Abstract

Background

Exploring the relationship between parasitic plants and answering taxonomic questions is still challenging. The subtribe Scurrulinae (Loranthaceae), which has a wide distribution in Asia and Africa, provides an excellent example to illuminate this scenario. Using a comprehensive taxon sampling of the subtribe, this study focuses on infer the phylogenetic relationships within Scurrulinae, investigate the phylogeny and biogeography of the subtribe, and establish a phylogenetically-based classification incorporating both molecular and morphological evidence. We conducted phylogenetic, historical biogeography, and ancestral character state reconstruction analyses of Scurrulinae based on the sequences of six DNA regions from 89 individuals to represent all five tribes of the Loranthaceae and the dataset from eleven morphological characters.

Results

The results strongly support the non-monophyletic of Scurrulinae, with Phyllodesmis recognized as a separate genus from its allies Taxillus and Scurrula based on the results from molecular data and morphological character reconstruction. The mistletoe Scurrulinae originated in Asia during the Oligocene. Scurrulinae was inferred to have been widespread in Asia but did not disperse to other areas. The African species of Taxillus, T. wiensii, was confirmed to have originated in Africa from African Loranthaceae ca. 17 Ma, and evolved independently from Asian members of Taxillus.

Conclusions

This study based on comprehensive taxon sampling of the subtribe Scurrulinae, strongly supports the relationship between genera. The taxonomic treatment for Phyllodesmis was provided. The historical biogeography of mistletoe Scurrulinae was determined with origin in Asia during the Oligocene. Taxillus and Scurrula diverged during the climatic optimum in the middle Miocene. Taxillus wiensii originated in Africa from African Loranthaceae, and is an independent lineage from the Asian species of Taxillus. Diversification of Scurrulinae and the development of endemic species in Asia may have been supported by the fast-changing climate, including cooling, drying, and the progressive uplift of the high mountains in central Asia, especially during the late Pliocene and Pleistocene.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Loranthaceae is the largest mistletoe family within the order Santalales, comprising approximately 76 genera and over 1000 species. Species of the family are mainly distributed in tropical and subtropical regions of America, Africa, Asia, and Australia, with a few extending to the temperate zones in Europe and East Asia [1,2,3,4,5]. The aerial parasitic species of Loranthaceae exhibit unique morphology with a haustorium connection structure that adds to the family’s diversity worldwide. The subtribe Scurrulinae, comprising Scurrula (ca. 50 spp.) and Taxillus (ca. 35 spp.), was established by Nickrent et al. [2] and recognized by Kuijt [4], Liu et al. [5] and Su et al. [6]. Most members of Scurrulinae are distributed in Asia, except for Taxillus wiensii Polhill, the sole species in Africa [7, 8].

The subtribe Scurrulinae has received limited taxonomic attention except for the Chinese flora. Kiu [9] identified 26 Chinese species of the subtribe in Flora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicae, belonging to Scurrula and Taxillus, respectively. The genus Scurrula was divided into two sections: section Cichlanthus which includes six species and section Scurrula with five species [9]. The fruit base tapers into stalk in section Cichlanthus, while the fruit base does not form stalk in section Scurrula. The genus Taxillus was divided into three sections. The section Phyllodesmis, which includes Taxillus delavayi, T. kaempferi, and T. caloreas, is characterized by the fascicled leaves on short shoots and glabrous corolla (vs. non-fascicled leaves and hairy corolla in the other two sections). The section Lancilobi includes seven species and bears flowers with lanceolate corolla lobe, while the section Spathulilobi includes five species and the shape of corolla lobe is spathulate [9]. Kiu and Gilbert [8] recognized 28 species of Scurrulinae in Flora of China, including 10 species for Scurrula and 18 species for Taxillus. The authors suggested that Scurrula and Taxillus are generally similar in morphology such as opposite or subopposite leaves, axillary inflorescences, bisexual, 4-merous and zygomorphic flowers. Nonetheless, differences in calyx and fruit shape are important to distinguish the two genera, where Scurrula has stipitate, obovoid or clavate fruits and Taxillus has non-stipitate, ovoid or ellipsoid fruits.

The genus Phyllodesmis was established by Tieghem [10] with three species P. delavayi, P. paucifolia and P. coriacea. However, the genus was later reduced as a section of Taxillus [9] or synonym of Taxillus [8]. The molecular phylogenetic relationships of the three genera remain unclear. Therefore, it is important to test species delimitation in Taxillus and Phyllodesmis with a well-resolved phylogenetic framework based on intense taxon sampling.

Phylogenetic studies have shown that Scurrulinae is closely related to Dendrophthoinae and African Loranthaceae [3, 5, 6, 11]. The African Loranthaceae includes all the members native to continental Africa and Madagascar. Besides of the genera assigned to the subtribes Emelianthinae and Tapinanthinae sensu Nickrent et al. [2], there are also some species of Helixanthera and Taxillus distributed in Africa [4, 7]. In particular, Vidal-Russell and Nickrent [3] found that Scurrulinae was the sister group of Dendrophthoinae and African Loranthaceae, but only four members of Scurrulinae were sampled. Liu et al. [5] investigated the phylogenetic relationship and biogeography of the family Loranthaceae, which included 11 samples of Scurrulinae. This study supported that Scurrulinae including Scurrula and Taxillus formed a well-supported monophyletic group, which was estimated to originate in Asia during the early Oligocene. However, the phylogeny and classification of the subtribe were not thoroughly discussed.

The morphological characters are significant to understand generic circumscription, species delimitation, and morphological evolution [12]. Furthermore, morphological variation of some characters such as trichomes of leaf or stem, corolla lobe number and fruit shape deserve further evaluation to delimit species boundaries of Scurrulinae and related taxa. In addition, the inclusion of morphological analyses is also needed to fully unravel the relationships among the species of these two genera.

