Abstract

Many citizens across the liberal democratic world are highly critical of their elected representatives’ conduct. Drawing on original survey data from Britain, France and Germany, this paper offers a unique insight into prevailing attitudes across Europe’s three largest democracies. It finds remarkable consistencies in the ethical priorities of British, French and German citizens: although there is some individual-level variation, respondents in all three countries overwhelmingly prioritise having honest representatives. It also finds differences in the types of behaviour that cause most concern in each country. The paper then examines how individuals’ preferences shape their concerns about prevailing standards. The findings are consistent with the idea that citizens’ predispositions have an ‘anchoring’ effect on perceptions of political integrity. Finally, the paper considers whether established democracies are susceptible to an ‘expectations gap’ between citizens’ expectations of conduct and what ‘normal’ politics can realistically deliver.

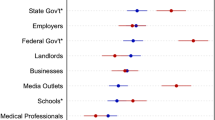

Note: ‘Don’t knows’ are excluded.

Note: ‘Don’t knows’ are excluded.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Allen, N. and Birch, S. (2011) Political conduct and misconduct: Probing public opinion. Parliamentary Affairs 64(1): 61–81.

Allen, N. and Birch, S. (2012) On either side of a moat? Elite and mass attitudes towards right and wrong. European Journal of Political Research 51(1): 89–116.

Allen, N. and Birch, S. (2015) Ethics and Integrity in British Politics: How Citizens Judge their Politicians’ Conduct and Why It Matters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Anderson, C.J. and Tverdova, Y.V. (2003) Corruption, political allegiances, and attitudes toward government in contemporary democracies. American Journal of Political Science 47(1): 91–109.

Atkinson, M.M. and Bierling, G. (2005) Politicians, the public and political ethics: Worlds apart. Canadian Journal of Political Science 38(4): 1003–1028.

Baldini, G. (2015) Is Britain facing a crisis of democracy? Political Quarterly 86(4): 540–549.

Becquart-Leclercq, J. (1989) Paradoxes of political corruption: A French view. In: A. Heidenheimer, M. Johnston and V. LeVine (eds.) Political Corruption: A Handbook. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, pp. 191–210.

Besley, T. (2005) Political selection. Journal of Economic Perspectives 19(3): 43–60.

Birch, S. (2010) Perceptions of electoral fairness and voter turnout. Comparative Political Studies 43(12): 1601–1622.

Birch, S. and Allen, N. (2012) “There will be burning and a-looting tonight”: The social and political correlates of law-breaking. The Political Quarterly 83(1): 33–43.

Bowler, S. and Karp, J. (2004) Politicians, scandals, and trust in government. Political Behavior 26(3): 271–287.

Committee on Standards in Public Life (2011) Survey of Public Attitudes Towards Conduct in Public Life 2010. London: Committee on Standards in Public Life.

Converse, P.E. (1995) Foreword. In: R.E. Petty and J.A. Krosnick (eds.) Attitude Strength: Antecedents and Consequences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 11–16.

Corbett, J. (2015) Diagnosing the problem of anti-politicians: A review and an agenda. Political Studies Review. doi:10.1111/1478-9302.12076.

Corbett, J. (2016) Democratic gaps, traps and tricks. Comment on: Flinders, M. (2015) The problem with democracy. Parliamentary Affairs 69(1): 204–206.

Curtice, J. and Heath, O. (2012) Does choice deliver? Public satisfaction with the health service. Political Studies 60(3): 484–503.

Davis, C.L., Camp, R.A. and Coleman, K.M. (2004) The influence of party systems on citizens’ perceptions of corruption and electoral response in Latin America. Comparative Political Studies 37(6): 677–703.

Dimock, M. and Jacobson, G.C. (1995) Checks and choices: The House bank scandal’s impact on voters in 1992. The Journal of Politics 57(4): 1143–1159.

Dommett, K. and Flinders, M. (2014) The politics and management of public expectations: Gaps, vacuums, clouding and the 2012 mayoral referenda. British Politics 9(1): 29–50.

Fay, C. (1995) Political sleaze in France: Forms and issues. Parliamentary Affairs 48(4): 663–676.

Flinders, M. (2012) Defending Politics: Why Democracy Matters in the Twenty-First Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Flinders, M. (2016) The problem with democracy. Parliamentary Affairs 69(1): 181–203.

Flinders, M. and Dommett, K. (2013) Gap analysis: Participatory democracy, public expectations and community assemblies in Sheffield. Local Government Studies 39(4): 488–513.

