Abstract

Background

High-quality mental health services can improve outcomes for people with mental health problems and abate the burden of mental disorders. We sought to identify the challenges the country’s mental health system currently faces and the human resource situation related to psychological services and to provide recommendations on how the mental health workforce situation could be addressed in China.

Methods

This study used a cross-sectional survey design. A web-based questionnaire approach and a convenience sampling method were adopted. It was carried out from September 2020 to January 2021 in China, and we finally included 3824 participants in the analysis. Descriptive statistical analysis of the characteristics of the study sample was performed. The risk factors for competence in psychological counseling/psychotherapy were assessed using multiple linear regression analysis.

Results

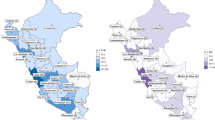

Workforce related to psychotherapy is scarce in China, especially in Western China and community mental health sectors. Psychiatrists (39.1%) and nurses (38.9%) were the main service providers of psychotherapy in psychiatric hospitals, and clinical psychologists (6.9%) and counsellors (5.0%) were seriously scarce in mental health care sectors. A total of 74.2% of respondents had no systematic psychological training, and 68.4 and 69.2% of them had no self-experience and professional supervision, respectively. Compared with clinical psychologists and counselors, psychiatrists and nurses had less training. Systematic psychological training (β = − 0.88), self-experience (β = − 0.59) and professional supervision (β = − 1.26) significantly influenced psychotherapy capacity (P<0.001).

Conclusions

Sustained effort will be required to provide a high-quality, equitably distributed psychotherapy workforce in China, despite challenges for community mental health sectors and western China being likely to continue for some time. Because mental illness is implicated in so many burgeoning social ills, addressing this shortfall could have wide-ranging benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global burden of mental disorders has risen in all countries, increasing by 13.5% between 2007 and 2017 [1, 2]. In 2016, mental disorders affected more than 1 billion people worldwide [3]. It was the leading cause of years lived with disability (YLDs), accounting for 32.4% [4]. It is projected that the estimated economic cost will increase to six trillion dollars by 2030 [5]. In China, most mental disorders have become more common in the past 30 years. The lifetime prevalence of mental disorders was 16.6% [6]. This disease burden reflects characteristics of mental disorders with high prevalence and high severity [7].

Despite the growing public health burden of mental disorders, there is still widespread neglect of the human workforce for mental health care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [8]. China, as one of the two most populous countries in the world, has improved greatly in psychiatric human resources in the context of the World Health Organization (WHO) Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan (2013–2020) and its National Mental Health Plan (2015–2020) [9]. However, the available evidence still highlights an alarming scarcity and inequitable distribution of professionals available, especially a severe lack of nonpsychiatric mental health professionals such as psychotherapists [9, 6) may also apply to other LMICs similar to the Chinese situation in psychotherapy.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, we used a cross-sectional design and a convenience sampling method. Although the sample covered three major regions of the country, the sample size in some provinces is still small, which limited our ability to find more specific characteristics of different regions and to generalize the results to similar countries. Second, quantitative research was employed in the study, and more detailed information might be missing; thus, a combination of quantitative and qualitative research is needed in the future. Third, the questionnaire in the present study was established and modified based on the WHO-AIMS [22, 33]. More structured tools and models should be applied to estimate the mental health workforce.

Conclusions

Sustained effort will be required to provide a high-quality, equitably distributed psychotherapy mental health workforce in China. Although these are very promising policies and programs, challenges for community mental health sectors and western China are likely to continue for some time. If China was able to address its unmeet mental health workforce needs, this will have substantial implications, not only for a large portion of the worldwide population but also as an inspiration for other LMICs.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- YLDs:

-

Years Lived with Disability

- LMICs:

-

Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- VIF:

-

Variance Inflation Factor

- WHO-AIMS:

-

WHO Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems

References

GBD: Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32279-7.

Patel V, Saxena S, Lund C, Thornicroft G, Baingana F, Bolton P, et al. The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet. 2018;392(10157):1553–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31612-x.

Rehm J, Shield KD. Global Burden of Disease and the Impact of Mental and Addictive Disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(2):10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-0997-0.

Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(2):171–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(15)00505-2.

Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, Finkelstein EA, Katzmarzyk PT, van Mechelen W, et al. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1311–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30383-x.

Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Liu Z, Yu X, Yan J, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(3):211–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(18)30511-x.

Furber G, Segal L, Leach M, Turnbull C, Procter N, Diamond M, et al. Preventing mental illness: closing the evidence-practice gap through workforce and services planning. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:283. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0954-5.

Sikwese A, Mwape L, Mwanza J, Kapungwe A, Kakuma R, Imasiku M, et al. Human resource challenges facing Zambia's mental health care system and possible solutions: results from a combined quantitative and qualitative study. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(6):550–7. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2010.536148.

Hu X, Rohrbaugh R, Deng Q, He Q, Munger KF, Liu Z. Expanding the Mental Health Workforce in China: Narrowing the Mental Health Service Gap. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(10):987–9. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700002.