To resolve the phylogenetic position of Scurrulinae and relationships within this group, studies with a comprehensive taxon sampling to focus on the phylogenetic relationship, classification, and historical biogeography of Scurrulinae are required. The established phylogenetic framework should facilitate further collections-based integrative studies involving biogeographic and phylogenetic analyses of Scurrulinae and its close allies. Thus, the present study aims to (1) investigate the phylogenetic position of the subtribe Scurrulinae and infer the phylogenetic relationships within Scurrulinae; (2) reconstruct the biogeographical history of Scurrulinae and determine the origin of lineages within this subtribe; and (3) establish a phylogenetically-based classification incorporating both molecular and morphological evidence.

Materials and methods

Sampling, DNA extraction, and sequencing

We collected a total of 89 individuals to ensure representation of all five tribes of the Loranthaceae, with 52 of the 89 individuals belonging to the subtribe Scurrulinae. The molecular matrix was constructed using the nuclear small-subunit ribosomal DNA (SSU rDNA), large-subunit ribosomal DNA (LSU rDNA), ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and three chloroplast including rbcL, matK and trnL-F. We downloaded sequences from NCBI and generated sequences from our own collections. The voucher information and GenBank accession numbers are listed in Table S1.

We extracted Genomic DNA of all samples by using the dried leaf tissues following the CTAB procedure [13]. The primers used for PCR and sequencing in this study were referred from Vidal-Russell and Nickrent [3, 14], Wilson and Calvin [15] and Taberlet et al. [16] (Applied Biosystems, USA). We used Geneious v.8.0.5 [17] to align the sequences in this study.

Phylogenetic analyses

The two methods maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) were used to perform phylogenetic analyses of Scurrulinae. We partitioned the combined of Scurrulinae dataset into six subsets corresponding to the six DNA regions with each partition by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) as implemented in jModelTest v.2.1.6 [18], which was accessed through the CIPRES Science Gateway [19].

The ML analysis was performed in RAxML v.8.2.12 [20, 21] with the best substitution models of each partition by running 1000 bootstrap replicates. We conducted the BI in MrBayes v.3.1.2 [22] on the CIPRES Science Gateway Portal [19] applying the same substitution models as in the ML analysis. In the BI analysis, the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm was set running for 10 million generations with a total of four chains, starting from a random tree, and trees were sampled every 1000 generations. The effective sample sizes (ESSs) were checked to ensure all relevant parameters are higher than 200 by using the program Tracer v.1.6 [4, 8, 9].

Divergence time estimation

To estimate the origin and divergence times of Scurrulinae within the Loranthaceae, we used the combined datasets from nuclear (ITS, LSU rDNA and SSU rDNA) and plastid (rbcL, matK, trnLF) sequences for the dating analysis. This adjustment was made to match the markers used in previous phylogenetic studies from Santalales [3, 5, 6, 26].

The divergence time estimation of Scurrulinae was conducted by applying the uncorrelated lognormal Bayesian method in BEAST v.1.8.4 [39]. According to the models, the biogeographical events were split into range expansions and founder events, vicariance, and within-area speciation events [40].

The dispersal-vicariance analysis of Bayesian was performed in RASP v.3.2 [41, 42]. Using the trees produced by BEAST, the Bayes-DIVA approach can increase phylogenetic certainty [41, 43]. We used 10,000 trees resulting from the dating and removed 25% of the trees to obtain a condensed tree as the final representative tree with the outgroups pruned.

Biogeographic area for species within the subtribe Scurrulinae were compiled from the distribution information described in the literatures and herbarium specimens (PE, K, P, HN) for extant Scurrulinae and their relatives [5, 7,8,9]. Although the subtribe Scurrulinae is distributed in Asia and Africa, this study defined four biogeographical areas following the distribution of extant Scurrulinae and outgroup species, as well as considering the definition of biogeographical areas in Liu et al. [5]: A = Asia; B = Australasia; C = Africa (including Arabian Peninsula); D = Americas. We did not define the Indian subcontinent as a separate biogeographical area because around 136 Ma [44], the subcontinent was drifting from Australia-Antarctica earlier than the origin of the Loranthaceae and Scurrulinae.

Madagascar includes only three genera of Loranthaceae, excluding Scurrulinae. Furthermore, Liu et al. [5] suggested that Madagascan Loranthaceae originated from Africa. Madagascar was thus not recognized as a biogeographical area in this study.

Results

Phylogenetic relationship

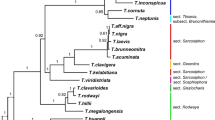

We newly generated 164 sequences belonging to 46 individuals and downloaded 213 sequences of 51 individuals in this study, resulting in a matrix of 7,778 characters. Table S2 provides detailed information on each DNA region. In comparison to the combined dataset, phylogenetic trees based on six individual DNA regions and plastid partitions revealed relationships within the Scurrulinae with poorer resolution. The phylogenetic results based on the combined dataset from ML and BI analyses were highly congruent and we thus present the Bayesian tree with BS and PP values in Fig. 1.

Majority rule consensus tree of Scurrulinae based on Bayesian inference of the combined dataset of six DNA regions (LSU rDNA, SSU rDNA, ITS, matK, rbcL and trnL-F). ML bootstrap values and posterior probabilities (PP) of the BI analysis are presented above the branches. “–” indicates the support values less than 50%. (A). Phyllodesmis delavayi; (B). Taxillus thibetensis;(C). Scurrula yunnanensis. Photo credits: C. T. Le (A, B). Liu (B, C). Abbreviations: CN: China, VN: Vietnam, ID: Indonesia; MY: Malaysia, JP: Japan, NP: Nepal

Loranthaceae was supported as monophyletic, with Nuytsia as sister to the remaining genera (Fig. 1). The three root parasitic genera were placed in a basal clade of Loranthaceae.