Flinders, M. and Kelso, A. (2011) Mind the gap: Political analysis, public expectations and the parliamentary decline thesis. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 13(2): 249–268.

Gibbs, J.C. and Schnell, S.V. (1985) Moral development “versus” socialization: A critique. American Psychologist 40(1): 1071–1080.

Grødeland, Å.B., Miller, W.L. and Koshechkina, T.Y. (2000) The ethnic dimension to bureaucratic encounters in postcommunist Europe: Perceptions and experience. Nations and Nationalism 6(1): 43–66.

Hampshire, S. (ed.) (1978) Public and Private Morality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hay, C. (2007) Why We Hate Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Heath, O. (2011) The great divide: Voters, parties, MPs and expenses. In: N. Allen and J. Bartle (eds.) Britain at the Polls 2010. London: Sage, pp. 129–146.

Heidenheimer, A. (1970) The context of analysis: Introduction. In: A. Heidenheimer (ed.) Political Corruption: Readings in Comparative Analysis. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc, pp. 3–28.

Jackson, M. and Smith, R. (1996) Inside moves and outside views: An Australian case study of elite and public perceptions of political corruption. Governance 9(1): 23–41.

James, O. (2009) Evaluating the expectations disconfirmation and expectations anchoring approaches to citizen satisfaction with local public services. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 19(1): 107–123.

Johnston, M. (1986) Right and wrong in American politics: Popular conceptions of corruption. Polity 18(3): 367–391.

Johnston, M. (1991) Right and wrong in British politics: “Fits of morality” in comparative perspective. Polity 24(1): 1–25.

Jong-sung, Y. and Khagram, S. (2005) A comparative study of inequality and corruption. American Sociological Review 70(1): 136–157.

Kimball, D.C. and Patterson, S.C. (1997) Living up to expectations: Public attitudes toward Congress. The Journal of Politics 59(3): 701–728.

Klašnja, M., Tucker, J.A. and Deegan-Krause, K. (2016) Pocketbook vs. sociotropic corruption voting. British Journal of Political Science 46(1): 67–94.

Kohlberg, L. (1984) Essays in Moral Development, Vol. 2: The Psychology of Moral Development. San Francisco: Harper and Row.

Lacsoumes, P. (ed.) (2010) Favoritisme et Corruption à la Française: Petits Arrangements Avec la Probité. Paris: Presses Sciences Po.

Lavine, H. (2002) On-line versus memory-based process models of political evaluation. In: K.R. Monroe (ed.) Political Psychology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 225–247.

Lieberman, M.D., Schreiber, D. and Ochsner, K.N. (2003) Is political cognition like riding a bicycle? How cognitive neuroscience can inform research on political thinking. Political Psychology 24(4): 681–704.

Linde, J. and Erlingsson, G.Ó. (2013) The eroding effect of corruption on system support in Sweden. Governance 26(4): 585–603.

Lodge, M. and Taber, C.S. (2013) The Rationalizing Voter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mancuso, M., Atkinson, M.M., Blais, A., Greene, I. and Nevitte, N. (1998) A Question of Ethics: Canadians Speak Out. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Mayer, N. (2010) Entre morale et politique: une approche expérimentale des jugements sur la corruption. In: P. Lacsoumes (ed.) Favoritisme et Corruption à la Française: Petits Arrangements Avec la Probité. Paris: Presses Sciences Po, pp. 125–138.

McAllister, I. (2000) Kee** them honest: Public and elite perceptions of ethical conduct among Australian legislators. Political Studies 48(1): 22–37.

McCurley, C. and Mondak, J.J. (1995) Inspected by #1184063113: The influence of incumbents’ competence and integrity in US House elections. American Journal of Political Science 39(4): 864–885.

McManus-Czubińska, C., Miller, W.L., Markowski, R. and Wasilewski, J. (2004) Why is corruption in Poland “a serious cause for concern”? Crime, Law and Social Change 41(2): 107–132.

Mény, Y. (1996) Corruption French style. In: W. Little and E. Posada-Carbó (eds.) Political corruption in Europe and Latin America. London: Macmillan, pp. 159–172.

Mondak, J.J. (1995) Competence, integrity, and the electoral success of congressional incumbents. The Journal of Politics 57(4): 1043–1069.

