Abstract

Objectives:

To assess the influence of financial constraints on access to different components of spinal cord injury (SCI) management in various socio-economic strata of the Indian population.

Setting:

Indian Spinal Injuries Centre (ISIC).

Methods:

One hundred fifty SCI individuals who came for follow-up at ISIC between March 2009 and March 2013 with at least 1 year of community exposure after discharge were included in the study. Socio-economic classification was carried out according to the Kuppuswamy scale, a standard scale for the Indian population. A self-designed questionnaire was administered.

Results:

No sample was available from the lower group. There was a statistically significant difference (P<0.05) for the levels of difficulty perceived by different socio-economic groups in accessing different components of SCI management. Aided upper lower group was dependent on welfare schemes for in-hospital treatment but could not access other components of management once discharged. Unaided upper lower group either faced severe difficulty or could not access management. Majority of lower middle group faced severe difficulty. Upper middle group was equally divided into facing severe, moderate or no difficulty. Most patients in the upper group faced no difficulty, whereas some faced moderate and a small number of severe difficulty.

Conclusion:

Financial constraints affected all components of SCI management in all except the upper group. The results of the survey suggest that a very large percentage of the Indian population would find it difficult to access comprehensive SCI management and advocate extension of essential medical coverage to unaided upper lower, lower middle and upper middle groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a devastating ailment that poses a tremendous financial burden on the individual, the family and the society.1, 2 Substantial costs are incurred throughout the life of a person with SCI and include initial costs of hospitalization, acute rehabilitation, home and vehicle modifications, and recurring costs for medical equipment, medications and personal assistance.3

The influence of economic status on access to health services is well established.4 However, social barriers are equally important in care access, especially in develo** countries and therefore socio-economic rather than just economic status may better reflect the ease of access to health services.5 This becomes all the more relevant for an ailment like SCI because of the prolonged treatment and the high expenses involved. If there is inadequate financial cover, then it makes the treatment of this detrimental injury extremely challenging for a considerable percentage of people sustaining SCI.6

Like in other emerging countries, the scenario in India is more challenging. Comparing with the global economy, the average Indian GDP per capita of $4000 (2013 estimated) is much lower than the average global GDP of $13 100 (2013 est.) 7 The World Bank reported that a third of the total Indian population (32.7%) falls below the international poverty line of US$ 1.25 per day (Purchasing Power Parity), whereas two-thirds (68.7%) live on less than US$ 2 per day.8 Moreover, the public spending on health has remained low,9 health insurance coverage has been reported to be only 10% in urban areas4 and the private out-of-pocket expenditures on health are among the highest in the world (74.4% in 2008 as per the World Health Statistics 2011).10

The financial factor leading to non-treatment of ailments in India has doubled.11 The situation seems to be grimmer in the rural areas. Borrowing or sale of assets, ornaments and draught animals was observed to be double in the rural hospitalized cases as compared with the urban ones.11

The socio-economic scenario in India thus poses a big challenge to SCI management. A previous study conducted by the senior author in the same centre to study the causes of neglected traumatic SCI revealed that financial constraints were the second most common cause of neglect.12 Another study in a rural community in India revealed that financial problems were the major barrier for neurological rehabilitation.13

Although studies have been conducted to assess the influence of socio-economic status on the accessibility to medical care14 in India, there is no study specific to people with SCI. We thus conducted this study to assess how financial constraints in various socio-economic strata of the Indian population influence access to different components of SCI management.

Materials and Methods

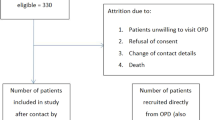

The study was approved by the Institutional Research Review and Ethics Committees. Using convenience sampling, we included all male SCI individuals who came for follow-up at Indian Spinal Injuries Centre (ISIC) between March 2009 and March 2013 with at least 1 year of community exposure after discharge from ISIC. They had been through all aspects of initial hospitalization, rehabilitation, purchase of devices, home modifications and community inclusion.

After obtaining informed consent from the participants, we used a specifically designed questionnaire (Table 1) to document levels of difficulty experienced by the subjects due to financial reasons for various components of management, with 17 questions related to access to health care, acute care, surgical intervention, the rehabilitation process, purchase of aids and equipment, home modification and recreational activities. The questionnaire was developed based on our experience of difficulties faced by spinal-injured individuals to access SCI management due to financial reasons.