Subtribe Scurrulinae was supported as non-monophyletic. Three close genera Phyllodesmis, Taxillus, and Scurrula placed in three distinct subclades with strongly supported (Fig. 1). The basal subclade including only Phyllodesmis delavayi was well supported as sister to the remaining two genera Taxillus and Scurrula. The genus Taxillus was found to be closely related to Scurrula, and our results showed that Taxillus was not monophyletic with one species Taxillus wiensii nested in the African Loranthaceae. Within the Taxillus clade, T. chinensis was weakly supported as sister to the remaining members (BS = 70%, PP = 0.6) (Fig. 1), while the positions of T. limprichtii and T. nigrans were unresolved. T. kaempferi, T. caloreas, and T. levinei formed a clade with low support, and the remaining species of Taxillus formed a clade. Our results supported the monophyly of Scurrula, with S. notothixoides as sister to the remaining species (Fig. 1). Within the genus Scurrula, relationships of some species were unresolved. S. parasitica was a complex species that was not monophyletic and appeared in some clades within Scurrula. On the other hand, Taxillus wiensii from Africa is placed within African Loranthaceae.

Ancestral character state reconstruction

We explored the state evolution of eleven morphological characters in Scurrulinae using the combined phylogeny. Our results showed that “trichomes present” on young stems were the ancestral state in the subtribe, and “glabrous” was the derived state (character 1, Fig. 2A). Similarly, “trichomes present” leaves and corollas were the ancestral states, and “glabrous” was the derived state in the subtribe (characters 3 and 5, Fig. 2B, D). The ancestral state of leaf placement was “opposite or subopposite”, and “alternate” leaf was the derived state (character 2, Fig. 2C). Our analysis revealed that “ovate” was the ancestral state of bract shape and “triangular, narrow boat-shaped, and broad-triangular” were the derived character states (character 8, Fig. 3B). While the ancestral state of inflorescence type was unstable for the whole subtribe, our result indicated that inflorescence of Taxillus’s ancestor was umbel (character 4, Fig. 3A). Similarly, the ancestral state of corolla lobe number of the subtribe was unstable (character 6, Fig. 3C). Our results showed that ancestor of Taxillus, Scurrula, and Phyllodesmis had 4-merous flowers (Fig. 3C). For the character 7, “flower pedicel present” was the ancestral state, and “flower pedicel absent” was the derived state (Fig. 3D), and the latter was only seen in Taxillus wiensii. The ancestral state of bract length (character 9) was not resolved, however, our results showed that “bract length shorter than 2 mm” was the ancestral state of Taxillus and Scurrula (Fig. 4A). Stigma “capitate to subcapitate” was the ancestral state, while “globose to subglobose” was derived (character 10, Fig. 4B). Meanwhile, fruit shape “ellipsoid or ovoid or subglobose” was found as the ancestral state, and “pyriform or clavate” and “cylindric” were derived in the subtribe (character 11, Fig. 4C).

Divergence times estimation

The divergence time estimations for the Loranthaceae and subtribe Scurrulinae are shown in Fig. 5. The crown age of the family Loranthaceae was estimated to be approximately 62.77 Ma (95% HPD: 53.22–75.46 Ma; node 1, Fig. 5). The tribe Lorantheae initially diverged around 42.34 Ma (95% HPD: 41.15–45.73 Ma; node 2, Fig. 5).

Maximum clade credibility tree inferred from BEAST based on the combined datasets of six DNA regions. The bars around node ages indicate 95% highest posterior density intervals. Node constraints are indicated with stars. Nodes of interests were marked as 1–6. Abbreviations: CN: China, VN: Vietnam, ID: Indonesia; MY: Malaysia, JP: Japan, NP: Nepal

The subtribe Scurrulinae split from the ancestors of the subtribe Dendrophthoinae plus African Loranthaceae at 32.37 Ma (95% HPD: 26.82–37.59 Ma; node 3, Fig. 5). Within Scurrulinae, Phyllodesmis diverged from the remaining taxa of the subtribe at 25.46 Ma (95% HPD: 19.54–31.58 Ma; node 4, Fig. 5). The two genera Scurrula and Taxillus split from each other at 21.23 Ma (95% HPD: 15.77–27.27 Ma; node 6, Fig. 5), then started to diversify at 16.73 Ma (95% HPD: 11.33–22.73 Ma; node 7, Figs. 5) and 16.30 Ma (95% HPD: 10.70–22.39 Ma; node 8, Fig. 5), respectively. Additionally, Taxillus wiensii separated with Oedina pendens at 17.78 Ma (95% HPD: 8.84–25.98 Ma; node 5, Fig. 5).