Muxel, A. (2010) Familles politiques et jugements sur la probité. In: P. Lacsoumes (ed.) Favoritisme et Corruption à la Française: Petits Arrangements Avec la Probité. Paris: Presses Sciences Po, pp. 169–186.

Naurin, E. (2011) Election Promises, Party Behaviour and Voter Perceptions. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Naurin, E. (2014) Is a promise a promise? Election pledge fulfilment in comparative perspective using Sweden as an example. West European Politics 37(5): 1046–1064.

Norris, P. (ed.) (1999) Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Norris, P. (2011) Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pharr, S.J. and Putnam, R.D. (eds.) (2000) Disaffected Democracies: What’s Troubling the Trilateral Countries?. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Redlawsk, D.P. and McCann, J. (2005) Popular interpretations of ‘corruption’ and their partisan consequences. Political Behavior 27(3): 261–283.

Riddell, P. (2011) In Defence of Politicians (In Spite of Themselves). London: Biteback.

Royed, T.J. (1996) Testing the mandate model in Britain and the United States: Evidence from the Reagan and Thatcher eras. British Journal of Political Science 26(1): 45–80.

Runciman, D. (2008) Political Hypocrisy: The Mask of Power, from Hobbes to Orwell and Beyond. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Runciman, D. (2013) The Confidence Trap: A History of Democracy in Crisis from World War I to the Present. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rundquist, B.S., Strom, G. and Peters, J.G. (1977) Corrupt politicians and their electoral support: Some experimental observations. American Political Science Review 71(3): 954–963.

Saalfeld, T. (2000) Court and parties: Evolution and problems of political funding in Germany. In: R. Williams (ed.) Party Finance and Political Corruption in Europe. Basingstoke: Macmillan, pp. 89–122.

Sanders, D., Clarke, H.D., Stewart, M.C. and Whiteley, P. (2007) Does mode matter for modeling political choice? Evidence from the 2005 British election study. Political Analysis 15(3): 257–285.

Scarrow, S.E. (2003) Party finance scandals and their consequences in the 2002 election: Paying for mistakes? German Politics & Society 21(1): 119–137.

Seibel, W. (1997) Corruption in the Federal Republic of Germany before and in the wake of reunification. In: D. della Porta and Y. Mény (eds.) Democracy and Corruption in Europe. London: Pinter, pp. 85–102.

Seyd, B. (2015) How do citizens evaluate public officials? The role of performance and expectations on political trust. Political Studies 63(S1): 73–90.

Slomczynski, K. and Shabad, G. (2011) Perceptions of political party corruption and voting behaviour in Poland. Party Politics 18(6): 897–917.

Sniderman, P.M. (1975) Personality and Democratic Politics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Stoker, G. (2006) Why Politics Matters: Making Democracy Work. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Thompson, D.F. (1987) Political Ethics and Public Office. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Thompson, D.F. (1995) Ethics in Congress: From Individual to Institutional Corruption. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Torcal, M. and Montero, J.R. (eds.) (2006) Political Disaffection in Contemporary Democracies: Social Capital, Institutions, and Politics. Abingdon: Routledge.

Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D. (1974) Judgement under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science 185(4157): 1124–1131.

Twyman, J. (2008) Getting it right: YouGov and online survey research in Britain. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 18(4): 343–354.

Vivyan, N., Wagner, M. and Tarlov, J. (2012) Representative misconduct, voter perceptions and accountability: Evidence from the 2009 House of Commons expenses scandal. Electoral Studies 31(4): 750–763.

Wagner, M., Tarlov, J. and Vivyan, N. (2014) Partisan bias in opinion formation on episodes of political controversy: Evidence from Great Britain. Political Studies 62(1): 136–158.

Walzer, M. (1973) Political action: The problem of dirty hands. Philosophy & Public Affairs 2(2): 160–180.

Warren, M.E. (2004) What does corruption mean in a democracy? American Journal of Political Science 48(3): 328–343.

Winters, M.S. and Weitz-Shapiro, R. (2013) Lacking information or condoning corruption: When do voters support corrupt politicians? Comparative Politics 45(4): 418–436.

Zaller, J.R. (1998) Monica Lewinsky’s contribution to political science. PS: Political Science & Politics 31(2): 182–189.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the ESRC (Grant Number RES-000-22-3459) and British Academy (Grant Numbers SG-101785 and SG-52322). They would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

The data employed here were collected as part of the British, German and French Cooperative Campaign Analysis Projects (BCCAP, DECCAP and FRCCAP respectively) led by Ray Duch at Nuffield College, Oxford.

