Abstract

Background

Identifying practical and distinguished indicators and influencing factors of male aging may be useful in predicting subsequent aging trends, designing personalized prevention, and improving lifestyle and health.

Methods

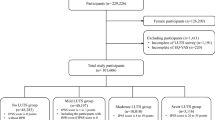

A cross-sectional, population-based study was performed in Jiashan County, China in 2016. A total of 690 local male residents, aged 40 to 80 years, were eligible for recruitment. Demographic and lifestyle information was collected through structured interviews. A self-designed head scale, the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form (SF-36), International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF5), Aging Males’ Symptoms (AMS), and International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) were used. Analysis of variance, local polynomial regression smoothing curves, multiple linear regression, and partial correlation analyses were performed.

Results

All the scales deteriorated with increasing age (P < 0.01), especially from the age of 60. The most significant changes between adjacent age groups were found in IIEF5 scores (16.7, 43.5 and 39.4%). Income, nutrition, personality and neighborhood relationship had an effect on SF-36 and AMS after adjusting for age (P < 0.01). Furthermore, neighborhood relationship modified the age effect on the head scale score and IIEF5 (P = 0.03); nutrition modified the relationship between age and SF-36 (P < 0.01).

Conclusions

Recession of reproductive health may be a distinct predictor of male aging. The associations of social inequalities or personality and health offer potential interventions for men’s health in aging. Self-reported scales may limit the precision and more physical fitness tests could be combined for a more precise assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

With an overall increase in life expectancy, quantifying the aging of different individuals has been brought into focus. The rates of biological aging are highly variable among individuals of the same chronological age. However, to date, there are no acknowledged aging markers to measure the biological age of an individual.

The epigenetic clock is thought to be the most promising molecular estimator of the biological age [1]. Some, including Horvath’s epigenetic clock, Hannum’s clock, and Levine’s clock, have been developed based on DNA methylation biomarkers for predicting aging for lifespan and healthspan [2,3,4,5]. Telomere length and epigenetic clock estimates are thought to be independent predictors of chronological age and mortality risk [6]. However, molecular biomarkers preclude their application to large-scale screens and routine physical examinations due to population specificity, invasiveness, and high costs.

In clinical settings, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) has been assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form (SF-36) questionnaire to evaluate the effect of disease or treatment [7, 8]. However, the application of SF-36 in the general population remains contradictory. An 18-year longitudinal study of civil servants (initially aged 35–55 years) based in London showed that physical health deteriorated while mental health tended to improve with age [9]. A general decline in the SF-36 score was found between 1995 and 2016 in the French population, but with wide disparities in trends between age groups [10]. A 2001–2011 US study found a declining SF-36 score in younger age groups, whereas older age groups tended to report higher mental scores [11].

The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF5), Aging Males’ Symptoms (AMS) and International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) are commonly used scales for assessing the natural degradation of reproductive health in aging males [12, 13]. IIEF5, AMS and IPSS are used to assess erectile dysfunction, symptomatic late-onset hypogonadism, and lower urinary tract symptoms, respectively. The relationship among these scales has received attention [14, 15], but the relationship between reproductive health and overall health has seldom been studied. Recently, several studies in women indicated that reproductive health was a predictor of overall health. Irregular and long menstrual cycles in adolescence and adulthood were associated with a greater risk of premature mortality (age < 70 years), and these relationships were strongest for deaths related to cardiovascular disease [16]. Young women with a low number of harvested oocytes had an increased risk of aging-related events, such as cardiovascular diseases or osteoporosis, and early ovarian aging might serve as a marker of later accelerated aging [17]. For men and women, Sexual Health and Overall Wellness (SHOW) survey showed a strong association between satisfaction with sex and overall health [18]. However, relevant studies on men in order to elaborate the relationship or the predictive effect of reproductive health on overall health are still lacking.

Apart from health degradation, aging is accompanied by changes in appearance. Facial aging is considered the most prominent and readily accessible phenotype of human aging [Full size image

The line or fold-line regressions with interaction effect and corresponding Kernel-weighted local polynomial regression smoothing curves. A Sub-figure of regression on head score and age, grou** according to neighborhood relationship. B Sub-figure of regression on SF-36 and age, grou** according to nutrition. C Sub-figure of regression on IIEF5 and age, grou** according to neighborhood relationship

Correlation analysis showed that age, head scale score, SF-36, IIEF5, AMS and IPSS displayed pairwise correlations. The highest correlation was observed between IIEF5 and age (r = 0.63). Furthermore, when age, income, nutrition, personality, and neighborhood relationship were adjusted, the absolute values of correlation coefficients (partial r) decreased, and the significance of the correlation still existed, except between head scale score and IPSS or SF-36 and IIEF5 (Table 3).