We used Kuppuswamy’s socio-economic scale (2012) (Table 2) to divide the sample population into five groups (lower, upper lower, lower middle, upper middle and upper).15

‘Poverty Line’ is an economic benchmark and poverty threshold used by the government of India to indicate economic disadvantage. Individuals/households who earn less than the threshold qualify for government assistance and aid. Subjects who were ‘below poverty line (BPL)’ and hence fully covered by the hospital welfare scheme for their hospital stay, investigations, treatment, rehabilitation and wheel chair were segregated in a separate group.

The level of difficulties faced by the subjects due to financial constraints for accessing various components of SCI management was documented as ‘No difficulty, Moderate difficulty, Severe difficulty and Could not access.’ The difficulties faced by the study participants were analyzed using chi-squares test across different categories for each question separately. Categorical demographic variables and Community Integration Questionnaire (CIQ) scores were tested between subgroups using the chi-squares test and continuous variables were tested using one-way ANOVA with Tukey Kramer post hoc analysis for pair-wise comparisons.

Results

One hundred fifty SCI individuals were included in the study. There were no individuals from the lower socio-economic group in the study. All patients falling BPL receive free treatment at ISIC and their socio-economic status is worked out by the social worker. We confirmed from their records that no individuals from the lower socio-economic group were admitted in ISIC in this period.

Demographics and CIQ scores of the study participants are depicted in Table 3.

The CIQ scores were significantly higher (P<0.05) for the upper middle (15) and upper groups (12.5) in comparison with the BPL, upper lower and lower middle groups (~8).

Subjective interpretation of the response to the questionnaire by spinal-injured individuals of each Kuppuswamy socio-economic group is depicted in Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Chi-square tests within socio-economic groups show a significant difference (P<0.05) in the degree of difficulty reported for each question.

The subjects in the aided upper lower group who fell under BPL category were funded for the inpatient management by the hospital’s welfare scheme. They could not avail the pre- and post-hospital component of SCI management. Severe difficulties due to financial constraints were reported by the unaided upper lower, lower middle and most of the upper middle group. Some subjects of the upper middle group also reported moderate difficulties. The subjects of the upper group were the only ones who reported no difficulty in availing most aspects of management.

Discussion

Easy access to a comprehensive spinal injury center and all components of SCI management are important for any spinal-injured individual as outcomes are better if management is initiated early, especially in an organized multidisciplinary SCI care system16 and a lifelong follow-up is required. In emerging countries like India, spinal cord injured face major challenges in accessing all components of SCI management, not only because of inadequate services and infrastructure but also because of financial constraints.2, 17, 18 Hence, we tried to assess the influence of financial constraints on access to different components of SCI management in the Indian population in this study. As far as we are aware, this is the first such study in the Indian population.

This study suggests that socio-economic factors could be one of the main roadblocks for SCI management in a less developed country like India. This is expected as SCI is among the most expensive as compared with that of any other ailment.19 Majority of the expenditure is incurred in the first year after injury. The mean expense in this regard has been reported to be $16 911 in 2013.20 Subsequently, average annual costs of SCI management vary from $28 334 for cervical complete to $16 792 for thoracic incomplete SCI.21 The consolidated life time costs caused because of SCI depend on the severity of the injury and the age of the injured. The published figures in 2013 vary between $1 092 521 and $4 633 137.20 In India, the challenge gets compounded, as the average GDP per capita is much lower than the average global GDP, the public spending on health is low9 and health insurance coverage has been reported to be only 10% in urban areas.4 Therefore, the spinal injured’s household has to bear most part of the financial burden.22 Although progressive legislation, schemes and provisions exist for people with disability in India, persons with disability continue to be neglected and marginalized at the ground level.23

Socio-economic rather than just economic status is a better reflection of the ease of access of health services.5 Socio-economic stratification is the key to understand affordability of health services and amenities.24 Hence, we studied how financial constraints influence access to different components of SCI management in various socio-economic strata of the Indian population. For socio-economic stratification, we used Kuppuswamy's scale, the most widely used scale for hospital and community-based research in India. It was devised by Kuppuswamy in 1976 and is updated periodically according to the level of education, occupation and economy of the Indian population.25 It divides the study population into five groups (lower, upper lower, lower middle, upper middle and upper) based on the cumulative score of education of the head of the family, occupation and family income per month.

Only males were included in the study in order to have a homogenous cohort. No recruitment of subjects from the lower group in this study may suggest that this section of the society do not even have the resources to reach a tertiary level center. The unaided upper lower, lower middle and upper middle groups find it very difficult to manage the financial aspect of the burden of SCI in the acute stage. Sixty-five percent of the upper lower group (BPL group) got most components of the treatment free from the hospital welfare scheme but could not meet the expenses on the rest. Only the upper group was found to be self-sufficient in availing most components of treatment without any grants.