BCCAP was a multi-wave panel study carried out over the internet with participants drawn from the adult British population in collaboration with YouGov. A baseline survey was fielded in December of 2008, with subsequent panel waves taking place at 6-month intervals. Most of the data in this paper come from the third wave, fielded in September 2009, although the personal ethics questions were asked of respondents in the April 2009 wave. The number of respondents who took part in both waves was 809.

DECCAP was also a multi-wave panel study carried out over the internet with participants drawn from the adult German population in collaboration with YouGovPsychonomics. A baseline survey was fielded in June of 2009. Three subsequent waves took place, with the questions in this paper being fielded in the third wave in September 2009 before the Federal election. The respondents numbered 2341 in total. All the survey items were translated by native speakers and checked, via back-translation, by the researchers.

FRCCAP was a single survey administered online in January 2013. Respondents were recruited by Survey Sampling International (SSI) using a sample frame based on quotas for gender, age, education and region of residence. SSI rewards respondents in points, based on how long the survey takes, which they can then convert to vouchers of their choice. Respondents selected for the survey received non-specific email invites and were then redirected to a webpage administered by the Nuffield Centre for Experimental Social Sciences. The achieved sample was 1073. All the survey items were translated by native speakers and checked, via back-translation, by the researchers.

Dependent Variables

NB The variable names are in bold. All questions are provide in English.

Honesty over delivery This variable was constructed by reversing responses, still using a 0–10 scale, to the following question:

People want competent and honest politicians, but they disagree over which trait is more important. Some people say that it is more important to have politicians who can deliver the goods for people, even if they aren’t always very honest and trustworthy. Other people say that it’s more important to have politicians who are very honest and trustworthy, even if they can’t always deliver the goods. What do you think? Using the 0–10 scale below, where 0 means it’s more important to have politicians who can deliver the goods and 10 means it’s more important to have very honest and trustworthy politicians, where would you place yourself?

10 = most willing to compromise on honesty

0 = not at all willing to compromise on honesty.

Accepting bribes, abusing expenses, empty promises and straight answers These variables were based on responses to the following questions:

How much of a problem is the following behaviour by elected politicians in [Britain/France/Germany] today? Please use the 0–10 scale, where 0 mean it is not a problem at all and 10 means it is a very big problem.… [Not giving straight answers to questions] [Accepting bribes] [Misusing official expenses and allowances] [Making promises they know they can’t keep].

10 = it is a very big problem

0 = it is a not a big problem.

Independent Variables

Age Age in years.

Gender (male) coded 0 = female, 1 = male.

Income The BCCAP asked the following question: ‘What is your gross household income?’ The FRCCAP and DECCAP asked respondents to indicate their monthly net income. The BCCAP income measure was a 1–15 scale ranging from ‘under £5000 per year’ to ‘£150,000 per year and over’; the FRCCAP income measure was a 1–11 scale ranging from ‘less than €300 per month’ to ‘€8001 per month or more’; and the DECCAP income measure was a 1–8 scale ranging from ‘less than €1000 per month’ to ‘more than €4000 per month’. Comparable dummy variables were constructed from these scales:

Income: lower band (1 = less than £15,000 per year [gross] OR €1000 per month [net]).

Income: middle (1 = £15,000–£49,999 per year [gross] OR €1000–€3000 per month [net]).

Income: upper band (1 = more than £50,000 per year [gross] OR €3000 per month [net]).

Tertiary education coded 0 = non-graduate, 1 = graduate.

Party identification The BCCAP, FRCCAP and DECCAP fielded a standard question about partisanship, e.g. ‘Generally speaking do you think of yourself as Labour, Conservative, Liberal Democrat or what?’ Responses to these questions were used to create simple dummy variables, where 0 = no and 1 = yes, for the following objects of identification:

Centre-right parties: British Conservative Party; French Union for a Popular Movement; German Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union of Bavaria.

Governing parties: British Labour Party; French Union for a Popular Movement; German Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union of Bavaria and Social Democratic Party.

Opposition parties: British Conservative Party, Liberal Democrats and others; French Socialist Party, National Front and others; German Free Democrats, Greens, The Left and others.

No party identification: none.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Allen, N., Birch, S. & Sarmiento-Mirwaldt, K. Honesty above all else? Expectations and perceptions of political conduct in three established democracies. Comp Eur Polit 16, 511–534 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-016-0084-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-016-0084-4