ 21.731, P = 0.033), and negative co** style (OR = 1.442, 95%CI: 1.182 ~ 1.760, P < 0.001) were associated with higher level of FCR (Table 3).

Discussion

A higher incidence of FCR in adolescent patients with malignant bone tumors

Most recent studies have focused on FCR in patients with breast [27]. Among them, the incidence of fear of cancer recurrence was higher in patients with general communication than in patients with satisfactory communication. This may be due to the fact that communication between the physician and the patient is fundamental to the treatment of the disease, and a breakdown in physician–patient communication not only reduces the patient's confidence in the treatment of the disease, but may also lead to catastrophic events. The study by Milzer et al. [28] showed that two-thirds of cancer patients believed that there were communication barriers between physicians and patients, such as patients' belief that doctors did not have time to discuss knowledge about the disease with patients, patients' belief that there was no cure for cancer, and physicians' lack of patience with patients. In addition, when patients are diagnosed with cancer, due to the lack of comprehensive knowledge of the disease, it is often easy to fall into a painful predicament, increasing distrust of physicians, leading to communication barriers between physicians and patients, and increasing the fear of cancer recurrence. Therefore, patients should be encouraged to express their needs in a timely manner and talk about their worries about the disease, and physicians should observe patients' emotions comprehensively, answer their questions about the disease in a timely manner, and encourage them to release their stress to reduce FCR.

Patient's family relationships

We showed that Patient's family relationships was the main influencing FCR factor in patients; The poorer the patient's family relationships, the higher the incidence of fear of cancer recurrence. Lu's et al. [29] showed the similar results on patient’s family relationships and FCR in breast cancer patients. This may be due to the fact that patients with malignant bone tumors in adolescents are treated for a longer period of time, and family members are prone to fatigue and other psychological problems that make it difficult to provide adequate care, which affects the patient's outcome, thus generating a FCR Therefore, good family relationships are an effective way to reduce FCR, and physicians should increase health education for patients and caregivers, correctly guide family members to communicate more with each other, maintain a good family atmosphere, and give more psychological support to patients,, and help patients and family members to set up confidence in overcoming the disease, so as to reduce FCR.

Family hardiness

We found that the FHI score was negatively correlated with FCR levels (P < 0.001); the high the family hardiness, the lower the FCR degree in patients. Hu et al. [30] showed the similar results on family hardiness and FCR in breast cancer patients. The reason for this may be analyzed as Family hardiness is a positive force that helps restore family stability by using core strengths when family members face stressors [31]. Families with high hardiness can provide patients with more emotional and material support, which may alleviate negative emotions and reduce FCR levels. Therefore, healthcare professionals should effectively and promptly communicate with patients and their families to help restore family resilience and reduce FCR levels.

Response modalities

The results of this study showed that different co** styles resulted in different FCR levels, with positive co** being negatively correlated with FCR levels, while the negative co** was positively correlated with FCR levels. Adopting positive co** styles decreased FCR levels in patients, while negative co** styles increased these levels, consistent with Blom et al. [32]. It was previously observed [33] that adopting an upbeat co** style increased patient confidence during disease treatments, while adopting a negative co** style increased negative emotions and aggravated FCR levels. Park et al. [34] showed that cognitive behavioral therapy based on positive thinking improved psychological distress, increased positive co**, and reduced FCR levels in patients. Kang et al. [35] in their randomized controlled aerobic running exercise trial showed that running on a treadmill three times a week for 12 weeks effectively reduced patient anxiety with respect to disease and increased positive co**, thus reducing FCR levels. Patients also improved their active co** skills via telemedicine approaches after discharge from hospital [36]. Therefore, healthcare professionals should adopt positive thought-based cognitive behavioral therapies, exercises, and telemedicine strategies to help patients reduce psychological distress and increase their confidence in combating disease and reducing FCR levels.

Study limitations

Our study had some limitations. First, this was a cross-section study that did not dynamically reflect the trajectory of FCR in adolescent malignant bone tumor patients, therefore a longitudinal study should be conducted in the future to explore FCR levels in patients at different periods. Second, as this study was only a cross-sectional study, causal association was not achieved.

Conclusions

FCR was prevalent and high in adolescents with malignant bone tumors. We observed that family resilience and co** styles in adolescents were closely related to FCR levels. Therefore, healthcare professionals can improve family resilience by hel** adolescents cope with their illness and alleviating negative emotions, thereby reducing FCR.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Choi JH, Ro JY. The 2020 who classification of tumors of bone: An updated review. Adv Anat Pathol. 2021;28(3):119–38. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAP.0000000000000293.