Other studies have similarly identified that cost is a significant barrier in availing treatment for SCI, which further hinders the physical fitness and thus compromises independent living.2, 13, 17, 18The findings of the survey by Samuel Kamalesh Kumar et al.26 showed low levels of community integration in rehabilitated south Indian persons with SCI due to financial constraints despite their having achieved physical independence.

A study of 59 countries found lack of health insurance to be one of the main factors for health expenditure being nearly 40% of all household expenditure.22 The responsibility of health financing in most of the less and least developed countries is thus catered for by the individuals themselves by means of out-of-pocket expenditure.22 This holds true for serious illnesses like spinal injuries as well, leading to drastic financial imbalances. Relyea-Chew et al.27 estimated the prevalence of medical debt among traumatic brain injury and SCI patients who discharged their debts through bankruptcy. They concluded that 5% of randomly selected petitioners and 26% of petitioners with traumatic brain injury or SCI had substantial medical debt. SCI and traumatic brain injury petitioners had fewer assets and were more likely to be receiving government income assistance at the time of bankruptcy than the controls.27 Lack of insurance cover was noted as a barrier to persons with SCI being active19 in less and least developed countries. As there is no mandatory lifelong government cover for injuries causing permanent impairment,21 the individuals with SCI and their families also bear the burden of lifelong ongoing costs. The findings of this as well as another study from Tehran17 point out to the importance of economic resource management in reducing the burden of SCI.

This study helps in a better understanding of how socio-economic status influences access to different components of SCI management and should thus help policy makers in planning for provision of services accordingly. The findings of our study, as well as those of the other mentioned studies, suggest that a large number of SCI patients, especially those from the lower and middle socio-economic strata, require financial support to access proper treatment. Essential medical coverage for SCI management should thus also be extended to the unaided upper lower, lower middle and upper middle Indian groups, as these strata face maximum financial challenges in all the stages of treatment.

The findings of our study also suggest that purely economic criteria for example BPL status may not be appropriate for determining the need for financial aid in SCI patients. As socio-economic stratification is the key to understand affordability,24 it could form the basis of provision of financial aid by the government.

The study had various limitations. First, a self-designed questionnaire was used because of a lack of a standardized measurement to determine the constraints faced. Second, psychometric analysis of the questionnaire was not performed. This introduces an intrinsic design flaw in reporting the level of difficulties. As perception is expressed through self-report, the individual may subconsciously use the intensity of difficulties as a justification for inhibiting personality or emotional factors. However, this was the only available means to quantify the difficulties faced by SCI patients. Third, other factors affecting the costs and hence the affordability of treatment like the duration since the injury, length of stay and the level of injury were not considered in the study. Fourth, this study is limited to a single center, which provides tertiary care for spinal ailments. A very small percentage of spinal-injured population is able to reach out to such centers because of various financial and social reasons. The perceptions of patients who are admitted in other government or private institutions could not be assessed. Future multicentre studies are recommended. Fifth, there were no individuals from lower socio-economic status in the study, as none were admitted at ISIC in this period. The non-availability of samples of the lower group suggests that this survey would be more appropriate if conducted with a door-to-door interview. Such a survey can also better assess the problems of social inclusion but may not be practical because of the distances and expenditure involved and the time consumed. Finally, we could not also analyze the socio-economic status wise return rate of patients, as we do not record socio-economic status of all patients seeking inpatient treatment at ISIC.

Conclusions

Financial constraints affected all components of treatment in all groups except the upper group. Thus, it is expected that a very large percentage of the Indian population would find it difficult to access the expenses of SCI management and community integration. The subjects of the lower group are often not even able to reach a tertiary level center. The results of the survey advocate extension of essential medical coverage for SCI management to the unaided upper lower, lower middle and upper middle socio-economic Indian groups, as these strata face maximum financial challenges in all the stages of treatment. It also suggests that socio-economic rather than just the financial criteria should form the basis of medical aid by the government.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Berkowitz M, O’Leary PK, Kruse DL, Harvey C . Spinal Cord Injury: An Analysis of Medical and Social Costs. Demos Medical Publishing: New York. 1998.

Rahimi-Movaghar V . Efficacy of surgical decompression in the setting of complete thoracic spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2005; 28: 415–420.

Priebe MM, Chiodo AE, Scelza WM, Kirshblum SC, Wuermser L-A, Ho CH . Spinal cord injury medicine. 6. Economic and societal issues in spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88: S84–S88.

Kumar GA, Dilip TR, Dandona L, Dandona R . Burden of out-of-pocket expenditure for road traffic injuries in urban India. BMC Health Serv Res 2012; 12: 285.