Ancestral range reconstruction

Results of ancestral range reconstruction analyses from BioGeoBEARS and Bayes-DIVA are congruent. Among the six models used in our BioGeoBEARS analysis, models including three parameters had higher log likelihood values than models including two parameters (Table 2), this result shows that jump speciation such as dispersal between non-adjacent areas is an important pattern in range variation of the Loranthaceae. Moreover, the results from BioGeoBEARS analyses indicated that DEC + j is the best-fit biogeographic model for ancestral range reconstruction of Loranthaceae. Therefore, we are only presenting the reconstruction from BioGeoBEARS using the DEC + j model (Fig. 6). Additionally, the result from Bayes-DIVA is exhibit in Fig. S1. Node numbers in Figs. 5 and 6 are consistent, and we summarize the divergence time estimations and ancestral range reconstruction in Table 3. Biogeographic stochastic map** (BSM) under the DEC + j model indicated that most biogeographic events comprised within-area speciation (78%) and dispersals (20.7%), with very few (1.3%) vicariant events (Table S4). The stem group of Scurrulinae was estimated to originate from Asia (area A) (node 3, Fig. 6), and Scurrulinae subsequently diversified in Asia during the Oligocene. The genus Phyllodesmis was estimated to originate in Asia during the Late Oligocene (node 4, Fig. 6). Taxillus and Scurulla also originated in Asia and diversified during the middle Miocene (nodes 7 and 8, Fig. 6). Additionally, the only African member of Scurullinae (Taxillus wiensii) was estimated to diverge from its African relative during the Miocene (nodes 5, Fig. 6).

Ancestral range reconstruction of Scurrulinae by BioGeoBEARS (j = 0.0169, LnL = − 48.35). Geologic time scale is shown at the bottom. Numbers outside nodes correspond to the node numbers in Fig. 5. Area abbreviations are as follows: A = Asia; B = Australasia; C = Africa (including Arabian Peninsula); D = Americas. Abbreviations: CN: China, VN: Vietnam, ID: Indonesia; MY: Malaysia, JP: Japan, NP: Nepal

Discussion

Phylogenetic relationship

With extensive taxon and gene sampling, this study retrieves a well-supported topology for most clades, although some subclades within the genera Taxillus and Scurrula exhibit weak support (Fig. 1). Our results demonstrate that the subtribe Scurrulinae is non-monophyletic, with one species, Taxillus wiensii, nested within the African Loranthaceae clade. Phyllodesmis is strongly supported as sister to the two genera, Taxillus and Scurrula. Morphological characters are useful to support relationships within the subtribe, particularly the glabrous young stems and leaves can distinguish Phyllodesmis from Taxillus and Scurrula (Fig. 2A, B). Taxillus wiensii clade is characterized by bract shape, corolla lobe number, flower pedicel (Fig. 3B, C, D), while, the clade of Taxillus and Scurrula is characterized by bract length (Fig. 4A). Our character optimizations suggest that the two genera Taxillus and Scurrula are very similar in morphology, and they share ancestral morphological states of most characters. However, they have evolved differently in the shape of fruit and stigma (Fig. 4B, C). Based on our observation of specimens and fresh plants in the field, fruits of Scurrula are always pyriform or clavate sometimes, while those of Taxillus are usually ellipsoid, ovoid, or cylindrical.

Scurrula comprises around 50 species in China and Southeast Asia. Our phylogenetic analysis revealed unexpected relationships between the S. parasitica complex and the S. chingii complex (Fig. 1). S. parasitica was found to be a complex member in this study based on molecular data. There are two varieties of S. parasitica: S. parasitica var. parasitica and S. parasitica var. graciliflora. Our results demonstrated that the different individuals of S. parasitica var. parasitica and S. parasitica var. graciliflora did not form a monophyletic clade (Fig. 1). Moreover, S. parasitica var. graciliflora can be easily distinguished from S. parasitica var. parasitica by its greenish-yellow corolla (versus red corolla in S. parasitica var. parasitica). Based on our findings, we suggest that S. parasitica var. graciliflora should be redefined as a separate species. A detailed treatment of this taxon will be provided in a future study.

Scurrula chingii is composed of two varieties: S. chingii var. yunnanensis and S. chingii var. chingii [8]. Both varieties are non-monophyletic by Liu et al. [5] and our study (Fig. 1). Although the position of S. chingii var. yunnanensis is uncertain in our phylogenetic tree, it is distant from S. chingii var. chingii as reported by Liu et al. [5]. Furthermore, S. chingii var. yunnanensis can be easily distinguished from S. chingii var. chingii based on several characteristics, including glabrous leaf blade surfaces (versus rusty red tomentose or glabrous abaxial surface in S. chingii var. chingii), shorter peduncle and floral axis less than 10 mm (vs. 10–25 mm in S. chingii var. chingii), and lanceolate corolla lobes (versus subspatulate lobes in S. chingii var. chingii). Additionally, Scurrula chingii var. yunnanensis is endemic to Yunnan (China), while S. chingii var. chingii is distributed in Guangxi, southern Yunnan (China), and northern Vietnam. Based on our results, S. chingii var. yunnanensis should be redefined to the species rank. The detail treatment will be provided in a future study.

Taxillus includes approximately 35 species from tropical Asia (India and Sri Lanka to China, Japan, Philippines, Borneo) and Africa (Kenya coast). Taxillus is generally characterized by low host specificity. Taxillus chinensis (DC.) Danser, a Malesian species, is widely distributed in west of Charles’s Line. On the other hand, T. wiensii Polhill, the only species of Taxillus in East Africa, has a narrow distribution limited to the Kenya coast.