Saraf AJ, Fenger JM, Roberts RD. Osteosarcoma: Accelerating progress makes for a hopeful future. Front Oncol. 2018;2018(8):4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2018.00004.

Collaborators GCC. The global burden of childhood and adolescent cancer in 2017: An analysis of the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(9):1211–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30339-0.

Jie Z, Rui Y, Dan Z, Yao L. Epidemiology analysis of primary tumor of skeleton system in a third-grade hospital in Bei**g from 2008 to 2017. Chin Med Rec. 2019;20(10):62–5. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-2566.2019.10.023.

Miller KD, Fidler M, Keegan TH, Hipp HS, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for adolescents and young adults, 2020. Ca: A Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(6):443–59. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21637.

Luigjes-Huizer YL, Tauber NM, Humphris G, Kasparian NA, Lam W, Lebe IS. What is the prevalence of fear of cancer recurrence in cancer survivors and patients? A systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2022;31(6):879–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5921.

Zhang X, Sun D, Qin N, Liu M, Jiang N, Li X. Factors correlated with fear of cancer recurrence in cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Cancer Nurs. 2022;45(5):406–15. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000001020.

Schapira L, Zheng Y, Gelber SI, Poorvu P, Ruddy KJ, Tamimi RM. Trajectories of fear of cancer recurrence in young breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2022;128(2):335–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33921.

Bergerot CD, Williams SB, Klaassen Z. Fear of cancer recurrence among patients with localized prostate cancer. Cancer. 2021;127(22):4140–1. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33837.

Jung W, Park J, Jeong A, Cho JH, Jeon YJ, Shin DW. Fear of cancer recurrence and its predictors among patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Cancer Surviv. 2023;5(2):15–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01419-9.

Osann K, Wenzel L, Mckinney C, Wagner L, Cella D, Fulci G. Fear of recurrence, emotional well-being and quality of life among long-term advanced ovarian cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2023;171:151–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2023.02.015.

Anderson WJ, Doyle LA. Updates from the 2020 world health organization classification of soft tissue and bone tumours. Histopathology. 2021;78(5):644–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.14265.

Mehnert A, Herschbach P, Berg P, Henrich G, Koch U. Fear of progression in breast cancer patients--validation of the short form of the fear of progression questionnaire (Fop-Q-SF). Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 52(3):274–88. https://doi.org/10.13109/zptm.2006.52.3.274 .

Wu Q, Ye Z, Li L, Liu P. Reliability and validity of chinese version of fear of progression questionnaire-short form for cancer patients. Chin J Nurs. 2015;50(12):1515–9. https://doi.org/10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2015.12.021.

Mccubbin AIT, Ma M. Family assessment : resiliency , co** and adapatation-inventories for research and practice. Madison: University of Wisconsin System; 1996.

Liu Y, Yang J, Ye B, Shen Q, Zhu J, Chen M. Reliability and validity of the chinese version of family hardiness index. J Nurs Adimin. 2014;11(14):770–2.

** styles scale. Chin J Clin Psychol. 1998;13(02):53–4.

Yang Y, Sun H, Luo X, Li W, Yang F, Xu W, Ding K, Zhou J, Liu W, Garg S, Jackson T, Chen Y, **ang YT. Network connectivity between fear of cancer recurrence, anxiety, and depression in breast cancer patients. J Affect Disord. 2022;309:358–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.119.

Walburg V, Rueter M, Lamy S, Compaci G, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Laurent G, Despas F. Fear of cancer recurrence in non- and hodgkin lymphoma survivors during their first three years of survivorship among french patients. Psychol Health Med. 2019;24(7):781–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2019.1574354.

Gotze H, Taubenheim S, Dietz A, Lordick F, Mehnert-Theuerkauf A. Fear of cancer recurrence across the survivorship trajectory: Results from a survey of adult long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2019;28(10):2033–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5188.

Chen Y, **ong Z, Hong H, Cao L, Wang Y. A longitudinal study of fear of cancer recurrence and its influencing factors in patients with bladder cancer. J Nurs Sci. 2023;6(38):100–3. https://doi.org/10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2023.06.100.

Zheng W, Hu M, Liu Y. Social support can alleviate the fear of cancer recurrence in postoperative patients with lung carcinoma. Am J Transl Res. 2022;14(7):4804–11.