Bairwa M, Rajput M, Sachdeva S . Modified Kuppuswamy’s socioeconomic scale: social researcher should include updated income criteria, 2012. Indian J Commun Med 2013; 38: 184–185.

Lloyd EE, Baker F . An examination of variables in spinal cord injury patients with pressure sores. SCI Nurs 1986; 3: 19–22.

The World Factbook. 2004. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2004.html (accessed 6 February 2015).

Global Poverty Estimates. World Bank 2012. http://povertydata.worldbank.org/poverty/country/IND (accessed 6 February 2015).

Prinja S, Bahuguna P, Pinto AD, Sharma A, Bharaj G, Kumar V et al. The cost of universal health care in India: a model based estimate. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e30362.

India Country Report 2013, Statistical Appraisal, Central Statistics Office. http://mospi.nic.in/mospi_new/upload/SAARC_Development_Goals_%20India_Country_Report_29aug13.pdf, 2013.

Select Health Parameters : A Comparative Analysis across the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) 42, 52 and 60 Rounds. Minist. Heal. Fam. Welfare, India 2007. http://www.prognosis2010.org/downloads.html (accessed 6 February 2015).

Chhabra HS, Arora M . Neglected traumatic spinal cord injuries: causes, consequences and outcomes in an Indian setting. Spinal Cord 2013; 51: 238–244.

Kumar H, Gupta N . Neurological disorders and barriers for neurological rehabilitation in rural areas in Uttar Pradesh: a cross-sectional study. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2012; 3: 12–16.

Raminashvili D, Gvanceladze T, Kajrishvili M, Zarnadze I, Zarnadze S . Social environment, bases social markers and health care system in Shida Kartli region. Georgian Med News 2009; 175: 68–70.

Sharma A, Gur R, Bhalla P . Kuppuswamy’s socioeconomic scale: updating income ranges for the year 2012. Indian J Public Health 2012; 56: 103–104.

DeVivo MJ, Kartus PL, Stover SL, Fine PR . Benefits of early admission to an organised spinal cord injury care system. Paraplegia 1990; 28: 545–555.

Rahimi-Movaghar V, Moradi-Lakeh M, Rasouli MR, Vaccaro AR . Burden of spinal cord injury in Tehran, Iran. Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 492–497.

Rimmer JH, Riley B, Wang E, Rauworth A, Jurkowski J . Physical activity participation among persons with disabilities barriers and facilitators. Am J Prev Med 2004; 26: 419–425.

Reducing Risks and Preventing Disease: Population-wide Interventions. Global Status Report On Noncommunicable Diseases 2010. World Health Organization, 2011. (http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd_report2010/en/).

National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems: 2013 Annual Report. https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/PublicDocuments/reports/pdf/2013%20NSCISC%20Annual%20Statistical%20Report%20Complete%20Public%20Version.pdf, 2013.

French DD, Campbell RR, Sabharwal S, Nelson AL, Palacios PA, Gavin-Dreschnack D . Health care costs for patients with chronic spinal cord injury in the Veterans Health Administration. J Spinal Cord Med 2007; 30: 477–481.

Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, Murray CJL . Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet 2003; 362: 111–117.

Lal R . Disabilities: Background & Perspective. Infochange Disabil http://infochangeindia.org/disabilities/backgrounder/disabilities-background-a-perspective.html (accessed 6 February 2015).

Kumar BR, Dudala SR, Rao A . Kuppuswamy’s socio-economic status scale – a revision of economic parameter for 2012. Int J Res Dev Health 2013; 1: 2–4.

Sharma R, Saini NK . A critical appraisal of Kuppuswamy’s socioeconomic status scale in the present scenario. J Fam Med Prim Care 2014; 3: 3–4.

Samuelkamaleshkumar S, Radhika S, Cherian B, Elango A, Winrose W, Suhany BT et al. Community reintegration in rehabilitated South Indian persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010; 91: 1117–1121.

Relyea-chew A, Hollingworth W, Chan L, Comstock BA, Overstreet KA, Jarvik JG . Personal bankruptcy after traumatic brain or spinal cord injury : the role of medical debt. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009; 90: 413–419.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the help of Mr. Kulwant Singh (AIIMS) and Dr Vandana Phadke in the statistical analysis; we also acknowledge the help of Dr Vandana Phadke and Ms. Meenakshi Mohan in finalizing the text of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chhabra, H., Bhalla, A. Influence of socio-economic status on access to different components of SCI management across Indian population. Spinal Cord 53, 816–820 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.80

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.80

- Springer Nature Limited