Polhill and Wiens [7] suggested that although the morphology of T. wiensii is similar to the species of Taxillus in Sri Lanka, the flowers of T. wiensii appear different from the Asiatic species due to the erect and possibly spontaneously open corolla-lobes. Additionally, Polhill and Wiens [7] proposed that T. wiensii is more comparable to the African genera that have been segregated from sections of Taxillus based on flower characteristics, such as sect. Bakerella (Tieghem) Balle, sect. Remoti, and sect. Septulina. Furthermore, all species of Loranthaceae in continental Africa and Madagascar, except Socratina and one species of Septulina, can be distinguished by their flowers that open spontaneously with erect or spreading corolla-lobes, rather than explosively as in Taxillus. Bakerella is entirely glabrous, while Socratina has trichomes, with a unique occurrence of fine indumentum on the inner face of the corolla-lobes. In terms of morphology, T. wiensii can be distinguished from the Asian Taxillus by its 5-merous (rather than 4 merous) flowers and bract shape (as shown in Fig. 3C). Our analyses of character optimizations indicate that T. wiensii and the Asian Taxillus have evolved differently in terms of flower and bract structure. It is difficult to improve the generic classification without detailed consideration of relationship between T. wiensii and the Asian Taxillus species [7]. Our molecular results indicate that T. wiensii is placed within African Loranthaceae and is clearly different from the Asian Taxillus (Fig. 1). Therefore, we suggest that the African Taxillus should be recognized as a new genus, and the detail description will be provided in a future study.

Furthermore, our molecular analyses revealed that Taxillus limprichtii and its variety T. limprichtii var. longiflorus (Lecomte) H. S. Kiu do not form a monophyletic group. Therefore, we recommend that their taxonomic classification be re-evaluated in future studies.

Phyllodesmis, comprised four species, was initially described by Tieghem [11]. However, subsequent research reduced this genus to a synonym of Taxillus, incorporating T. delavayi (Tieghem) Danser, T. kaempferi (Candolle) Danser, T. caloreas (Diels) Danser, and T. renii H.S. Kiu [8]. Our results support Phyllodesmis as a distinct clade from Taxillus and Scurrula with strong support (Fig. 1). Moreover, the Phyllodesmis clade includes only P. delavayi, a species that does not parasitize species of Pinaceae, unlike the remaining three species. Furthermore, Phyllodesmis can be easily distinguished from all other Taxillus members based on characteristics of leaves alternate (as opposed to opposite or subopposite), glabrous young branchlets (trichomes not present) and both surfaces of leaves (Fig. 7). Thus, we suggest reinstating Phyllodesmis as a recognized genus, comprising only one species, P. delavayi.

Taxonomic treatment of Phyllodesmis

Phyllodesmis Tiegh. in Bull. Soc. Bot. France 42: 255. 1895 (Fig. 7).

Aerial parasite, small shrubs, glabrous. Leaves alternate, sometimes subopposite, pinnately veined. Inflorescences at leafless node, umbels 2–4-flowered; 1 bract subtending each flower, usually scale-like. Flowers bisexual, 4-merous, zygomorphic. Calyx ellipsoid or ovoid, rarely subglobose, base rounded, limb annular, entire or denticulate, persistent. Mature flower bud tubular, tip ellipsoid. Corolla sympetalous, slightly curved, basal portion ± inflated, split along 1 side at anthesis, lobes all reflexed toward the side away from the split, red, glabrous. Stamens inserted at base of corolla lobes; filaments short; anthers 4-loculed. Pollen grain trilobate or semilobate in polar view. Ovary 1-loculed; placentation basal. Style filiform, 4-angled; stigma usually capitate. Berry ellipsoid or ovoid, exocarp leathery, verrucose or granular, rarely smooth, pubescent or glabrous, base rounded.

Phyllodesmis delavayi Tieghem, Bull. Soc. Bot. France 42: 255. 1895. Taxillus delavayi (Tieghem) Danser, Verh. Kon. Ned. Akad. Wetensch., Afd. Natuurk., 29(6): 123. 1933. Type: China, Yunnan, Dali, Feb. 1887, Delavay 2620 (P, syntypes barcodes P00756268!, P00756269!, P00756270!, P00756271!)

Morphology

—Aerial parasite, small shrubs 0.5–1 m tall, glabrous. Branches grayish, brown to almost blackish, usually lenticellate, glabrous when young, later often longitudinally fissured. Leaves simple, alternate, sometimes sub-opposite; petiole sub-sessile, 3–5 mm long; leaf blade elliptic to lanceolate, 3–6 × 1.3–2.5 cm, leathery, glabrous on both surfaces, lateral veins 3–4 pairs, adaxially somewhat obscure, base cuneate, slightly decurrent, apex obtuse, margin entire, or slightly undulate, brown, young leaves brown to reddish, adaxially glossy, green, abaxially pale green. Inflorescence with 1–2 umbels, spreading along leafless branches, rarely at leaf base, 2-7-flowered; peduncle almost sessile, ca. 1–2 mm, bracteates; bracts ovate, ca. 2 mm long, glabrous. Pedicel terete, 5–15 mm long, pale green, glabrous. Calyx ellipsoid, ca. 2.5 mm long, limb annular, entire or minutely 4-toothed. Mature bud 4–5 cm, tip ellipsoid, tip inside yellow. Corolla red, slightly curved, glabrous, lobes linear-lanceolate, 6–9 mm long, reflexed, abaxially yellow. Filaments red, short ca. 2.5 mm long; anthers orange, ca. 1.5 mm long. Ovary 1-loculed. Style red, ca. 3–5 cm long. Stigma red, capitates. Berry yellow or orange, ellipsoid, 8–10 × 3–4 mm, glabrous.

Phenology

—Flowering in Feb–May, fruiting in Apr–Sep.

Habitat

—Forests, mountain slopes; 1500–3000 m.

Conservation

—While not threatened as a species, and not listed under IUCN criteria, some populations of Phyllodesmis do require protection from over collection for medicinal use.

Distribution

—China: Yunnan, Guangxi, Sichuan, **zang; Myanmar, and Vietnam: Lao Cai, Lai Chau.