Raciborska A, Bilska K, Kozinski T, Rodriguez-Galindo C. Subsequent malignant neoplasm of bone in children and adolescent-possibility of multimodal treatment. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(2):1001–7. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29020085.

Rasmussen LA, Jensen H, Pedersen AF, Vedsted P. Fear of cancer recurrence at 2.5 years after a cancer diagnosis: a cross-sectional study in Denmark. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(11):9171–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07335-5.

Murphey MD, Kransdorf MJ. Staging and classification of primary musculoskeletal bone and soft-tissue tumors according to the 2020 who update, from the ajr special series on cancer staging. Am J Roentgenol. 2021;217(5):1038–52. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.21.25658.

Van Meurs J, Stommel W, Leget C, van de Geer J, Kuip E, Vissers K, Engels Y, Wichmann A. Oncologist responses to advanced cancer patients’ lived illness experiences and effects: an applied conversation analysis study. BMC Palliat Care. 2022;21(1):37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-00917-4.

Li B, Lin X, Chen S, Qian Z, Wu H, Liao G, Chen H, Kang Z, Peng J, Liang G. The association between fear of progression and medical co** strategies among people living with HIV: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):440. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-17969-1.

Milzer M, Wagner AS, Schmidt ME, Maatouk I, Hermann S; Cancer Registry of Baden-Württemberg; Kiermeier S, Steindorf K. Patient-physician communication about cancer-related fatigue: a survey of patient-perceived barriers. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2024 Jan 25;150(2):29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-023-05555-8 .

Lu Q, Liu Q, Fang S, Ma Y, Zhang B, Li H, Song L. Relationship between fear of progression and symptom burden, disease factors and social/family factors in patients with stage-IV breast cancer in Shandong, China. Cancer Med. 2024;13(4):e6749. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.6749.

Hu X, Wang W, Wang Y, Liu K. Fear of cancer recurrence in patients with multiple myeloma: Prevalence and predictors based on a family model analysis. Psychooncology. 2021;30(2):176–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5546.

Wen DJ, Goh E. The moderating role of trajectories of family hardiness in the relationship between trajectories of economic hardship and mental health of mothers and children. Curr Psychol. 2022;2:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03972-5.

Blom M, Guicherit OR, Hoogwegt MT. Perfectionism, intolerance of uncertainty and co** in relation to fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2023;32(4):581–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.6102.

Ji J, Zhu H, Zhao JZ, Yang YQ, Xu XT, Qian KY. Negative emotions and their management in Chinese convalescent cervical cancer patients: A qualitative study. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(9):1220748310. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060520948758.

Park S, Sato Y, Takita Y, Tamura N, Ninomiya A, Kosugi T, Sado M, Nakagawa A, Takahashi M, Hayashida T, Fujisawa D. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for psychological distress, fear of cancer recurrence, fatigue, spiritual well-being, and quality of life in patients with breast cancer-a randomized controlled. 2020.

Kang DW, Fairey AS, Boule NG, Field CJ, Wharton SA, Courneya KS. A randomized trial of the effects of exercise on anxiety, fear of cancer progression and quality of life in prostate cancer patients on active surveillance. J Urol. 2022;207(4):814–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000002334.

Wagner LI, Tooze JA, Hall DL, Levine BJ, Beaumont J, Duffecy J, Victorson D, Gradishar W, Leach J, Saphner T, Sturtz K, Smith ML, Penedo F, Mohr DC, Cella D. Targeted ehealth intervention to reduce breast cancer survivors’ fear of recurrence: results from the fortitude randomized trial. JNCI. 2021;113(11):1495–505. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djab100.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank all participants and experts for their participation and contribution to this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the General Research Project of the Zhejiang Provincial Department of Education (grant number Y202249565).The funders had no role in considering the study design or in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ye Q and Feng XQ: Study concept and design, Data collection, Data analysis, Manuscript drafts; Xue M and Yu QF: Study concept and design, Data analysis, Manuscript drafts; Ren Y and Long Y: Study concept and design, Data collection, Manuscript drafts; Yao YH and Du JL: Data collection, Manuscript drafts; Ye T: Data collection, Supervision. All authors had full access to all the data in the study, and the corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee (Approval No. I2023053).Investigators explained the purpose and significance of the survey to patients and their families before radiotherapy or surgery and other treatments on the day of admission and distributed questionnaires after informed consent was obtained.

Consent for publication

All patients provided written informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, Q., Xue, M., Yu, Qf. et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adolescent patients with malignant bone tumors: a cross-section survey. BMC Public Health 24, 1471 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18963-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18963-3