Patel V, **ao S, Chen H, Hanna F, Jotheeswaran AT, Luo D, et al. The magnitude of and health system responses to the mental health treatment gap in adults in India and China. Lancet. 2016;388(10063):3074–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)00160-4.

de Zwaan M. Methodological aspects of controlled psychotherapy trials. Zeitschrift fur Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualitat im Gesundheitswesen. 2013;107(3):236–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zefq.2013.04.003.

Cuijpers P, Sijbrandij M, Koole SL, Andersson G, Beekman AT, Reynolds CF 3rd. The efficacy of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in treating depressive and anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of direct comparisons. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):137–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20038.

Althobaiti S, Kazantzis N, Ofori-Asenso R, Romero L, Fisher J, Mills KE, et al. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;264:286–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.12.021.

Svaldi J, Schmitz F, Baur J, Hartmann AS, Legenbauer T, Thaler C, et al. Efficacy of psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies for Bulimia nervosa. Psychol Med. 2019;49(6):898–910. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291718003525.

Huhn M, Tardy M, Spineli LM, Kissling W, Förstl H, Pitschel-Walz G, et al. Efficacy of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy for adult psychiatric disorders: a systematic overview of meta-analyses. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(6):706–15. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.112.

Cristea IA, Gentili C, Cotet CD, Palomba D, Barbui C, Cuijpers P. Efficacy of Psychotherapies for Borderline Personality Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(4):319–28. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.4287.

Mental Health Atlas 2017. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241514019.

Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):841–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61414-7.

Thornicroft G, Chatterji S, Evans-Lacko S, Gruber M, Sampson N, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al. Undertreatment of people with major depressive disorder in 21 countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210(2):119–24. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116.188078.

http://ybj.bei**g.gov.cn/zwgk/2020_zcwj/202106/P020210607655564455427.pdf. (bei**g.gov.cn) (in Chinese) 2021.

Yue JL, Liu H, Li H, Liu JJ, Hu YH, Wang J, et al. Association between ambient particulate matter and hospitalization for anxiety in China: A multicity case-crossover study. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2020;223(1):171–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2019.09.006.

Saymah D, Tait L, Michail M. An overview of the mental health system in Gaza: an assessment using the World Health Organization's Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS). Int J Ment Heal Syst. 2015;9:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-9-4.

United Kingdom Council for Psychotherapy. https://www.psychotherapy.org.uk/media/yo1i5lhs/ukcp_child_psychotherapeutic_counselling_standards_of_education_and_training_-2020.pdf.

Fu C, Wang G, Shi X, Cao F. Social support and depressive symptoms among physicians in tertiary hospitals in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):217. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03219-w.

Zoning standard of geographical areas in mainland China. https://wiki.mbalib.com/wiki/%E4%B8%89%E5%A4%A7%E7%BB%8F%E6%B5%8E%E5%B8%A6. (in Chinese).

Söderlin M, Persson G, Renvert S, Sanmartin Berglund J. Cytokines in gingival crevicular fluid in elderly rheumatoid arthritis patients in a population-based cross-sectional study: RANTES was associated with periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/jre.12887.

Cheung T, Wong S, Wong K, Law L, Ng K, Tong M, et al. Depression, Anxiety and Symptoms of Stress among Baccalaureate Nursing Students in Hong Kong: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13080779.

United Nations Economic and Social Council. Report of the Interagency and expert group on Sustainable Development Goal indicators (E/ CN.3/2016/2/Rev.1*). United Nations, New York, 2016. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/47th-session/documents/2016-2IAEG-SDGs-Rev1-E.pdf.

Psychotherapy in Italy - European Association for Psychotherapy (europsyche.org). https://www.europsyche.org/situation-of-psychotherapy-in-various-countries/italy/.

Guidance on strengthening mental health services. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s5888/201701/6a5193c6a8c544e59735389f31c971d5.shtml. (in Chinese) 2016.

Psychotherapy in Germany - European Association for Psychotherapy (europsyche.org). https://www.europsyche.org/situation-of-psychotherapy-in-various-countries/germany/.

Singla DR, Kohrt BA, Murray LK, Anand A, Chorpita BF, Patel V. Psychological Treatments for the World: Lessons from Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2017;13:149–81. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045217.

** with the completion of the study.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 82001400 and 81800482).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

**g-Li Yue and Hong-Qiang Sun developed the research question and study design. **g-Li Yue, Na Li and Jian-Yu Que oversaw the data analysis. **g-Li Yue and Na Li contributed to data interpretation and writing of the report. Jia-Hui Deng, Si-Fan Hu, Na-Na **ong, Jie Shi, and Hong-Qiang Sun revised the report. Ning Ma, Rui Chi and Si-Wei Sun managed data collection. All authors revised and approved the final report.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We declare that this study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Peking University Sixth Hospital. All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before participating in the survey.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1

. Training Situation of Participants by Different Workforces. Table S2. Training Situation of Participants by Different Hospital Levels. Table S3. Competence in Psychological Counseling/Psychotherapy by Different Workforces. Table S4. Competence in Psychological Counseling/Psychotherapy by Different Hospital Levels. Table S5. Correlations among training situations and competency.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yue, JL., Li, N., Que, JY. et al. Workforce situation of the Chinese mental health care system: results from a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 22, 562 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04204-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04204-7