Selected specimens examined

—VIETNAM: Lao Cai: Sapa district, San Sa Ho commune, Cat Cat village, October 2019, Van Du Nguyen, Hung Manh Nguyen, Xuan Thanh Trinh and Chi Toan Le DMTT38, DMTT39 (HN). CHINA: Sichuan: Dêrong County, Zigen, Jul 1981, Qinghai-Tibetan Expedition Team 1734 (PE); Shimian County, 1955, C.J. **e 39,892 (PE). **zang: Zayü County, Shangchayu, Jul 1980, C.C. Ni et al. 740 (PE). Yunnan: Wenshan County, Mt. Laojun, April 1993, Y.M. Shui 1904 (PE); Dêqên County, Benzilan, July 1981, Qinghai-Tibetan Expedition Team 1864 (PE).

Historical biogeography of Scurrulinae

Asian origin of Scurrulinae

Our divergence time estimations for Scurrulinae are consistent with those from Grímsson et al. [26] and Liu et al. [5], and the stem age of Loranthaceae in our study is close to the results of Magallón et al. [45] and Liu et al. [5] (Table S5). The biogeographic analyses and divergence time estimations suggest that the stem group of Scurrulinae originated in Asia ca. 32.37 Ma during the Oligocene (node 3, Figs. 5 and 6; Table 3), with a crown age dating back to 25.46 Ma (95% HPD: 19.54–31.58 Ma; node 4, Figs. 5 and 6; Table 3). The Indian subcontinent began drifting from Australia-Antarctica ca. 136 Ma [44], and connected to mainland Asia ca. 44 Ma. Thus, the connection between India and Asia occurred much earlier than the origin of the Scurrulinae. According to Li et al. [46], the uplift of high mountains in Asia during the Oligocene-Miocene, combined with the southwest monsoon in Asia, probably provided ideal conditions for colonization and wide distribution of Scurrulinae. Additionally, short-distance dispersal in Asia is also important for domination or wide distribution of plants. **ang et al. [47] suggested that the presence of tropical forests with key plant families such as Fabaceae, Fagaceae, and Rubiaceae is an important factor supporting the origin and divergence of the epiphytic plant genus Dendrobium (Orchidaceae) in Asia, this is consistent with the situations of aerial parasitic plants Scurrulinae or understory vegetation such as Alpinia (Zingiberaceae) [48] and Menispermaceae [49]. Therefore, Asian Scurrulinae, including Indian Scurrulinae, likely originated in Asia and may have spread throughout the area by birds or small animals [50,51,52].

The Asian Loranthaceae migrated from Australia in the late Eocene (Fig. 6). Notably, despite several species of Scurrulinae being found in Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines [4, 8, 9], which are geographically close to Australasia, there is no evidence of Scurrulinae dispersing from Asia to Australasia. While several Loranthaceae genera are common to both regions, including Lepeostegeres, Amylotheca, Decaisnina, Macrosolen, and Cecarria [2, 7], and our study suggests that all migration events from Asia to Australasia occurred before about 35 Ma, which is earlier than the origin of Scurrulinae. Thus, the Phyllodesmis, Taxillus and Scurrula of Scurrulinae may be endemic genera to Asia.

Liu et al. [5] proposed that within-area speciation events are more prevalent in most of the large clades that are endemic to single areas of Loranthaceae. They suggested that dispersal without “range contractions” was the main driver of range evolution, occurring more frequently than vicariance events. Our BSM results (Table S4) are support that within-area speciation events are the main factor in creating the Asian endemic group of Scurrulinae. Dispersal events have been considered as the most common factor for worldwide distributed plants, including Loranthaceae and Scurrulinae lineages [40]. Our BSM indicates that the dispersal events of Scurrulinae occurred without “range contractions” or “founder events”, which is consistent with biogeographic history of the subtribe Scurrulinae (Table S4). After originating in Asia, Scurrulinae did not disperse to other regions. African Loranthaceae evolved from Asian ancestor and Taxillus wiensii originated in Africa from the African Loranthaceae ancestor. Short-distance dispersal events between proximal regions appear to have been frequent in the historical biogeography of Scurrulinae, and it may have been facilitated by the colonization or domination of Scurrulinae host plants in tropical forests.

Species of Loranthaceae are distributed worldwide [2, 4, 5, 8]. However, due to geographic distance and climate change, they are becoming endemic groups for each continent, resulting in fewer shared genera [5]. Our results suggest that Scurrulinae originated and diverged in Asia during a period when rainforests dominated the continent [48, 53] (Fig. 6). The members of this subtribe evolved and adapted to the living conditions in Asia, and the rapid climate changes, cooling, drying, and the progressive uplift of the high mountains in central Asia, especially during the late Pliocene and Pleistocene, might have promoted the diversification of Scurrulinae and prevented their dispersal to other continents [54]. Our study does not recognize any migration of Scurrulinae to other continents since the early Oligocene, except for one species of Taxillus that originated in Africa.

African origin and diversification of Taxillus Wiensii

The present study supports the placement of Taxillus wiensii within Africa Loranthaceae and its close relationship to Tapinanthus constrictiflorus (Figs. 1 and 6). Biogeographic analyses indicate that Taxillus wiensii originated and diversified in Africa (Fig. 6), and this species is likely not a part of Scurrulinae. Taxillus wiensii was considered as the only member of Taxillus in Africa, with dispersal from Asia to Africa proposed to explain its historical biogeography [3, 7]. However, this study confirms that the ancestor of Taxillus wiensii is African Loranthaceae, and this species likely evolved separately from Taxillus in Asia ca. 17 Ma (Figs. 5 and 6). A similar situation was encountered in the genus Helixanthera, with Liu et al. [5] demonstrating differences between African and Asian Helixanthera and suggesting that African Helixanthera may be recognized as a distinct genus in the future studies.

Conclusion

Based on comprehensive taxon sampling of the subtribe Scurrulinae, this study strongly supports the relationship among genera of the subtribe. Phyllodesmis is recognized as a separate genus from its allies Taxillus and Scurrula while African Taxillus may be treated as a new genus from Africa in the future studies. The mistletoe Scurrulinae originated in Asia during the Oligocene, and then was widespread in Asia and did not disperse to other areas. Taxillus and Scurrula diverged during the climatic optimum in the middle Miocene. African Taxillus originated in Africa from African Loranthaceae approximately 17 Ma, clearly different from Taxillus in Asia. Diversification of Scurrulinae and the development of endemic species in Asia may have been promoted by the fast-changing climate, including cooling, drying, and the progressive uplift of the high mountains in central Asia, especially during the late Pliocene and Pleistocene.

Data availability

All the sequences generated in this study are deposited in the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 19 December 2023), under the following accession number: OR964417-OR964480, OR976247-OR976261, OR987685-OR987719, and PP002640-PP002689. Other data used in this study can be found at the Science Data Bank (https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.18240).

References

Nickrent DL. The parasitic plant connection. 2017. http://parasiticplants.siu.edu/. Last accessed September 6, 2017.

Nickrent DL, Malécot V, Vidal-Russell R, Der JP. A revised classification of Santalales. Taxon. 2010;59:538–58.

Vidal-Russell R, Nickrent DL. Evolutionary relationship in the showy mistletoe family (Loranthaceae). Am J Bot. 2008a;95:1015–29.

Kuijt J. Santalales. In: Kubitzki K, editor. The families and genera of vascular plants, flowering plants: eudicots; Santalales, Balanophorales. Volume 12. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2015. pp. 2–189.

Liu B, Le CT, Barrett RL, Nickrent DL, Chen ZD, Lu LM, Vidal-Russell R. Historical biogeography of Loranthaceae (Santalales): diversification agrees with emergence of tropical forests and radiation of songbirds. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2018;124:199–212.

Su HJ, Hu JM, Anderson FE, Der JP, Nickrent DL. Phylogenetic relationships of Santalales with insights into the origins of holoparasitic Balanophoraceae. Taxon. 2015;64:491–506.

Polhill R, Wiens D. Mistletoes of Africa. Richmond-Surrey, UK: The Royal Botanic Gardens Kew; 1998.

Kiu HS, Gilbert MG. Loranthaceae. In: Wu ZY, Raven PH, Hong DY, editors. Flora of China. Volume 5. Bei**g, China: Science; St. Louis, USA: Missouri Botanical Garden Press;; 2003. pp. 220–39.

Kiu HS. Loranthaceae. In: Kiu HS, Ling YR, editors. Flora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicae. Volume 24. Science, Bei**g;; 1988. pp. 86–158. [In Chinese.].

Tieghem PV. Taxillus. Bull Bot Soc France. 1895;42: 255.

Vidal-Russell R, Nickrent DL. The biogeographic history of Loranthaceae. Darwiniana. 2007;45:34–54.

Parmar G, Dang VC, RabarijaonaRN, Chen ZD, Jackes BR, Barrett RL, Zhang ZZ, Niu YT, Trias-Blasi A, Wen J, Lu LM. Phylogeny, character evolution and taxonomic revision of Causonis, a segregate genus from Cayratia (Vitaceae). Taxon. 2021; 70: 1188–1218.

Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Lett. 1987;19:11–5.

Vidal-Russell R, Nickrent DL. The first mistletoes, origins of aerial parasitism in Santalales. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008b;47:523–37.

Wilson CA, Calvin CL. An origin of aerial branch parasitism in the mistletoe family, Loranthaceae. Am J Bot. 2006;93:787–96.

Taberlet P, Gielly L, Pautou G, Bouvet J. Universal primers for amplification of three non-coding regions of chloroplast DNA. Plant Mol Biol. 1991;17:1105–9.

Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, Drummond A. Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–9.

Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. JModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and high-performance computing. Nat Methods. 2012;9:772.

Miller MA, Pfeiffer W, Schwartz T. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. In: Proceedings of the Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE). Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), New Orleans, USA, 2010; 1–8.

Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC, maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–90.

Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst Biol. 2008;57:758–71.

Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–4.

Rambaut A, Suchard MA, **e D, Drummond AJ. Tracer v1.6. 2014. http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/.

Su HJ, Liang SL, Nickrent DL. Plastome variation and phylogeny of Taxillus (Loranthaceae). PLoS ONE. 2021;16(8):e0256345.

Maddison WP, Maddison DR. Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. 2019. Version 3.61. http://www.mesquiteproject.org.

Grímsson F, Kapli P, Hofmann CC, Zetter R, Grimm GW. Eocene Loranthaceae pollen pushes back divergence ages for major splits in the family. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3373.

Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, **e D, Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1969–73.

Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. TreeAnnotator. Version 1.8, distributed as part of the BEAST Package. 2010. http://beast.community/installing.

Rambaut A. FigTree v.1.4. 2009. http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/.

Zamaloa MDC, Fernández CA. Pollen morphology and fossil record of the feathery mistletoe family Misodendraceae. Grana. 2016;55:278–85.

Macphail M, Jordan G, Hopf F, Colhoun E. When did the mistletoe family Loranthaceae become extinct in Tasmania? Review and conjecture. In: Haberle SG, David B, editors. Peopled landscapes (Terra Australis 34) archaeological and biogeographic approaches to landscapes. Canberra: Australian National University; 2012. pp. 255–70.

Mildenhall DC. New Zealand late cretaceous and cenozoic plant biogeography: a contribution. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 1980;31:197–233.

Matzke NJ. Probabilistic historical biogeography: new models for founderevent speciation, imperfect detection, and fossils allow improved accuracy and model-testing. Front Biogeogr. 2013;5:242–8.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing. Austria: Vienna; 2016.

Ree RH, Smith SA. Maximum likelihood inference of geographic range evolution by dispersal, local extinction, and cladogenesis. Syst Biol. 2008;57:4–14.

Ronquist F. Dispersal-vicariance analysis: a new approach to the quantification of historical biogeography. Syst Biol. 1997;46:195–203.

Landis MJ, Matzke NJ, Moore BR, Huelsenbeck JP. Bayesian analysis of biogeography when the number of areas is large. Syst Biol. 2013;62:789–804.

Lian L, **ang KL, Ortiz RDC, Wang W. A multi-locus phylogeny for the Neotropical Anomospermeae (Menispermaceae): implications for taxonomy and biogeography. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2019;136:44–52.

Matzke NJ. Stochastic map** under biogeographical models. 2015. http://phylo.wikidot.com/biogeobears#stochastic_map** (accessed 1 June 2015).

Dupin J, Matzke NJ, Särkinen T, Knapp S, Olmstead RG, Bohs L, Smith SD. Bayesian estimation of the global biogeographical history of the Solanaceae. J Biogeogr. 2017;44:887–99.

Yu Y, Harris AJ, He X. RASP (Reconstruct Ancestral State in Phylogenies) 2.0 Beta. 2011. http://mnh.scu.edu.cn/soft/blog/RASP.

Yu Y, Harris AJ, Blair C, He X. RASP (reconstruct ancestral state in Phylogenies): a tool for historical biogeography. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2015;87:46–9.

Nylander JA, Olsson U, Alstrom P, Sanmartin I. Accounting for phylogenetic uncertainty in biogeography: a bayesian approach to dispersal vicariance analysis of the thrushes (Aves: Turdus). Syst Biol. 2008;57:257–68.

Gibbons AD, Whittaker JM, Müller RD. The breakup of East Gondwana: assimilating constraints from cretaceous ocean basins around India into a best-fit tectonic model. J Geophys Res. 2013;118:808–22.

Magallón S, Gómez-Acevedo S, Sánchez-Reyes LL, Hernández-Hernández T. A metacalibrated time-tree documents the early rise of flowering plant phylogenetic diversity. New Phytol. 2015;207:437–53.

Li M, Tetsuo OT, Gao YD, Xu B, Zhu ZM, Ju WB, Gao XF. Molecular phylogenetics and historical biogeography of Sorbus Sensu Stricto (Rosaceae). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2017;111:76–86.

**ang XG, Mi XC, Zhou HL, Li JW, Chung SW, Li DZ, Huang WC, ** WT, Li ZY, Huang LQ, ** XH. Biogeographical diversification of mainland Asian Dendrobium (Orchidaceae) and its implications for the historical dynamics of evergreen broad-leaved forests. J Biogeogr. 2016;43:1310–23.

Le CT, Do TB, Pham TMA, Nguyen VD, Nguyen SK, Nguyen VH, Cao PB, Omollo WO. Reconstruction of the evolutionary biogeography reveals the origins of Alpinia Roxb. (Zingiberaceae): a case of out-of-Asia migration to the Southern Hemisphere. Acta Bot Bras. 2022;36:e2021abb0255.

Wang W, Ortiz RDC, Jacques FMB, **ang XG, Li HL, Lin L, Li RQ, Liu Y, Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Chen ZD. Menispermaceae and the diversification of tropical rainforests near the cretaceous–paleogene boundary. New Phytol. 2012;195:470–8.

Amico G, Aizen MA. Mistletoe seed dispersal by a marsupial. Nature. 2000;408:929–30.

Klicka J, Voelker G, Spellman GM. A molecular phylogenetic analysis of the true thrushes (Aves: Turdinae). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2005;34:486–500.

Cibois A, Thibault JC, Bonillo C, Filard CE, Watling D, Pasquet E. Phylogeny and biogeography of the fruit doves (Aves: Columbidae). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2013;70:442–53.

Weeks A, Daly DC, Simpson BB. The phylogenetic history and biogeography of the frankincense and myrrh family (Burseraceae) based on nuclear and chloroplast sequence data. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2005;35:85–101.

Lin L, Tang L, Bai YJ, Tang ZY, Wang W, Chen ZD. Range expansion and habitat shift triggered elevated diversification of the rice genus (Oryza, Poaceae) during the Pleistocene. BMC Evol Biol. 2015;15:182.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research is funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31970212 and 31800178), the National Key Research Development Program of China (2022YFF0802300, 2022YFC2601200), the International Partnership Program (151853KYSB20190027) and Biological Resources Program (KFJ-BRP-017-087) of CAS, Sino-Africa Joint Research Centre, Chinese Academy of Sciences, CAS International Research and Education Development Program (SAJC202101), and Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development (NAFOSTED) under grant No. 106.03-2019.12.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BL and CTL conceived and designed the experiment. CTL and WOO performed the experiments. LML, ZDC, VDN and CTL assisted in data analysis. CTL and BL wrote the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were in accordance with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation. The specimens collected in the field have obtained the permission of institutions and governments, which meet the requirements of legal research, and have been identified and deposited in the herbaria (the detailed voucher information of the specimens together with the name of collectors and herbarium codes are given in Supplementary Table S1).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Le, C.T., Lu, L., Nguyen, V.D. et al. Phylogeny, character evolution and historical biogeography of Scurrulinae (Loranthaceae): new insights into the circumscription of the genus Taxillus. BMC Plant Biol 24, 440 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-024-05126-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-024-05126-0